Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

10 Ancient Reconstructions You Have To See To Believe

Throwing around theories can only get the experts so far. For the more hands-on type of researcher, nothing beats being able to recreate something from history, bringing back to life the machines, words, technology, and even foods that sustained our ancestors. Recreations can link the past with the present, and sometimes, the knowledge that returns can be breathtaking.

10Skull Surgery

The 2015 discovery of a Siberian skull allowed doctors to replicate ancient brain surgery. The 3,000-year-old head came with a carved hole. Closer inspection painted a clearer picture of the operation, known as trepanation.

Researchers even tried the techniques on fresh skulls. First, the patient had to be sedated, likely with a mind-altering plant. The angle of the wound’s edges indicate that the man rested on his back, head turned to the right. The surgeon would’ve cut down to the bone while an assistant opened the skin. After tissue layers were folded away, a hole was scraped down to the brain.

Too much bleeding could be fatal, so the Bronze Age medics had to move with expert speed before replacing and securing the scalp. New bone growth proved the man lived afterward, but signs of a persistent post-operative inflammation hinted he never survived the recovery period.

9The Pyramid Machine

Within the Great Pyramid of Giza is a primitive machine. It might not excite hardcore engineers, but it was sophisticated for its time.

To protect the king’s body, ancient masons created a system to seal off the burial room. Its presence was known since the 19th century, but with the help of a digital recreation, Egyptologists could see it in action for the first time. Three mammoth granite slabs hung inside the walls just outside the king’s chamber, where scholars believe Pharaoh Khufu’s mummy once rested. A series of grooves moved the blocks down a chute and provided a formidable barrier against grave robbers by blocking the inner sanctum. It was looted anyway.

More optimistic Egyptologists believe the room was a decoy and that the real tomb of Khufu might be found behind three unexplored doors located deeply down small shafts.

8The Mother Tongue

Most languages today evolved from Proto-Indo-European, or PIE. Spoken by a culture that populated the plains to the northern area of the Caspian Sea, the language existed between 6,000–3,500 BC. Extensive studies on daughter languages put some of its vocabulary back together, but for centuries, experts accepted that the sounds of PIE would never be heard again.

Then the cool cookies at Cambridge and Oxford Universities resurrected the extinct speech. They developed a way to flip a spoken word’s sound into numbers. When compared to other words with the same meaning in PIE-related languages today or earlier versions, researchers could gauge how vocals changed over time by studying how the numbers changed. Shape was turned back into sound, and PIE began to emerge. It’s a work in progress, but certain words are being spoken again for the for time in 8,000 years.

7The Real Psittacosaurus

Dinosaur resurrections aren’t new, but one from China is the most accurate ever done. Resembling a strange toy, it’s cute and somewhat creepy. When discovered, the turkey-sized Psittasaur fossil came with exquisite detail, including skin and pigment. Recreating its muscles and color revealed a wealth of information and a rare look at a real dinosaur free of artistic guesswork.

The boxy face sported horned cheeks and a parrot mouth. The tail carried a bristled Mohawk. The 100-million-year-old herbivore walked on its back legs, had good eyesight, and the large head—which surprised those involved in the reconstruction—indicated high intelligence. Pigmentation was also unexpectedly abundant. Colored scales on the limbs, shoulders, skin flaps and cloaca suited an animal hiding in the shade, perhaps beneath a forest canopy. As such, it’s the first solid evidence of camouflage in a terrestrial fossil.

6Colosseum Killing Machine

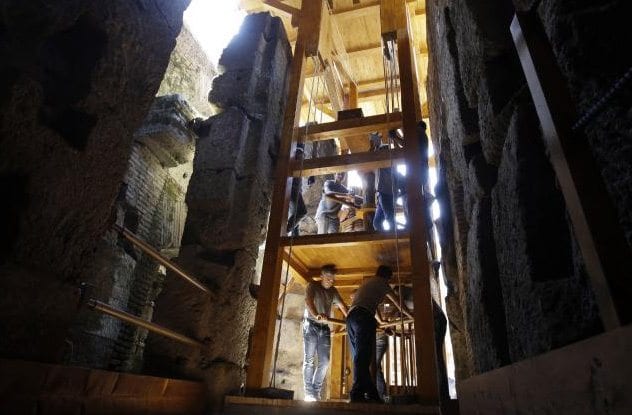

When released into the Colosseum, animals didn’t traipse up the stairs. A giant wooden cage, working like an ancient elevator, hoisted wild creatures up to the arena where they fought to the death. A project was launched to return this feature as a permanent part of the Colosseum.

