History

History  History

History  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

10 Fascinating Discoveries About The Anasazi

Also known as the Anasazi, the ancestral Pueblos were a prehistoric Native American nation. They left behind breathtaking buildings and mysterious graves. Extensive research has been done on this Pre-Columbian society that originated around 1200 BC, and some of it yielded remarkable genetic information, exposing the true power players, advanced knowledge, and trade routes. Scientists even met the more human side of the people who stretched throughout the Four Corners of the United States.

10They Made Beer

Many Native American groups mastered beer-making in antiquity. Southwestern Pueblos was thought to have hung on to their sobriety until the 16th-century arrival of the Spanish, who brought grapes. Recently, 800-year-old pottery shards were examined. They belonged to the Pueblos who historians had believed stayed dry, while other tribes consumed a weak corn beer called tiswin.

This didn’t make sense to archaeologist Glenna Dean. Refusing to believe that this New Mexico group could be so isolated and out of touch with neighboring tribes, she took the shards to Sandia National Laboratories. There, she received access to scanning technologies usually reserved for national defense. Dean also tested pots used by modern Tarahumara groups to brew tiswin and vessels in which she brewed her own.

All three samples showed the same residue commonly created during beer fermentation. Despite the similarities, it cannot be said for certain the shards came from a pot of intentionally fermented kernels. Even so, it’s the first evidence that this “sober society” had their fun too.

9The Corn Was Imported

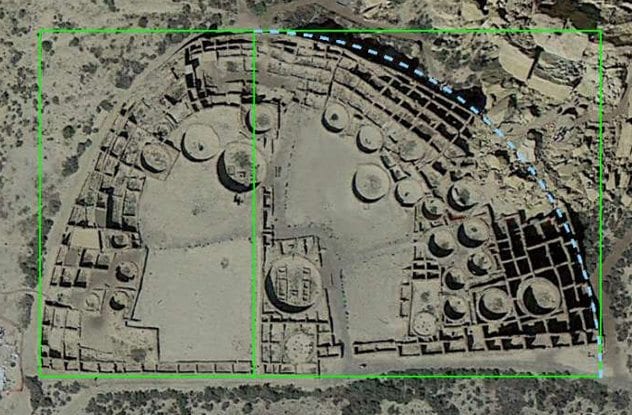

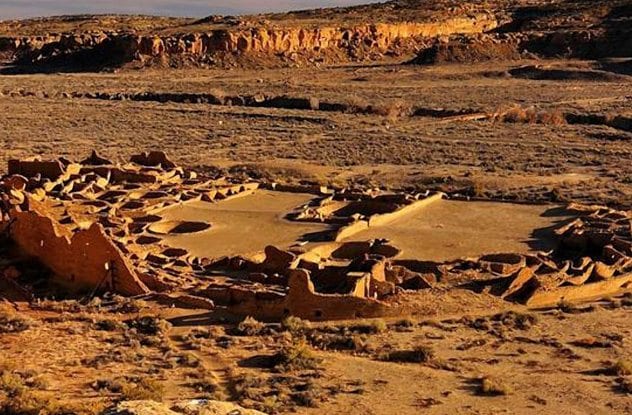

By the time 1100 rolled around, a couple of thousand people lived in Chaco Canyon. They were at their cultural zenith and had political power over a vast area. Yet, they lived on land too salty to grow staple foods such as corn and beans. The quality of the soil prevented these crops from producing enough to feed the masses, and tree ring studies showed that there wasn’t enough rain. Either few people lived in the valley or corn was imported. Scientists believed the second was more likely.

Ancient ruins indicate that not only did a large population live at Chaco but roads linked them with other Pueblo communities. One of these was a settlement 50 miles to the west. Hugging the eastern flank of the Chuska Mountains, they had the water to raise corn in abundance. There’s no direct evidence this was Chaco’s corn supplier, but the two groups are known to have traded other items, so the idea is not so far-fetched. What researchers cannot understand is why anybody wanted to live in the harsh Chaco Canyon.

