Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

10 Meaningful Literary Moments That Were Lost In Translation

History’s greatest novelists include Tolstoy, Kafka, and Proust, and though none of them wrote in English, their books do a roaring trade across the English-speaking world. But not all aspects of their writing are easily translatable. Some of the best-known works of literature have moments that we English speakers are completely missing out on.

10In Search Of Lost Time’s Opening

Writing a great opening line is a skill all by itself. Sentences like “Call me Ishmael” and “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” are almost as famous as the novels that contain them. The opening line of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, on the other hand, isn’t. In English, it simply reads: “For a long time I used to go to bed early.”

That’s not an especially striking way to start a 1.5-million-word text that’s meant to be one of the greatest ever written. The problem is that the French is simply untranslatable.

The original opens with the words: “Longtemps, je me suis couche de bonne heure.” Unfortunately for those of us who don’t speak French, the tense it’s written in has no English equivalent. Proust’s original shows he’s talking about an action that took place in the past but has effects continuing up to the present. The English version simply tells us about a former habit of his.

Then there’s the word longtemps. For French readers, it has a slightly mythic quality, like starting a story with the phrase: “a long, long time ago . . . ” Finally, bonne heure sounds really similar to bonheur or “happiness.” So, French readers immediately have in mind old myths, notions of happiness, and the passage of time. By contrast, English readers have nothing but someone who hates staying up late.

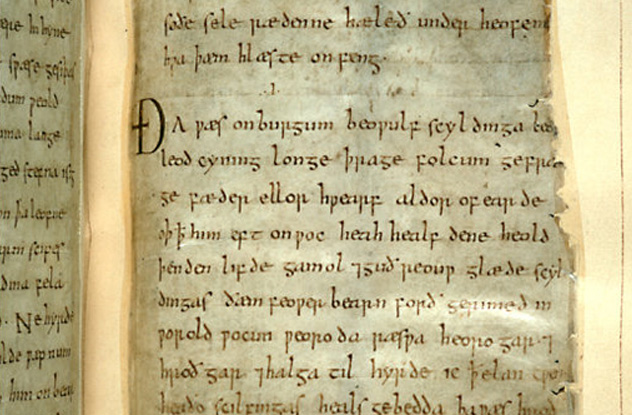

9Beowulf’s Characters Have Important Names

The first English epic, Beowulf is a sweeping story about Scandinavians facing off against hideous, nightmarish creatures. Written in Old English, it’s pretty much unreadable today unless you have a translation or a real hankering to learn a dead language. While it’s possible to preserve the poem’s rhythm in modern English, the same can’t be said for the characters’ names. In the original, they add a whole new level of meaning to the story.

The name “Beowulf” alone is significant. Literally, the name means “wolf of the bee “—a sentence that makes little sense until you realize “wolf” also means “foe.” “Bee-foe” was a northern European nickname for bears, thanks to their habit of raiding hives for honey. The name Beowulf is meant to conjure both images of wolves and bears, indicating that our hero is the manliest man in a book about some very manly men.

Other names give clues about characters or their eventual fates. One headstrong queen is literally called “power” (Thryth) while her sensible counterpart is named “reflection” (Hygd). There’s even a character called “glove” (Hondsico) who ends up in the monsters glof (lair), an accidental bit of foreshadowing that only works if you know both Old and modern English.

8The Guardian Of The Word‘s Accidental Rape Scene

Cultural differences impede translation as much as language does. One instance of this happens in Camara Laye’s Guardian of the Word. A collection of epic tales from Guinea hung together around a simple framework, the book features the story of Maghan Kon Fatta, whose wife Sogolon refuses to sleep with him. In response, Fatta threatens to slit her throat then seduces her at knifepoint. She then falls in love with him all over again.

For most English-speaking readers, there’s only one way to understand that scene: Fatta has just intimidated and violently raped Sogolon. Yet this doesn’t seem to be the reaction Laye had in mind. According to writer Ann Morgan, the scene is almost certainly meant to be interpreted from a symbolic standpoint. Rather than feel anger toward the character of Fatta, Guinean readers would see the scene as a ritualistic metaphor that ties in to the larger story.

