History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Nazi War Criminals Who May Escape Justice Forever

As time ticks onward, the atrocities committed in Nazi Germany are fading from living memory and into the pages of history books. Those who survived the Third Reich, the concentration camps, and Hitler’s mad regime are dying—and that means our hunt for the remaining free Nazi war criminals is coming to an end. Men responsible for some of the most heinous acts in recent history are dying free, and our time to bring them to justice is growing increasingly limited.

In March 2015, Soren Kam, the fifth most wanted Nazi war criminal named by the Simon Wiesenthal Center, died free. A member of the SS-Viking division, Kam had already been found guilty of killing a Danish newspaper editor. He fled to Germany, though, getting citizenship and dodging all attempts to return him to Denmark to answer for the crime that his associates had already been executed for.

Those seeking justice are making some unprecedented attempts to make sure that at least something is served.

10John Demjanjuk

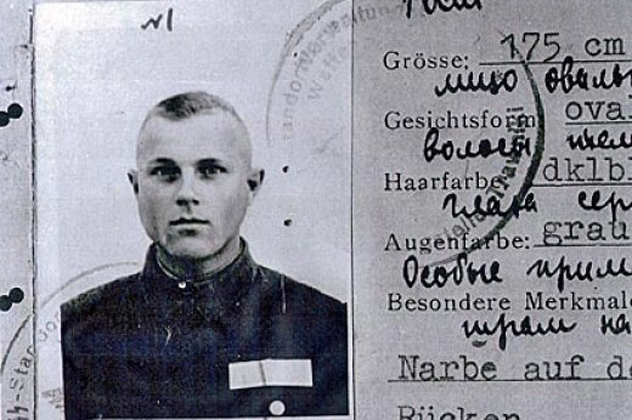

It’s only fairly recently that the last, final push to bring the remaining Nazi war criminals to some sort of justice began, and it was largely because of the verdict in the case of John Demjanjuk.

We’ve talked about the mystery behind just who he was and what he was responsible for, where the courts were arguing about whether or not they had the right man. Ultimately, Demjanjuk was convicted of being an accessory to the murder of more than 28,000 people in the Sobibor concentration camp in Poland. The courts declared that there was enough evidence—including an ID card—to indicate that he had been a guard at the came between March and September 1943. The 28,000 people had been killed at the camp while he was there.

His conviction set an incredible precedent for prosecutions to follow. Demjanjuk’s case was the first where courts found a person guilty in spite of no direct links or evidence between the accused and a specific crime. There was nothing that ever indicated he was an active participant in murder, but prosecutors in Germany argued that his role as a guard in a camp where the only purpose was murder was enough to convict him of accessory.

Suddenly, that also meant that there was a precedent for pursuing others, especially those who had been stationed at the Nazis’ death camps. After this case, wearing the uniform and being at the camp was enough to make a person guilty. This also overturned an earlier precedent, set in 1976, when SS commandant Karl Streibel was acquitted of war crimes when it was argued that he didn’t know what he was training soldiers to do.

9Heinrich Boere

In March 2010, 88-year-old Henrich Boere was handed a life sentence for three murders committed while he was an SS officer in the Netherlands.

According to Boere, he did commit the murders that he was accused of, but he was acting under the orders of his superior officers when he shot and killed chemist Fritz Bicknese, Dutch resistance member Frans Kusters, and Teun de Groot, a bicycle seller who had been aiding Aachen Jews. Boere stated that he had been ordered to kill all three for their activities in the resistance, but the prosecution was able to convince the court that the murders were completely random and carried out against civilians who were absolutely no threat to any of the SS officers.

The three men were killed in 1944, and justice has been an incredibly long time in coming. Boere was captured and held after the end of the war, when he admitted his involvement. He escaped, though, and fled to Germany, where repeated attempts to extradite him failed in the face of a debate over his citizenship. In 1949, he was sentenced to death for the crimes—a sentence later reduced to life in prison—but it wasn’t until 2008 that he was indicted. For a time, it looked as though he was going to get out of a trial altogether because of his health, but ultimately, medical experts ruled that not only was he fit to stand for an indictment, but that he was also healthy enough to start serving his jail term. In December 2011, he was moved from a nursing home to a prison hospital. He died in December 2013, still in the prison hospital.

