The Arts

The Arts  The Arts

The Arts  Crime

Crime 10 Fascinating Facts about Rikers Island

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Things You Might Not Know about Dracula

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Activities That Were Once Considered Illegal

History

History Ten of History’s Hidden Secrets: Stories 99% Don’t Know About

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Who Infamously Stormed Off Set While Filming

Food

Food 10 Foods That Have Alleged Occult Powers

Sport

Sport 10 Lesser-Known Multi-Sport Alternatives to the Olympics

Humans

Humans 10 Real Life Versions of Famous Superheroes

Gaming

Gaming 10 Overused Game Villains

The Arts

The Arts 10 Masterpieces Plucked from the Artist’s Subconscious

Crime

Crime 10 Fascinating Facts about Rikers Island

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Things You Might Not Know about Dracula

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Activities That Were Once Considered Illegal

History

History Ten of History’s Hidden Secrets: Stories 99% Don’t Know About

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Who Infamously Stormed Off Set While Filming

Food

Food 10 Foods That Have Alleged Occult Powers

Sport

Sport 10 Lesser-Known Multi-Sport Alternatives to the Olympics

Humans

Humans 10 Real Life Versions of Famous Superheroes

Gaming

Gaming 10 Overused Game Villains

Top 10 Fun Facts from US Presidential Inaugurations

Ah, the American transition of executive power. It’s something the US was fairly committed to from the late 1700s until… well, approximately the 21st century. But while presidential inaugurations typically haven’t involved quite as much drama as the previous one and the one about to occur, that doesn’t mean they were all smooth sailing.

Here are ten tales constituting a walk through Inauguration Day history. I do solemnly swear that you’ll enjoy them.

Top 10 Faux Pas Committed By US Presidents

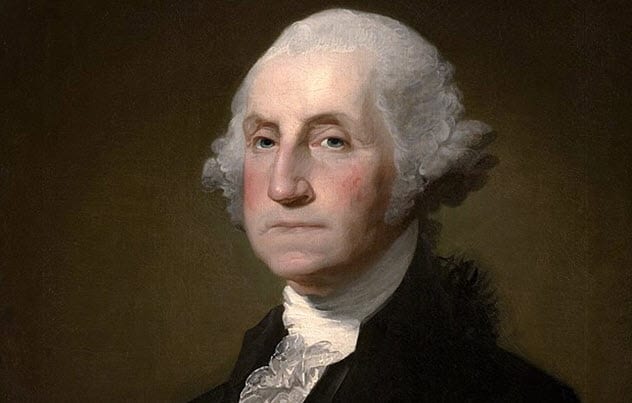

10 Say What? (George Washington)

In 1788, Congress scheduled the first-ever presidential inauguration for the first Wednesday in March of the following year. However, the brutal winter of 1789 made it impossible for many legislators to reach the then-capital, New York City. On April 6, they were finally able to assemble and announce an outcome never in doubt: George Washington was unanimously elected president.

Still, the ever-modest Washington didn’t begin the journey from his Virginia home until the results were announced, further delaying matters. On April 30, Washington was finally sworn in at New York’s Federal Hall before thousands of spectators.

Unfortunately, almost no one heard it. As portrayed in an exemplary miniseries about his vice president, John Adams, Washington tended to murmur. Regardless, in those days the ensuing inaugural address was given not to the public but to Congress.

And what an address it was. An endearingly humble man shared his hesitancy at assuming the presidency, insisting despite his many accomplishments that he was a man “inheriting inferior endowments from nature and unpracticed in the duties of civil administration,” and that he was “peculiarly conscious of his own deficiencies.”

