Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Momentous Events That Also Occurred on July 4th

Animals

Animals 10 Times Desperate Animals Asked People for Help… and Got It

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Music Biopics That Actually Got It Right

History

History 10 Momentous Events That Also Occurred on July 4th

Animals

Animals 10 Times Desperate Animals Asked People for Help… and Got It

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

10 More Of The Most Important Works Written In Prison

Following from this great list, here are 10 more of the greatest works ever written in prison. It seems that some of the most influential literature in our history has been penned during the author’s imprisonment. Many of the books mentioned below—in no special order—are written by political or religious prisoners who would go on to transform their nation as statesmen or secure immortality through their writing. There is far more to prison literature than Mein Kampf folks!

10 A Hymn To The Pillory br>

Daniel Defoe

Contempt, that false New Word for shame,

Is without Crime, an empty Name.

A Shadow to Amuse Mankind,

But never frights the Wise or Well-fix’d Mind.

Daniel Defoe (1660–1731) is best known to us today for his novel Robinson Crusoe, but he spent most of his life as a campaigner and pamphleteer during the tumultuous political and religious tension following England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688.

In 1702, Defoe anonymously published The Shortest Way with the Dissenters, which satirized High Anglican Tories during the reign of Queen Anne who were intolerant of Protestant nonconformists such as Defoe. In it, he imitated their persona and proposed that instead of passing any laws against religious dissenters, it would be more expedient to simply kill them all.

At first, many Anglican Tories took the proposal seriously, but soon Defoe’s authorship was discovered and in 1703, he was arrested for seditious libel. Defoe was then sentenced to “stand in the pillory three times, to pay a fine of 200 marks, and to remain in Newgate until he could find sureties of his good behaviour for seven years.”

In Newgate Prison, Defoe composed A Hymn to the Pillory, which was sold in the streets during one of his sessions in the pillory. The poem is believed to have won the crowd over to such an extent that instead of pelting him with rotten food and cutting his ears off, as was the fate of a Puritan dissenter a few weeks prior, spectators decorated his pillory with flowers. A biographer of Defoe later said that “no man in England but Defoe ever stood in the pillory and later rose to eminence among his fellow men.”

9 The Pilgrim’s Progress br>

John Bunyan

The lifelong Puritan John Bunyan fought for the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War, and after the monarchy was restored with the reign of Charles II, he was sentenced to 12 years in prison for refusing to stop preaching his non-conformist message. In prison, Bunyan completed his autobiography Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners in 1666 and set to work on The Pilgrim’s Progress, a hugely popular Christian allegory published in 1678.

Fully titled The Pilgrim’s Progress from This World to That Which Is to Come; Delivered under the Similitude of a Dream, the book follows the protagonist, Christian, on a journey from the decadent “City of Destruction” (Earth) to the “Celestial City” (Heaven). The second part of the book follows Christian’s wife, imaginatively named Christiana, on a similar journey based on Protestant theology.

8 The Age Of Reason br>

Thomas Paine

Once called “a corset maker by trade, a journalist by profession, and a propagandist by inclination,” Thomas Paine (1737–1809) featured prominently in the two greatest political achievements of the Age of Enlightenment: the American Revolution and the French Revolution.

After playing a crucial role in the American Revolution with his “Common Sense” political pamphlet, the English-born Paine was convicted of seditious libel against the British government after defending the French Revolution in Rights of Man (1791). He fled to France, where he soon found himself elected to the French National Convention—despite not speaking French!—as an ally to the Girondists and enemy to the more radical Montagnards, led by Maximilien Robespierre. As the Reign of Terror ensued, Paine was taken prisoner in Paris by order of Robespierre, then president of the Committee of Public Safety.

In prison, Paine continued to write his latest work, The Age of Reason, which challenged the authority of organized religion and advocated for deism. Paine miraculously avoided execution long enough to be released after the fall of Robespierre and returned to America on Jefferson’s invitation.