Researchers teased details regarding its design and the complex rope and pulley system from underneath the arena. Below, tunnels revealed bronze fittings, carved openings for timber posts and rope chafing against stone left clues to the system’s directional movements. Once hammered together, it was capable of lifting up to 300 kilograms and required eight men to operate. When the replicated elevator was tested, it carried an adult male wolf into the amphitheater. He became the first animal to trot out into the Colosseum in 1,500 years.

Instead of meeting a bloody fate, the wolf was treated with a biscuit.

5Stone Age Superglue

Toolmakers achieved something remarkable 70,000 years ago. They devised a superglue that kept instruments from falling apart. Acacia tree gum was mixed with red ochre, and the pigment was thought to be merely decorative. That was before researchers cooked up a batch using only materials and techniques from the Stone Age. They discovered the iron-rich ocher put the super in glue.

The mixture sounds simple, but for this ancient community, who lived in what is today South Africa, it wasn’t easy to produce an adhesive that worked. There is a chemical balance that is responsible for making the glue so potent. They didn’t know about pH or iron content yet produced goo that clung with a vengeance. They knew certain trees, types of gum, and different ochre sites combined best for the desired results. This suggests Stone Age intelligence and technology was more advanced than generally accepted.

4Egyptian Furnace

A few years before the reign of Tutankhamen, experts thought that the decoration-loving Egyptians imported their glass from the Near East. The discovery of a 3,000-year-old furnace proved this historical assumption to be wrong. They not only made their own but were also advanced glass makers.

At the ruins of an industrial complex against the Nile, at Armarna, a team of archaeologists built a replica of the furnace. Using local sand, they soon produced glass. It went so well that it’s even possible the Egyptians used a mere single-step process. While in operation, the complex provided work space for other highly skilled craftsmen besides the glass makers. Pottery, blue pigment, and faience were also produced at the high temperature facilities.

3Pompeii’s Wine

The AD 79 eruption of Vesuvius buried most of Pompeii’s wine farms under ash. In the 1800s, casts were made of the grapevines and their remaining supports.

Curious to taste wine once described as the Roman Empire’s best, archaeologists and winemakers got together. They studied the casts and old frescoes to determine the grape variety and identified two types still grown near Vesuvius. Surviving farming manuals and vine trellis provided information on cultivation. Originally, Pompeii vines were packed closely together, and researchers feared the harvest would suffer because of it, but the fertile Pompeii soil worked wonders. Modern fermentation techniques were chosen since the Romans made their wine under unhygienic conditions. Laced with a hideous taste, the strong alcoholic punch was probably behind its popularity.

Fifteen of Pompeii’s vineyards have been restored, and the wine, called Villa dei Misteri, now appears in elite restaurants around the world.

2Underwater Concrete

Early Roman architects erected Caesarea Harbor in the Mediterranean Sea. It was one of the greatest engineering feats of its time, and modern archaeologists wanted to recreate the incredible hydraulic concrete piers poured beneath the waves 2,000 years ago.

The writings of ancient architect Pollio Vitruvius identified the ingredients as lime, sand, volcanic rocks, and seawater. Vitruvius didn’t explain how to secure to the seabed the wooden forms needed to shape the concrete, nor how to mix the mortar aggregate or pour it.

The casing was recreated by studying plank imprints from similar concrete sites. After mixing the cement, mortar was tipped in using a basket system copied from old construction drawings. The aggregate was added by hand as the building progressed. In 2004, after 273 hours of manual labor and 13 tons of material, three archaeologists successfully raised a “pila,” a Roman free-standing pier, from the bottom of the sea.

1Damascus Steel

When metallurgists from Stanford University discussed their latest invention, they realized they may have unwittingly rediscovered the manufacturing process for the legendary Damascus steel.

A sword hobbyist attending the meeting mentioned that their “superplastic” metal, like Damascus steel, had a high carbon content. Further analysis delivered fantastic results—the two metals owned near-identical properties.

Known for swirling patterns and formidable blades, the historic swords were valued throughout the ancient world and was the weapon used by the Crusaders in the 11th century. Two things contributed to the loss of Damascus blades. Blacksmiths kept their knowledge secret, and firearms arrived.

Both steel varieties are warmed at moderate temperatures, reheated, and then rapidly cooled down with fluids. This creates carbide grains. In Damascus steel, they are responsible for the hardiness and beautiful surface lines. Contemporary technology creates tinier grains, making the superplastic metal more workable and harder that Damascus steel.