History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Notable Struggles Of The Russian Civil War

The popular view of the Russian Civil War that followed the Russian Revolutions of 1917 is a two-party conflict between the Bolsheviks with their Red Army and the anticommunist White Movement with their White Army. But it was actually far more complicated and messy.

Among the many factions were various types of socialists, anarchists, monarchists, nationalists, capitalists, and peasants defending their homes. International powers also intervened. From 1917 to 1922, Russia was a hellscape of competing interests, resulting in many strange struggles for power.

10 Operation Faustschlag

When the Soviets seized power in 1917, Vladimir Lenin immediately announced that Russia was withdrawing from World War I and entered into talks with Germany in the Polish town of Brest Litovsk, quickly arranging an armistice for the eastern front. Heading the Russian delegation, Leon Trotsky tried to play for time, believing that a revolution in Germany was imminent. Instead, the Soviets were shocked by the German demands for indemnities and land concessions.

Trotsky pursued a policy of “no war, no peace.” Two days before the armistice expired, he told the stunned German negotiators that Russia considered the war over. This wasn’t good enough for the Germans, who wanted something on paper so they could move troops to the west. They responded by making a separate peace with Ukraine and telling the Russians that Germany would resume offensive military operations in Russia.

Operation Faustschlag (meaning “fist punch“) began on February 18, 1918. The Germans encountered little to no Russian resistance, advancing 240 kilometers (150 mi) in one week, with the only major impediments being bad weather and substandard communications. After seizing the cities of Pskov and Narva, they moved toward Smolensk. At the same time, Turkish forces in the Caucasus reached Baku. With the Germans within 160 kilometers (100 mi) of Petrograd, the Soviets were forced to move their capital to Moscow.

Although most of the Soviet leadership wanted to continue fighting, most of the army had been destroyed or disbanded by the Bolsheviks. So the Russians were forced to make peace. Lenin assured the leadership that it was only a temporary measure to preserve Bolshevik control of Russia. The Treaty of Brest Litovsk was signed, ending Operation Faustschlag. But German operations continued for a time in the Caucasus and Crimea. The Germans later captured Helsinki and occupied Finland.

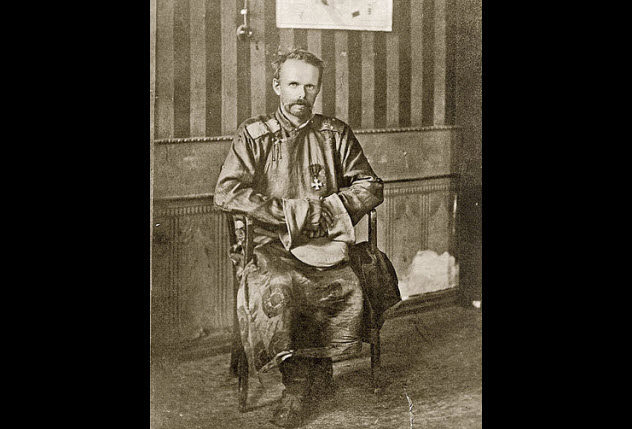

9 Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg

Born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire but raised in Estonia, Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg served in the Russian navy as a cadet and then volunteered to fight in the Russo-Japanese war. He was demoted for violent behavior but permitted to stay due to his aristocratic connections.

Convinced that Russia and Japan would come to blows again, von Ungern-Sternberg sought to position himself in the Far East to participate. After a quick expulsion for drunkenness from the Argun Division of the Trans-Baikal Cossack force, he joined the Amur Division, becoming enamored of the cultures of Dauria and Xinjiang as well as Mongolian and Tibetan Buddhism.

When World War I erupted, von Ungern-Sternberg rode 1,600 kilometers (1,000 mi) from Dauria to Blagoveshchensk to fight in Prussia, later joining the Whites after the revolution. Defeated by the Reds, he fled east, becoming governor of the Dauria region under the command of Japanese-supported Cossack Ataman Semenov.

