Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Quirky But Cool Uses of English

The English language is wonderfully bizarre, and sometimes rather frightful. It is a composite of the best and worst that ancient languages have to offer, and native speakers often take it for granted that they can speak it with the utmost fluency.

English does have its fair share of problems, however – not least in lexical and semantic ambiguity. This list serves to shed some light on some of the quirks and idiosyncrasies which have made English one of the most widely discussed languages in the world.

Example: The horse raced past the barn fell.

A garden path sentence refers to a type of sentence where an initial reading of the phrase will likely be incorrect; it will thus call for a re-reading. In this example, ‘raced past the barn’ is a reduced relative clause, meaning it lacks a relative pronoun – a who, which, or that. The correct parsing of the sentence would hence be ‘The horse – who was raced past the barn – fell.’ This gives a much fuller understanding of the sentence and it can now be understood that the word ‘fell’ is the main verb.

Other interpretations can also exist; a ‘fell’ could be a noun (meaning a mountain or hill). In this sense, ‘raced’ could be the verb and ‘barn fell’ could mean the fell by the barn. This leads onto the next point.

Example: I’m glad I’m a man, and so is Lola.

Syntactic ambiguity allows for multiple meanings of the same sentence. In Ray Davies’ (of The Kinks) seminal song Lola, he writes the lyric “I’m glad I’m a man, and so is Lola.” This can mean one of four things: “Lola and I are both glad I’m a man,” “I’m glad Lola and I are both men,” “I’m glad I’m a man, and Lola is also a man,” or “I’m glad I’m a man, and Lola is also glad to be a man.” Davies opted to use syntactic ambiguity on purpose and has never made it clear which interpretation is the correct one.

Other sentences might hinge on the word order of a sentence: is “The Electric Light Orchestra” an orchestra consisting of electric lights, or is it a light orchestra that happens to be electric? I suppose we’ll never know.

Example: I’ve had a perfectly wonderful evening, but this wasn’t it.

The late great Groucho Marx is credited for this comic ingenuity, a sentence which is a prime example of a paraprosdokian: a phrase which figuratively sucker-punches you. The listener or reader will have to reframe or reinterpret the earlier clause.

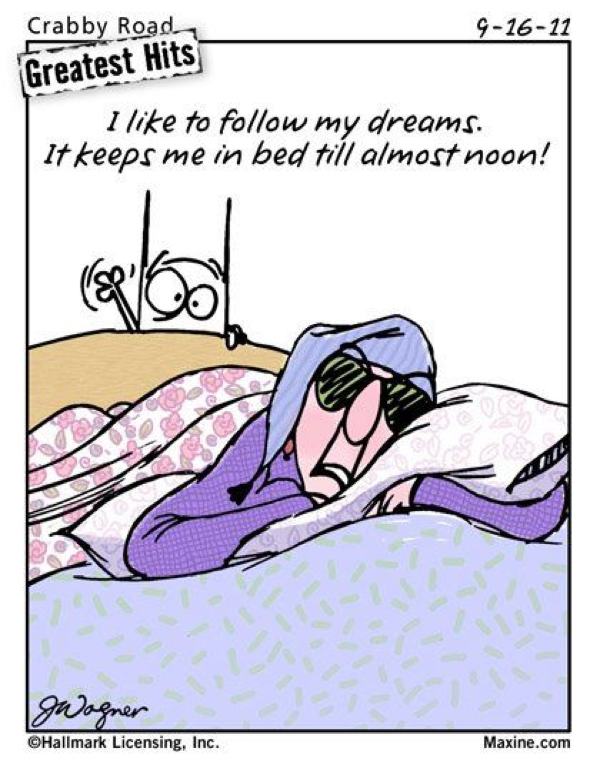

From the Greek ‘para’ meaning ‘against’ and ‘prosdokia’ meaning ‘expectation’, a paraprosdokian leaves the reader somewhat baffled by the conclusion of the sentence. They are most often used for comedic effect (and can sometimes result in an anti-climax), especially by the supremely talented Mitch Hedberg: “I haven’t slept for ten days, because that would be too long.”

A generonym is the brand name we use to mean an everyday item. These terms have seeped into the general psyche and are used more often than their technical counterparts. We almost always ‘Google’ something instead of doing an ‘online search’. Perhaps one day I will choose to ‘Bing’ it. In the US especially, many people refer to cotton swabs as ‘Q-Tips’ after their brand name. Increasingly more popular nowadays is the process of ‘Photoshopping’ an image, after Adobe’s software of the same name.

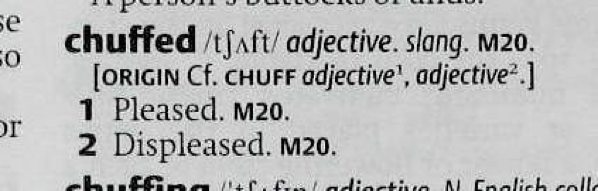

Auto-antonyms are words with multiple meanings, two of which are antonyms of one another. Some are used in everyday language without our realising it: the word ‘off’ is guilty of this. We can turn something off, meaning it will cease to be on. Conversely, the alarm can go off, meaning it has – rather bizarrely – just turned on. In more technical terms, a ‘strike’ can, in baseball terminology, mean a hit or a miss.

