Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

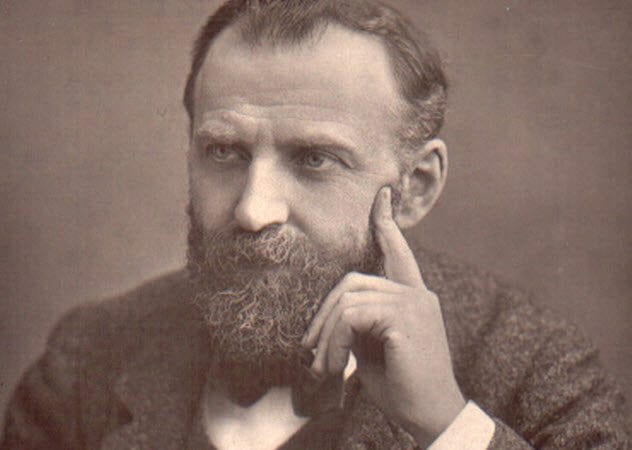

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

10 Ridiculous Things The Victorians Did In The Name Of Science

The words “Victorian science” bring to mind sober men with ridiculous facial hair peering through microscopes. What it doesn’t bring to mind are certifiable lunatics trying to fly into space, electrocute their genitals, and teach dogs the alphabet. Yet that’s exactly what researchers of the day were up to.

10 Trying To Take A Hot Air Balloon Into Space

If scientist James Glaisher had had his way, the first manned spaceflight would have taken place 100 years before Yuri Gagarin’s. That’s because 1862 was the year that Glaisher and Henry Coxwell set off in their hot air balloon for the “aerial ocean” above. Their government-funded flight took off from Wolverhampton on September 5. Almost immediately, things went horribly wrong.

Approximately 8 kilometers (5 mi) above the Earth, the temperatures dropped to -20 degrees Celsius (-4 °F) and the animals that Glaisher had brought to observe died. About 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) above that, both men suddenly got the bends and collapsed.

At 11 kilometers (7 mi) up, both men blacked out but not before Coxwell pulled the valve release cord with his teeth. To Glaisher’s dismay, the balloon descended, taking them away from the edges of the atmosphere.

Somehow, this near-death experience didn’t put Glaisher off. He made 21 more flights but never realized his dream of ballooning into space.

9 Interviewing Politicians Telepathically

As editor of The Pall Mall Gazette, W.T. Stead championed anything that would help us talk to one another. However, he didn’t discriminate between real-world stuff and ideas from la-la land. Stead was convinced that he could talk to people using only the power of his mind.

At the time, many believed in hidden psychic abilities. So it seemed plausible that you might be able to contact people mentally. For Stead, this meant telepathically sending notes to his secretary, dictating reports to his writers while in another country, and trying to ask questions of famous politicians using only his mind.

Indeed, Stead’s greatest “scoop” came thanks to his powers. He was one of the people killed on the Titanic in 1912. His journalists later claimed that he telepathically reported the disaster to them as it happened.

8 Teaching Dogs To Read

Sir John Lubbock was one of Victorian Britain’s leading scientists. Over his long career, he invented the words “Neolithic” and “Paleolithic,” became vice chancellor of London University, and introduced Thomas Edison’s electric streetlights to England. Oh, and he also wasted hundreds of research hours trying to teach his dog to read.

Lubbock was convinced that dogs could be taught to understand English. Not just simple commands like “sit,” “stay,” or “come back with my donut,” but full, complex sentences. To that end, he drew up giant boards with sentences on them, stuck them in front of his dog, and tried to get the animal to understand them.

By his own account, Lubbock insisted he’d scientifically proven that dogs were capable of learning to read. However, no one has ever repeated this feat.