Von Ungern-Sternberg ruled with terror, slaughtering Jews and Bolsheviks in a period known as the “Atamanschina” (the “time of the Atamans”). He eventually turned on Semenov and raised a private army of Russians, Mongols, and Buryats to conquer Mongolia. There, he expelled the Chinese, captured the capital, Urga (which is now Ulaanbaatar), restored Bogd Khan to the throne, and made himself the dictator.

Von Ungern-Sternberg dreamed of restoring the Russian monarchy and building a Eurasian empire under his own command that stretched as far south as India. He was known for the bloody executions of Jews, communists, and others, including beheadings, immolation, dismemberment, disembowelment, naked exposure on ice, wild animal attacks, dragging people with a noose behind a car, forcing victims to climb a tree until the person fell out and was shot, and tying people to tree branches which were bent back by his men so the victim would be ripped apart when released. He became known as the “Bloody White Baron.”

His bizarre regime forced the Soviets to send troops to help the Mongolians defeat him. The Soviets had previously ignored Mongolia to concentrate on securing their holdings in Siberia and the Far East but were forced to deal with this highly destabilizing influence on their flank. Von Ungern-Sternberg was captured and executed by the Soviets in 1921.

This intervention may have helped the rise of the Soviet-supported Mongolian People’s Republic, which retained independence despite a 1924 Sino-Soviet treaty which recognized Chinese sovereignty over Mongolia.

8 Czechoslovak Legion

The 60,000 men of the Czechoslovak Legion fought for Russia in World War I in the hope of freeing their homelands from Austro-Hungarian rule. They had begun as four foreign volunteer rifle regiments of Czechs and Slovaks who either lived in the Ukraine or had defected from the Central Powers and were now fighting for Imperial Russia. Thomas Masaryk asked to assemble a full Czechoslovak army, a request which was granted by the provisional government when Tsar Nicholas II abdicated in 1917.

But the Bolsheviks soon seized power and made peace with the Central Powers, who viewed the Czechoslovak Legion as traitors to be executed. Hoping to join Allied Forces in the west and with German forces closing in on their bases in the Ukraine, the legion decided that the safest way to reach Flanders was through the Pacific. Within a few days, they commandeered trains to take the legion east.

After resisting a Soviet attempt to disarm them at Chelyabinsk, the legion converted railcars into barracks, bakeries, workshops, and hospitals, moving slowly along the Trans-Siberian Railway, capturing cities and telegraph stations along the way.

They allied with the White Russian forces and soon controlled an area stretching from the Volga to the Pacific. In June 1918, the legion captured the port of Vladivostok, declaring it an Allied protectorate. Lauded by President Woodrow Wilson, the legion was soon supported by American, Canadian, British, French, Italian, and Japanese troops.

However, as the White Russian forces collapsed, the Czechoslovak Legion was trapped by encroaching Bolshevik troops. A deal was struck: In exchange for tsarist gold captured by the legion at Kazan, the Bolsheviks would give the legion time to be evacuated by the Allies.

The legion was transported to Europe via the Indian Ocean, the US, and the Panama Canal. Their contribution in the fight against the Bolsheviks likely influenced the decision of the US government to recognize Czechoslovakia as an independent country.

7 Yudenich’s March On Petrograd

In 1919, the Whites captured a number of cities in the Baltic region. The Imperial General Nikolai Yudenich wished to press on to capture the capital of Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) from the Soviets. He enjoyed the advantage of six tanks manned by British crews as well as the support of the British navy in the Gulf of Finland. Moving quickly, he seized Pskov, Jamburg, Krasnoe Selo, and Gatchina and was seemingly poised to capture Petrograd.

The leaders in Petrograd warned Lenin that Yudenich had an advantage in automatic rifles, planes, tanks, and British naval support. They urged the abandonment of the city. Lenin thought the White moves in the north were a distraction from the more serious conflict in the south. But Trotsky argued that the city could be held, so he was put in charge of its defense.

