Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

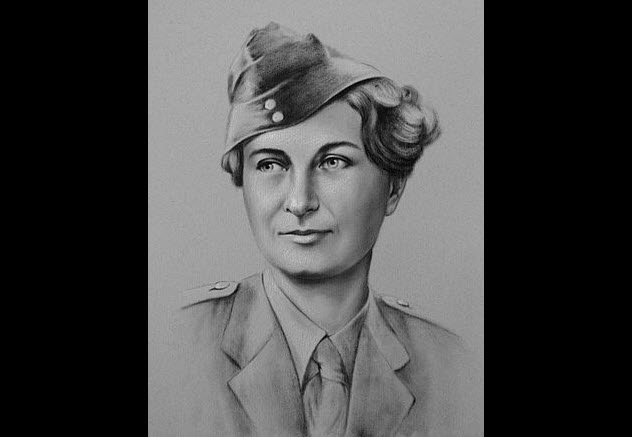

10 Incredible Stories From The Most Badass Woman In World War II

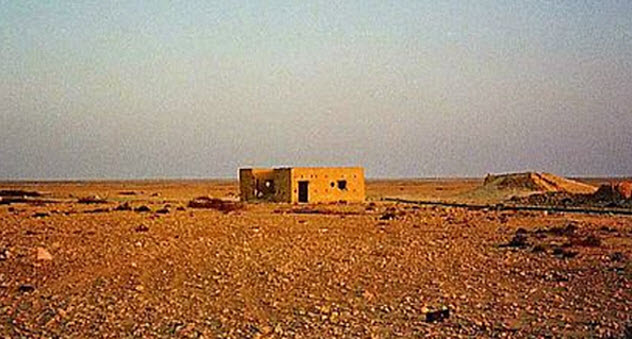

Nothing but sand, rocks, and despair surround Bir Hakeim, a desolate outpost in the Libyan desert. In May 1942, 3,500 Free French legionnaires committed themselves to one of the most extraordinary acts of bravery seen this side of mythology. For two weeks, they holed up in Bir Hakeim while tens of thousands of German and Italian troops with panzers and air support rained hellfire around them.

The Battle of Bir Hakeim is now considered one of the greatest sieges of the African war. Although the battle took place a continent away, it became a symbol of defiance and courage for the scattered Resistance clinging to the embers of life in occupied France. Despair that had gripped French souls with steel hooks was shaken off, and hope finally emerged from its long slumber. In no small part, it was thanks to a British socialite named Susan Travers.

10The Socialite

Susan Travers was born in England in 1909 with a silver spoon shoved down her throat. From the time she first opened her blue eyes as an infant, she never wanted for anything. Her father was rich, her mother was richer, and the marriage was acrimonious at the best of times.

As a young girl, Susan was surely loved but largely ignored. Her father had been promoted to admiral in the Royal Navy, which brought the strict brand of discipline that soldiers often carry from the barracks into their own homes. According to her memoirs, Susan’s happiest moments in childhood were spent with her grandmother, away from her parents.

While Susan was still young, her father moved their family to the French Riviera to be closer to his new naval posting in Marseilles. As she transitioned from child to adult in the Mediterranean climate of southern France, Susan began spending more time away from home. She attended parties, went on skiing trips in the Alps, and learned tennis, as all the other fashionable women of the time were doing. She even competed at Wimbledon once.

Glamorous though her life was, it left a sour taste in Susan’s mouth. It was too tame. She wanted adventure, sex, and danger. “Most of all, I wanted to be wicked,” she said later. And in this universe, some wishes are granted. Even as she dreamed of a life more perilous, Hitler’s forces in the north were assembling like a storm cloud to bring all the danger that Susan could have hoped for.

9The Red Cross

When World War II broke out, Susan was 29 years old. Her family had moved back to England, but she was still enjoying the Cannes high life on a monthly allowance. She’d grown into a beautiful, high-spirited woman with an appetite to match, leaving her free to reject as many potential suitors as she took.

In her own words, life was “parties and champagne, and tangos and Charlestons, Vienna and Budapest and all sorts of places. I had lots and lots of friends. Lots and lots of young men. Well, lovers, really.” Her father, disapproving as always, once called her une fille facile—basically, a slut. Life was fun but increasingly empty.

When the papers announced the war, Susan jumped at the chance to do something more with her life. Like so many women at the time, she volunteered for the Red Cross. But Susan was a terrible nurse. She’d lived her whole life on tennis courts and ski slopes, and the sight of blood made her squeamish. She switched to driving ambulances, an occupation that suited her freewheeling spirit much better.

Susan soon found herself en route to Finland to ferry wounded soldiers off the battlefield. The Finnish Winter War was a bleak period, but Susan used it to hone her ability to drive under pressure, a skill that later saved the lives of thousands of men.

