Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

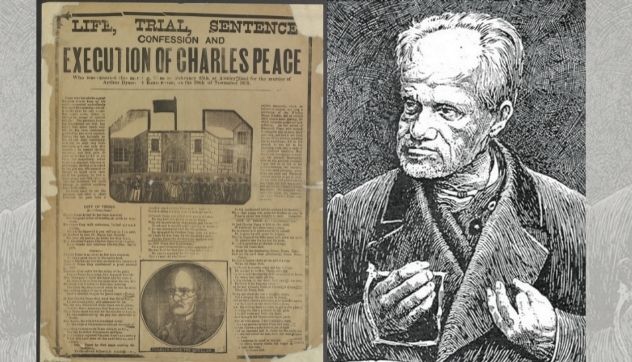

Ten Reasons Charles Peace Was a Most Interesting Victorian Rogue

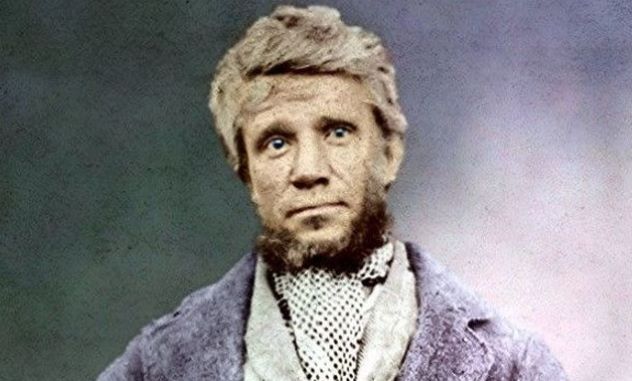

In the annals of crime, it would be difficult to come up with a more fascinating murderer than the Victorian villain, Charles Frederick Peace (1832–1879). Despite his last name, Charles Peace was a violent man—sort of a “Jekyll and Hyde.” While some saw him as a kind family man, he also had a darker side.

In looking at this life, it’s easy to see what makes him an interesting—and horrible—Victorian rogue.

Related: 10 Really Peculiar Victorian Deaths

10 Like Father, Like Son

I’m not suggesting for a moment that Charles’s father, John, a collier from Burton-on-Trent, was involved in any kind of criminality. What he and his youngest son had in common is that they each went to the Pearly Gates incomplete; John having lost his lower left leg following a workplace accident, and Charles being minus a full complement of fingers on his left hand. It says something of the family’s determination that Peace Sr. put his remaining leg at risk by becoming a wild animal tamer of some renown. In contrast, Charles became proficient on the violin, despite being digitally disadvantaged.

When he was fourteen-years-old Charles very nearly joined his father in the missing limb club while working at a Sheffield rolling mill. He suffered a horrific injury to his leg when a red-hot steel rod went through his shin just below the knee. He spent eighteen months in the hospital, and he was left permanently affected by it. However, he could walk, albeit with an unusual gait. Despite this disability, Peace became an agile cat-burglar.[1]

9 Many Strings to His Bow (But Only One to His Fiddle)

Had he not drifted into a life of crime, Peace could have probably made a comfortable living doing what he was good at. He became accomplished at everything to which he turned his hand. His skill on a single-stringed violin was such that he was in demand at soirees, and he was billed as the Modern Paganini. He dealt in antiques and art, and he was an able picture-framer and mender of clocks. He also dabbled in inventing, and he and a partner had a meeting with Samuel Plimsoll, MP at the House of Commons. This was in response to the following patent they had taken out, Peace using the name John Thompson.[2]

“2635 Henry Fersey Brion, 22 Philip Road, Peckham Rye, London, S.E., and John Thompson, 5 East Terrace, Evelina Road, Peckham Rye, London, S.E., for an invention for raising sunken vessels by the displacement of water within the vessels by air and gases.”

8 The Women in Charles’s Life

Three women would loom large in the life of Charles Peace. The first was widow Hannah Ward, who is said to have married Peace in 1851. Mrs. Ward had a young son, Willie, by her late husband. While on his travels, Peace met Susan Bailey (nee Gray) in a Nottingham lodging house. The pair began an affair, passing themselves off as Mr. and Mrs. Thompson.

However, one morning the police entered the bedroom at lodgings where the so-called Thompsons were staying. Peace refused to get dressed in front of the officers, and while they left the room to give the shy gentleman some privacy, Charles sneaked out of the building. With a price on his head, the North had become too hot for Peace and Bailey, so they headed for London, inviting Hannah Ward and Willie to join them. Here, Peace would become a one-man crime wave across Blackheath, living comfortably off the spoils.

