Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Notorious Historical Murders Solved Using Early Forensics

Forensics has become an inescapable part of solving crimes. We have grown accustomed to seemingly instant answers thanks to a bevy of TV shows where a drop of blood, a small fragment of bone, or a single strand of hair often leads to the killer’s capture.

This can make us forget that forensic criminology is still a young field. All the techniques we take for granted were developed just a few decades ago when a relatively small group of pathologists and other forensic experts relied on them to solve a host of gruesome murders.

10 Crumbles Murders

The “Crumbles murders” were two distinct crimes—the 1920 murder of Irene Munro and the 1924 murder of Emily Kaye—that took place on a stretch of beach known as the Crumbles near Eastbourne.

The death of Emily Kaye was particularly gruesome. Her butchered remains were found in four large sections and dozens of small pieces in and around a bungalow at the Crumbles.

The attention of the police quickly focused on her lover, Patrick Mahon. He had motive: Kaye was pregnant with his child, but he was already married. After the interrogation, Mahon admitted to the deed, except that he presented it as an accident.

According to Mahon, he and Kaye had argued, and during an emotional fit, she had attacked him. Mahon defended himself. In the struggle, Kaye fell and hit her head on a coal bucket. Panicked, Mahon went out, purchased a knife, and returned to the bungalow to dismember the body.

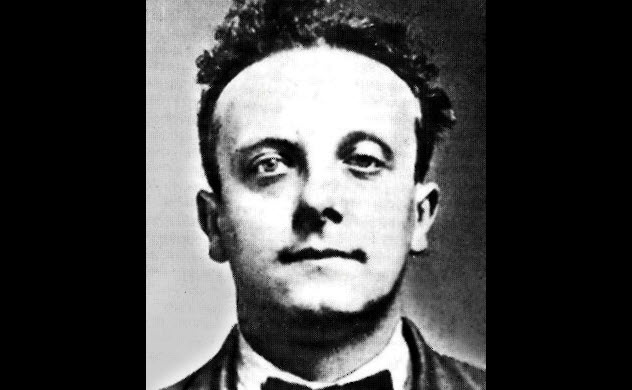

Not many people bought Mahon’s story. One person who didn’t believe him was pathologist Bernard Spilsbury, a pioneer of forensics. He set out to prove that the poorly made bucket would also have broken if Emily Kaye had hit her head on it as Mahon claimed. Spilsbury convinced the jury with a careful reconstruction of the crime scene using miniature furniture. Mahon was found guilty and hanged.

Another legacy of this case is the murder bag. At the scene, Spilsbury admonished a detective whom he saw collecting Kaye’s remains with bare hands and stressed the importance of proper gear. The following year, a kit with gloves, test tubes, fingerprinting equipment, and magnifying glasses was introduced to Scotland Yard.

9 Margate Matricide

The name “Margate matricide” was used by the media to refer to the 1929 death of Rosaline Fox at the hands of her son, Sidney Harry Fox. The two of them were staying at a hotel in Margate when Rosaline allegedly died as a result of a fire in her room. What actually happened was that Sidney had previously convinced his mother to get life insurance and then strangled her and hoped to conceal his crime with fire.

He almost got away with it. The doctor who examined Rosaline’s body was satisfied that she had died of shock and suffocation, and she was buried a week after the fire. The insurance investigators were a bit more thorough, though, as they were about to pay a substantial claim to Sidney Fox.

They noticed a patch of unburned carpet between the armchair where Rosaline was sitting and the gas stove that was the alleged source of the fire. How could the fire reach her but skip over this portion of the room?

They were suspicious enough to turn to Bernard Spilsbury, who exhumed Rosaline’s body and performed a careful post-mortem examination. Luckily, the undertaker had sealed her coffin with putty, which had prevented any serious decay.

At first glance, Rosaline showed no signs of violence or foul play. However, upon closer inspection, Spilsbury found a tiny bruise inside her throat. Then he found another bruise on her tongue and concluded that Sidney Fox had strangled his mother and used a pillow to muffle her screams.

8 The Man Who Dissolved His Wife

In 1897, Adolph Luetgert ran a successful sausage and packing company and was known as the “Sausage King of Chicago.” However, he was also in an unhappy marriage with his wife, Louisa. One night, the two of them went for a walk. She was never heard from again.

According to Luetgert, his wife went mad and simply ran away. However, police quickly suspected foul play. When they searched the Luetgert sausage factory, they learned what really happened to Louisa.

In the factory cellar, they found a vat filled with a foul-smelling, reddish liquid. After draining the vat, they found small pieces of bone, strands of hair, bits of clothes, and even Louisa’s gold ring bearing her initials.

To us, it might seem like an open-and-shut case. But this was the late 19th century, and it was difficult to prove a murder had even taken place without a body. Luetgert claimed that he was planning to mix the liquid with potash to make soap and that the bones had come from animals.

In one of the earliest examples of expert forensic testimony, the prosecution enlisted the help of anthropologist George Dorsey. He concluded that the bone fragments belonged to a human female. Along with all of the circumstantial evidence, this was enough to convict Adolph Luetgert of the murder of his wife.

7 Buck Ruxton’s Jigsaw Murders

On September 29, 1935, a young woman was enjoying a stroll through the burgh of Moffat in Scotland when she came upon a ghastly sight—a bundle stuck in a stream with an arm poking out of it. After police were notified, they combed the scene carefully and found 70 pieces of human remains.

