Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

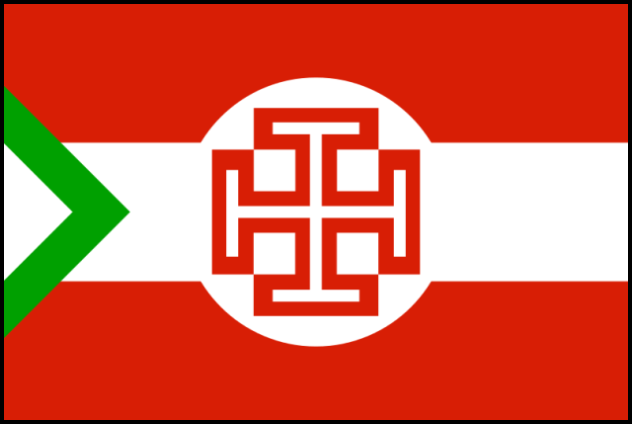

10 Forgotten Fascist Movements Of The 1930s

Nowadays, “fascism” is mostly a misused and little understood word. In particular, it has become a byword for anything in uniform or even remotely right-of-center. But no matter how many times it is howled from megaphones or splashed across banners and signs, fascism is a political ideology that hasn’t had any real power in Europe, its birthplace, since it was summarily defeated during World War II. Sure, neo-fascist political parties still have black-shirted adherents sprinkled throughout major urban centers and on the Internet, but the likelihood of a fascist takeover is slim to nonexistent.

This was not the case in the 1930s. During the decade-long economic depression that affected most of the world, fascism, along with socialism, anarchism, and communism, became popular with two kinds of people—those who saw capitalism and democracy as alien systems forced upon them by the US and Great Britain and those who were disenfranchised with the status quo and sluggish economic recovery. Fascism, no matter what form it took, whether urbane and corporatist or volkisch, combined a hostility to both capitalism and communism with personality cults, grandiose displays of paramilitary (and later military) power and prowess, and a predilection for violence.

While almost all fascist groups were ardent nationalists, fascism as a whole transcended national boundaries. In some places, fascism came to dominate the entire political landscape. Fascism flourished past the 1930s in places like Italy (where Benito Mussolini oversaw the creation of the first true fascist state in history), in Germany (where the model of Italian fascism blended with racialist science, militarism, and populism in order to form an idiosyncratic belief system called national socialism), and in South America (where authoritarian dictatorships became disarmingly common during the Cold War). Elsewhere, fascist movements threatened standing governments and elections but never managed to hold onto power for any real length of time.

10 Francist Movement

Historically speaking, French right-wing groups have always been some of the most active and ideologically driven. Led by intellectuals, former military men, and their own media empires, the French right during the interwar years (1919–39) was particularly powerful and posed a real challenge to French democracy.

On February 6, 1934, the Third Republic was rocked by a violent right-wing demonstration that killed 15 people outside of the Chamber of Deputies in Paris. Spurred on by a financial crisis known as the Stavisky Affair, the riot was widely seen by the French left as an attempted coup d’etat. The major players in the riot were the much older and more cerebral French Action group and the militarist, veteran-heavy Cross of Fire. Alongside these groups was the Francist Movement, an anti-Semitic fascist organization bankrolled by Benito Mussolini, led by a World War I veteran named Marcel Bucard, and defended by a paramilitary organization known as the Blueshirts.

While other right-wing groups in France were somewhat unique in their mannerisms and style of politics, the Francist Movement was a carbon copy of Italian fascism, right down to their use of the Roman salute, the use of the fasces as a symbol of their ideology, and their unequivocal support for Germany, Italy, and a fascist France. By 1936, the Francist Movement and other “anti-parliamentary leagues” were banned by the new left-wing Popular Front government. However, when Nazi Germany invaded France and split it between the German-occupied north and the collaborationist south, followers of the Francist Movement found themselves in power for a short time in Vichy France.

9 Austrofascists

In spite of speaking the same language, Austria and Germany do not share the same culture, so the fact that they took different approaches to far-right ideology shouldn’t be terribly surprising. While Hitler and his followers preached national socialism, Austria subscribed to Austrofascism—a nationalist and authoritarian ideology which was decidedly anti-Nazi. Upholding Austria’s Roman Catholic identity as well as its former position as the center of the multi-national Habsburg Empire, the Austrofascists, who were led by dictator Engelbert Dollfuss’s Fatherland Front, sought to counteract anti-clerical Germany, and any Austrian Nazis who wanted to join Germany, in order to found a single Germanic state in Central Europe.

