Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

10 Incredible Acts Of Bravery In The Name Of Pacifism

War does incredibly strange things to people. Along with a feeling of nationalism and patriotic pride comes hatred and suspicion, especially against those who refuse to fight. For some, it’s a religious conviction, and for others, it’s simply a belief in nonviolence that makes them a pacifist or a conscientious objector. Even though pacifists have routinely been labeled as cowards, some have made unbelievably brave sacrifices in the name of their beliefs.

10 Arndt Pekurinen

Arndt Pekurinen, from Finland, was 20 years old when he was drafted into military service in 1926. He refused for ethical reasons, and that’s where his problems started. Although he could have chosen to avoid conscription based on religious beliefs, he chose to make his stand on moral grounds. In addition to believing that religious pacifists had every right to have their beliefs honored, he felt that those same rights should be granted to those who were pacifists for other reasons. He refused his conscription on ethical grounds, stating that it was morally wrong for people to be forced to fight and kill.

In 1929, he was arrested and forced into the army, where his policy of nonviolent resistance continued. Eventually, he was handed over to a military hospital and then sentenced to three years in prison. While he was there, the Finnish parliament was bombarded with news stories and public outcry in reaction to his treatment. They eventually rewrote their conscientious objector laws to protect those who protested the war on moral grounds, just the thing that Pekurinen had hoped to raise awareness for.

After his release from prison, he led a generally normal life. He married, had several children, and drove a taxi. When the Winter War began, however, he was drafted again. It was then that he learned that the rewriting of Finland’s conscientious objector laws had come with a strange stipulation: It only applied during peacetime.

Pekurinen was called into duty and once again refused to serve. His execution was ordered without a trial. Two people refused to shoot him. The third one didn’t refuse, and he was shot on November 5, 1941. Pekurinen said, “As people are not eaten, butchering them is of no use.”

9 Franz Jagerstatter

By all accounts, Franz Jagerstatter was something of a loose cannon when he was young. As a village boy, he managed to get a girl pregnant before they were married—something that was frowned upon in 1940s Austria. After eventually marrying another girl, he turned his wild ways around, becoming incredibly devout and dedicated to the Church.

With the shadow of war looming, though, it wasn’t an easy time to be a pacifist. Jagerstatter served in the military briefly through training, but he eventually returned to his farm even more determined not to fight. He was also the lone dissenting vote in his village when it came to Hitler’s annexation of Austria, even though the mayor reported that the vote had come back 100 percent in favor of the Anschluss.

It wasn’t long before he was called into service, and he refused in spite of continued pressure from friends, family, and even his church. He wrote, “I cannot serve both Hitler and Jesus.” When the Nazis moved into town and began offering assistance to farmers, he refused. He also refused to collaborate in any way with a doctrine that he didn’t believe in and stopped going to taverns because of his tendency to get in fights over his outspoken dislike of the Nazis. At the same time, he continued his charity work, although he and his family continued to live in poverty themselves.

First confined to the local prison, he was ultimately transferred to a prison in Berlin. There was no such thing as pacifism or being a conscientious objector in prison. Jagerstatter volunteered to serve in the military as a medical orderly, but his offer was rejected, and he was beheaded in Brandenburg prison on August 9, 1943.

The aftermath of his execution was a strange one. A group of nuns returned his ashes to his home, where they were formally ignored. Only his wife stood by him, and for decades, all public acknowledgment of his actions was forbidden. In a very telling postscript, the judge who sentenced him to death committed suicide not long after his execution.

8 Francis Sheehy-Skeffington

Francis Skeffington was born in 1878 and was not only a pacifist, but an early supporter of women’s rights in Ireland. He was known for resigning his position at University College Dublin over admittance practices that discriminated against women and for taking his wife’s surname when they married. Sheehy-Skeffington was also an active member of the Peace Committee, which was established to try to put an end to Ireland’s fighting, and he was involved in the Irish Citizen Army, which acted as a defensive force.