She was still in Scandinavia in 1940 when the French government signed an armistice granting Germany control of the country. With that single act, Susan’s old life disappeared in the blink of an eye. There was no going back. She was now a part of this war, for better or for worse.

8The Driver

After the fall of France, Susan worked her way circuitously back to London. The French government had been split asunder, but there was still one man fighting to bring France back under the control of the French—General Charles de Gaulle. He had fled occupied France and set up his headquarters in England. There, he commanded the remains of the French military forces who were still loyal to his ideals of freedom. His army became known as the Free French.

Susan Travers found de Gaulle in London and volunteered to help the Resistance. The Free French were desperate for whatever help they could get, and Susan was immediately put to work as a nurse. In August 1940, she sailed to West Africa on a ship filled with rough-and-tumble Free French legionnaires.

For nearly a year, she went wherever she was needed. From Cameroon to the Congo and from Sudan to Eritrea, she mopped up gallons of blood and tended to the needs of dying men.

By June 1941, Susan was again desperate for change, so she volunteered to drive for a doctor while serving in the Middle East. To her surprise, her offer was accepted. Life was finally more exciting. When her doctor died by a land mine, she was assigned to another doctor.

Quickly, her reputation grew among the fighting men. She was a woman who refused no assignment. She would grit her teeth, clench the wheel, and drive straight through a minefield if it lay between her and where she needed to go. More than once, she arrived at her destination with bomb shrapnel embedded in her vehicle.

The legionnaires began to call her “La Miss,” an honorary title for the plucky Englishwoman who never backed down. As Trisha McFarland would have said, Susan had ice running through her veins—she never lost her cool. Then, on June 17, 1941, a man got blown up in a fruit garden, forever changing Susan Travers’s life.

7The General

June 1941 found Susan Travers in Beirut, just another sandy, war-torn city in a long line that never seemed to end. On the Western Front, Britain was still shell-shocked by the devastation of the blitzkrieg. In the East, Minsk was in ruins, and the German Wehrmacht was rolling deeper into Soviet territory. The war seemed interminable, the deaths endless.

It’s possible, though, that the brutality of war has provided as many lovers as it’s taken. Susan certainly found that to be true. While in Beirut, General Marie-Pierre Koenig of the Free French lost his driver to a bomb. La Miss was the next obvious choice. By that time in the war, General Koenig was one of the most respected officers of the legionnaires, so he required an equally respected chauffeur.

They took to each other immediately and soon became lovers. Since Koenig was married, they carried on their affair in secret. When Susan was bedridden in the hospital with jaundice, General Koenig brought flowers to her bedside and assured her that her job would be waiting for her when she got better. Even well after the war when Susan was in her nineties, she remembered her time with the general more fondly than any other period in World War II, perhaps even in her whole life.

But her cautiously built dreams of a life with General Koenig came crashing down at Bir Hakeim.

6The Fort

Bir Hakeim was originally constructed in the 16th or 17th century during the reign of the Ottoman Empire. Built from rusty sandstone plucked from the surrounding desert, Bir Hakeim gives the appearance of having slowly risen from the landscape of its own accord, imbued with the begrudging sentience of an old and tired god. It’s a guardian of sand and howling winds, the kind of outpost where men were stationed to disappear from the sanity of civilization.

Italy had taken a turn at building up Bir Hakeim after gaining control of the territory in the aftermath of the Italo-Turkish War in 1912. But the desert is a lonely place to die, and the fortress was largely abandoned in the years to follow.

As winter faded in early 1942, the Allies were in dire straits in northern Africa. They’d been caught by surprise by General Erwin Rommel in Benghazi, leading to an Allied retreat along the Libyan coast.

Somehow, they’d managed to regroup and form a defensive line, known as the Gazala Line, between the coastal city of Gazala and Bir Hakeim, 80 kilometers (50 mi) south of the coast. The line was marked by “boxes,” fortified outposts from which the Allies hoped to repel the German attack. Playing red rover with the Axis, the Allies hoped that wherever they were attacked, the line would hold.

5The Brigade

In the swirl of preparation along the Gazala Line, General Koenig was ordered to Bir Hakeim. As his personal driver, Susan dutifully followed. Time was short—intel held that an attack on the line was imminent—and the Gazala Line at the time was no stronger than an idea.

Worse, when Koenig and the Free French arrived at Bir Hakeim, they found that their predecessors hadn’t finished the job of fortifying the outpost. With less than 4,000 men at his disposal, Koenig went to work.

For the next three months, the Free French dug in. They surrounded the Bir Hakeim with an array of V-shaped minefields that pointed away from the central position. They dug hundreds of foxholes, trenches, and underground shelters.

In less than 12 weeks, they turned the bare desert surrounding the crumbling fortress into a death trap. Travers helped wherever she could, ferrying workers and carting supplies around the work area.

As the circle of death grew complete, however, the same question weighed on everyone’s mind: Would it be enough?