While Peace was under arrest as John Ward, Sue Bailey betrayed him, telling police his true identity in the hope of pocketing the £100 reward. Her claim was rejected because the information she provided had not led directly to Peace’s arrest. While Peace was awaiting trial, Hannah Ward appeared at the Central Criminal Court on a charge of receiving stolen goods. The judge directed the jury to acquit on the grounds that the marriage could not be disproved; therefore, the prisoner had acted under the coercion of her husband. The third woman was Mrs. Katherine Dyson, but there’s more on her below.[3]

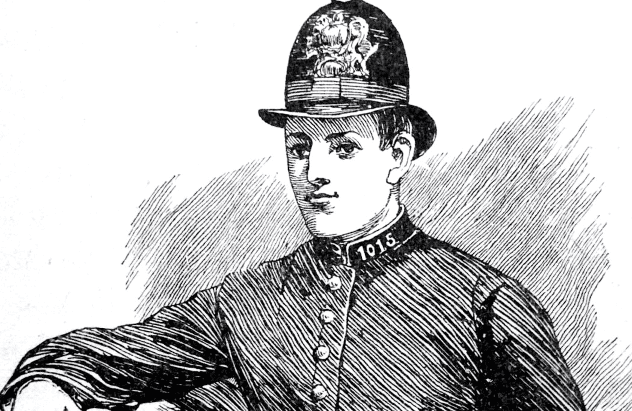

7 Peace Gets Away with Murder

In August 1876, Peace was interrupted while burgling a house in Whalley Range in Manchester. In making his escape, the desperate burglar aimed his revolver at PC Nicholas Cock, who had blocked his route. Peace fired a warning shot, and then a second that fatally wounded the unfortunate policeman. Two local men, brothers John and William Habron, were arrested and charged with the killing of Constable Cock.

Peace attended the trial of the brothers, at which John was acquitted, but William was found guilty and sentenced to death. Fortunately for the latter, he was granted a respite just two days before the date set for his execution. His sentence was later commuted to penal servitude for life. After his arrest, Peace confessed to the killing of PC Cock, and he was able to provide details that could only have been known by someone present at the shooting. William Habron was granted a free pardon and awarded £800 indemnification.[4]

6 A Second Murder

In 1877, while living in Darnall, a suburb of Sheffield, Peace befriended Arthur Dyson, a civil engineer, and his wife, Katherine. He made advances towards Mrs. Dyson, and to what extent she reciprocated is not clear, but she did admit to attending music halls and public houses with Peace. Mr. Dyson threw a card into Peace’s garden, requesting him to stop interfering with his family. Soon after this, the Dysons moved to Banner Cross, some six miles away, only to find Peace outside their new home. Peace told Dyson, “You see, I am here to annoy you, and I’ll annoy you wherever you go.”

One night, Peace was watching the Dysons’ house, and he confronted Katherine with a revolver when she came from an outhouse. Arthur came to investigate the disturbance, and Peace shot him through the temple. Later, at Peace’s trial, Katherine Dyson spent an uncomfortable time under cross-examination, particularly following the production of a bundle of letters, couched in affectionate terms and allegedly sent by her to Peace. Authorship of these letters was never established, but Mrs. Dyson made her feelings for Peace known after the trial, calling him a demon “beyond the power of even a Shakespeare to paint.”[5]

5 A Master of Disguise

As well as moving about the country in order to evade capture, Peace had the fortunate gift of being a master of disguise. His facial features have often been described as rubber-like, enabling him to change his look at will. He also used spectacles, hair dye, and walnut juice, which he applied to darken his skin to deter recognition. His missing fingers would be a giveaway, so he wore a prosthetic arm with a hook on the end to hide them. He also disguised his burgling tools, transporting them in a violin case, and he had all kinds of pockets sewn into his clothes for the concealment of tools and plunder.

Charles’s undisguised appearance was recorded somewhat unflatteringly in this description, taken from a wanted poster:[6]

“Charles Peace wanted for murder on the night of the 29th inst. He is thin and slightly built, from fifty-five to sixty years of age. Five feet four inches or five feet high; grey (nearly white) hair, beard and whiskers. He lacks use of three fingers of left hand, walks with his legs rather wide apart, speaks somewhat peculiarly as though his tongue were too large for his mouth, and is a great boaster. He is a picture-frame maker. He occasionally cleans and repairs clocks and watches and sometimes deals in oleographs, engravings and pictures. He has been in penal servitude for burglary in Manchester. He has lived in Manchester, Salford, and Liverpool and Hull.”