8Far View Reservoir

A new study changed the purpose of an ancient Pueblo structure in Colorado. Thought to be a water reservoir, the 1,000-year-old sandstone pit was shown to be really bad at the job. In 1917, one naturalist decided it was built to store water, and the idea stuck. Its name also reflects this, when it was decided to officially call it the Far View Reservoir. The location was wrong.

The Pueblos were knowledgeable about the land, building, and keeping water. The structure, which measures 90 feet (27.5 meters) across and 22 feet (6.65 meters) deep, sits on a ridge, which isn’t optimal at all. Past researchers theorized about a “now missing” gathering basin connected to the less elevated reservoir. The more recent study dispelled that notion.

The pit is connected to several ancient structures via ditches, but these are too shallow to transfer water effectively. Climate models showed it couldn’t have collected rainwater sufficiently either. The reservoir resembles Pueblo architecture found elsewhere, including a great kiva, ball court, and amphitheater. The ditches were likely ceremonial, much like Chacoan ceremony roads.

7Living Status Symbols

In 1897, 30 macaw skeletons were found in Chaco Canyon. More specifically, inside Pueblo Bonito, the biggest of the stately, multistoried homes. The exotic tropical birds are changing what experts know about when the Puebloans first developed more evolved social and economic behaviors.

Scarlet Macaws, imported from Mesoamerica, were highly valued. Adorning ritual artifacts and clothing, their red feathers had religious and symbolic importance. When the bones were dated more recently, they were far older than they should be. Initially, it was believed that Chaco Canyon’s rise as a cultural and religious center spawned the ability to trade with far off places, allowing for more economic growth.

Their golden age lasted from 1040–1140 CE. From 14 Macaws, 12 predate this time, with seven going as far back as the year 800. This means that long-distance trade started centuries earlier than believed and influenced a more complex culture and an elite hierarchy who would’ve controlled the ownership and trade of the birds.

6Timber Harvests

Chaco Canyon’s houses have been called “monumental” with good reason. Some of the biggest pre-Columbian buildings belong to the settlement. Pueblo Bonito, where the Macaw remains were found, was once five stories tall and boasted around 500 rooms. It was made of stone and wooden beams, and archaeologists wondered from where the desert nation got their timber. Trees and weather provided the answer.

Each location’s weather is different and uniquely influences a region’s tree growth rings. Analyzing some 6,000 wood specimens from Chaco Canyon, two mountain ranges were identified for the first time. Before 1020, timber was harvested 50 miles (75 km) to the south from the Zuni Mountains. By 1060, the Chuska Mountains about 50 miles (75 km) to the west supplied the wood. The swap happened at the same time the Chacoans experienced a big shift. They changed their masonry techniques and increased construction as their culture boomed. In the end, about 240,000 trees were used to create the mammoth buildings.

5Turquoise Trade

What diamonds represent today, turquoise did for the ancient Pueblo Indians. Their love of the blue-green mineral apparently knew no bounds. Over 200,000 pieces were found in Chaco Canyon alone.

Initially, it was believed that Chaco got all its gems from a nearby mine and imported some more. A closer chemical look determined that only the elites living in Pueblo Bonito used a nearby mine and possibly kept the location a secret. This didn’t hamper the Pueblo on the street. The turquoise network was a remarkable trading effort that existed across Colorado, Nevada, and southeastern California. When pieces from Nevada were tested, they busted another belief that the flow existed just for the benefit of the canyon residents. The Nevada turquoise originated in Colorado and New Mexico, hinting that the network was more of a two-way affair than exclusive importing to Chaco Canyon.

4Room 33

Inside Pueblo Bonito are more skeletons. The chamber, known as Room 33, received the bodies of 14 individuals over 330 years (800–1130). A wealth of artifacts support the belief that these men and women belonged to the elite who ruled Pueblo society, their power spanning hundreds of miles. It’s uncommon to find so many in a crypt in the Southwest.