Boere also stated that at the time, he didn’t think he was doing anything wrong, although his opinion has now changed. According to his judge, though, he was clearly unapologetic.

8Oskar Groening

“The children . . . they’re not the enemy at the moment. The enemy is the blood inside them.”

In early 2005, the “Bookkeeper of Auschwitz,” Oskar Groening, gave an interview to the BBC in which he explained just how it came to be accepted that even the youngest, most innocent of children were included in the Nazi policy of mass extermination. He goes on trial in April 2015, charged with at least 300,000 counts of accessory to murder. Now 93 years old, Groening started working at Auschwitz when he was 21 and was responsible for overseeing the luggage, money, and other possessions taken from those who were shipped to the camp.

Groening’s case is a strange one. After the war, he gave up his military life and went to work at a factory that made glass. He retired, having never spoken of his work at Auschwitz—until he heard the stories about the Holocaust denial movement. It was then that he spoke up as a witness to the atrocities that so many people were suddenly denying ever happened. He spoke freely and openly about the gas chambers, about the selection processes for those condemned to die, and about the crematoria. He saw them all, and unlike so many others that wore the Nazi uniform, he spoke about what they had done.

He also maintains that he had nothing to do with the actual acts of murder that went on at the camp. In 1980, he was brought up on charges for war crimes. Those charges were dropped, but the precedent set by the Demjanjuk verdict means that regardless of what his actual role was, his free admission that he was there and that he was witness to the atrocities means that he can be found guilty.

7Hans Lipschis

Now 95 years old, Hans Lipschis was arrested in 2013 for his connections to Auschwitz. Allegations state that he was a guard at the concentration camp, while Lipschis maintains that he was just a cook. While he has stated that he didn’t know anything about what was going on at the camp, the Simon Wiesenthal Center put him on their list of most wanted Nazi war criminals. The courts decided that there was enough evidence surrounding his four-year stay at Auschwitz to search his home and arrest him.

Lipschis had been living in Germany; after the war he went to Chicago but was forced out of the United States when his Nazi connections came to light. Even though the courts and the government had been aware of his location, it was only after the Demjanjuk verdict that they were able to put together a case strong enough to arrest him. Among that evidence is his SS paperwork, which indicates that he was a part of the SS and that he was stationed at Auschwitz, even though there were rumors circulating that he spent much of the war fighting on the eastern front. The Lithuanian-born Lipschis was also given “ethnic German” status, giving him something of an elevated status among those not born in Germany.

After his arrest, he was confined to a prison hospital. Before going to trial, Lipschis was diagnosed as suffering from the beginning of dementia. Doctors advised that it wasn’t likely he would be able to even follow the trial that he was facing, and he was deemed unfit for trial.

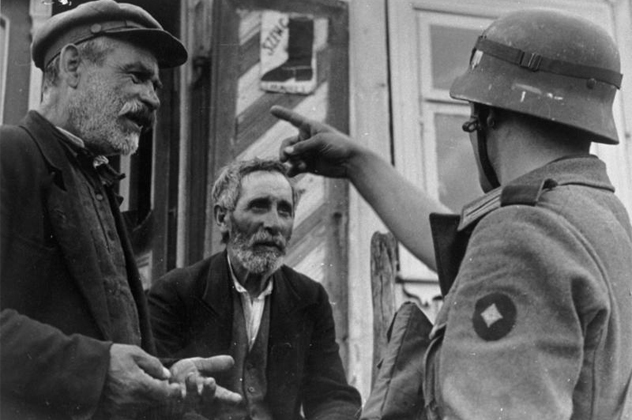

6Vladimir Katriuk

According to a recent academic paper written on the massacre of the Khatyn village, Vladimir Katriuk was an active and willing participant in the atrocities. Khatyn, a village in what is now Belarus, was punished for its stance of German resistance when, in 1943, German troops descended on the village and massacred its inhabitants. The paper names Katriuk in particular, citing his role as machine gunner and testifying that he was the one tasked with shooting anyone who tried to escape the burning barn they had been herded into.

Witness testimonies link Katriuk to this and other atrocities; he, too, is on the official roster of Nazi war criminals that the Simon Wiesenthal Center wants to put on trial. But the Canadian government has seemed ill equipped to deal with him.