He proceeds to thank God for the opportunity to represent what previously amounted to a ragtag group of colonies suddenly thrust into common destiny. In doing so, he pledges to self-police his authority strictly per the newly ratified Constitution, and firmly states that the collective body of Congress far outweighs his talents, authorities and importance as a lone executive.[1]

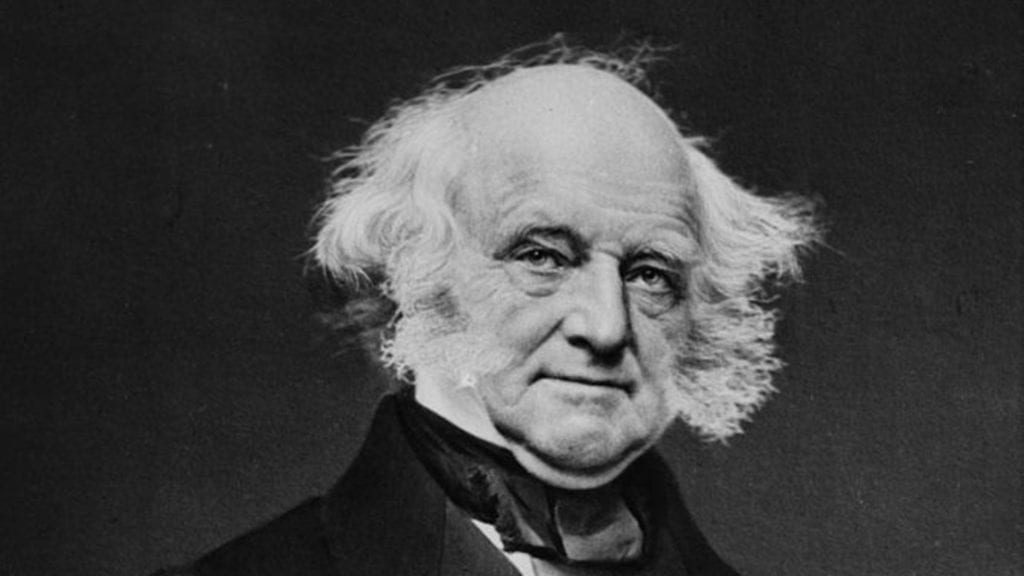

9 In With the New (Martin Van Buren)

For Martin Van Buren’s inauguration on March 4, 1837, he and outgoing President Andrew Jackson rode to the Capitol in the same carriage. It’s believed this was the first such outward display of transition-of-power unity (made easy, since Van Buren had served as vice president to Jackson, who’d campaigned vigorously for him), and began a tradition common to this day.

Exactly 40 years later, another longstanding inaugural tradition began when outgoing President Ulysses Grant invited President-elect Rutherford Hayes to the White House prior to the official Capitol ceremony. The gesture was an act of validation following a highly controversial election in which Hayes, a Republican like Grant, lost the popular vote but was awarded the presidency via Congressional commission. It’s widely believed that Hayes struck a regrettable deal – to abandon Reconstruction, the push for Black civil rights in the post-Confederate South – to win over committee members. In the process, he ushered in the terrible Jim Crow era of anti-Black laws and lynchings.

Only three presidents have declined to attend their successor’s inauguration. In 1801, John Adams left town at 4am the morning of President-elect Thomas Jefferson’s swearing in. In 1829 his son, John Quincy Adams, would one-up his famously obstinate father by departing the White House the night before Andrew Jackson took office. And in 1869, Andrew Johnson refused to attend Grant’s inauguration.[2]

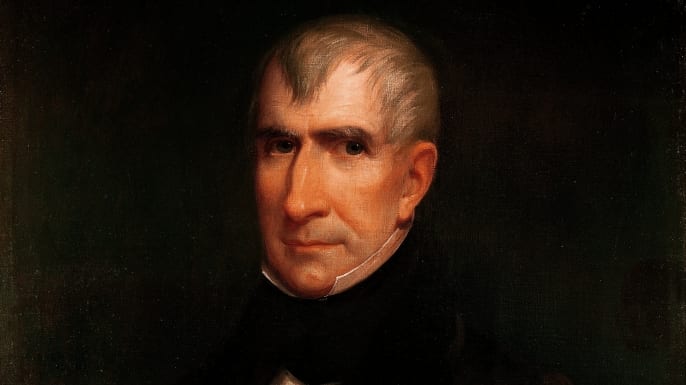

8 Hello and Goodbye (William Henry Harrison)

The shortest-serving president was William Henry Harrison, who died just 31 days after taking office. And many believe – though without conclusive evidence – that his inaugural address was to blame for his demise.