7 The 120 Days Of Sodom, Or The School Of Libertinism br>

Marquis de Sade

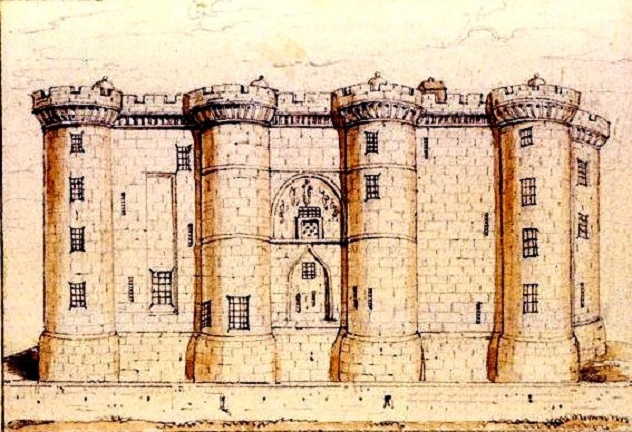

The 120 Days of Sodom was written in just 37 days on a 12-meter-long (40 ft) roll of paper by the French nobleman Donatien Alphonse Francois, Marquis de Sade.

The novel was written in 1785 during Sade’s imprisonment in the Bastille (pictured above). When the Bastille was stormed four years later, the work was taken, and Sade later wrote that he “wept tears of blood” at the loss of the manuscript. He lived the rest of his life not knowing what happened to it, dying in 1814. The work was eventually found and published in 1905.

The unfinished novel, which Sade himself called “the most impure tale that has ever been told since our world began,” spans five months, telling the story of four noblemen who hide themselves away in a remote medieval castle with 50 victims, whom they use to play out their fantasies and fetishes.

The men indulge in every kind of depravity with girls and boys as young as 12, according to four successive passions—simple, complex, criminal, and murderous. The original piece has since sold for millions of euros, and the terms “sadism” and “masochism” are derived from his name.

6 Discovery Of India br>

Jawaharlal Nehru

“India has known the innocence and insouciance of childhood, the passion and abandon of youth, and the ripe wisdom of maturity that comes from long experience of pain and pleasure; and over and over a gain she has renewed her childhood and youth and age.”

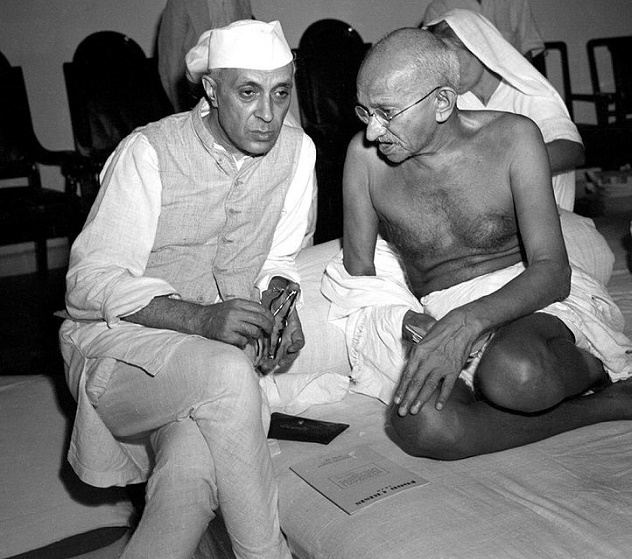

If Mahatma Gandhi is the Father of India, then Jawaharlal Nehru is the nation’s greatest son. Under Gandhi’s mentorship, Jawaharlal Nehru was a prominent leader in the Indian Independence movement, which began the partition of India and the end of the British Raj in 1947.

But in the years leading up to independence, Nehru was taken as a political prisoner for his involvement in the Quit India movement. He wrote The Discovery of India during his imprisonment in 1942–46, with contributions from fellow political prisoners in Ahmednagar fort.

The book takes the reader through much of the history, culture, and philosophy of India, with the author covering nearly every aspect of Indian life before arguing that India has a right to sovereignty.

Jawaharlal Nehru served as the newly sovereign country’s first prime minister until his death in 1964. The Discovery of India is one of India’s most beloved books, giving the reader an extensive insight into the worldview of the statesman who, more than any other, defined modern-day India.

