History

History  History

History  Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

Top 10 Logical Fallacies We Abuse When We Argue Online

So you’ve gotten into an argument on the internet.

Don’t worry. What’s happening to you right now is completely natural, and it’s nothing to be ashamed about. People calling strangers twats is one of the cornerstones of the internet; a proud tradition without which many a site’s comment section would be a barren wasteland.

10 Simple But Costly Math Errors In History

Arguing on the internet could even be a good thing. This could be an opportunity for you to hear other people’s point-of-views and really understand the world from a different perspective. All it takes is a little dignity and a focus on the facts.

That’s why we’ve prepared a list of logical fallacies we want you to avoid when you argue online. Because, so far, most of the biggest arguments on the internet have fallen right into these traps.

Just because you’re pooping and typing curse words with your thumbs doesn’t mean you can’t show a little decorum.

10 Appeal to Authority

One of the oldest arguments on the internet is the great debate over how to pronounce “GIF”.

From the day the first dancing baby appeared on a Geocities site, people on the internet have been fighting over whether to pronounce it with a hard G, like “good”, or with a soft G, like a heathen.

But in 2013, the argument was officially declared over. The creator of the “GIF, Steve Wilhite, wrote into the New York Times[1] and announced that everyone who pronounced it with a hard G was “wrong”.

“It is a soft ‘G’, pronounced ‘jif’,” Wilhite declared. “End of story.”

The argument, it seemed, was over—and a lot of people accepted that, if Wilhite pronounced it like a brand of peanut butter, then we’d all have to follow suit.

But Wilhite is wrong. He has fallen into one of the oldest logical fallacies. Appeal to authority: the idea that, if someone with authority says so, the debate is over.

But authorities don’t always agree — Miriam-Webster accepts the pronunciation with a hard G[2] — and, even when they do, they aren’t always right — as anyone who’s listened to the WHO and the CDC over the last few months knows.

A G followed by an “i” is usually soft, but the G in “GIF” stands for “graphic”, so there are valid arguments on both sides.

Pronounce it however you like.

9 Slippery Slope

Is a hot dog a sandwich?

Few questions can consume the mind as thoroughly as this, and even fewer have sparked such a wide range of debate. But for all the fascinating viewpoints we’ve heard, there is one argument that needs to be shut down.

When TV performer Jimmy Kimmel[3] weighed in on this one, he fell into a classic fallacy: the slippery slope.

There’s no debate. This is a bagel. Period. What else

would you turn into a bagel? ? #BagelThat#PutPhillyOnIt pic.twitter.com/gEpO8JWs1I— PHILADELPHIA (@LoveMyPhilly) September 17, 2019

“A hot dog is not a sandwich,” he declared, arguing: “If hot dogs are sandwiches, then cereal is soup.” And if cereal is soup, Philadelphia Cream Cheese’s twitter account chimed in, then bread with a hole in the middle is a bagel.

While we can usually count on Jimmy Kimmel and Philadelphia Cream Cheese’s social media team to guide us through times of uncertainty, this time, they missed the mark. They fell into a classic fallacy: distracting us from the real debate by complaining about the consequences of the other side being right.

If a hot dog is either a sandwich or it is not. We have to decide that on its own merits (by asking: ‘what is the definition of “sandwich”?’) — and if the truth forces us to realize that all of language lacks objective meaning and that is impossible to ever truly be understood, then we just have to accept that.

But, uh, hopefully, it turns out that a hot dog isn’t a sandwich.

8 Appeal to History

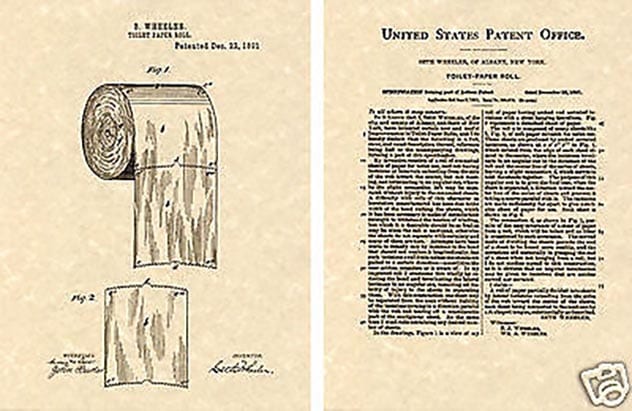

There’s no argument the internet is more confident that it has solved than the great debate over how to hang your toilet paper: over or under?