Although the two groups had been feuding since the 1920s, the Austrian Nazis and the Austrofascists inched closer to internecine warfare after Dollfuss, a diminutive politician and veteran of the Austro-Hungarian army who liked to wear military uniforms decorated with medals and a distinctive Tyrolean feather cap, was named the Chancellor of Austria in 1932. After merging his own Christian Social Party with other right-wing groups in order to found the Fatherland Front, Dollfuss quickly set about establishing a repressive, anti-liberal government.

First he banned the parliament from meeting, then he helped to draft the “First of May Constitution,” which was intended to unite all segments of Austrian society underneath the banner of a single-party state. However, the new constitution sparked a brief civil war between the Austrian right and left (which the right won) and created a burning resentment toward Dollfuss’s government for its decision to ban all opposition parties. In retaliation, over 100 Austrian Nazis disguised themselves as soldiers and police officers and stormed Vienna’s Federal Chancellery in July 1934. During their attempted takeover of the country, the Austrian Nazis shot Dollfuss twice and then refused to let either a doctor or priest see him, thus letting him die a slow, painful death.

8 Rexist Party

Comparable to their like-minded brethren next door in France, the Belgian Rexists were ultraconservative Catholics who envisioned a corporatist state fueled by the dual spirit of nationalism and religious adherence. Unlike most fascist movements at the time, however, the Rexists advocated for the continuation of the Belgian monarchy in the face of widespread liberalism. Led by the charismatic war correspondent Leon Degrelle, the Rexists managed to seat 21 MPs in the face of a resurgent Communist Party during the 1936 election. Then, after entering into a coalition with the VNV (a Flemish nationalist party with fascist overtones) and managing to sway a few voters away from the rival Catholic Party, the Rexists came close to becoming Belgium’s largest and most powerful right-wing party. Until the German occupation of Belgium, this was the closest that the Rexists would get to seizing absolute power.

Although a political movement with many followers, the Rexist Party was in reality a personality cult led by Degrelle. It was Degrelle who decided to push the group more toward Nazi ideology during the late 1930s, even at the cost of the group’s popularity. During the war, Degrelle left the Rexist Party in order to join the Walloon Legion, an all French-speaking Belgian unit in the Waffen-SS. As an officer in the SS, Degrelle fought on the Eastern Front and was awarded numerous decorations for bravery. Degrelle also continued to compose pro-fascist articles for the collaborationist newspaper Le Pays Reel.

After the war, when the Rexist Party was gutted and outlawed like most other far-right parties in Europe. Degrelle fled to Franco’s Spain, where he continued to pen letters and articles defending his actions, the Rexist Party, the Nazis, and the fascist attempt to remake Europe.

7 Russian Fascist Party

Also known as the All-Russian Fascist Party, the RFP was a minor fascist movement led by members of the sizable Russian minority in the Chinese city of Harbin. Using the swastika as their symbol, the RFP made their allegiances well-known throughout the 1930s and 1940s. The Russian Fascist Party wasn’t mere Nazi-worship or a veneration of the Russian Orthodox Church. Instead, the RFP, which was led by Konstantin Rodzaevsky, was composed of many former White Russians (pro-czarist fighters who lost to the Bolsheviks during the bloody Russian Civil War), and it was part of a larger anti-communist network in Russia’s far eastern provinces and in parts of China that contained many Russian expats. In this regard, the RFP was quite similar to the movement led by Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, a White Russian general who established a private empire in Outer Mongolia during the 1920s in order to establish a new Russian monarchy that would recreate the ancient Chinese empires.

Another important element to consider in regards to the RFP was the fact that they were based in the Japanese-controlled puppet state of Manchuko, thus giving them a sort of protected status once Germany and Japan entered into a military alliance. In turn, the RFP assisted the Japanese in various ways, even going so far as to provide intelligence and members for all-Russian units in the Kwantung Army, a provincial branch of the Imperial Japanese Army based in occupied China. As the war began, the RFP was rapidly swallowed up by the Japanese war effort. Then, when the Soviet Army invaded Manchuria, the RFP was crushed, and its leaders were either arrested or killed.

6 Brazilian Integralists

Integralism promotes the idea that a nation is an organic whole, whereby the good of the nation is given priority over everything else. While Integralism was an attempt to unify labor and capital and other elements of the modern state into a corporatist superstructure, it was also a nationalist and ethnocentric cudgel often wielded in order to establish the boundaries between who could and couldn’t be considered a member of an Integralist nation.

In France, Integralism was just one of many reactionary philosophies, while in Brazil, it proved to be one of the most dynamic, if not avant-garde, ideologies of the interwar years. Founded by Hitler look-alike Plinio Salgado, the Brazilian Integralist Action group got its start 10 years before its official formation in 1932. At the 1922 Modern Art Week in Sao Paulo, Salgado and an odd assortment of Futurists, nationalists, and avant-garde artists argued for the creation of a new Brazilian art movement that would embrace both modernism and Brazilian nationalism. This might sound far-fetched, but by 1922, there was already a precedent for modern art helping to create right-wing mass movements. After all, the Italian Futurists helped to give fascism in Italy a visual language of counterrevolution.