At first glance, the equation seems simple: Old + cold = fatal pneumonia. At 68, Harrison was the oldest president to that point; in fact, during the 1840 campaign, the opponents called him “Granny Harrison.” Ol’ Granny showed them alright: In a show of vitality, for his March 4 Inauguration he eschewed an overcoat, hat or gloves, then proceeded to give a 1 hour, 45-minute inaugural address that remains the longest ever.

He was dead in a month. However, historians now find it unlikely that Harrison caught his death at his welcome address. For one, he didn’t become sick until three weeks after the inauguration, whereas pneumonia typically sets in quickly. In 2014, two University of Maryland doctors posited Harrison likely died from enteric fever, pointing to contaminated drinking water – a commonality in early 19th Century Washington DC – as the culprit.

In dying, Harrison became the first president not to complete his term, and the US Constitution was unclear whether the vice president then becomes president or merely executes the duties of a vacant office. But four years is a long time for so important a position to be unoccupied, so VP John Tyler claimed a constitutional mandate, took the oath, and established a succession ritual now firmly ingrained in American tradition.[3]

7 Party Pooper (James Buchanan)

James Buchanan, America’s 15th president, nearly died just weeks before taking office. Considering his direct complicity in the Supreme Court’s shameful Dred Scott decision – which ruled that black people “were not and could never become citizens of the United States” – it’s hard not to root for the mysterious illness that befell him leading up to his March 1857 inauguration.

Weeks before his big day, Buchanan and a few close advisors took a little staycation at Washington DC’s luxurious National Hotel. All were enjoying the lavish décor, stately surroundings and sumptuous meals…

… until they got so violently ill that four of them, including Buchanan’s nephew, died.

Dubbed National Hotel Disease by contemporary media, the unknown illness left each man bedridden. Author Kerry Walters, who believes Buchanan and his cohorts may have been intentionally poisoned, wrote the “symptoms endured by all the men were similar: diarrhea, loss of appetite, cramping in the stomach, and bowels and bellies swollen by flatulence. The diarrhea was explosive and of a frothy or yeasty appearance.”

Buchanan survived – barely – but reportedly still had bouts of diarrhea up to, during and after his inauspicious inauguration. He did an equally shitty job as president: in 2017, a survey of 91 presidential historians ranked Buchanan dead last among his peers.[4]

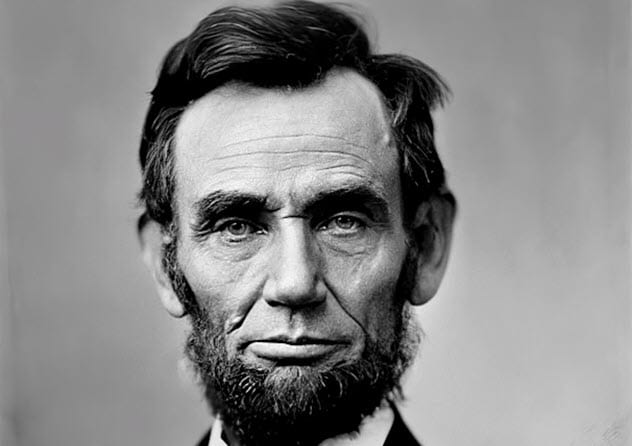

6 Assassin in Attendance (Abraham Lincoln)

On March 4, 1865, Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration became the first of its kind to be widely photographed. And one of the day’s images remains the most haunting of any ever taken at an inauguration: this photo,[5] which shows Lincoln’s soon-to-be assassin, John Wilkes Booth, perched in a balcony mere feet from the president.

In fact, a recently published book, “Every Drop of Blood: The Momentous Second Inauguration of Abraham Lincoln,” posits that Booth and his allies – all ardent Confederate supporters – had designs on killing Lincoln that day instead of a month later at a nearby theater.

“[Booth] got a pass into the Capitol building and he used that pass to slip men behind Lincoln when Lincoln was walking out to the [speech] platform, and somebody apprehended him,” author Edward Achorn said. “There’s a lot of people who thought Booth wanted to kill Lincoln right on the platform… like Brutus killing Caesar at the Senate.”