This debate raged until 2015, when somebody took the time to dig up the 1891 patent for the first perforated toilet paper roll. In the picture, the roll is hung “over” — and so the debate, the internet agreed, was over.

Multiple articles declared that over was now the “right way”[4] to hang toilet paper, or that the debate was “settled”[5] or “resolved”.[6]

But it wasn’t.

The internet had fallen into two classic fallacies at once: the appeal to authority, which we’ve already discussed, and the appeal to history: the idea that, because something’s been done one way for a long time, it must be right.

In reality, there are still valid reasons to hand your toilet paper “under”. It’s a proven way to keep cats from unrolling it,[7] and so for people with mischievous pets, it actually makes a lot of sense.

It’s swell that some guy who died a hundred years ago liked to hang his toilet paper “over”, but just because he did it first doesn’t mean you have to do it his way.

7 Ad Hominem

Sometime late last year, the young people of our world came up with the ultimate response to any debate: “OK Boomer.”

It was fun. It was a cute way of getting away with saying: “You’re old and you’re going to die, so your opinion doesn’t matter,” and enough people were doing it that, for a brief while, nobody would even get upset when we effectively told our grandmothers that we were counting down the minutes until they were scraped off the earth.

It got so big that a New Zealand Green Party politician even used it in a debate over climate change[8] — which was really one of the worst examples an ad hominem attack the world’s ever seen.

An “ad hominem attack” is an argument that essentially comes down to: “You are something I don’t like, and so everything you say must be wrong.” You’re a conservative, so you’re wrong. You’re a socialist, so you’re wrong. Racist! Wrong! Misogynist! Wrong! NAZI! Wrong! Wrong! Wrong!

And, in the case of “OK Boomer”: “You’re old, so you’re wrong.”

It might be fun to say — but when you’re a politician debating the economic feasibility of a climate change initiative, “Shut up, you’re old” isn’t really a productive talking point.

6 Argumentum ad Populum

If everybody’s doing it, it has to be right. That, in essence, is the “argumentum ad populum” — the logical fallacy that what is common (or the consensus) is correct — and it’s been put to use in some of the most vital debates in human history.

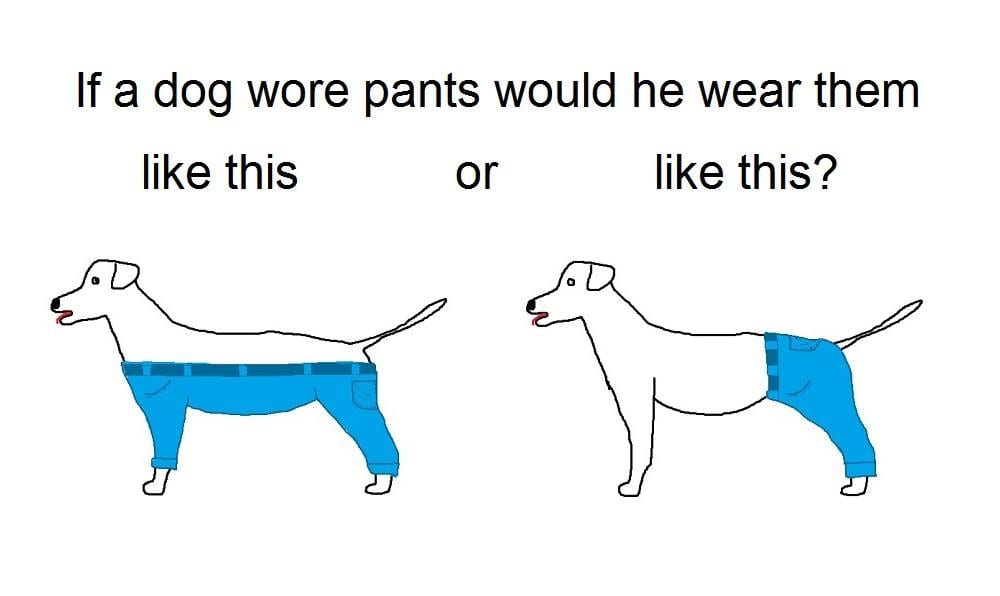

Take, for example, the question of how a dog would wear pants if it wore pants. Would it wear them over two legs or four?