Ultimately, Trotsky was proven right. Yudenich depended too much on his British tanks and naval support. His army numbered only 25,000 men. The Soviets were able to field a much larger army, which attacked Yudenich’s forces as they neared the city. The White Army was routed when Trotsky launched a counterattack.

The survivors fled to Estonia, where they were disarmed by the Estonian government, which hoped to secure peace with the Soviet government. The city of Petrograd was awarded the Order of the Red Banner and a Revolutionary Red Banner of Honor.

6 Makhno’s Black Army

During the Russian Civil War, Ukraine had many competing factions: Bolsheviks, Whites, Nationalists, Cossacks, Polish invaders, peasant insurgents, deserters, bandits, and warlords. But perhaps the most notorious force was Nestor Makhno’s anarchist Black Army.

Born in 1889 in the Ukrainian city of Guliai Pole, Makhno became involved in the failed 1905 revolution that rocked Russia after its defeat by Japan. Arrested in 1908 for being a member of a revolutionary cell, he spent eight years in a Moscow prison before his release under a political prisoner pardon by the provisional government. He returned to Guliai Pole to organize peasant unions to oppose the landowning kulak class, which consisted mostly of German Mennonites resented by the Ukrainians.

After the Treaty of Brest Litovsk was signed, former cavalry officer Pavlo Skoropadsky became hetman of a new Ukrainian-German vassal state, which lost most of its control after the collapse of the Central Powers in 1918. Makhno raised the black flags of his Revolutionary Insurrectionist Army, defeating a much larger army of kulak militiamen at Dibrivki Forest.

With a Ukrainian Socialist Republic declared, the Bolsheviks preparing to invade, the White Army under Anton Denikin occupying the country, and Polish forces under nationalist Jozef Pilsuduski invading the western regions, Ukraine was in chaos. Makhno used the madness to turn his Black Army against the kulaks, burning and looting estates, farms, and country houses. Makhno had no reservations about committing atrocities against the German Mennonites and tsarists, leading the usually pacifist Mennonites to form an armed force called the “Selbstschutz” in self-defense.

The anarchists showed surprising military discipline and developed an astounding proficiency for modern horseback warfare. They developed a horse-drawn mobile weapons platform called the tachanka, which was later copied by the Soviets. The Black Army was instrumental in defeating the Whites in the Ukraine, occasionally becoming allies with the Reds to accomplish this goal.

But the Bolsheviks had little gratitude. As the Red Army pushed south, they turned towns held by the Makhnovists into soviets and hanged the anarchist partisans. Disease and constant Bolshevik attack decimated the anarchist forces. The Soviets laid the blame for many of the atrocities in the Ukraine squarely at the feet of the Black Army, although they had been committed by all sides. Forced to flee the country, Makhno died in Paris in 1934.

5 Kokand Autonomy

After the Soviets had invaded Central Asia and toppled a provisional government in Tashkent, a group of Muslim clerics called the “Ulema Jamiati” met to discuss their response to the new government. They proposed setting up a coalition government with the Soviets, but their proposal was rejected by the newly formed Sovnarkom (aka the “Council of People’s Commissars”) on the basis that the Muslims were untrustworthy and had no proletarian organizations to participate in the government.

The Ulema Jamiati were miffed and reached out to their old Central Asian political rivals, the Milli Markaz (aka the “National Center”), meeting with them in the city of Kokand for the Fourth Congress of Central Asian Muslims. There, they announced a new government for Turkistan with a 54-member regional council.

They turned against the Soviets when the Reds opened fire on civilians in Tashkent who were celebrating the announcement of the Kokand Autonomy on the Prophet’s birthday. The Soviets claimed that the civilians were demonstrators who had freed prisoners. The Kokand Autonomy sought foreign alliances but failed to secure support. They were also stymied in their efforts to raise money to purchase arms.

Then the Soviets broke through a blockade of the region by Cossack leader Ataman Dutov. Along with troops raised from Austro-German prisoners of war and Armenian dashnak fighters, the Soviet forces attacked the Kokand Autonomy. In a week, the city was largely destroyed. Over 14,000 people were killed, putting an end to the dream of autonomy.

