Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

10 Convicts Who Shaped Australia’s Early History

As far as Europeans are concerned, life in Australia started in earnest when it was turned into a convenient place to dump criminals who would otherwise have been taking up space in British jails and breathing important European air better reserved for respectable citizens. (Never mind the Aboriginals.) So, who were these ne’er-do-well Europeans sent to Australia under sentences of transportation? They were some rather bizarre—and ultimately influential—people.

10 George Barrington

Prince Of Pickpockets

Irish-born George Barrington started down the wrong road when he stabbed a fellow student with a penknife at age 16. After that, he fell in with a group that taught him everything he’d need to know to make a living as a pickpocket and con man.

Able to mingle with the best of them, Barrington headed to London and fell in with the upper class and elite, all the while picking their pockets and stealing whatever wasn’t nailed down. His most notorious crimes included posing as a clergyman and removing the diamonds from the clothing of a member of the Knights of the Garter. His most audacious crime was trying to steal a diamond-encrusted snuff box (which would be worth several million dollars today) from a Russian count, who’d been given the treasure by Catherine the Great. Barrington was arrested fairly often but managed to either talk himself out of his sentence or get it considerably reduced. In 1790, he finally ended up at the Old Bailey, and even though he reportedly moved the jury to tears, he was sentenced to seven years’ transportation.

He disembarked in Sydney in September 1791 and spent a year laboring on a Toongabbie farm. Apparently having given up his thieving ways, he was given a conditional pardon and, perhaps strangely, was assigned work duty standing guard over crucial supplies for the new government. He was a constable by 1796, but by 1800, his life seemed to have taken another turn. Now declared officially insane, he left his post, was issued a pension, and died four years later.

That’s not quite the end of the story, however. Barrington’s name was attached to some of early British Australia’s finest historical literature. He was credited with writing The History of New South Wales, A Voyage to New South Wales, and even The Impartial and Circumstantial Narrative of the Present State of Botany Bay. The books were massive best sellers, and Barrington’s name was attached to even more publications that proved to be enduringly popular—even though he had nothing to do with actually writing them.

After all, who wants to read a dull account of some hot, dusty continent when they could read an exciting, fact-filled account of a mysterious new land told by one of the world’s finest gentleman pickpockets? A lot of the books’ facts were taken from other, legitimate sources, like journals written by others who had been a part of the First Fleet, and it mostly started with a bookseller named Henry Delahay Symonds. He’s the one who appropriated Barrington’s name and larger-than-life past and used it to create the popular image that contemporary British saw of Australia.

9 William ‘Billy’ Blue

The Old Commodore

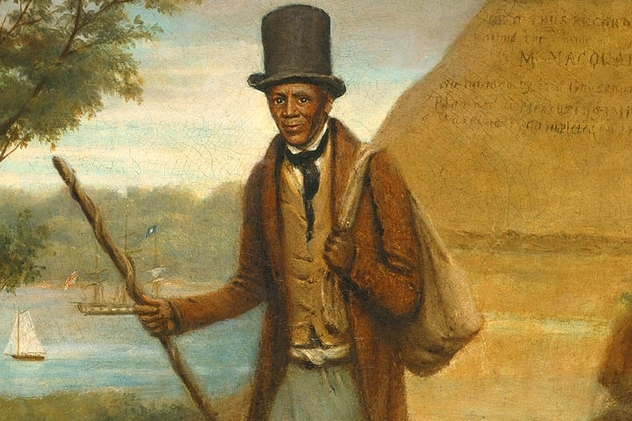

On February 24, 1829, The Australian ran a column that described what a visitor would see if they were to walk through the streets of Sydney. It highlighted all the sights and scenes, the buildings, the architecture, the shops, the signs of wilderness . . . and the presence of Billy Blue, an elderly man who brought smiles to the faces of all he met.

US-born William Blue served on the side of the British during the Revolutionary War, earning his freedom from slavery. By the mid-1790s, he was living in London and laboring as a candymaker. He was convicted of stealing sugar in October 1796. His sentence was seven years’ transportation. After serving more than four of those years on convict ships, he ended up in Sydney.