There’s a near-consensus on the issue. Dogs, 81% of all people polled[9] say, ought to leave their front legs bare. After all, it’s what we’ve seen in the past.

“Every dog ever seen in pants has sported the two-legged variety,” a writer for New York magazine[10] wrote, before declaring, of the four-legged option: “It’s absurd.”

But that’s a dangerous fallacy to fall into — the idea that just because you’ve never seen something before, it must be wrong.

There is no more dangerous trap than fearing the unknown. If we reject the idea of four-legged doggy pants, we will never be able to weigh in on its merit. We will never get to see how well a dog comports itself adorned in full trousers until we try it and observe the results.

Then, of course, we’ll realize it’s absurd because they constantly fall down and are horribly restrictive on their legs. But we’ll reject it for those reasons — not just because it’s not what the majority professes.

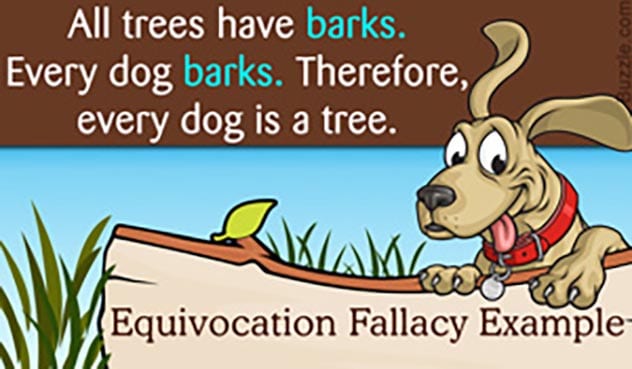

5 Equivocation

The greatest moment in internet history occurred on May 17, 2008. It was on that day that a member of a bodybuilding forum declared: “If I go every other day I will be at the gym 4-5 times a week,” and then insisted that his math was correct.

We can’t do full justice to this debate. We can only ask that you read the whole thing here.

“if I go every other day, that is 4 DAYS A WEEK. How hard is that to comprehend?” the forum member insisted. “Week 1—Sunday, Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday. Week 2—Monday, Wednesday, Friday, Sunday.”

There was an obvious problem with his math, but the man wouldn’t accept it.

“I didn’t double count sunday,” he insisted. “My two weeks started and ended on sunday, exactly 14 days.”

The problem was an issue of equivocation: calling two different things by the same name.

The members of the forum tried to explain to the misguided man how to count the number of days in a week, but he never once actually took them up on their challenge to look at the days in a week. Instead, he would look at periods of 14 days and call it effectively the same as a week, or at periods of 28 days and call it the same as a month, without ever actually looking at the number of days in a week itself.

That was the real cause of the misunderstanding. Well — that and the absolute failure of his nation’s education system. The man went on to a new career devising Common Core mathematics. Just kidding.

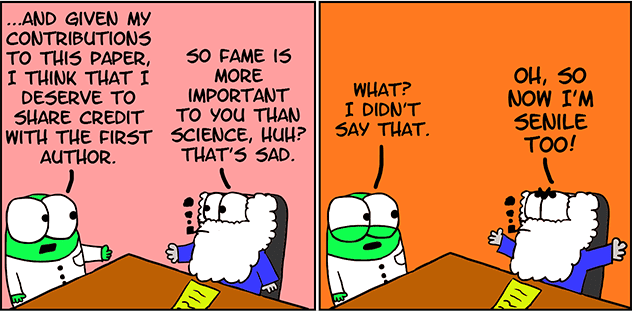

4 Strawman Fallacy

Here’s a real headline from a real, respected magazine, posted just a few days ago:

“White House: We’re Going to Have to Let Some People Die So the Stock Market Can Live”[11]

That’s not from The Onion. That’s from Vanity Fair — and it’s the type of thing we see from every side of the political spectrum today.

It’s what we call a strawman fallacy — an exaggeration of the truth that makes someone’s argument look ridiculous. And the news is full of titles like these, from every side of the spectrum:

“Man Confronts Elizabeth Warren: ‘Your Siding with ISIS, You’re Siding With Iran!’”[12]

“World Health Organization protects China instead of coronavirus victims”[13]

Depending on your political views, there’s probably at least one headline you read there that made you say: “But that’s true!” But that’s just how used we’ve become to Strawman fallacies in the news — we accept them outright.