Katriuk has been living in rural Quebec for years, supporting himself mainly as a beekeeper. He originally went to Canada under an alias in 1951, and even though the government knew—at least, in 1999—that he had falsified his records on his application for Canadian citizenship, they also found no concrete evidence for why they should revoke that citizenship. When questioned, Katriuk has constantly refused to talk about anything but his bees, not the least bit alarmed about the accusations. His only comments on the accusations? “Let people talk.”

In Katriuk’s case, more evidence has come to light linking him concretely to the village massacre, but the government has been dragging its feet during the investigation of the 92-year-old beekeeper. And that, says Jewish rights groups, is a problem. He’s not the only one that Canada has dropped the ball on, either. In 2009, the Canadian federal court system overruled an attempt to get the citizenship of one-time Nazi guard Wasyl Odynsky revoked. It’s led to accusations from the heads of B’nai Brith, stating that Canada was more likely to let a Nazi war criminal cross their borders than a Jewish refugee.

5Theodor Szehinskyj

Before we lost track of him, Theodor Szehinskyj had been living quite comfortably in an apartment complex in West Chester, Pennsylvania. That was, of course, in spite of a long-ago issued deportation order based on findings that he had been a member of the Waffen-SS Death’s Head Battalion.

In 2000, a motion was lodged against Szehinskyj to revoke his United States citizenship based on the finding of documents that made it quite clear that he wasn’t eligible for asylum under the Displaced Persons Act of 1948. Originally, Szehinskyj had claimed that he had been conscripted into forced labor on an Austrian farm during the war years and was never a member of the Nazi party.

Documents have shown that he left his farm service much earlier than he had claimed, though, and afterward served as an armed guard at Gross-Rosen, Warsaw, and Sachsenhausen. In addition to being a guard, he was responsible for overseeing prisoner transport at the time, too. Those documents made his immigrant visa absolutely invalid; after he had gotten his visa, he had settled near Philadelphia into a job with General Electric. He was naturalized in 1958.

Along with the documents showing that he had been in the Death’s Head Battalion while at the camps, many of the camp survivors testified against him. One of these testimonies was given by Sidney Glucksman. Glucksman, who had been 12 at the time, recounted stories of guards who would put infants and children into bags and then pummel them; other prisoners were then ordered to separate the remains of the bodies from the clothes.

The courts ordered his citizenship revoked and ordered his deportation. But no one wanted him.

With nowhere to deport him to, Szehinskyj stayed in the United States. As of 2013, his address was still the same place in West Chester, Pennsylvania, although his neighbors said they hadn’t seen him in several years. Now over 90 years old, it’s not clear just what happened to him.

4Charles Zentai

Now an elderly man living in Australia, Charles Zentai dodged extradition and accusations based on a technicality. According to a 2012 ruling from the Australian High Court, the accused ex-soldier could not be extradited because, at the time he had allegedly committed his crimes, there was no definition for “war crimes” in the legislature of Hungary.

According to Dr. Efraim Zuroff and the Simon Wiesenthal Center, Zentai was an officer in the Hungarian Army in 1944. Then known as Karoly Zentai, he was tasked with going on regular manhunts through Budapest. Specifically, he was charged with the murder of 18-year-old Peter Balazs. Witnesses identified Zentai, along with fellow soldiers Lajos Nagy and Bela Mader, as the army officers who accosted Balazs for being a Jew and not wearing his yellow star. The teenager was beaten to death, and his body was disposed of in the Danube River.

After the war, their actions caught up with Zentai’s fellow officers. Nagy received a death sentence and Mader received life in prison; Zentai, though, escaped to Australia. In 2005, an international arrest warrant was issued for Zentai; he was arrested, but extradition was put off again and again, with Zentai’s attorney citing poor health. Time and time again, courts ruled that he was eligible for extradition to Hungary, and time and time again, he and his family appealed the decision. By 2010, a federal judge had found that extradition wasn’t an option.

His family has said that while he’ll be more than happy to answer questions, he still maintains that he didn’t kill Balazs and that he wasn’t even in Budapest at the time of the murder.

3Algimantas Dailide

The process to convict ex-Lithuanian Security Police officer Algimantas Dailide began in 2005. Accused of arresting Jews that were attempting to leave Nazi-controlled Vilna and then handing them over to the same Nazi authorities, Dailide was, until 2003, living in the United States with his family. He had become a US citizen in 1955, and until his discovery by the Office of Special Investigations, he was a real estate agent in Florida.