There, he met and married, worked as an oyster seller and a laborer, and later became a waterfront constable and watchman. Blue was incredibly popular with everyone who knew him and was described as “whimsical.” His home, known as Billy Blue’s Cottage, became something of a landmark, and when he was granted more land, he expanded his business to include the operation of a ferry, which quickly became a fleet of ferries. That gave him the nickname “The Old Commodore,” and it also gave him some other new opportunities. In 1818, he was convicted of smuggling rum. Even though he claimed that he’d simply found the rum floating in the water, he was sentenced to a year in prison, and his titles were taken away.

By the time Blue got out, a couple of others were trying to move in on his ferry service. He appealed to the government for the right to run his ferry, and he won. After his wife’s death, he grew more and more eccentric, often wearing the remnants of an old naval uniform and boarding ships to act as the official welcoming party for those who’d just arrived. He continued to have his issues with the law, once found harboring a fugitive and once barely avoiding prison when he was found guilty of killing a boy who had been tormenting him. Blue had thrown a rock at the boy.

Blue died in 1834, leaving behind a legacy of amusing anecdotes. Several streets in Sydney are named for him, along with his old ferry terminus, which is still in use. Portraits of him still hang in libraries throughout Sydney, solidifying his position as one of Australia’s most eccentric convicts.

8 Isaac Nichols

Postmaster-Thief

Born in England in 1770, Isaac Nichols had quite a record when it came to breaking the law, and a 1790 conviction for stealing would earn him the popular sentence of seven years’ transportation to New South Wales. When his sentence was served, he was granted some land, where he oversaw some of the convicts serving out their own sentences. Only two years later, he was in court again, this time on the charge of receiving stolen property. Even though he was found guilty, several members of the trial believed that he was innocent and that the evidence against him was perjury. They referred the matter to the higher English court, and a few years later, Nichols was granted a full pardon.

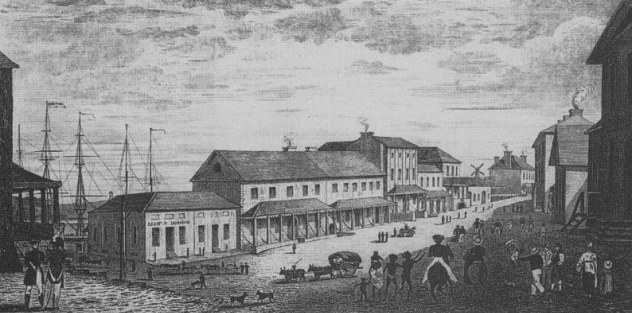

In the meantime, there were some rebellions and reorganizations of the social structure, with Nichols finding himself appointed assistant to the naval officer and a superintendent of public works. It was around 1809 when he decided that he wanted to do something about the mail system—or lack thereof—in Australia. There was little in place to keep people from claiming mail that wasn’t theirs, so Nichols went on to set up the first post office.

Nichols ran the post out of his own house, which was on George Street in Sydney (pictured above). When the mail came in, he’d run the names of all the recipients in The Sydney Gazette, letting them know they’d received something. It was up to them to pick up the mail—and pay him his handling fee of one shilling. Packages cost more, and if the mail was for a person of significant importance, Nichols would deliver it personally. He retired in 1814 and died in 1819. Upon his death, Nichols was remembered by The Gazette not only for his contributions to the realm of public service, but also for the advancements he made in the areas of Australian gardening.

7 Daniel Herbert

Rogue Stonemason

Born in 1802, Daniel Herbert’s crimes were severe enough to earn him a death sentence. In 1827, he was accused and found guilty of highway robbery. Part of what made that crime so particularly severe was the “fear and danger” that went along with it. He’d already been convicted of breaking into a home and stealing, and when he and his accomplices pleaded guilty, they were sentenced to death. That was changed to exile in Australia for life, and he was dropped off in Hobart Town in December 1827.

Herbert was assigned to the Engineer’s Department and made frequent appearances before the magistrate for unapproved work absences and drunkenness. In 1835, he was assigned to work on a bridge that’s since become one of the most enigmatic structures from the era. The Ross Bridge in Tasmania was nominated by Engineering Heritage Tasmania as a national landmark, largely because of the ornate carvings that Herbert created. From a distance, it’s a rather unassuming, small bridge, made of three arches that stretch across the river. It’s a different story up close.