Ideas are only ridiculous if you don’t understand them. If there’s a widely-held belief that you seem insane to you, take the time to see where they’re coming from — because odds are, it’s not that crazy.

3 Appeal to Ignorance

There’s no better example of an “appeal to ignorance” than the Mandela Effect.[14]

This is the strange theory that was born when a few people online realized that they shared a mutual lack of awareness of the fact that Nelson Mandela had gotten out of prison and become President of South Africa. Their logic, in essence, worked like this:

1. I didn’t realize something happened

2. But it’s pretty clear that it did happen

3. Therefore, reality is wrong and I am right

There was only one explanation, they decided. The universe, they declared, had branched off into an alternate timeline.

It’s an extreme version of the “appeal to ignorance”: the belief that something is true because it has not been conclusively proven false.

It’s the opposite of Occam’s Razor. Occam’s Razor would suggest that the simplest explanation (in this case, you didn’t pay enough attention in school) would be correct — but their logic says that any theory they come up with, no matter how crazy, has to be valid until you can somehow conclusively prove that it’s wrong.

It’s branched into a whole series of crazy theories about alternate realities — but, of course, the fact that you misremembered something doesn’t make you right.

Except for that thing where the “Berenstein Bears” is spelled “Berenstain” now. That thing’s crazy.

2 False Dilemma

A lot of internet arguments could be resolved if we’d just understand the “false dilemma” fallacy: the illusory idea that, in a debate, there are only two sides you can take.

Take, for example, the Yanny vs. Laurel debate. When a recording of a voice saying something that, to some people, sounded like “Yanny” and, to others, sounds like “Laurel” went viral outline, the debates got heated.

people who hear “yanny” are cultured, don’t @ me.. who the fuck is laurel

— virusmeiry (@Iilkev) May 16, 2018

People were either on team “Yanny” or team “Laurel” — and some of them were downright vicious with the other side.

People who hear “Yanny” like Nickelback. Good night.

— Nick Chester (@nickchester) May 16, 2018

“People who hear ‘yanny’ are cultured,” one woman declared, before another snapped back: “People who heard ‘Yanny’ like Nickelback.”

Honestly, in 17 years of being a parent, I’ve never thought less of my kids than I did when they said, “Yanny.”

— kelly oxford (@kellyoxford) May 16, 2018

Others were willing to turn on their own kin. One woman wrote: “Honestly, in 17 years of being a parent, I’ve never thought less of my kids than I did when they said, ‘Yanny.’”[15]

But this was a false dilemma. The right answer didn’t have to be “Yanny” or “Laurel” any more than a hot dog has to be a sandwich or toilet paper has to be hung a certain way.

Sometimes, it doesn’t have to be one or the other. Sometimes, it’s both Yanny and Laurel.

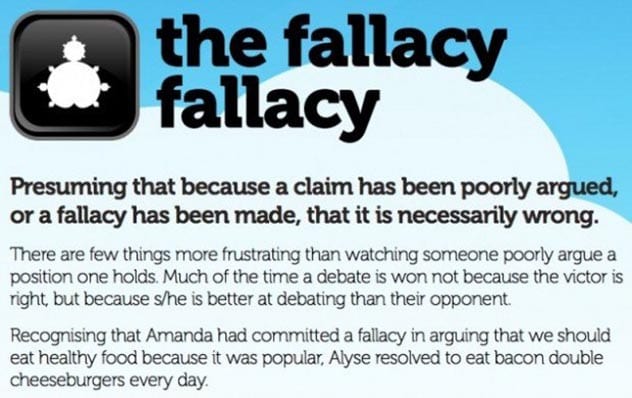

1 Fallacy Fallacy

It’s good to spot these fallacies in your own thinking and in the ideas other people push on you. But remember — just because someone uses a logical fallacy doesn’t mean that they’re wrong.

It’s called the “Fallacy Fallacy” — the belief that, because somebody uses a logical fallacy, they must be wrong.

The Flat Earth Society has a wiki page where they keep track of every fallacy anybody uses against them,[16] and they’re not necessarily wrong about that. People use appeals to authority against them, like: “NASA says the world is round, so it must be,” along with every other fallacy in this list.

But that doesn’t mean that the world is flat. The fact that we sometimes make weak arguments doesn’t flatten the world.

Sometimes, people are ridiculous — but they’re still right.

10 Wrong Words That Are Actually Right