Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 German World War I Aces As Feared As The Red Baron

Manfred von Richthofen, the infamous Red Baron, was the most successful German fighter pilot of World War I. However, there were other German aces who were arguably better and more skilled than he was.

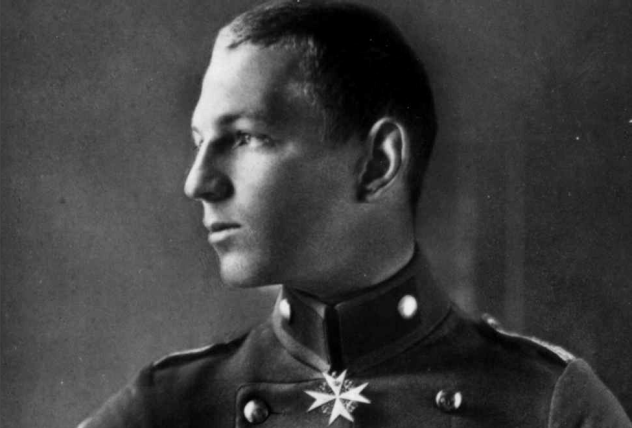

10 Max Immelmann

The legendary Max Immelmann was Germany’s first ever ace. He was also the first aviator to be decorated with the country’s highest military medal, the Pour le Merite, which became known as “The Blue Max” in his honor. Born in September 1890, Immelmann rejoined the German military as a pilot when the war began. He had previously enlisted as a 14-year-old cadet before leaving in 1912 to study.

During his first assignment (to deliver supplies and mail between aerodromes), Immelmann was honored with the Iron Cross, Second Class, for landing his badly damaged aircraft within German lines. His first victory came on August 1, 1915, when he downed one of 10 British aircraft that attacked Germany’s Douai aerodrome, earning him the Iron Cross, First Class.

In October 1915, Immelmann single-handedly protected the French city of Lille from being captured by Allied pilots. This earned him the nickname “Adler von Lille” (“The Eagle of Lille“) from the German public. In one of his exploits over the skies of Lille, he came across the duo of Captain O’Hara Wood and Ira Jones in a BE-2c. Although they had lost their gun early into the battle, they were lucky to escape unhurt, as Immelmann ran out of ammunition. By January 1916, he’d become Germany’s first ace after his eighth dogfight victory and was awarded the Pour le Merite.

On June 18, 1916, The Eagle of Lille met his end. Like many aces, the cause of Immelmann’s death is disputed. While the Allies claimed he was shot down by Lieutenant G.R. McCubbin and his gunner, Corporal J.H., in an FE-2, German authorities stated that he was the victim of friendly anti-aircraft fire. The final tally of Immelmann’s dogfight victories is put at 15, although some sources believe it stood at 17.

9 Oswald Boelcke

During wars, very few people are revered by both sides. Oswald Boelcke was one such person during World War I. He entered the army at the advent of the war in 1914 as an observer with his brother, Wilhelm. He soon transferred to a fighter squadron, Section 62, where he scored his first kill in August 1915. He became friends with Max Immelmann, and they formed a fruitful rivalry.

In January 1916, Boelcke scored his eighth victory on the same day as Immelmann, becoming Germany’s second ace. They were the first pilots to be awarded the Pour le Merite. After Immelmann’s death in June, Boelcke was ordered by the kaiser not to fly for one month to prevent losing him. While on the ground, he pushed for reforms that led to the reorganization of the Imperial Army Air Service. Preaching the use of formation fighting instead of individual efforts, Boelcke inspired the establishment of the Jasta squadrons. As the leader of the newly established Jasta 2, he picked the trio of Manfred von Richthofen, Hans Reimann, and Erwin Boehme as his underlings.

Although Boelcke had the blood of many Allied pilots on his hands, he also garnered fame as one of the few gentlemen pilots to grace the skies. Days after his first victory, he saved a French boy from drowning in a canal near a German aerodrome. He was honored with the Prussian Lifesaving Medal after every effort by the boy’s parents to have him awarded with the French Legion d’Honneur was rebuffed. Another memorable exploit of his took place in January 1916, when he brought down two British flyers. While visiting one of the pilots in the hospital, he was handed a letter to deliver, which he did by dropping it behind enemy lines despite heavy fire.

Boelcke lost his life on October 28, 1916, when his plane collided with Boehme’s. At the time of his death, the 25-year-old was the leading ace with 40 dogfight victories. Boelcke’s legacy, aside from being the father of the German air force, included writing Dicta Boelcke, the first book to contain the basic rules of air combat. Even long after his death, his proteges, especially the Red Baron, held him in high regard.

8 Lothar Von Richthofen

Mostly remembered today as only the younger brother of the Red Baron, Lothar von Richthofen was still a prolific ace during World War I, thought by some to be even deadlier than his famous brother. Born two years after Manfred, Lothar was a cavalry officer before the war broke out. He switched to the Imperial Air Service after getting his wings in 1915. He flew as an observer with Jasta 23 until 1917, when he was transferred to Jasta 11, the squadron that his brother was part of at that time.

