History

History  History

History  Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

Top 10 Half-baked Sales Promotions That Ended In Disaster

Selling you stuff—it’s what mega-corporations are best at. Every year, they find new ways to get consumers interested in their products: eye-catching marketing schemes, big-budget promotional events, and, most common of all, sales promotions. Sales promotions are like advertisements, except that they also target the buyer with a promise of reward; coupons, contests, and vouchers are all examples of sales promotions. Some, like the long-running McDonald’s Monopoly campaign, drive up company profits enormously and become staples of consumer culture. On the other side of the spectrum, however, a poorly-received promotion can all but destroy a brand, as shown by these ten laughably ill-conceived examples.

Top 10 Hilarious Pranks Pulled To Promote Movies

10 Sunny Co Clothing: “Pamela” Bathing Suits

Back in summer of 2017, California-based startup Sunny Co Clothing offered Instagram users a free swimsuit, styled after the iconic one-piece worn by Pamela Anderson on the TV show “Baywatch” and valued at $64.99. All you had to do to receive it was repost the accompanying image, tag Sunny Co, and pay shipping fees—they’d handle the rest.

Unfortunately, the company massively underestimated just how many swimsuits they would have to give away. More than 330,000 people liked the original post, and despite a scourge of technical issues, the company did end up taking the L and delivering on their promise. You can’t say the error destroyed SunnyCo, as the stunt thrust them into the limelight and no doubt grew their consumer base (surely the intent of the promotion), but dishing out thousands of freebies still might not have been worth it in the long run.[1]

9 Chevy: Do-It-Yourself Ads

Rule number one of using the Internet: be prepared for anything you post to be received by a network of trolls, critics, and “memelords”—this applies double if you’re a big company like Chevy. In 2006, they partnered with the hit TV show “The Apprentice” to offer fans the chance to create their own ad for the Chevy Tahoe, through a website where anyone with a fast connection and a little bit of time on their hands could splice together clips of the SUV with custom text and their pick of pre-provided soundtrack to create—presumably—a creative piece of user-generated advertising.

Predictably, critics of the brand (especially environmentalists) saw the contest as an opportunity to create disparaging “ads” pointing out perceived flaws with the Tahoe or just Chevy in particular. Many of these submissions stayed on the contest website for indefinite periods of time, as GM (Chevy’s parent company) specifically stated they wouldn’t be removing “negative” ads, only “offensive” ones. In the end, it seems that, like many tech-illiterate corporations both before and after them, GM definitely overestimated the Internet’s innocence.[2]

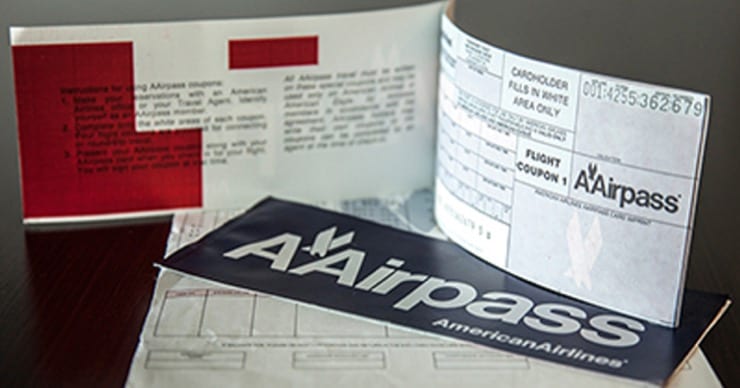

8 American Airlines: The AAirpass

American Airlines has had a bumpy history, to say the least, but their lowest point may have come in the early 1980s—a time when they were losing money fast and needed to make a quick buck to stay afloat. Their solution to the dilemma? An exclusive membership program called the AAirpass.

The idea was simple: for just $250,000, you could purchase a pass that entitled you to free first-class flights for life. Seems pretty simple, right? The trouble started when, in 2007, AA (again in the midst of financial trouble) realized some people were using their passes too much, and it was costing the company millions. While they tried to simply remove the offending passholders from the system (citing “fraudulent activity”), the matter was only settled after years of litigation. Nowadays, the program is mostly remembered as a high-profile example of a colossal business mistake.[3]

7 Red Lobster: Endless Crab

Plenty of companies have misjudged consumer demand when giving out freebies (for instance, Sunny Co Clothing), but none did it as catastrophically as Red Lobster. An “Endless Crab” promotion in 2003 cost them millions during its short-lived run and led to the resignation of company president Edna Morris, all because too many customers went back for more. Apparently, the team behind the stunt didn’t realize that, despite being quite the costly appetizer, crab just isn’t that filling.[4]

6 Build-A-Bear: Pay Your Age

Obviously, the Red Lobster mistake isn’t replicated that often. That’s because most companies are able to weigh the risks of heavily discounting items against the advantages of gaining new customers and make a balanced decision based on the data they have. However, even when the monetary side of things is accounted for, poor planning can completely ruin a potentially profitable promotion.