This made researchers curious about their relationships to each other. Testing for family ties, they focused on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). The findings were so surprising that the team thought the samples had been contaminated. Renewed testing showed that the results were correct.

These people were all family with identical mtDNA, descending from a single female ancestor. There’s still no clear view of how Chacoan society was structured. This valuable discovery adds an elite family who controlled Chaco Canyon for centuries, showed power was hereditary through the matrilineal lineage and that they were likely behind the rise of this remarkable society.

3Advanced Geometry

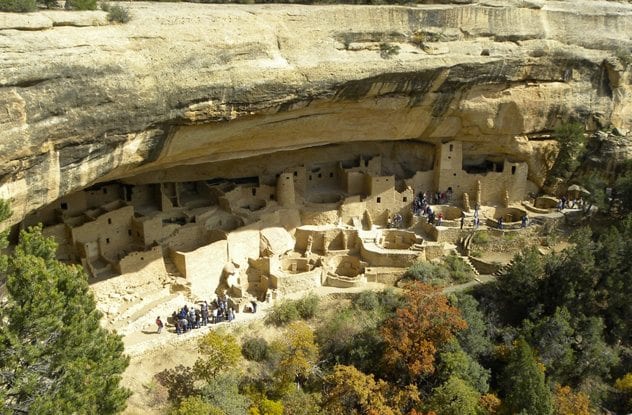

Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park is home to the Sun Temple. The archaeological site was built around 1200. The Southwestern Pueblos used it for ceremonies and solstice tracking. During a study to see if the observatory was used to watch stars as well, something unexpected happened. The same measurements and patterns began to reveal themselves in the Temple’s architecture.

Near-perfect squares and different types of triangles repeated at key points across the site, including equilateral triangles, 45-degree right triangles, and Pythagorean triangles. Incredibly, even the “Golden rectangle” showed up. The latter was a favorite of ancient Greek and Egyptian architects. The common unit of measurement at the Temple was 30 centimeters (around 1 foot). What makes this a near-genius endeavor is that the Pueblos had no system for numbers or a written language. Yet, they mastered advanced geometry. Today, that would be the same as trying to design and build a house without numbers or records.

2Blue J

When archaeologists found a Pueblo village lacking key traits, they thought they had found a rebel colony. There were no multistoried homes crucial for trade and ritual, no underground kivas for elites to gather during meetings and ceremonies. Nicknamed “Blue J,” the settlement lies 70 kilometers south from the heartbeat of Pueblo culture, Chaco Canyon. The distinct lack of form proposed that the residents of Blue J didn’t play well with the power center and refused to follow certain traditions.

The 11th-century settlement consisted of around 60 households and plazas. Decades passed before new technology, in the form of a remote-controlled drone, revealed different scenery. Its infrared scans found structures hidden beneath the desert floor. The subterranean ruins included a courtyard facing large rooms, walls and two huge, deep circular shapes consistent with ceremonial kivas. One showed the perfect dimensions for a kiva and this could change everything. A religious building at Blue J would mean the village conformed with Chaco Canyon’s influence.

1Why They Vanished

When the ancestral Pueblo nation disappeared, they did so without any clear reason. It remains one of archaeology’s greatest puzzles. A new study might pin it on a series of droughts.

Scientists gathered information from over 1,000 sites related to the Pueblos and 30,000 tree ring dates. Together, they produced an incredible year-by-year view of the region’s weather. Across the board, a recurrent cycle of drought could be seen. Each time, it coincided with major changes within the prehistoric society. If researchers are right, the Pueblos’ fate was sealed centuries before their culture petered out.

During a span of 500 years (700–1250), four dry periods occurred, and the worst hit last. Each time, the destruction of crops instigated civil inequality, unrest, and violence. Belief systems and rituals changed to deal with the crisis. The weather data and social changes with every drought indicates that the Puebloan vanishing act was merely a cultural transition and eventual abandonment of their trademark traditions and sites.