Sheehy-Skeffington’s involvement in the Easter Rising of 1916 was of a pacifistic nature. He traveled to Dublin in order to help organize civilians who were participating in a defense force with the goal of protecting shopkeepers from looting during the chaos. When he showed sympathy for the Irish rebels deemed as insurgents, he was arrested. Hands tied behind his back, he was escorted into the heart of the uprising by the 3rd Battalion Royal Irish Rifles. Captain J.C. Bowen-Colthurst, in charge of the raiding party, gave his men orders to shoot him first if they were attacked.

Two journalists were arrested in the raid, and the next morning, both journalists and Sheehy-Skeffington were executed. Bowen-Colthurst was ultimately court-martialed after protests by one of his senior officers. Found guilty but insane, he was sentenced to 18 months in an asylum before retiring and moving to Canada—his full pension intact. Sheehy-Skeffington’s wife refused a monetary settlement for her husband’s death, and his execution marked a major swing in popular opinion away from wealthy landowners like Bowen-Colthurst.

7 Jeannette Rankin

Jeanette Rankin, born in 1880, was the first woman elected to US Congress. She ran on a platform that emphasized social issues in 1916—on the cusp of the United States entering World War I. While she was running, she made no secret of her pacifist beliefs in spite of the fact that many of the women she’d previously worked with through the suffragette movement were afraid that her running—and inevitable loss—would set women’s rights back again.

Rankin ended up winning one of Montana’s two seats in spite of statements that look rather strange today. On the prospect of war, she said, “If they are going to have war, they ought to take the old men and leave the younger to propagate the race.”

Sworn in on April 2, 1917, she faced something of a trial by fire. That evening, Congress met with President Wilson to hear his request for a declaration of war. Rankin had run on a platform which made it clear that she was well aware of just how must responsibility was on her shoulders as the first female member of Congress, and she later regretted not participating in the debate. Nevertheless, she held fast to her convictions as one of the 50 members who voted against war. The backlash of hate was immediate, with claims that she wasn’t voting as her state wanted; she was voting as a woman would.

After failing to be reelected to Congress, Rankin took a brief hiatus and filled the time with work in organizations like the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. When World War II was clearly looming on the horizon, she returned to Montana with her sights set on replacing the anti-Semitic Jacob Thorkelson, and she did. By the time she was elected, the country was indirectly involved in the war, and she even went as far as introducing resolutions that would prevent the military from sending troops outside the Western Hemisphere. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, she voted “no” again—the lone vote in opposition to the war.

Rankin felt the immediate backlash, from being cornered in a phone booth until a police escort could rescue her to a telegram from her brother informing her that her state was 100 percent against her. She didn’t run again, stating that, “I have nothing left but my integrity.” She also stated that because she was a woman, she was unable to go and fight and couldn’t bring herself to cast a vote that would send others.

6 Archibald Baxter

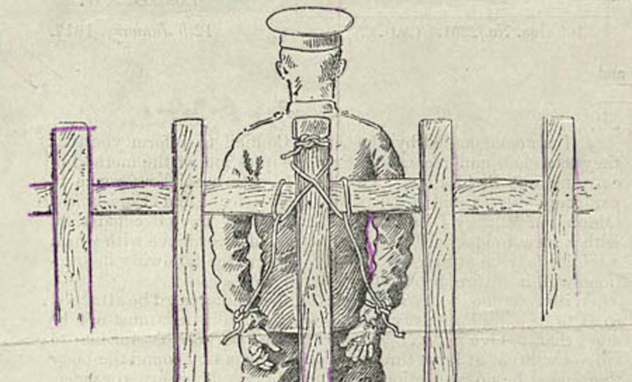

In 1917, New Zealand was having none of this conscientious-objector malarkey and dealt with their protesters by sending them to the front lines. Among the 14 conscientious objectors sent to the front lines in France was a farm laborer and devout Christian named Archibald Baxter. Baxter and six of his brothers had already served jail time for their refusal to enter military service. When the minister of defense declared that the overcrowding in prisons due to the domestic collection of pacifists should be alleviated by sending the men to the front lines, Baxter and two of his brothers were among those chosen to go.