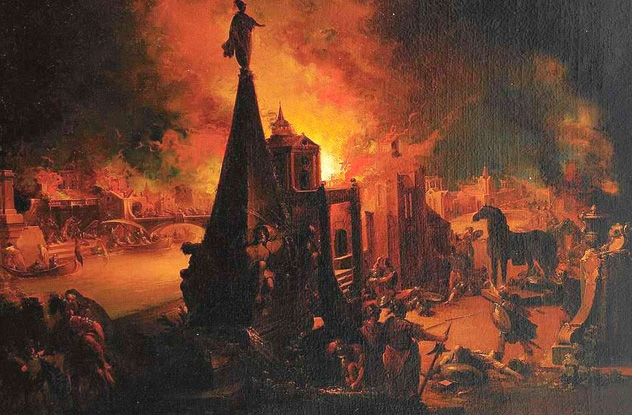

7The Rhythm Of The Iliad Evokes The Sea

The story of the Trojan War told through the eyes of a bunch of seafaring Greeks, the Iliad is today known as the earliest work of Western literature. The ocean plays a significant part in the tale, functioning as a physical entity and a source of metaphors. It also influenced the poem’s composition. In the original Greek, reading certain passages out loud is intended to evoke the rhythm of the sea.

In lines 795–800 of Book 13, the last words of the first, third, fifth, and sixth lines all end with what the New Yorker calls “liquid ‘l’ sounds.” These sounds are meant to conjure up images of rolling waves, while a repeated “p-ll” sound pattern represents the surf breaking onto the beach. Additionally, two adjectives in the fourth line duplicate each other’s consonants in such a way as to duplicate the real-life sound of surf. Even more elaborately, the last two lines repeat features of one another to symbolize the rows of Trojan soldiers about to stamp out onto the beach.

This is awe-inspiring stuff, and it’s almost impossible to accurately translate. While English can reproduce some of these sounds, combining them with words that both convey the meaning and duplicate Homeric touches like alliteration is a fool’s game. Unless you’ve got the time to learn Ancient Greek, you’ll always be missing part of the Iliad’s magic.

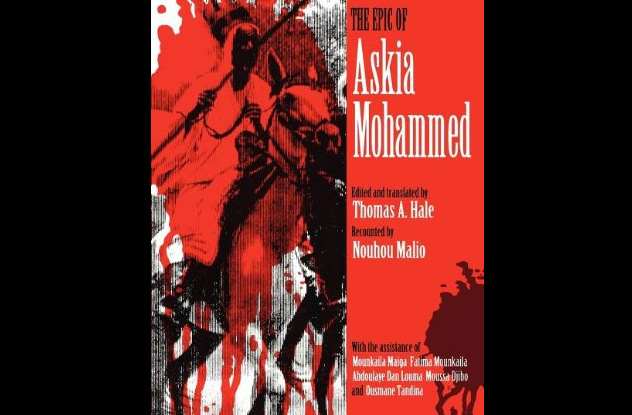

6The Epic Of Askia Mohammed Doesn’t Work On Paper

In the early 1980s, researchers translated one of Niger’s greatest oral epics into English. Hiring a local griot (storyteller) for two evenings in the village of Saga, they recorded him speaking then spent 10 years transcribing his story onto paper. The result was The Epic of Askia Mohammed, an important contribution to the ranks of Nigerien culture. Sadly, if you want to experience this epic in all its glory, you’re going to have to hire a griot and learn the local lingo, because the Epic simply doesn’t work on paper.

For starters, the use of sound is vitally important to Nigerien griots’ tales. With many words in their stories being unfamiliar to listeners, the griots instead make the sound and rhythm of their tale more important than the actual content. The tales themselves are also so utterly fluid that transcribing a definitive version into English is impossible. According to Thomas Hale, who led the team that recorded the Epic, griots have multiple versions of every tale and frequently tailor them to better suit Western researchers.