After his first victory on March 28, the younger Baron quickly stepped out of the shadows of his prolific brother, gaining 24 victories in a month and a half. Among the casualties of his early surge was his disputed victory over famous ace Albert Ball. He was awarded the Pour le Merite on May 14. Recognized by his peers for his aggressive style of combat, Lothar spent as much time in a hospital bed as he did in battle. After another spell in the hospital, Lothar was back to the war front for a few months before he was again shot down on August 12, 1918, thus ending his war.

After the war, Lothar worked briefly at a farm before becoming a commercial pilot. He lost his life in a flying accident in July 1922. Credited with 40 victories, the young Richthofen could have been as legendary as his brother if he had adopted a more careful style of combat.

7 Ernst Udet

The tragic end of Ernst Udet, the highest-scoring German ace to survive the war, is in stark contrast with the interesting life he led. After experiencing difficulty in joining the army because of his height, the Frankfurt-born Udet managed to join through the volunteer motorcyclist program at the age of 18. By 1915, he had successfully switched over to the German Air Service. Like many amateur pilots, he was first assigned to observatory duties before he was transferred to Flieger Abteilung 68, where he made his first kill in a lone attack against 22 enemy aircraft on March 18, 1916. The feat earned him the Iron Cross, First Class.

By early 1917, Flieger Abeteilung 68, now called Jasta 15, was stationed on the war front at Champagne opposite the Spork squadron, which had Georges Guynemer, France’s leading ace, in its ranks. As fate would have it, Udet came across Guynemer in one of the most prolific aerial battles of the war. The German ace had his French opponent in sight, but his gun jammed. Guynemer, realizing the unlucky plight Udet found himself in, simply waved and spared the frightened German.

Over the next year, a newly promoted Udet led different squadrons, including a flying circus, and had increased his kill count to 16. He was awarded the Pour le Merite in early 1918. After a brief sick leave, he returned to the war as the leader of Jasta 4. He had his new plane, a Fokker D VII, painted with the words Lo (to honor his girlfriend, Lola Zink) and du doch nicht (“certainly not you”) to mock Allied pilots. He brought his dogfight tally to 62 before the end of the war after an impressive spree that saw him shooting down 27 aircraft by the end of September.

After the war, Udet experienced the highest point of his life when he starred in several movies, wrote an autobiography, and featured in air shows around the world. In 1934, he made the unfortunate decision to join the Luftwaffe and slowly rose to the rank of the colonel general. Udet soon suffered a mental breakdown after he was held responsible for the loss of many of Germany’s vital air battles by Hermann Goring. On November 17, 1941, he shot himself in the head with a pistol. He was hailed as a hero by the Nazis, who claimed that he died while testing a new weapon.

6 Erich Lowenhardt

Before Erich Lowenhardt volunteered for the German air service in 1916, he had been honored with the Iron Cross, First Class, for his bravery as a member of an infantry unit a year before. After flying briefly as an observer, he was transferred to Jasta 10 in early 1917. He soon established a feared reputation among his colleagues and was made the leader of his squadron. In November 1917, Lowenhardt was lucky to escape a serious flying accident unhurt when his plane was shot down by an anti-aircraft gun. He was awarded the Pour le Merite after he’d made 24 dogfight kills by May 1918.

He engaged in a friendly ace race with Ernst Udet and Lothar von Richthofen and was appointed to lead one of the flying circuses in June 1918. By August, he became one of the only three Germans to score more than 50 aerial victories in the war. (The Red Baron and Udet were the other two.) On August 10, Lowenhardt’s plane collided with that of a fellow German, Alfred Wentz. Lowenhardt jumped out of his plane, but his parachute failed to open, which resulted in his death. Wentz survived. Lowenhardt is seen as one of the best combat fighters of World War I for his 54 dogfight victories, about half of which came in the final six weeks of his life.

5 Eduard Von Schleich

In 1908, Eduard von Schleich joined the German army through the infantry. He transferred to the air service while recuperating from a serious injury that he’d sustained in a battle in late 1914. By 1915, he joined the Feldflieger-Abteilung 2b as a pilot and was soon honored with the Iron Cross, First Class, for completing a vital mission despite his arm having been severely wounded. After recovering from the injury, von Schleich demanded and got a transfer to Jasta 21 in March 1917.

Jasta 21, which had one of the poorest combat records among German squadrons, quickly improved under von Schleich’s leadership. In July, he lost a close friend, Lieutenant Erich Limpert, in combat and ordered his plane to be painted black in Limpert’s honor. He became known as “The Black Knight,” and his squadron adopted the very cool name of “Dead Man Squadron.” In September, the Dead Man Squadron went on a killing spree, shooting down over 40 planes, 17 of which were brought down by the Black Knight himself.

After a brief sick leave, von Schleich was transferred to Jasta 32. The reason behind the reassignment was an order that only Prussians should lead Prussian units, and von Schleich was a Bavarian. In December, he was awarded the Pour le Merite after taking his kill count to 25. He briefly commanded one of the flying circuses and Jagdgruppe Number 8, a unit comprised of three Jastas (23, 32, and 35), before the armistice. Von Schleich ended the war with 35 confirmed victories despite spending barely more than a year at the front. After the war, he briefly worked with Lufthansa before joining the Luftwaffe, where he rose to the rank of general before retiring. He passed away in 1947.