Temporarily unscathed, a president widely considered the greatest in American history delivered an inaugural speech befitting that distinction. With the Civil War winding down, reconciliation was top of Lincoln’s mind, per this immortal except: “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

Top 10 Reasons 2020 Was A Dumpster Fire

5 Bye-Bye Birdie (Ulysses Grant)

After winning reelection in 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant figured canaries would add a festive touch to his second inauguration. Unfortunately for the general-turned-Commander in Chief, Mother Nature had other ideas.

The temperature in Washington DC the morning of March 4, 1873 dipped as low as 4°F – to that point the coldest March day on record. Worse, steady gusts gave the air a wind chill “real feel” as low as -30°F. Grant’s feathered friends were indeed festive… for a while. Then they started freezing to death. Nearly 100 birds died that day, proving the timeless adage that a bird in the hand is worth several dozen in a mass grave.

More bad bird news: exactly 100 years later, at the second inauguration of Richard Nixon, the 37th president wanted to make sure pigeons didn’t ruin his big day. Never one for subtlety, Tricky Dick had a chemical repellant sprayed along the inaugural route that left the streets strewn with dead pigeons.

Notably, Grant and Nixon were both Republicans, and to this day the party remains deeply unpopular with avian voters.[6]

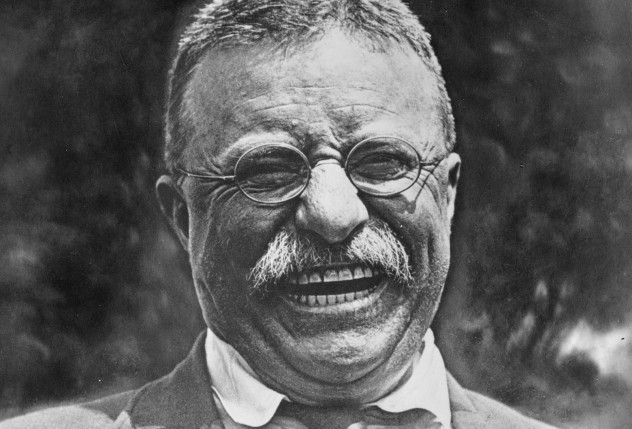

4 Ringing in a New Term (Teddy Roosevelt)

As far as his predecessors went, Teddy Roosevelt’s deepest admiration was well placed: the 26th president had a lifelong reverence for the 16th president, Abraham Lincoln. In fact, on April 25, 1865, a six-year-old Roosevelt witnessed Lincoln’s funeral procession from the second floor of his grandfather’s townhouse as it made its way through New York City.

And despite the 36-year gap between Lincoln’s death and Roosevelt taking office (also following an assassination – that of president William McKinley), T.R.’s connection with Lincoln also manifested in his cabinet. John Milton Hay, who in his 20s had served as Lincoln’s private secretary, served as McKinley’s and then Roosevelt’s Secretary of State until he passed away in July 1905.

It was just a few months before his passing, however, that Hay made an unusual contribution to inauguration lore. Forty years earlier, Hay had been so upset by the death of his boss that he paid the then-hefty sum of $100 for a few strands of Lincoln’s hair, snipped during the president’s autopsy. In a macabre fashion faux pas, Hay had the hair set into a ring Roosevelt wore the unique piece of jewelry at his inauguration on March 4, 1905 – his only one, since he originally assumed office following McKinley’s death.[7]

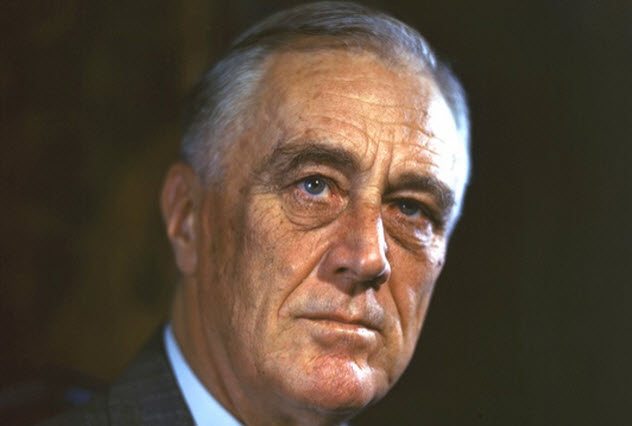

3 An Outdated Date (Franklin Delano Roosevelt)

When America was founded, news still traveled by horseback and spread through newspapers and town criers. This meant a significant lag in important news – including election results. And since a president-elect needed time to a) relocate to the nation’s capital (assuming he wasn’t a Congressman or vice president) and b) form a cabinet, a lengthy post-election period was necessary prior to Inauguration Day.