Under the slogan of “Union of all races and all peoples,” the Brazilian Integralists, who wore green shirts and adopted the paramilitary poses of the Italian Blackshirts and German Brownshirts, took to the streets of Brazil waving a royal blue flag decorated with the Greek letter sigma. Revolutionary in nature, Salgado’s Integralists espoused anti-Marxist, anti-liberal, and anti-materialist views, some of which were codified in the group’s declaration to engage in a “Revolution of the Self,” the act of subsuming individual wants and desires for the larger social body of the nation. After a tentative peace with Brazil’s President Getulio Vargas, the inevitable crackdown came after a failed 1938 putsch.

5 National Socialist Movement Of Chile

Known as Nacistas, the National Socialist Movement of Chile followed the template created by the German Nazis very closely, including the group’s virulent anti-Semitism. They were led by the triumvirate of General Diaz Valderrama (the founder) and German-Chileans Carlos Keller and Jorge Gonzalez von Marees. The National Socialist Movement of Chile formed its own paramilitary organization, the Tropas Nacistas de Asalto, and began engaging in street fights with rival left-wing parties. The group also argued that Chile was more of a European-style nation and thus superior to its South American neighbors. Declaring themselves as defenders of European values and Christianity, the National Socialist Movement of Chile eventually broke ties with both the Italians and Germans in order to create a more Integralist movement that claimed adherence to democracy.

Throughout the group’s short period of existence (1932–38), Keller provided the Nacistas with an ideological grounding in conservative revolutionary writing. In particular, Keller and others looked to Oswald Spengler, whose favorable opinions of aristocracy and hierarchical societies appealed to Keller’s desire to preserve Chile’s Spanish traditions. But as the National Socialist Movement of Chile began to back away from German Nazism and started forming coalitions with other right-wing groups, some within the party decided to break off and look toward Hitler’s Germany for guidance. The most important of these figures was Miguel Serrano, who combined his unabashed love for Hitler and anti-Semitism with Eastern philosophies and the occult in order establish what he termed “Esoteric Hitlerism.”

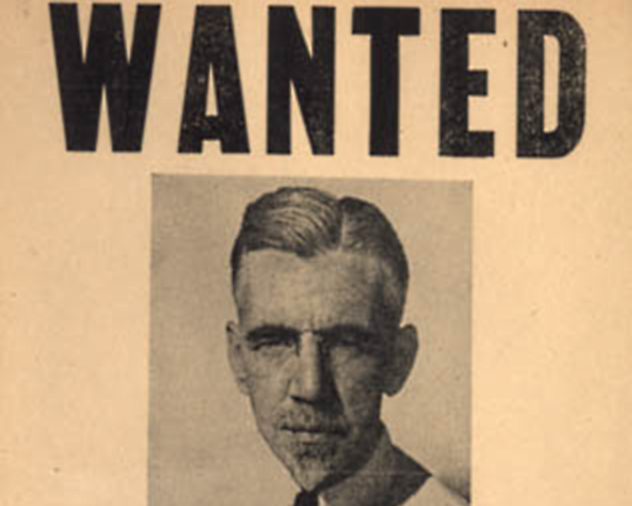

4 Christian Party

Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here satirized the American attitude that fascism was so alien to everyday Americans that it had no chance of ever catching on as a legitimate political movement. In truth, several fascist and neo-fascist movements existed in the US between the World Wars. From the German-backed German American Bund to Father Coughlin’s over one-million-strong National Union for Social Justice, the Great Depression served as an incubator that fostered resentment against the traditional values of American republicanism and democracy. The Christian Party, which was run by the professional agitator William Dudley Pelley, was a much smaller organization, but nonetheless, its Silver Legion came close to forming a European-style paramilitary street gang in the heart of America.

The zenith of the Christian Party came in 1936, when Pelley ran for president as an anti-Roosevelt populist and traditionalist Protestant who swore to rid the American economy of Jewish power and influence. Overall, Pelley garnered a paltry 1,598 votes out of 700,000 in Washington State. Before he could run again in 1940, the FBI raided the Christian Party headquarters in Asheville, North Carolina, and seized assets and equipment under the guise of an embezzlement investigation. Afterward, Pelley and the Silver Legion briefly aligned with the America First Movement, which fought to keep the US out of World War II, but disbanded after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

3 Irish Blueshirts

Though they only existed for two years (1932–34), the Irish Blueshirts were at one point a serious threat to the tenuous democracy of the Republic of Ireland. Originally founded as a collection of former Irish soldiers tasked with protecting the outgoing Cumann na nGaedheal government from the IRA and the supporters of Fianna Fail, who hated the Cumann na nGaedheal leaders for signing the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, the Blueshirts soon began flexing their power as a rabidly nationalist and authoritarian mass movement.