Once there, the chosen method of convincing the men to fight and take up arms was torture. Baxter, who particularly gained the ire of his commanders, and the others were subjected to “crucifixion,” which meant being tied to a post, outside, in any weather, for hours at a time. When crucifixion, beatings, and the threat of execution were unsuccessful, Baxter was sent to the trenches in a heavy fire zone. There, he was starved in the hopes of breaking him. On April 1, 1918, almost a year since he and his brothers had been forced to leave New Zealand, Baxter was removed to a Bologne hospital, where he was declared insane. With a concurrent diagnosis from the British (likely exaggerating his condition out of sympathy), he was sent home in August.

Baxter married three years later to a girl named Millicent Brown, who found him after reading of his ordeal. His oldest son would be imprisoned after taking a similar stand during World War II, and the book that Baxter ultimately wrote became one of the country’s leading works on pacifism.

5 Ben Salmon

Ben Salmon registered with his local draft board in June 1917, but he wasn’t happy about it. He felt so strongly about his pacifist beliefs that he wrote a letter to the president damning the decision to go to war. The letter read, in part, “I refuse to submit to conscription. Regardless of nationality, all men are my brothers. God is ‘our Father who art in heaven.’”

Salmon also refused to accept conscription in a nonviolent, noncombatant form, based not on the Quaker or Mennonite faith that many pacifists cited, but because he was a Roman Catholic. The working-class railroad union organizer was once a supporter of Woodrow Wilson, largely because of his anti-war stance. When Wilson declared war a necessity, Salmon was faced with a dilemma—support his country or stay true to his beliefs, his religion, and the teachings of his parents. The newly married 28-year-old chose his faith, but his status as a conscientious objector was refused because, according to US law, the Roman Catholic Church allowed for its members to go to war when the cause was just. Clearly, this was a just cause.

Salmon was quickly arrested but continued to speak out against the war. His views were so unpopular that he was even kicked out of the Knights of Columbus, and when laws were changed to make conscientious objectors subject to military law, he was court-martialed and sentenced to death, a sentence which was eventually reduced to 25 years in prison.

That prison was Leavenworth, where he held onto his pacifist beliefs even in the face of family tragedy. In 1918, his brother visited him for Christmas, and after harassment from the guards and a streetcar strike, Joe Salmon was turned away from the prison for a second visit and cast out into the Denver winter. He caught pneumonia and died only a few days later. Ben was not allowed to attend the funeral.

After two years, Salmon committed to a hunger strike. Two weeks in, guards began to force-feed him, but he was eventually transferred to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for the Insane. Released from his prison sentence, he was allowed to go free. He died at 43 years old having never truly recovered his health.

4 Dr. Max Josef Metzger

Max Metzger was at the head of several “secular” institutions in Austria throughout the 1920s, including the Mission Society of the White Cross and the Peace League of German Catholics, which worked to bring an end to war and conflict. His focus was not only on promoting peace, but also abstinence and fighting the effects of alcohol abuse. Throughout the decade, he traveled Europe, speaking to those who would be conscientious objectors and commending them for following the teachings of the Church. He condemned religious hatred and anti-Semitism, writing of Hitler, “I would have no qualms about shooting him if I could thereby save the lives of thousands of people who will have to die because of him. Even if I were torn apart in the process.”

He published his thoughts on Hitler and the Third Reich openly and ultimately drew the attention of the Gestapo. He was arrested in 1934. Although he was released quickly and made it a point to turn his work to a more religious nature, he was arrested again in 1943, again by the Gestapo, and was charged with being a freedom fighter.

The man who had received support from the Pope on his views about democracy and respecting people of all races, ethnicities, and nationalities was beheaded on April 17, 1944, the 30th prisoner to go to the chopping block at Brandenburg-Gorden Prison that day. His executioner would later note that he had been at peace as he walked to his death.

3 Dietrich Bonhoeffer

In hindsight, it might seem pretty clear that Hitler’s policies were in direct opposition to pretty much all of the teachings of the Catholic Church. At the time, though, pastors like Hermann Gruner took a different viewpoint, claiming that Hitler’s rise to power was nothing less than the opening of the door to Christ and Heaven. While a lot of this was undoubtedly said out of fear, German-born theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer was having none of it.