5 Introduction To Mathematical Philosophy br>

Bertrand Russell

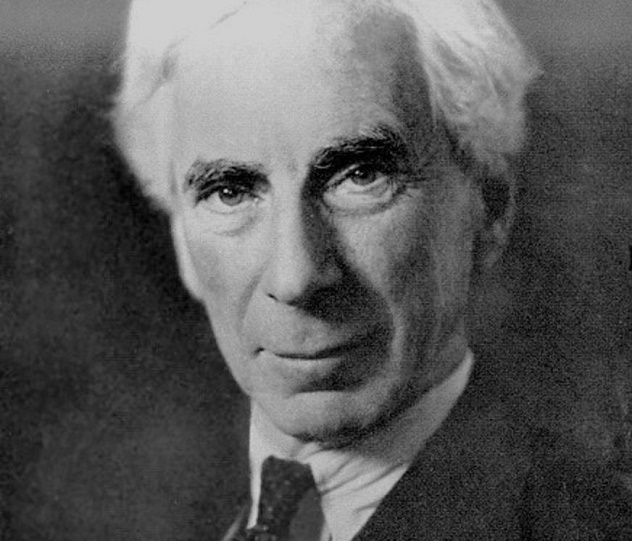

“I found prison in many ways quite agreeable. I had no engagements, no difficult decisions to make, no fear of callers, no interruptions to my work.” (From The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell)

Bertrand Russell was a lifelong pacifist, and went to prison as a conscientious objector during World War I. Russell spent most of his six-month sentence writing Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy, a book expounding on the ideas laid out in his three-volume work Principia Mathematica (co-written with Alfred North Whitehead), which argued that mathematics and logic had become so intertwined that “they differ as boy and man: logic is the youth of mathematics and mathematics is the manhood of logic.”

Russell is remembered as one of the 20th century’s foremost intellectuals and won the 1950 Nobel Prize for Literature “in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought.”

4 Don Quixote br>

Miguel de Cervantes

“Do you see over yonder, friend Sancho, thirty or forty hulking giants? I intend to do battle with them and slay them.”

Miguel de Cervantes (1547–1616) writes in the prologue to Don Quixote that the epic tale was “begotten in a prison.” The great work, originally titled The Ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote of La Mancha, was partially written during Cervantes’s imprisonment for failing to pay his debts. This is ironic, since the Spaniard had earlier served as bookkeeper and tax collector for the Spanish crown after a distinguished military career.

The partnership between the novel’s protagonist, Don Quixote, a knight errant who is inspired by great stories of the past to right wrongs across Spain, and his faithful squire, Sancho Panza, who tries to correct his master’s outlandish fantasies, is one of the most iconic in all of literature. The title character is also the origin of the adjective “quixotic,” meaning “extremely idealistic and impractical.”

Published in two parts, the first in 1605 and the second in 1615, Don Quixote is now regarded as one of the first European novels and the greatest piece of literature ever conceived by an accountant.

3 ‘Infelix Ego’ br>

Girolamo Savonarola

The Dominican Friar Girolamo Savonarola (1452–1498) was the de facto ruler of Florence in the five years leading up to his gruesome death. During his leadership, Savonarola spoke of Christian renewal in Renaissance Florence and waged a puritanical campaign against Pope Alexander VI. After rejecting partnership with the Pope’s Holy League, Savonarola was summoned to Rome. He was excommunicated by the pope in 1497 after denouncing the Vatican’s corruption, and he was jailed for preaching blasphemy against the church.

Savonarola was tortured on the rack until he confessed that he had invented his visions and prophecies for a reformed Christendom. They left his right arm intact so he could sign the confession. He was burned at the stake in the Piazza della Signoria two weeks later.

During his imprisonment, Savonarola composed “Infelix Ego,” known in English as “Alas, wretch that I am,” a meditation on Psalm 51 to beg forgiveness from God for recanting his deeply held beliefs after torture. It begins:

“Alas, wretch that I am, destitute of all help, who have offended heaven and earth — where shall I go? Whither shall I turn myself? To whom shall I fly? Who will take pity on me? To heaven I dare not lift up my eyes, for I have deeply sinned against it; on earth I find no refuge, for I have been an offence to it. What therefore shall I do? Shall I despair? Far from it. God is merciful, my Saviour is loving. God alone therefore is my refuge.”