4 Polar Bear Expedition

Few know about the disastrous deployment of American troops to northern Russia following the end of World War I. Large stockpiles of military equipment and supplies had been sent by the Western Allies to aid the tsar. Stored in warehouses at the northern Russian ports of Murmansk and Archangel, these stockpiles needed to be secured to keep them out of Bolshevik hands and allow them to be redistributed to the White forces, which were supported by the Allies.

The cities were also strategically important entrances to Russia that were still held by White forces. Some politicians believed that Allied support was needed to help the Whites rally to defeat Bolshevism.

In 1918, 5,500 soldiers of the 339th Infantry and support units, primarily composed of troops from Michigan and Wisconsin, were sent to Archangel in the “Northern Russian Expedition” (or more popularly, the “Polar Bear Expedition“). With the tacit goal of fighting the Bolsheviks, they joined an international force commanded by the British. They were to advance south and east to link up with scattered anti-Bolshevik Russian forces and fight the Reds, but most of the battles were inconclusive or inconsequential. Morale suffered after Armistice Day was announced in Europe.

In 1919, two companies of the US Army Transportation Corps accompanied the soldiers to maintain a railroad. The expedition was stymied by the horrible conditions of a Russian Arctic winter and unclear reasons as to why the Americans were even fighting there. The local population also resented the Allied presence and had little enthusiasm for fighting the Reds.

Today, the expedition is seen as a cautionary tale of mission creep, which ended in fiasco. French, White Russian, British, and American troops revolted against the ambiguous campaign. The Allied forces withdrew in humiliation, leaving the White Russians to the tender mercies of the vengeful Bolshevik forces. The expedition failed because it lacked knowledge of local conditions, a clear objective, and a plan of engagement.

There was also confusion among the different agencies and nations involved in the fighting. Some say the intervention only served to make things worse. Russian professor Vladislav Goldin explained, “From our point of view, without the Allied intervention, the anti-Bolshevik struggle in the north could hardly have taken the form of civil war.”

3 Nikolayevsk Incident

In 1919, White General Alexander Kolchak ruled a fiefdom from Omsk, supported by the Japanese who were bitterly resented by Russian partisans for their repressive policies. After a Japanese unit was almost wiped out by partisans, the Japanese retaliated by killing the 232 inhabitants of the village Ivanovka. Such massacres were perpetrated by both sides, but the most notorious became known as the “Nikolayevsk incident.”

With a population of 450 Japanese fishermen, traders, and their respective families, Nikolayevsk was occupied by infantry troops of the Imperial Japanese Army in 1918. In January 1920, the town was surrounded by Bolshevik troops under the command of Yakov Triapitsyn. A truce was arranged that allowed the Reds into the city, but they were attacked by the Japanese when the Japanese discovered that the Bolsheviks were executing anyone they believed to be supporting the Whites.

The Japanese were defeated, with Triapitsyn ordering the execution of the remaining 300 prisoners in revenge. Then the Bolshevik troops turned on the civilians, wiping out most of the population (including all the Japanese) and leaving the town in ruins before a Japanese relief force succeeded in retaking it.

A non-Bolshevik commission from Vladivostok surveyed the aftermath: “Everywhere, as far as the eye could reach, there were only ruins of houses—here and there lonely house chimneys, the tall chimney of the blown-up electric plant, half-sunken vessels. [ . . . ] Almost no inhabitants were seen. Only when the steamer drew nearer, did lonely figures appear, all in black, all humped and bent.”

Survivors reported that the Reds had burned down wooden houses with kerosene and executed women and children. Then they threw the bodies in the river and murdered people with rifle butts, sabers, and bayonets.

The Japanese were furious at the massacre, condemning the barbarity of the Red troops. Though Triapitsyn was later executed by the Soviets, the Japanese used the incident as a pretext for occupying northern Sakhalin Island and for prolonging the Japanese occupation of Siberia for another two years.