4The Desert Fox

While the Frenchmen toiled under the unforgiving sun in the Libyan Desert, a fox prowled just out of sight. General Erwin Rommel, newly appointed commander of the Afrika Corps, was marching East with 320 German tanks that were reinforced by another 240 Italian tanks. No stranger to African warfare, Rommel had been nicknamed “The Desert Fox” by journalists, and he carried the name proudly.

Rommel had spent the preceding months gathering his strength, but he knew that the British were doing the same. He needed to attack fast and hard before the defensive line got any stronger if he was going to have any hope of eventually taking Egypt and the vital supply lines afforded by the Suez Canal.

At the end of May 1942, Rommel approached Gazala with the full force of the 21st and 15th Panzer Divisions. All along the Gazala Line, soldiers hunkered down for the fighting to come. Nobody knew where he was going to attack the line.

But Rommel had no intention of playing a child’s game. He marched straight to the center of the line and engaged the British troops before making a show of moving north, hoping to draw most of the defenders with him.

It was all a trick. Under cover of nightfall, Rommel turned and led his army south. His plan was to flank the southern end of the Gazala Line and move north behind the Allied defenses, cutting off the army’s head by severing its supply lines.

The only thing that stood in his way was the tiny, undermanned Bir Hakeim outpost. It was going to be easy.

3The Siege

May 27, 1942, dawned hot and dry over Bir Hakeim. Colonel Koenig had ordered all the women at the fort to be evacuated days earlier, but Susan Travers had refused to leave, telling him, “Wherever you will go, I will go, too.”

As a result, she was the only woman in the fort when Rommel’s first probing attacks landed. Besides her, there were 3,700 men left to defend Bir Hakeim. But the Desert Fox was attacking with seven times that number.

Rommel sent an armored Italian division to make the first attack on Bir Hakeim. At this point, he fully expected to burn through the fort “in 15 minutes.” To everyone’s surprise, the Free French sent the Italian force running with their tails between their legs. Forty Italian tanks were left behind, destroyed by mines and French artillery.

Rommel was incensed. He sent Koenig an ultimatum: Surrender or be destroyed. Koenig replied, “We are not here to surrender.”

For two grueling weeks, the 1st Free French Brigade traded bullets with the Germans and withstood the massive barrage of tank fire. Rommel called in wave after wave of bombers to gut the fort, but the French persevered with suicidal tenacity. Susan Travers spent the entire siege in a foxhole sweating in the intense heat and waiting for the right bomb to fall that would blow her to pieces.

Finally, though, the French reached their limit. By the second week of June, they were out of food, ammunition, and most importantly, water. By their own design, they’d boxed themselves in with layer upon layer of trip wires and mines. They had to surrender or die. Koenig, however, saw a third option: They were going to break out of their self-constructed prison.

2The Escape

Escape from Bir Hakeim was a difficult proposition: They were surrounded by thousands of mines, and the Germans had encircled the fort with three concentric ranks of panzers.

Nevertheless, Koenig arranged the mission. They left in the dead of night, departing quietly in a line of vehicles just before midnight on June 10. Susan was driving Koenig’s car near the front, and all was going well until one of their trucks struck a land mine.

The night caught fire around them. Rommel quickly zeroed in on the would-be escapees and ordered his men to fire at will. Tracer rounds streaked through the black night, highlighting their position for the heavy artillery.

Escape had been a gamble, a suicide charge. While vehicles and soldiers were blown to bits by tanks and land mines, Susan Travers finally got the chance to experience her brief moment of destiny. Over the roar of the tank shells, Koenig told Susan, “If we go, the rest will follow.”

So Susan went. She maneuvered into the front of the train of vehicles and floored it, blasting past panzers with mere meters to spare. She swerved around mines and bomb craters. Her reckless charge opened a hole in the German dragnet, allowing more vehicles to follow in her wake.

It’s estimated that she was responsible for the escape of almost 2,500 soldiers. By the time she reached safety, her vehicle had nearly a dozen bullet holes and chunks of shrapnel embedded in the metal.

1The Legionnaire

All too often, love is as much a force of sorrow as of joy. Although Susan had risked her life to stay with Koenig, their affair wasn’t meant to last. He was, after all, a married man. After Bir Hakeim, Koenig’s wife joined him in Africa. Susan only saw him once after that, a decade later.

Susan spiraled into depression and contemplated suicide, but her indomitable spirit won out as always. In May 1945, she applied to the French Foreign Legion and was accepted, becoming the only female to serve as a legionnaire. She even sewed her own uniform because the legion didn’t have any designed for a woman.

Susan Travers eventually married and settled down. In 1956, she was awarded the Medaille Militaire for her actions at Bir Hakeim. The man who pinned the medal to her lapel was none other than Pierre Koenig. She never saw him again. Susan Travers died in 2003.

Eli Nixon is the author of Son of Tesla and its sequel, Mind of Tesla.