The written Epic of Askia Mohammed is simply a shadow of the real tale, which is impossible for anyone outside Niger to ever experience.

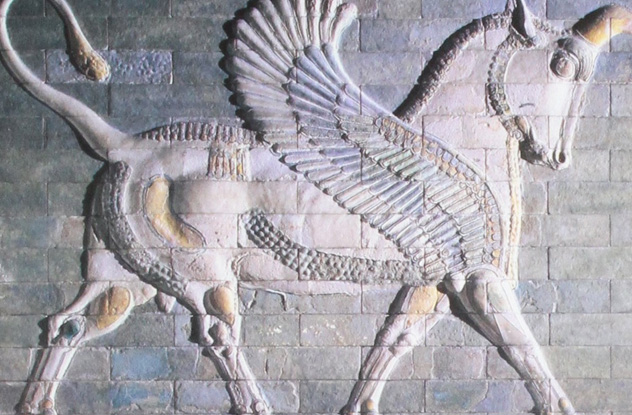

5Gilgamesh’s First Line Has Layers Of Meaning

Discovered underneath Iraq’s burning desert over 2,000 years after it was initially written, the Epic of Gilgamesh is one of literature’s first masterpieces. Although two separate versions are now known to exist, the most famous one (known as the Standard Version) opens with the line: “He who saw the deep.” Poetic as that is, it’s only a fraction of what the words signify in the original standard Babylonian.

Gilgamesh is the tale of a mighty king who goes searching for immortality and instead comes to terms with his eventual demise. As a result, the word “deep” takes on many meanings. Depending on the translator, it can be rendered as “he who saw everything,” “he who saw the abyss” (i.e., death), or “he who saw Ea “—a hidden cosmic realm sort of similar to the concept of hell. It can even be read as Gilgamesh gaining a higher spiritual understanding of the universe or as foreshadowing the moment in the poem when Gilgamesh dives down into a sacred subterranean sea.

Thanks to the difficulties in rendering standard Babylonian into English, exactly what the author meant is a topic that still inspires ferocious debate. Everyone agrees, though, that the line’s full significance is lost in translation.

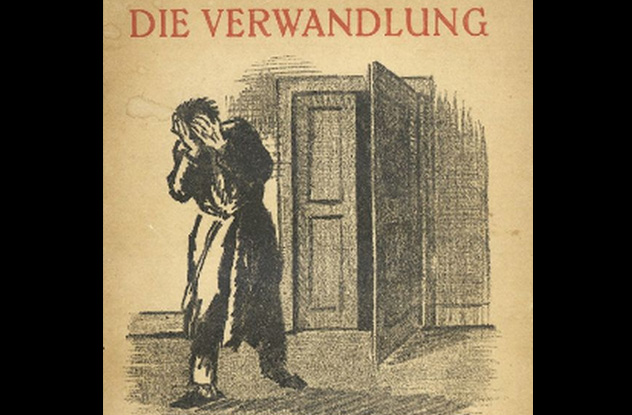

4Kafka’s Metamorphosis Is About More Than Just A Bug

A 1915 story about a man, Gregor Samsa, who wakes up to discover he’s turned into a bug, Kafka’s Metamorphosis is one of the most famous novels ever written. The concept has inspired everything from Oscar-winning films to Simpsons spoofs. Yet nearly all of them miss out one important aspect. In the original German, the term Kafka used, Ungeziefer, means more than just a bug.

Firstly, it doesn’t refer solely to insects. Ungeziefer can be used in relation to any sort of household pest, whether it has six legs or only four. The word also has an important lineage: In Middle High German, it literally meant “creature unfit for sacrifice.” But perhaps the most significant thing Ungeziefer implies can’t be rendered in English at all. According to Slate, “Ungeziefer is a necessarily vague word for something repulsive and unwelcome in the house, whose repulsiveness is defined through the eyes of its human beholder.”