2 Decossackization

In 1919, the Bolshevik government instituted a policy of “decossackization,” which was designed to eliminate the Cossacks as a social class and semi-independent political force, especially the Don and Kuban Cossacks. This was the first time that the Bolsheviks had enacted a policy to eliminate an entire social class as collective punishment for real and imagined crimes against the Bolsheviks.

On January 24, a secret resolution of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party called for “mass terror against rich Cossacks, who should be exterminated and physically eliminated to the last.” In February and March, the Red Army advanced into the Don region, massacring any Cossacks who fell into their grasp.

Within a few weeks, between 8,000 and 12,000 Cossacks were killed. Two months later, the secret resolution was withdrawn due to the rising Cossack insurgency and opposition by some party members. But persecution of the Cossacks continued in other ways.

In 1920, separate Cossack soviets were abolished, and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic took over government administration of the Cossack regions. In June, Cheka leader Karl Lander was made plenipotentiary of the Kuban and the Don. He established tribunals that sentenced thousands of Cossacks to death and sent members of Cossack families to concentration camps.

Toward the end of the year, five Cossack boroughs—Kalinovskaya, Ermolovskaya, Romanovskaya, Samachinskaya, and Mikhailovskaya—had their entire populations exiled to the Donets Basin to serve in the mines as forced labor.

Many Cossacks fled the country, settling in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia and later joining the German army en masse during World War II. In 1945, the British handed over 35,000 Cossack prisoners of war to the Soviet Union for summary execution.

While Soviet attitudes toward the Cossacks later softened, the experience of decossackization was long remembered. The Cossack movement used it as evidence that they deserved recognition as a persecuted class during the glasnost period of the 1980s.

1 Kronstadt Rebellion

Built by Peter the Great in the 18th century, Kronstadt was a fortified Russian city and naval base on Kotlin Island in the Gulf of Finland. In 1921, Kronstadt was also the home base of the Soviet Baltic fleet. Its sailors had long harbored revolutionary sympathies, having commandeered a cruiser in 1917 to sail up the Neva River and open fire on the Winter Palace.

During the revolution, they also turned against their officers—jailing, lynching, or drowning them. According to Trotsky: “The most hateful of the officers were shoved under the ice, of course while still alive. [ . . . ] Bloody acts of retribution were as inevitable as the recoil of a gun.”

By 1921, the sailors at Kronstadt were angry at the Bolshevik government. On the practical side, they were forced to endure low wages, food and fuel shortages in the winter, and the unequal distribution of food that favored those in power.

In a political sense, they were furious at the Soviet suppression of political dissent, the lack of democracy, and the rigors and abuses of so-called “War Communism.” On February 28, they issued the Petropavlovsk Resolution, which included demands for national elections by secret ballot, the freedom of speech and assembly, the release of political prisoners, the cessation of forced labor, free markets for the peasantry, the freedom to form trade unions and peasant assemblies, an end to grain seizures, the removal of communist political agencies from the military, and freedom of the press for all socialist parties.

In a letter, Trotsky characterized the mutiny as an uprising by a “grey mass with great pretensions, but without political education and without a readiness to make revolutionary sacrifices.” With 20,000 Red Army soldiers sent to defeat the 15,000 rebels, artillery duels decimated both sides as the Red Army advanced across the frozen Gulf of Finland. Aerial bombardment also weakened the rebel defenders. The Red Army defeated the sailors, killing 500 and wounding over 4,000. More rebels were either executed in the aftermath or absconded to Finland.

Trotsky blamed the revolt on the influence of Makhno and the incompetence of Cheka secret police leader Felix Dzerzhinsky. Some believe that the suppression of this revolt was the turning point where the Soviets lost sight of their original revolutionary goals and embarked on the path of totalitarian terror. In the aftermath, the New Economic Policy was enacted to ease the suffering while the Bolsheviks clamped down even more on political dissent.

David Tormsen is always interested in conflicts where there are no clear good guys, especially when there are as many sides as this. Email him at [email protected].