With Election Day set for early November – so placed partly due to the harvest schedule – Inauguration Day would need to be several months later. March 4 became a natural choice, as it is Confederation Day, the date in 1789 that the temporary Confederation Congress ceded authority to the permanent governing body.

By the early 20th Century, so long a lame-duck period was archaic. Telephones, automobiles and airplanes had greatly cut the reporting, travel and organization time needed for the president-elect to form a fresh, functioning administration. So in 1932 – an election year – the 20th Amendment was introduced, modernizing the inauguration date to January 20.

Unfortunately, the amendment wasn’t ratified until early 1933 – after Franklin Delano Roosevelt was overwhelmingly elected during the Great Depression. Desperate for the wide-scale government safety net and stimulus programs Roosevelt had promised – the New Deal – Americans handed him a landslide victory.

Then waited. And waited. FDR’s first inauguration was the last to occur in March, delaying action for six hungry weeks.[8]

2 An “I Do Solemnly” Do-over (Barack Obama)

It usually falls to the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court to swear in new presidents, and at Barack Obama’s first inauguration on January 20, 2009, John Roberts greeted the president-elect, instructed him to place his hand on the Bible… and promptly screwed up the oath of office. Confused at the mangling, Obama ended up saying something close to the official script, but not quite verbatim – a mix-up that also occurred to presidents Calvin Coolidge and Chester Arthur.

After what the usually-fawning media dubbed “the flub heard ‘round the world,” the two gathered the following night in the White House, with a group of reporters serving as witnesses. “Are you ready to take the oath?” Roberts asked. “Yes, I am,” Obama replied. “And we’re going to do it very slowly.”

The re-do was a no harm-no foul formality: even without it, no serious allegation of illegitimacy could have been made. The Constitution’s 20th Amendment clearly states that, following an election, the terms of the president and vice president abruptly end at noon on January 20 of the following year – and that their elected successors assume office at that time. In fact, since large events like inaugurations typically run a few minutes behind schedule, many (Obama included) take the oath after already technically becoming president.

With Roberts still serving as Chief Justice upon Obama’s reelection in 2012, the two decided to leave nothing to chance. They exchanged a copy of an oath card containing the precise wording, punctuation, and emphasis of the 35-word recitation, and the second-term ceremony went off without a hitch.[9]

1 A Handful Never Had One

Five presidents never had their own inaugurations. In all cases, they took over for a president who couldn’t complete his term; in most cases, never earning an inauguration in their own right exemplified their widespread unpopularity.

Perhaps the most forgivable failure was Gerald Ford, the most recent of this unenviable club. Not only was he succeeding a president, Richard Nixon, who’d resigned in disgrace, Ford also was never even elected as VICE president; he’d been a replacement after Nixon’s VP, Spiro Agnew, resigned amid a separate scandal. With public sentiment firmly against both his Republican party and his decision to pardon Nixon rather than continue the “long national nightmare” Watergate entailed, Ford lost to Jimmy Carter in 1976.

The most deserving of his fate was Andrew Johnson, who became president following Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, just a week after Robert E. Lee’s surrender effectively ended the Civil War. A Southern Democrat that the Republican Lincoln had made his running mate to bolster reelection prospects, Johnson opposed many of the pro-Black Reconstruction efforts passed by Congress. Fortunately the overwhelmingly Republican Congress overrode many of Johnson’s vetoes, eventually impeached him for violating a variety of laws, and fell just one vote shy of removing him from office. Johnson was so unpopular that in 1868 he wasn’t even nominated by his party, let alone reelected.

The others were the eminently forgettable John Tyler, Millard Filmore and Chester Arthur. Arthur couldn’t even win despite his close ties with a popular president, James Garfield, who’d been assassinated.[10]

10 Mind Boggling Presidential Conspiracy Theories