Heavy stuff.

Savonarola’s causes for republican freedom and religious reform were still espoused by his devotees, though progress was painstakingly slow. All told, Girolamo Savonarola’s life is a tragic story of an enlightened campaigner broken by man’s inhumanity to man.

2 On The Law Of War And Peace br>

Hugo Grotius

“By understanding many things, I have accomplished nothing.” These are believed to be the last words of Hugo Grotius, the Dutch scholar, statesman, and political theorist best remembered for his pioneering work in the field of international law. His treatise De jure belli ac pacis (On the Law of War and Peace to me and you) has secured his place in history.

Born in 1583, Grotius rose to become attorney general of Holland in his mid-twenties and pensionary (similar to a state governor) of Rotterdam by 1613, where he was tasked with settling disputes between rival European navies. He was an early advocate of freedom of the seas, but the British—the dominant power at the time—thought otherwise. Grotius also espoused religious tolerance in his homeland, which would lead to his life imprisonment after being on the wrong side of a coup d’etat carried out by Maurice of Orange. However, he managed to escape prison and flee to Paris by hiding inside a large case that the guards thought were filled with books.

But it was in the years of imprisonment (1918–1921) that Grotius started writing On the Law of War and Peace. In three volumes, Grotius argued that there are situations in which wars are just wars: when a nation is acting in self-defence or when seeking reparations and revenge. He then outlined an early 17th century playbook for warring nations, with chapter titles such as What is Lawful in War and On the Right of Embassies adorning its pages.

A key theme Grotius developed was that nation-states were subject to natural law, which he thought came from God, since Nature was God’s creation. Grotius wrote that these laws would hold true “even if we should concede that which cannot be conceded without the utmost wickedness, that there is no God, or that the affairs of men are of no concern to Him.”

Because of this treatise, Grotius is considered one of the intellectual fathers of international law. He spent the rest of his life traveling around Europe and survived a shipwreck in 1645, before dying later that year. Not such an uneventful life after all.

1 The Long Walk To Freedom br>

Nelson Mandela

“No one is born hating another person because of the colour of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.”

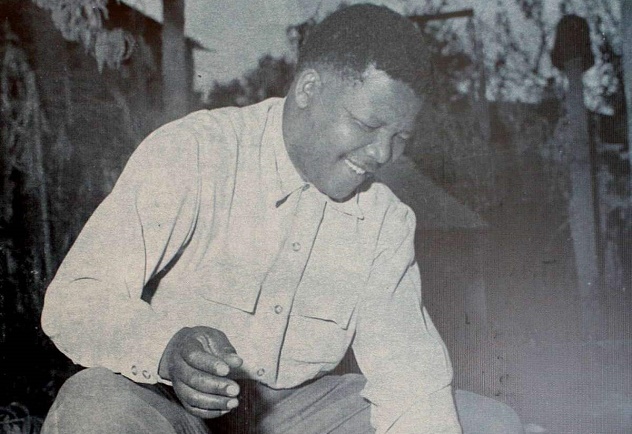

Nelson Mandela’s 1990 release from prison is a moment many will never forget. Regarded as a terrorist for his leadership of the African National Congress (ANC) and held in captivity for 27 years, Mandela put an end to white minority rule and strict racial segregation in South Africa. He won the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize, together with Frederik Willem de Klerk, for peacefully ending apartheid and forming a new democratic South Africa, which he led as First President of South Africa for five years.

Mandela’s 1995 autobiography recounts his early life, education, and experiences in prison, particularly the 18 years spent on Robben Island, where he was made to do hard labor in a lime quarry, repeatedly locked in solitary confinement, and held in a damp concrete cell with a straw mat for a bed. Much of the autobiography is based on the manuscript Mandela wrote in prison.

Long Walk To Freedom went on to become one of the best-selling political memoirs of all time, and Mandela will forever be remembered as the father figure of post-apartheid South Africa. Nelson Mandela died in 2013.

I love to read and write, and never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity.

![Top 10 Most Important Nude Scenes In Movie History [Videos] Top 10 Most Important Nude Scenes In Movie History [Videos]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/sharonstone-150x150.jpg)