The arches’ stones were carved with a series of Celtic designs and caricatures, most likely of people whom Herbert knew. Historians have combed other areas of 17th- and 18th-century architecture to find anything else in the world like them, to no avail. Also odd is the complete lack of correspondence when it came to approvals for the carvings. According to all of the official literature and documentation, they were just building a bridge. Even the overseer’s journals and inspector’s reports say nothing of the carvings, which are on every stone in the arch. Carving the keystone might have been more typical, but Herbert’s work on the Ross Bridge still stands out as one of the finest examples of convict labor and art from the era.

Engineering Heritage Tasmania put forward the idea that the carvings were done with the approval of Captain William Turner, who saw the project not just as a bridge that needed to be built, but as a venue for stonemason convicts to express themselves, reaffirm their humanity, and leave something beautiful behind.

6 Richard Browne

Convict Artist

If you’ve seen any pieces of early art depicting the Aboriginals, you’ve probably seen Richard Browne’s work. It’s considered one of the best examples not just of art from the time, but of depictions that make the relationship between the newly arrived Europeans and the Aboriginals quite clear.

We only know a bit about Browne. He was born in Dublin in 1771 and was around 40 years old when he was sentenced to exile in Australia. His exact crime isn’t known, but it’s thought to have had something to do with forgery. He arrived on Australian shores in 1811 and was soon before the courts again, ultimately moved to the secondary penal colony in Newcastle. He started painting there, and his work appeared most famously in a manuscript called “Select Specimens From Nature of the Birds and Animals of New South Wales,” giving Europeans their first glimpse at some of the most exotic species that Australia had to offer. One of Newcastle’s commanding officers recognized Browne’s talent and interest in art and natural history and kick-started his artistic career.

Browne served out his Newcastle sentence and was released in 1817, when he headed to Sydney and started to sell his watercolors. His most in-demand work was of Aboriginals depicted in their natural environments and dress, usually with weapons and almost always with a sort of caricature-like quality that went a long way in supporting the British image of the native peoples. (An example is shown above.) Browne’s work seemed to be designed to give Europeans both in Australia and back home a reason to want to “civilize” the natives, bring them into the cities (so they could have their hunting grounds), and try to make them more European. His portraits were also used as support for pseudoscientists of the day, giving phrenologists the ammunition they needed to declare that the Aboriginals were a lesser species.

5 Zephaniah Williams

Chartist And Coal Baron

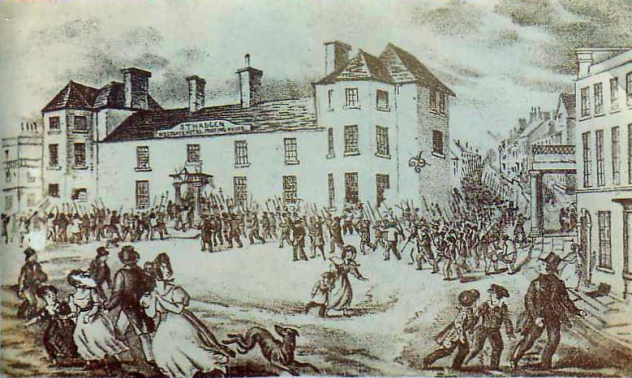

In the 1830s, the Chartist movement was getting into full swing, demanding a more equal standing for the working-class people of Britain. Industrialization had come to Wales, and it brought with it cholera, typhus, and increasingly dangerous working conditions. Workers had little to no rights, and by the end of the decade, they’d had enough. On November 4, 1839, an armed uprising (pictured above) at the Westgate Hotel in Monmouthshire left 22 dead and countless others wounded. At the head of the uprising were three middle-class leaders—tailor and ex-mayor John Frost, actor and watchmaker William Jones, and geologist and miner Zephaniah Williams. The three were found guilty of treason. Although that carried a death sentence, they were instead sentenced to transportation, largely due to fear of further uprising if they were hanged. By 1840, they were in Hobart, and from there, Williams was taken to Port Arthur.

Assigned to Port Arthur’s fledgling coal mining operation, Williams soon put his background as a miner and geologist to good use, and after a failed escape attempt that rewarded him with 16 weeks of solitary confinement, he developed a method of making iron castings. After entering the grounds of an insane asylum that was in the middle of riot and defusing the situation, he gained a little bit more freedom. After another failed escape attempt and another sentence, he turned again to coal mining.