Living first in Spain and then at a US seminary before returning to Germany, Bonhoeffer was fresh out of school when Hitler came to power. As Hitler was rising, Bonhoeffer was speaking out against what he called “cheap grace,” which was his term for going through the motions of Christianity and then not backing those beliefs up with action. Already banned from teaching, Bonhoeffer taught pacifist ideas and religious action in an underground church. When even that church was no longer willing to speak out against the growing Nazi party, he was forced to rethink his tactics.

Bonhoeffer originally signed up with the German secret service, becoming a double agent and using his position within his church to set up safe routes for Jews escaping the Nazi regime. Eventually, he was recruited into a plot to assassinate Hitler along with his brother-in-law, Hans von Dohnanyi. Bonhoeffer was recruited by General Hans Oster to act as a messenger between the German conspirators and the British government. All the while, he was writing on the moral dilemma that he was facing, asking himself what made a choice right or moral and whether or not it was even possible to know the difference.

Bonhoeffer was captured in April 1943. He was sent first to Tegel, then to Buchenwald, and finally to Flossenburg, where he was hanged only a month before the German surrender. Those who witnessed his execution described him as a composed and devout man, relying on his faith in God and his belief that only God could determine what actions were right or wrong.

2 Wilhelm And Wolfgang Kusserow

Born into a family of Lutherans who later became Jehovah’s Witnesses, Wilhelm (born in 1914 and named after Germany’s emperor Wilhelm II) and Wolfgang (born in 1922) lived with their parents in Bad Lippspringe, which was known for its strong ties to the Jehovah’s Witnesses. When the Nazis rose to power, the devotion of the Jehovah’s Witnesses to God instead of the fuhrer became a problem, and the family was consistently harassed by the German police.

Even after seeing their father arrested twice, the family continued to host Bible readings and study. In 1939, Wilhelm was also arrested for refusing the call to join the German army. Put on trial for his refusal, he was given a choice: Deny his faith and serve Hitler or die. Wilhelm refused and received the death sentence. It was carried out in Muenster Prison, where he was taken before a firing squad on April 27, 1940.

Wolfgang was arrested in December 1941 for also resisting his induction into the German army. Like his brother, he cited his religious beliefs and his faith in God above Hitler for his decision to decline to fight for the Nazis. His devotion to the commandment, “Thou shalt not kill,” echoed that of his brother’s, and he, too, was given the death sentence. On March 28, 1942, he was sent to the Brandenburg Prison guillotine and was beheaded.

1 Carl Von Ossietzky

Born in a small village on the border between Germany and Poland in 1889, von Ossietzy spent two years working as a journalist before being called to military service during World War I. By the time he left the war, he had taken a staunch pacifist stance. He was active in the German Peace Society and traveled through the country giving speeches. He wrote for a number of anti-war publications, including Die Weltbuhne (“The World Stage”), which published articles on Germany’s rearmament actions. He received a brief prison sentence for his writings. Not long after his release, he ran an article on Germany’s violations of the Treaty of Versailles and received another jail sentence, convicted of treason against his country. Released in 1932, he was rearrested again in 1933. This time, he was sent first to a prison in Berlin and then to Sonnenburg’s concentration camp.

Though von Ossietzky had chronic ill health, he was sentenced to hard labor in spite of previous heart attacks and a diagnosis of tuberculosis. In 1934, he was suggested for a Nobel Peace Prize by his German colleagues from Die Weltbuhne, who kept writing from Paris. The nomination came too late that year, but he was awarded the prize in 1936 as he languished in a concentration camp, his remaining days being slowly drained away by his tuberculosis. Germany refused him the passport that would have been necessary for him to go to Norway to collect his prize, and he ultimately died under guard in a civilian hospital in May 1938.

One of his last interviews was given in 1937, when he had nothing but good things to say about the Nazi party to Time magazine, which noted just how exhausted by life he was. His last public appearance was incredibly bitter. He had hired a lawyer to go to Norway and collect the prize money for him, but the lawyer was a fraud and kept the money for himself. The money was recovered in court, but those court appearances would be the last appearances of an exhausted, beaten man.