For their part, the Blueshirts believed that they were fighting for Catholic values and the interests of a unified Ireland. In 1933, uniformed supporters of the Blueshirts (who once again took fashion cues from the Italian Blackshirts) took part in the March on Dublin that, like Mussolini’s own March on Rome, was supposed to be a display of size and power. Although the stated aim of the march was to honor war veterans buried at Glasnevin Cemetery, the group’s actions incurred the wrath of President Eamon de Valera, a sworn enemy of the group, who shortly thereafter made the party illegal. Following their disbandment, Blueshirt leader Eoin O’Duffy formed the ill-fated Irish Brigade, which briefly fought on the side of Franco and the Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War.

2 Spanish Falange

The Spanish Falange (meaning “phalanx”) was arguably the most radical right-wing group that fought during Spain’s brutal civil war from 1936–39. Intellectually dissimilar from fellow right-wing groups like the royalist Alfonsists and Carlists and the staunchly Catholic CEDA, the Spanish Falange was founded by the nobleman Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera, who used his skills as an orator to gain big business support for his fledgling group, which was never able to garner many adherents outside of its student base.

What the Falange lacked in manpower they more than made up in zealotry. Like the Italian fascists, the Falange eschewed the traditional tenets of Spanish conservatism (monarchy, church, and family) in favor of aesthetic modernism and a belief in an all-powerful, militaristic state that would expand the size of Spanish imperial possessions. In some ways, the Falange was more akin to its radical leftist opponents during the civil war, who also shared the group’s disdain for clericalism, the Roman Catholic Church, and bourgeoisie morality. Ultimately, this would be the group’s undoing. After first being gutted of their leadership by Spanish Republicans, the group, who committed thousands of men and women to the Nationalist side, were placed into a subordinate position by General Franco after the war.

Franco, who was always more of a traditional conservative, disliked many aspects of the Falangist platform and therefore promoted the Carlists and other groups over the Falange. As a response, many Falangists joined the Blue Division, an all-Spanish volunteer division in Germany’s Waffen-SS. The Blue Division mostly fought on the Eastern Front until 1943, when, under public pressure, Franco ordered all Spanish volunteers to return home. Many Falangists decided to stay in the German Army and signed up for other units, while those Falangists who returned home were suppressed after Falange supporters threw grenades at a Carlist meeting held at the Basilica of Begona in 1942. Demanding retribution, the Carlists and the Spanish Army persuaded Franco to execute Falange leaders before ultimately pressuring El Caudillo into smashing the group altogether.

1 The Iron Guard

The Iron Guard of Romania was more than just one of the most unique fascist organizations in history. Whereas other fascist movements extolled the virtues of nationalism and militaristic discipline above other major concerns, the Iron Guard openly worshiped death. At head of the Iron Guard was Corneliu Codreanu, a handsome mystic and virulent anti-Semite who imbued the Iron Guard with an occult-tinged philosophy that embraced not only anti-liberalism, but also terrorism. Because of this, the Iron Guard, whose motto was “Everything for the Country” became one of the most violent fascist groups of the interwar period.

In 1938, out of fear of the growing power of the Iron Guard and its three death squads, which were tasked with assassinating political opponents and carrying out pogroms against Romania’s Jewish population, King Carol II established a one-party “corporative” with himself as the leader and began outlawing all other political parties. Subsequently, many Iron Guard legionaries were imprisoned or executed. Even Codreanu himself was imprisoned and garrotted to death in November 1938.

Following this purge, the Iron Guard took advantage of World War II and Romania’s troubled neutrality. As Romania began leaning toward the Axis Powers, Guard members allied themselves with General Ion Antonescu, an authoritarian dictator who supported Germany and Italy during their invasion of the Soviet Union with Romanian troops. The alliance between General Antonescu and the Iron Guard was short-lived, however.

For two days in January 1941, the so-called Legionaries’ Rebellion tried to usurp Antonescu’s power. At the same time, the rebellious Iron Guard members carried out a pogrom throughout Romania which killed around 120 Jews and destroyed many homes, businesses, and synagogues. Once the guns stopped, and General Antonescu carried the day, over 200 (some sources say as many as 800) Legionaries were dead and thousands were imprisoned.

Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer based in Boston. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, VICE, Metal Injection, and others. He currently blogs at literarytrebuchet.blogsport.com.