For instance, in 2018, Build-A-Bear announced “Pay Your Age Day”, an event during which parents could buy the company’s trademark stuffed animals for the low, low price of their child’s age. It seemed like a smart marketing tactic, until Build-A-Bear employees realized the stores were unable to handle the influx of crowds the promotion had created. Those who had to wait in line for hours—with kids in tow, no less—were less than happy, and the fiasco led to a surge in negative PR for the company.[5]

Top 10 Live Music Mess-Ups, Falls, And Fails

5 Coca-Cola: MagiCans

Coca-Cola’s “MagiCans” contest idea seemed decent, at least in theory—among the millions of regularly-labeled Coke cans distributed across the United States, there would also be a select number of disguised “MagiCans”, special “golden ticket” cans that hid prizes inside which would pop up once the can was opened. To keep the MagiCans from being discovered too easily, they were designed with a compartment inside that contained a replacement for the usual soda; a (non-toxic) mix of chlorinated water and an unknown, foul-tasting liquid clearly meant to keep the contents from being drunk.

The promotion was nixed after just a few weeks, however, after numerous reports came in of problems with the cans: the liquid ruined the prize, or the prize didn’t pop up at all, or—in one extreme case—a child drank the Coke-replacement liquid. At first, Coke did try their best to dispel concerns, but the campaign led to so much negative publicity that they finally decided to pull the plug.[6]

4 McDonald’s: When The U.S. Wins, You Win

To keep the patriotic spirit going during the 1984 Summer Games, McDonald’s created a promotional contest called “When The U.S. Wins, You Win.” The premise: buy an item, you get a game piece with the name of an Olympic event on it. If the U.S. gets a medal in that event, you get free food (a Big Mac for gold, fries for silver, and a Coke for bronze).

However, what seemed like a smart way to capitalize on the biggest sporting event of the year became a marketing nightmare for McDonald’s after the Soviet Union boycotted the games, leading to the United States performing far above expectations. So many prizes had to be given out as a result of this that some McDonald’s locations even reported a shortage of Big Macs, the chain’s signature burger.[7]

3 Malaysia Airlines: My Ultimate Bucket List

After 2014 saw Malaysia Airlines take a huge hit from two unconnected incidents that resulted in the combined loss of more than 500 passengers and crew members, the company was no doubt looking for a way to restore its image. However, a “bucket list” themed contest (which asked entrants to describe, in 500 words or less, “what and where [they’d] like to tick off on [their] bucket list”) might not have been the best option. At least the gruesome association was caught quickly, giving the airline time to rebrand the contest as a “to-do” list—albeit not before international news media had picked up the story.[8]

2 Hoover: Two Free Flights

One of the most well-known examples of a truly terrible marketing campaign was Hoover’s ill-fated “two free flights” promotion. In 1992, desperate to overcome the ongoing financial crisis, Hoover’s British division partnered with little-known airline JSI Travel to offer two free round-trip flights to anyone who bought a Hoover product worth £100 or more (about $123 USD).

Despite the fact that Hoover purposefully made it as hard as possible to redeem the flights (a controversial fact in and of itself), they just couldn’t keep up with the high levels of demand, and the ensuing scandal caused the company irreparable damage. In 1995, Hoover Europe was sold to Candy, an Italian unit that was formerly one of their primary competitors. In 2004, a BBC documentary was made about the incident, the release of which led to Hoover’s failures being brought back into the public eye; the company subsequently lost their Royal Warrant as a result.[9]

1 Pepsi: Number Fever

It’s quite possibly the only marketing snafu to date in which a simple error quite literally meant the difference between life and death: that’s right, I’m talking about Pepsi Philippines’ infamous number blunder. In 1992 (quite a year for disastrous promotions), the company introduced a contest called “Pepsi Number Fever”. Pepsi bottle caps would be marked on the inside with one three-digit number, and certain “winning numbers” would be eligible for prizes of up to one million pesos (or about $40,000 USD).

The promotion enjoyed moderate success for a couple of weeks until the night of May 25th, 1992, when the next winning number—349—was announced. Almost everybody was a winner that night—but only because Pepsi had goofed and printed winning number 349 on more than 800,000 different bottle caps, only 2 of which were “supposed” to be winners. With thousands of people trying to redeem the contest’s million-peso grand prize, Pepsi announced their mistake and offered a 500-peso consolation prize to the now-angry “prizewinners”, a move that cost them more than four times the contest’s original budget in and of itself.

The trouble didn’t end there, however, as the country continued to rally against Pepsi. Not only were thousands of lawsuits filed, but dozens of Pepsi trucks were vandalized, several Pepsi executives were issued death threats, and five people (including three Pepsi employees) were killed by grenades thrown by anti-Pepsi rioters. While things eventually went back to normal, the “349 Incident” went down in history as a projection of the worldwide economic unrest prevalent during the early 1990s, as well as a tragic example of how a tiny mistake can have big consequences for a brand.[10]

10 Deathbed Confessions And Conversions That Went Horribly Wrong

About The Author: Izak Bulten is a pop culture enthusiast and connoisseur of all things bizarre. He’s written for ScreenRant, CBR, and The Art of Puzzles.