After working the Triumph mine, Williams eventually struck out on his own and formed a company that would revolutionize mining in Australia. With over 2,000 acres under his control, he built camps, tramways, and homes for miners, bringing in many of his employees from England and Wales. Before Williams and the Triumph mine, there had been a monopoly on coal production in Australia, just the sort of thing that the Chartist rebels protested back in Wales. Williams received his free pardon in 1857 and chose to remain in Tasmania—not a bad choice for a man who had once faced the prospect of being hanged, drawn, and quartered.

4 John Knatchbull

Moral Insanity

A new land is a chance for a new criminal justice system, and English-born John Knatchbull was just the person to help Australia define an acceptable defense for murder. Probably born in 1793, he was the son of a man who’d married three times and had somewhere around 20 children. He joined the navy, where he retired without a pension, as it was used to pay off debts he’d incurred while in service. In 1824, he was arrested under a false name (John Fitch) and convicted of “stealing with force and arms.” His 14-year transportation sentence started in 1825, where he was installed in the police system.

Knatchbull’s experiences there were rather checkered. He gained kudos for arresting some runaways, but he was also found guilty of check forgery and handed a death sentence that was changed to seven years’ transportation on Norfolk Island. On the way there, he acted as a double agent in putting down a mutiny that ended with his partial paralysis and 29 mutineers sentenced to death. They named Knatchbull as their chief mutineer.

After that, he was shipped back to Sydney to serve the rest of his original sentence, and in 1844, he was arrested yet again. This time, it was for the murder of and elderly widow named Ellen Jamieson, and he confessed his guilt. His defense was one of moral insanity, and it was just as bizarre as his life has been so far. That same year, he had also proposed to a young girl, reported in the papers as having the unlikely name of “Mrs. Craig.” As the wedding approached, he found himself owing £5 for rent and £6 for a wedding dress. Clearly, the only way he was going to raise that kind of money was to kill Mrs. Jamieson, a shopkeeper.

Knatchbull’s defense claimed that while he was otherwise in possession of his mental faculties, he was clearly insane—but just morally. The careless manner of the murder was the only evidence offered in support of the case, and he was found guilty. When the verdict was handed out, he claimed that the Devil made him do it. It was the first time that anyone had ever tried to use the moral insanity defense, giving the British court the chance to set a precedent. They did—by denying it. Knatchbull then tried to appeal based on the judge’s neglect in specifying that his body be dissected after he was dead. When that didn’t work, either, he was hanged on February 13.

3 Sir Henry Browne Hayes

Fun And Freemasonry

Irish-born Henry Bronwe Hayes made several key contributions to early Australian history, including founding the first Masonic lodge there. Whether or not he actually had permission and the authority to do so is up for debate, but the meeting that he held on May 14, 1803, is regarded as the founding of the Freemasons in Australia. He’s also known for building Vaucluse House, which was turned into a national monument and was once the home of W.C. Wentworth. The snake-free property (which Hayes surrounded with turf from Ireland as a surprisingly successful reptile repellent) was bought by the Australian government in 1910 as a memorial to Wentworth.

Before all of that, however, Hayes found himself shipped to Australia after a series of strange events that no rational person would consider a good idea. Originally a captain in the South Cork Militia, Hayes became a sheriff and was even knighted in 1790. By 1797, he was a widower, and with a few children to support, he decided that the only viable solution was to kidnap a Quaker heiress named Mary Pike and force her to marry him. The wedding happened, but Pike’s family came to her aid and put a bounty on Hayes’s head. He went into hiding, and by “went into hiding,” we mean that he waited three years before turning himself in for trial. Contrary to what he’d apparently believed, the heat hadn’t died down much, and he was found guilty and given a death sentence.

The death sentence was changed to a life sentence in Australia, and Hayes arrived in New South Wales in 1802. After paying for privileges during the trip, he immediately ended up in jail for harassing the ship’s surgeon. He was linked to an uprising a few years later in 1804, after he successfully founded the roots of Freemasonry in Australia. Once he’d served his exile sentence for his (alleged) part in the uprising, his rebel views got him another stint in exile, this time in the coal mines of Newcastle. Miraculously, he was finally pardoned in 1809, returned to Ireland in 1812, and died in 1832.