Synonyms are certainly the most well-known lexical phenomenon in this list; but did you know that synonym has a synonym? That word is ‘poecilonym’. A synonym (or poecilonym) is a word which has a similar understanding and meaning to another word: ‘happy’ and ‘content’ are, for all intents and purposes, synonymous with one another.

Example: Squad Helps Dog Bite Victim.

Headlinese is the nonconversational, quick language which is used for headlines (usually of print newspapers, where space is an issue). Headlinese often uses shorter synonyms and articles are usually omitted. Verbs are in the present tense, unless the future is mentioned – in this case, the full infinitive is used (“Obama to sign healthcare bill”).

Contractions and abbreviations are utilised for ease of reading as well as the aforementioned space-saving mechanism. The Republican Party is often referred to as ‘GOP’ by the US media, while honorific titles are usually discarded. ‘The Right Honorable Prime Minister David Cameron’ becomes the much easier to digest ‘Cameron’.

As noted in the example, the simple headline, which we all know and love, can often fall foul of listing number two and result in an unintended comedic climax.

Example: Our watch, sir, we have comprehended two auspicious persons.

A malapropism occurs chiefly when a word or phrase means something different from the word the writer or speaker intended to use, or if the resulting sentence is nonsensical. The phrase above comes from Act II Scene V of William Shakespeare’s comedy Much Ado About Nothing, in which the hapless Constable Dogberry informs Governor Leonato that he has captured a couple of people who are thought to have committed a crime; Dogberry mistakenly uses the words “comprehended” and “auspicious” when, of course, he meant to use “apprehended” and “suspicious.” Comic ruckus arises soon after.

The primary reason given for the use of malapropisms, especially in spoken English, is the increasing need for people to use complex language in order to communicate their desire to be seen as intellectually superior to others.

Example: Veni, Vidi, Vici.

I came, I saw, I conquered. These words uttered by serial river-crosser and one-time Roman dictator Julius Caesar, a paratactic sentence encompasses a train-of-thought mind-set where a following clause is coordinated by the previous one. In an homage to the metaphysical adherences of culture in the 21st century, the previous sentence was an example of (an unusually long) parataxis. In spoken English, rhythm, timing, and intonation set the mood for parataxis. When writing, it is important to note that psychological expression and means to express paratactic structure are important in developing a paratactic sentence.

Swift and short coordinating sub-clauses can also be used in poetry to conjoin and juxtapose two seemingly distant and fragmented ideas into a morally ambiguous sentence for the reader to infer meaning.

Example: Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.

Veritable wordsmith Noam Chomsky devised the phrase used in the example as a way to illustrate the idea that logical and grammatically correct sentences can still have no obvious meaning. Worlds collide as mathematical probability and sentence structure attempt to explain the idea of remoteness in the English language. A sentence which seems to unnaturally occur in the discourse of English will be ruled out for being too remote; a statistical model has been devised to calculate the probability of a sentence occurring. If such a sentence is outside the previously ascertained boundaries, the phrase will be unceremoniously cast away to the coffee-stained pages of linguistic textbooks as an example of logical nonsense.

The sentence itself has gained fame since its inception by Chomsky in 1955. Interpretations have been wild, but the ‘closest’ – figuratively, of course – has been “Newly formed bland ideas are inexpressible in an infuriating way.”

Example: Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo.

This unnecessary sentence is a prime example of lexical ambiguity, in which homonyms (words with the same spelling and pronunciation, but different meaning) and homophones (words that simply sound the same) can be combined to form a complex sentence structure with grammatical validity.

The proper noun Buffalo – a city in New York – is present, as is the animal buffalo. The third and most unusual term offered is that of the verb ‘to buffalo’ which means ‘to bully’ or ‘to intimidate.’ A more coherent parsing of the sentence would be “The buffalo from Buffalo who are buffaloed by buffalo from Buffalo, buffalo other buffalo from Buffalo.” The sentence offers little doubt that bison from New York are sentient and capable of emotionally scarring other bison from the surrounding area. Buffalo.

Example: It is raining outside now, but I hope that when you read this it will be sunny.

In this deictic sentence, context is required. The given example is known as temporal deixis and is contingent on the use of a timeous word which changes the meaning based on the moment in time it is said. The exact time the word ‘now’ refers to changes constantly. ‘Tomorrow’ is always the next day and that can never change, but the exact day tomorrow is always changing.

Deixis also exists when a place is discussed. “I live here” changes depending on where one lives. Likewise, “How is the weather over there?” remains an ambiguous sentence through the use of the deictic adverb ‘there’.

The final common form of deixis involves the person: “Would you go to dinner with me?” changes meaning depending on whom the ‘you’ in the sentence is. This is made even more difficult to understand in reality if more than one person is present and the speaker has no general focus.