After he left the US, he and his wife settled in a small German town, still on the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s roster of most wanted Nazi war criminals. His name is well documented in the archives of Lithuania, and it’s been confirmed that his insistence that he’s innocent is an absolute lie. During the war, about 94 percent of Lithuanian Jews were killed by the Nazi regime—with help from the Lithuanian Security Police, who were sponsored by the Nazis. The Lithuanian government has made only minor attempts to bring him to court, and one such attempt ended when Dailide simply said that he couldn’t afford to make the trip from Germany. He also made a claim for ill health, citing high blood pressure and chronic back pain. He later begged off by claiming to be the only caregiver for his wife, who was stricken with cancer and Alzheimer’s.

According to the Simon Wiesenthal Center, though, there’s more to the story than that. Lithuania is accused of not wanting to prosecute Nazi collaborators, and when it comes to the possibility of Germany deporting or extraditing Dailide, that’s unlikely—thanks to the European Union’s Nice Treaty, the person needs to be a significant danger to the country before that happens. And given his age and poor health, that’s not a likely ruling.

2Ernst Pistor, Fritz Jauss & Johan Robert Riss

On August 23, 1944, Nazi troops were at the head of one of the worst World War II massacres on Italian soil. Approximately 184 civilians, including 27 children and 63 women, were gunned down after the discovery of resistance fighters in the Padule di Fucecchio. A year later, a British military officer named Sgt. Charles Edmonson returned to take statements from those who survived. The villagers who lived through the massacre told stories about children—including a two-year-old, crying in his mother’s arms—who had been killed by the German soldiers. He kept the statements, and when he passed away in 1985, they found their way to an Italian court.

The documents named Ernst Pistor, Fritz Jauss, Johan Robert Riss, and Gherard Deissman. All were found guilty in absentia and sentenced to life in prison. Deissman died during the trial, and the Italian court has said that they know they’re never going to see the others serve any time in jail. They’re living in Germany, and Italy has no legal standing to force Germany to turn them over. The court also demanded the German government issue a payment to the 32 surviving relations of those killed in the massacre, but Germany declined, citing immunity agreements that had been made with Italy.

Riss lives in a little village south of Munich. He spends his retirement years mostly gardening in a little town where neighbors are skeptical about the charges he’s been convicted of. They’ve known him for decades, and even though he’s out and about on a daily basis, he was given medical leave and excused from the Italian trial. Jauss lives in a nursing home not far away—when the war is mentioned, Riss denies his involvement. Jauss seems a bit baffled that it’s being mentioned at all.

In a rather bitter footnote, the hospital that gave Riss his medical leave from trial was a hospital in Kaufbeuren, which was the home of the Nazi’s T-4 project to get rid of children who didn’t live up to their ideal standards.

1Siert Bruins

Now 92 years old, ex-Waffen-SS Siert Bruins was recently put on trial yet again for his war crimes.

This 2014 trial was for the 1944 murder of a Dutch resistance fighter named Aldert Klaas Dijkema, who was shot in the back after his capture by Bruins’s unit. Although he’s admitted that he was a part of the Waffen and that he was there, he’s said that it was someone else who actually killed Dijkema.

This isn’t the first time he’s been on trial for this murder and others. In 1949, he was given the death penalty for his wartime actions. It was later reduced to life in prison, but he never served any of his sentence. The verdict was handed down in the Netherlands, and Bruins fled to Germany, where he had been given citizenship under Hitler’s policy of naturalizing foreigners who worked with the Nazis. In the 1980s, he was in jail for seven years for another set of murders—a pair of Jewish brothers killed in 1945.

Bruins was ultimately found neither guilty nor innocent. The case against him was dropped because of a lack of witnesses and an inability to prove whether or not he was the one who had actually committed the murder.

The non-verdict was a pretty anti-climactic one, especially considering how long it had taken to catch up with Bruins. Even though Nazi-hunters had found him living under an assumed name in 1978, the killing of a civilian resistance fighter wasn’t even considered a crime until after the precedent set in Hermann Boere’s case. The necessity of changes in the law and precedents—along with the age of the ex-Nazis—makes this all the last chance for justice.