The first line can be read as Gregor Samsa waking up to discover other people now regard him as no better than a cockroach. This allows readers to see the tale as anything from a metaphor for terminal illness to Kafka reflecting on his Jewish identity in an age when Jews were viewed as little more than vermin.

3Faithful Translations Of War And Peace Are Unreadable

Most translators try their best to keep both the meaning and the rhythm of an author’s words when putting them in English. With a book like War and Peace, however, this is almost impossible. A faithful English version of Tolstoy’s masterpiece would contain so much repetition that most readers would simply give up.

For Russian readers, the repeated use of adjectives is one of the book’s most significant traits. One famous bit describing a fat peasant uses the word “round” five times in a single sentence. Another uses the word “wept” six times in as many lines. These aren’t just isolated incidents. War and Peace is so stuffed with repeating words that Nabokov felt they were the key to understanding Tolstoy’s philosophy. For English readers, though, any attempt to replicate this structure tends to drag us right out of the narrative. While reading the word “round” over and over in Russian might be poetic, in English, it’s more likely to be alienating.

Another problem comes from Tolstoy’s love of languages. The first paragraph of War and Peace was originally written in French, and overall, the book contains enough French passages to fill a small novel. There are also sections in Italian, German, and even English, with Tolstoy often switching languages mid-sentence. Since preserving this aspect of the book would limit its potential audience to polyglots and academics, most translators simply don’t bother.

2The Gospel Of St John’s Key Moment Only Works In Greek

In a book full of iconic moments, one part of the Gospel of John stands out above all others: the moment when Jesus asks Peter three times if he loves Him. It’s a key moment in our understanding of Peter’s relationship to Christ. Unfortunately, it only works in the original Greek.

Unlike modern English, ancient Greek had multiple words for expressing love. Greeks could express their feelings using Eros (sexual love), Philia (friendship), or Agape (selfless love). In the Gospel of John, Jesus very specifically asks Peter twice if he loves Him using the term Agape (“do you selflessly love Me?”) Peter, who later denies knowing Jesus, can only respond with Philia (“I love You as a friend“).

The choice of words becomes even more important when Jesus asks Peter the third time. Instead of saying “Agape” again, He switches to “Philia,” coming down to Peter’s level. This explains why Peter gets recoils at being asked the third time. By throwing his words back at him, Jesus is showing Peter the limitations of his devotion. For the Gospels’ original readers, this would be an absolutely pivotal scene. In English, it simply seems like the Son of God is hard of hearing.

1Finnegans Wake Sends Its Translators Mad

The final novel by James Joyce, Finnegans Wake is either the best thing ever written or an incomprehensible mess, depending on whom you ask. Although technically in English, it’s nearly incomprehensible. Here’s a typical line:

The fall (bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonneronntuonn-thunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurnuk!) of a once wallstrait oldparr is retaled early in bed and later on life down through all christian minstrelsy.

Editor’s note: We had to add that hyphen to the super-long word up there just so it would be visible. The original does not include that hyphen.

Although it looks like nonsense, that extract is stuffed with allusions. For example, the cluster of letters “gharaghtak” in that super-long word references the Hindustani term for thunder, plus a separate word meaning “boisterous.” The word “wallstrait” refers to both Wall Street and being in dire straits (i.e., in crisis) so functions as a reference to the Wall Street Crash. The challenge of getting these double and triple meanings across in a different language frequently drives translators mad.

We don’t mean that figuratively. Dai Congrong spent eight years translating the first third of the Wake into Chinese. By her own account, she suffered so much that her body wasted away. The French version ate up 30 years of its translator’s life, while the Japanese version had its first translator disappear and the second go clinically insane. Even the relatively untroubled Polish version took a decade and ended with its translator angrily declaring it a waste of time and the source of countless domestic quarrels. Perhaps it’s no surprise it originally took Joyce 14 years to write the thing.