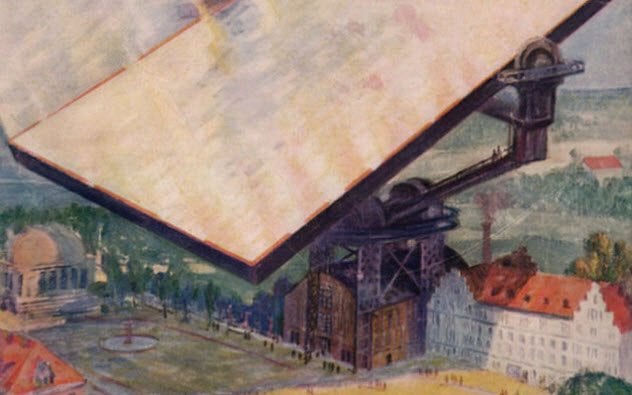

7 Communicating With Mars

In 1888, Giovanni Schiaparelli announced the discovery of canali on Mars. In Italian, canali means “channels.” A translation mistake meant the English-speaking public heard of them as “canals,” implying intelligence. Almost immediately, this sparked a craze for communicating with Martians through any means possible.

One of the maddest attempts came in 1892. A wealthy French woman had bequeathed an absurd amount of money to establish a network of giant mirrors across Earth. These mirrors would be flashed at the red planet, sending Morse code messages hurtling across the empty depths of space. The Martians would see these messages, build similar mirrors, and flash their own messages back.

By 1892, preparations were well underway to begin using the mirrors to communicate with Mars. Unfortunately, the plan fell apart when more sober scientists pointed out that Mars was now moving away from Earth so the aliens wouldn’t see them anyway.

6 Testing Spectacles On Horses

In 1893, an unsuspecting horse owner sparked one of science’s most bizarre quests. Convinced that his horse was going blind, the anonymous man walked into an optician’s store and ordered a pair of horse glasses. For optician Mr. Dolland, it was the start of a lifelong quest to provide horses with spectacles.

Dolland became convinced that all horses were shortsighted. They bolted when something spooked them because they couldn’t see what it really was. Design a pair of perfect horse specs and bolting, with its attendant injuries, would be a thing of the past.

It’s unknown how long Dolland kept at his crazy idea, but it was certainly long enough to test different glasses on dozens of horses. Eventually, he settled on a pair of bifocals he believed could improve the sight of any horse in the world. The horse-owning public disagreed. Dolland’s contribution to equine science sank without a trace.

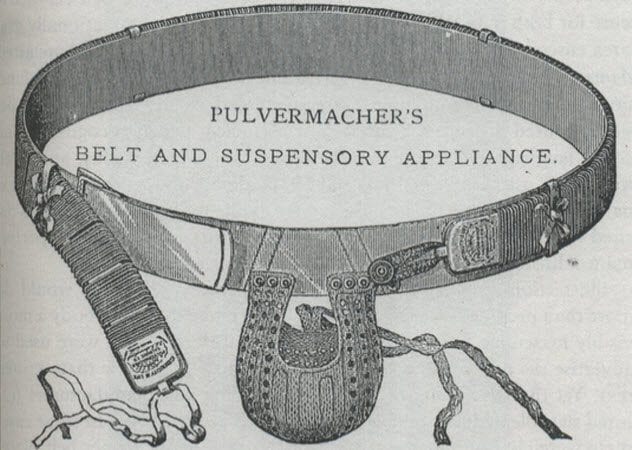

5 Electrocuting Their Own Genitals

The Victorians liked men to be men, and any sign of unmanliness was a serious cause of concern. To battle weakness and deficiencies of “masculine energy,” Victorian scientists came up with one of the most absurd cures ever: a belt that delivered constant electric shocks to the subject’s genitals.

These were the days when electricity was so new that it was considered a potential cure-all for just about everything. Just as wackos in the 1950s claimed that radiation could heal anything, so too did Victorians consider electricity a kind of wonder drug.

The experiments were considered such a success that their use expanded to curing impotence, and they started appearing for sale in magazines. Strangely enough, they never really caught on with the general public, who seemed unwilling to embrace severe shocks to their genitalia.