4 Hans-Joachim Buddecke

In 1904, Hans-Joachim Buddecke followed in his father’s footsteps to join the US Army cadet corps. Nine years later, he moved to Indianapolis after resigning from the Army. During the next year, he worked as a mechanic and learned to fly. After war broke out in Europe, Buddecke sneaked back into Germany to join the Air Service in late 1914. He flew as an observer before he was transferred to the 23rd FFA Squadron.

Buddecke’s first dogfight victory on September 19, 1915, earned him the Iron Cross, First and Second Class, after he captured the occupants of the downed aircraft, Lieutenant W.H. Nixon and Captain J.N.S. Stott. He was soon honored with the Pour le Merite in early 1916 for playing a prominent role in the air battles of Dardanelles, Turkey, and downing his eighth aircraft. He became the third pilot, after Immelmann and Boeckle, to be awarded The Blue Max.

Buddecke was ordered back to Europe, where he first led Jasta 4 before he was to transferred Jasta 14. He was soon needed again in Turkey, where his successfully led air campaign at Gallipoli was rewarded with the Turkish Gold Liakat Medal. The Turkish soldiers who took delight in Buddecke’s flying prowess nicknamed him “El Schahin,” which means “The Hunting Falcon.” He returned once more to Europe, where he commanded different Jastas before he was killed during combat in France on March 10, 1918, at the age of 27. Buddecke was credited with 13 aerial victories before his death.

3 Werner Voss

Ask who the best German ace in World War I was, and you’re likely to be told the Red Baron. However, Werner Voss is believed by historians to be equal if not better. Voss joined the German army through the cavalry in November 1914 at the age 17. He left to join the Air Service and was soon flying as an observer before he was assigned to Jasta 2 on a temporary basis in November 1916.

His first two dogfight victories on November 27, 1916, earned him a permanent spot with Jasta 2. By May the following year, Voss had caught the attention of the Red Baron after his 28th kill had earned him the prestigious Pour le Merite in April. The Baron offered his friendship to the only man he felt could surpass him. The truth was that although Manfred was a good pilot, he was not spectacular at flying, while Voss effortlessly excelled at both. Voss was convinced by the Baron to join one of the flying circuses and claimed 14 more victories before he was killed on September 23, 1917, in one of the greatest air battles of the war.

On that day, Voss was attacked by a fleet of seven British aircraft. He managed to hold out against them for over 10 minutes before he was shot down by Arthur Rhys Davids. Voss, who had 48 dogfight victories to his name at the time of his death, was described by James McCudden as the bravest German fighter pilot he was privileged to see fight.

2 Josef Jacobs

Josef Jacobs joined the German air service in 1914. After a brief stint as a recon pilot, Jacobs achieved his first dogfight victory in February 1916, but it was declared unconfirmed due to lack of witnesses. In October, he was transferred to Jasta 22, where he subsequently took down his first confirmed aircraft on January 23, 1917. He had three confirmed kills and eight unconfirmed ones with Jasta 22 before he was moved to Jasta 7, where he was made commander on August 2, 1917.

Jacobs was awarded the Pour le Merite after downing his 24th aircraft on July 19, 1918. Still with the squadron, Josef downed 24 more aircraft between September 13 and October 27, when he won his last dogfight of the war.

Josef lived long enough to become the oldest aviation recipient of the Pour le Merite. He died in 1978. In a revealing interview about a decade before his death, Josef confessed that despite his long service with the German army and being fourth place (tied with Werner Voss) among German aces, he never received pensions because he was only a reserve officer during the war.

1 Rudolf Berthold

Rudolf Berthold joined the German army in 1909 and was transferred to the air service for observatory duties when the war began. He soon joined a fighter squadron, and by early 1916, he had already amassed five dogfight victories. Berthold soon earned a reputation as a reckless pilot who got shot down frequently. After a brief stint with Jasta 4, he was made the commander of Jasta 14 and soon won the Pour le Merite after he achieved his 12th victory. In May 1917, Berthold suffered a fractured skull, fractured pelvis, and a broken nose after his aircraft was brought down. Despite the seemingly career-ending injury, Berthold took only three months to get back to the war, although he wasn’t fully recovered.

Soon, he was chosen to lead Jasta 18, where he suffered an injury to his right arm, which rendered it useless. Berthold, who was not one to simply give up, learned to fly with just one hand. He became the leader of one of the flying circus and succeeded in downing 16 more aircraft before his war was brought to an end on August 10, 1918, when he was shot down again.

Dubbed “Iron Man” by his colleagues for his die-hard attitude, Berthold achieved 44 dogfight victories before the war ended. He was killed by rioters in 1920 at age 29, shot to death by members of the same German public he’d joined the war to protect. Some sources have falsely claimed that he was strangled to death with his own Pour le Merite medal.