4 Another Policeman Shot

In the early hours of October 10, 1878, Constable Robinson was on duty in St. John’s Park, Blackheath, where a spate of burglaries had occurred. While at the rear of a house, he saw a light through the window and immediately summoned two colleagues. With Robinson remaining at the rear of the house, the other two went to the front and rang the doorbell. Robinson watched as the window opened and a man emerged. The officer gave chase, but the man turned and aimed a revolver at his pursuer. “Keep back! Or by God, I’ll shoot you,” the man said, but Robinson made a rush for him.

The burglar fired four shots, all of which missed, and Robinson was able to grab his assailant and strike him a blow to the face. “I’ll settle you this time,” the burglar said, firing a fifth shot that went through Robinson’s arm just above the elbow. Badly wounded, Robinson was still able to overpower the shooter, taking the gun from him and hitting him over the head with it. The other two officers came to assist, and Peace was arrested.[7]

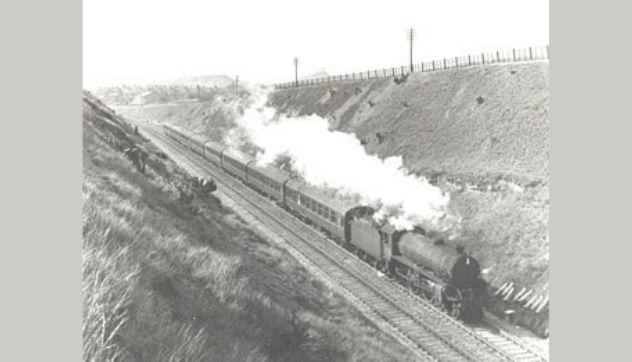

3 One last Desperate Leap

While being taken from King’s Cross to Sheffield to stand trial for the murder of Arthur Dyson, Peace was his usual troublesome self. With the train in motion, the window of the carriage was opened so Peace could throw out a bag he’d used for toilet purposes. As soon as he saw his chance, the agile rogue dived through the open window, but one of the officers managed to grab his left boot. Upside-down, Peace clung onto the footboard of the carriage while kicking wildly at the officer holding onto him.

Finally, Peace’s boot came off, and he fell to the ground by the tracks. His guards pulled the communication cord to stop the train, aghast that their prisoner had escaped. But it was not to be this time. Having run about a mile back down the track, the guards found Peace unconscious from the fall and bleeding heavily from a head wound. For Charles Peace, the game was well and truly up. After he had recovered from his injuries, Peace said that his leap from the train had been an attempt at suicide to cheat the hangman rather than an escape bid.[8]

2 Bloody Rotten Bacon

On February 4, 1879, Peace’s trial began at Leeds Assizes. After deliberating for only ten minutes, the jury returned a guilty verdict, and Peace was sentenced to death. In the condemned cell at Armley Prison, Peace confessed to a priest that he was the true killer of PC Cock. As he ate his final meal of bacon and eggs, Peace is reported to have said, “This is bloody rotten bacon.”

He presented his wife with a homemade funeral card that bore the legend: “In Memory of Charles Peace Who was executed in Armley Prison Tuesday February 25, 1879 Aged 47 For that I don (sic) but never Intended.” Charles Peace went calmly to his death; although true to form, he was even bothersome on the scaffold, asking for a drink of water. His request was refused, the lever was pulled, and this most remarkable of villains was no more.[9]

1 Charles Peace in Popular Culture

It is surprising that such a colorful real-life villain is barely represented on the big screen. In 1905, a short silent film titled The Life of Charles Peace was released. This is scant on factual information but mildly entertaining. The Case of Charles Peace (1949) is a more accurate representation, but it shows its age. Peace is mentioned by name in the Sherlock Holmes short story, The Adventure of the Illustrious Client, when the great detective comments. “My old friend Charlie Peace was a violin virtuoso.” A wax image of Peace, alongside his executioner William Marwood, was a great attraction for many years at Madame Tussaud’s chamber of horrors.

In 1964, the children’s comic Buster ran a strip titled “The Astounding Adventures of Charlie Peace,” describing him as the world’s most lovable rogue. While there is no doubt that Peace was a fascinating character, a loveable rogue may be a tad generous toward a violent murderer who wouldn’t hesitate to shoot his way past those trying to stop him.[10]