4 Training Wasps As Pets

Remember John Lubbock, the guy who thought he could teach dogs to read? Turns out he had a second hobby that was nearly as weird as the first. Lubbock was convinced that you could train wasps to be the perfect pet.

He tried to train them like you would a dog—to eat out of his hand, allow themselves to be stroked, accompany him to meetings, and, presumably, attack his enemies on command.

As you’d expect, these experiments didn’t go well. Lubbock frequently got stung by his tiny charges, who we’re gonna assume failed to understand what the heck was going on. Yet he persevered and, amazingly, managed to train one single wasp to obey his commands. The creature only lasted nine months before dying, but that was enough for Lubbock to proclaim the winged monsters made perfect pets.

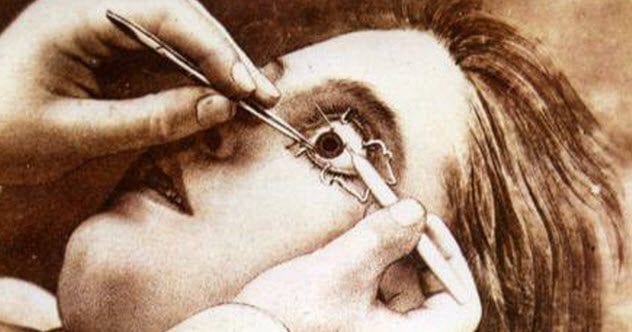

3 Imprinting On The Eyes Of Condemned Criminals

Optography is the practice of analyzing the eyeball to reproduce the last image it saw. If that sounds nuts, it’s because it is. Not that this stopped the Victorians from trying. From 1880 onward, scores of condemned men were asked by scientists to look at dramatic things just before they were executed.

Wilhelm Kuhne led the charge. In 1880, he acquired the head of guillotined murderer Erhard Gustav Reif and examined his eyeballs for images of violent movement. As time went on, the experiments became more elaborate. One condemned man was asked to keep his eyes completely shut as he was led onto the scaffold and to snap them open the second before he was hanged. Strangely, he acquiesced.

Such experiments were so numerous that optography acquired a respectable sheen. As late as 1927, murderers destroyed their victims’ eyeballs to prevent identification by optography.

2 Insane Self-Experiments

The Victorian era saw the emergence of medical ethics. For the first time, you couldn’t just grab a pauper to conduct your experiments on. This meant loads of scientists conducted experiments on the only available people: themselves and their associates. Some of these experiments were insane.

Take August Bier’s investigations into spinal anesthesia. In 1898, the German surgeon and his assistant Augustus Hildebrandt shot their spines full of cocaine and tried to discover if they could still feel pain. Hildebrandt punched a hole in his boss’s neck, leaving spinal fluid leaking out. Meanwhile, Bier stabbed, clubbed, and burned his partner before crushing his testicles. When neither felt any pain, they celebrated by getting riotously drunk.

Others did equally bad stuff. Jesse Lazear allowed himself to be bitten by mosquitoes carrying yellow fever, while Pierre Curie brought Victorian craziness into the Edwardian era by deliberately giving himself radiation burns.

1 Eating One Of Everything In Existence

William Buckland has many claims to fame. He was a theologian, a geologist, and one of the only people Charles Darwin actively hated. But we’re only interested in his strangest experiment. At some point in his life, Buckland decided it would be useful if he ate one of everything in existence and recorded its taste for future generations.

In the name of “science,” Buckland located and devoured everything from mice on toast to alligators to bat urine to puppies. He dined on potted ostrich, roast hedgehog, panthers, porpoises, and even the preserved heart of King Louis XIV. He’s been called “the man who ate everything.” And he recorded the taste of each item meticulously.

Incredibly, in his lifelong experiment, Buckland only found one creature that he didn’t enjoy eating. According to his notes, the common garden mole tasted “disgusting.”