2 Thomas Griffiths Wainewright

Poisoner, Forger, Portrait Painter

Born in 1794 and raised by his grandfather, Thomas Griffiths Wainewright moved in the same circles as the likes of William Blake and Mary Wollstonecraft. It’s no wonder that he ended up developing skill that would define art in colonial Australia and leave us with portraits of many of the most important names in Australia’s early history. Of course, the road to Australia was often a pretty rocky one.

Wainewright knew luxury from an early age, and by the time he married in 1817, he was living well beyond his means. He already had a career in art, with his work being exhibited at the Royal Academy, so in order to solve his financial problems, he put his artistic talent to work in another way—forging signatures. These weren’t just any signatures; they were carefully chosen ones that would allow him to inherit the money that he needed to maintain his lifestyle.

It all came crumbling down when three family members—an uncle, a sister-in-law, and a mother-in-law—all died under rather suspicious circumstances, all conveniently leaving money to him. When the uncle died, Wainewright inherited the family estate. The scheme involving Helen Abercrombie, his wife’s healthy, young half-sister, was even more telling. Wainewright took out an insurance policy on her, and she died shortly after. After her death, he legged it off to France for a little over five years, which isn’t suspicious in the least. His actions finally caught up to him when he was arrested during an 1837 visit to London, and while the court couldn’t find anything that directly tied him to his family members’ deaths, they did discover his forgery.

That was enough to get him a life’s transportation sentence, and he ended up in Tasmania, then called Van Diemen’s Land. He was first assigned to a road gang and then to a hospital, where he started to paint portraits. Beginning with the people he met in the hospital, his fame as a portrait artist grew, and he did portraits of everyone from other settlers and pioneers to a lieutenant-governor and business entrepreneurs. Those paintings are now in national portrait galleries around the world, immortalizing some of the key players in Australia’s development.

Tracing the man, however, is a bit more difficult. When he went to Australia, his wife and son left for the US, his belongings were sold, and most of his early work disappeared. Wainewright became even more notorious than his deeds would suggest, used by both Oscar Wilde and Charles Dickens (who even paid him a visit once) to describe what villainy is.

1 Laurence Hynes Halloran

Bigamist Preacher, Public School Founder

The problem with writing about Laurence Hynes Halloran is knowing where to start.

In 1825, a petition was submitted to the Australian government and all appropriate councils. It called for the establishment of the Public Free Grammar School in Sydney, and it was authored by Laurence Halloran, DD, professor of the classics and of mathematics. He began by saying that he wanted nothing more than to afford the minds of Sydney with the opportunities that went along with education, and the kindness he’d found in Sydney had encouraged him to pay something back to this wonderful community.

It was a community that Halloran reached after a rather complicated series of events. An Irishman born in 1765, he was an orphan who joined the navy and was first jailed for the stabbing death of another midshipman in 1783. He was acquitted the next year, and he moved to Exeter to marry and to run a school, presumably because background checks hadn’t been invented yet. Charged with “immorality” in 1796, he tried to become an ordained minister and failed. That didn’t stop him from reentering the navy as a chaplain, though, and he was installed with a group at the Cape of Good Hope. After running afoul of the commanding general, he decided that the best way to deal with the situation was to publish a series of false claims regarding the whole thing. He was, unsurprisingly, found guilty, returned to Europe, and set about on a lifestyle dependent on his abilities as a forger. Finally convicted on the charge of forging a tenpenny frank, he was shipped to Sydney.

There, he established his first school, and the story wasn’t over yet. Separated from his first wife but reunited with his other family (which included some children and their mother, who was also likely Halloran’s own niece), he kept on writing and kept getting buried in defamation suits. Financial ruin followed, and it was only after he served a prison sentence for debt that he petitioned for the founding of the above-mentioned public school.

That school opened in November 1825, and in a March 1826 edition of The Sydney Gazette, some of the plan’s shortcomings were outlined. Halloran was accused of constant drunkenness and an addiction to swearing, and students told stories about fighting and his perpetual drunkenness. By October, the school’s operation was suspended, but with Halloran conveniently in jail once again by November, the school embarked on a do-over. Once out of jail, Halloran opened his own newspaper, which could only loosely be called a newspaper, as it was known for publishing two things—articles by Halloran and reports on the libel suits issued against him.

When that business failed, he was briefly appointed as Sydney’s coroner but was removed from that position when he threatened to start publishing still more articles about an archdeacon. He died not long after that in 1831, presumably having never learned his own lessons.