The task of assembling this human jigsaw to identify the victims fell on John Glaister and a team of experts in pathology and forensic medicine. They determined that the victims were two women. In an early example of forensic entomology, Dr. A.G. Mearns determined the approximate time of death by studying the maggots found in the remains.

Meanwhile, law enforcement found a suspect, Dr. Buck Ruxton, through good old-fashioned police work. Parts of the bodies were wrapped in a special edition of the Sunday Graphic, which was printed for the Lancaster area 160 kilometers (100 mi) from where the bodies were found. Ruxton claimed that he had never been to Scotland. But the police knew that was a lie. Also, his wife was missing.

A breakthrough in the case came from photographic superimposition. An image of one of the skulls was superimposed over a photograph of Isabella Kerr, Ruxton’s wife, and the two were a match. The other victim was identified as Mary Jane Rogerson, Kerr’s maid. Ruxton had killed his wife in a fit of rage and then killed her maid to cover up the first murder.

6 Brighton Trunk Murders

The Brighton trunk murders were two unrelated but similar crimes that happened in Brighton in 1934. On June 17, an abandoned trunk at the city railway station was found to contain the torso of a woman.

Her identity and her killer remain a mystery to this day. But to find the rest of her, the police did a thorough search of the area. Although they did find another case with her missing limbs and head, they also discovered another trunk with another body.

This new victim was 42-year-old Violet Kaye. She was a prostitute who had fled London with her lover, Tony Mancini. Obviously, he became the primary suspect. But Mancini claimed that Kaye had been murdered by a client. Upon discovering her body, he panicked because he had a record. Mancini believed that the police would blame him, so he hid her body.

Sir Bernard Spilsbury was brought in to do the autopsy. He concluded that Violet Kaye had died from a blow to the head. A charred hammer was found in Mancini’s basement.

Meanwhile, a graphology expert testified that a telegram form allegedly written by Violet Kaye to her sister matched Tony Mancini’s handwriting. Despite the evidence pointing to him, Mancini was found not guilty.

This is largely attributed to the stellar defense of his counsel, Norman Birkett, who would go on to serve as a judge during the Nuremberg trials. Decades later, shortly before his death, Mancini confessed to the murder of Violet Kaye.

5 Wigwam Murder

During the early 1940s, Joan Pearl Wolfe was known as the “Wigwam girl” to locals around the Surrey area because she lived in improvised wigwams on a heath known as Hankley Common. However, in September 1942, she disappeared. Her body was found a month later when two Royal Marines patrolling the area saw her hand sticking out of the dirt.

Forensic pathologist Dr. Keith Simpson was brought in to examine the remains. The body was badly decomposed with almost no soft body tissue left. However, Simpson was able to assemble 38 skull fragments to reveal a large impact site at the rear of the skull, thus determining the cause of death. He established that the murder weapon had probably been a tree branch and that she had also been stabbed with a knife.

After a closer examination of the crime scene, police found a heavy branch with bloodstains. They also uncovered a love letter written by the victim to her lover, a French-Canadian soldier named August Sangret who was stationed in the area. Eventually, the police also found the knife stuck in a waste pipe.

From the letter, the police determined that Wolfe was pregnant. Sangret was illiterate, so he had relied on other soldiers to write his letters to Wolfe. They knew that he had no intention of marrying her, which likely led to a violent argument between them. Sangret was found guilty and hanged for the murder of Joan Wolfe.

4 Aberdeen Sack Murder

On April 21, 1934, Aberdeen was shocked by a gruesome discovery: The body of eight-year-old Helen Priestly was found stuffed in a sack in her building’s common bathroom. She showed signs of strangulation and sexual assault.

Police started questioning everyone in the building and soon focused their attention on the Donalds. The husband had an alibi, but the wife, Jeannie Donald, didn’t. It was known that she had contempt for the girl.

An initial examination of Helen’s body determined that she wasn’t raped. But she had been assaulted with an instrument to simulate the act and perhaps blame her murder on a man when the killer might be a woman.

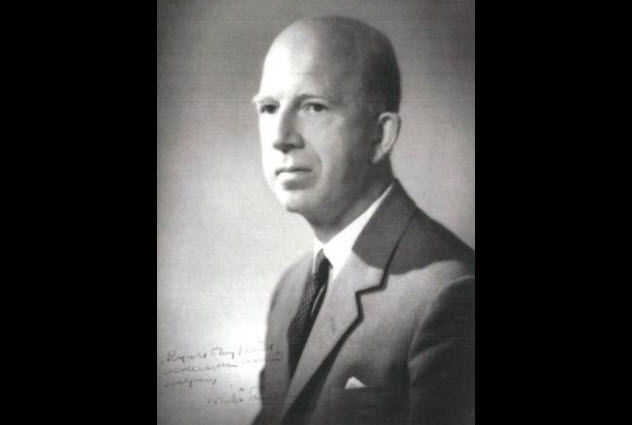

By this time, Jeannie Donald had become the police’s strongest suspect. But they needed proof, so forensic pioneer Sydney Smith was brought in to consult.

Right away, he built a strong case for the police by analyzing the dozens of fiber, hair, and trace elements found in the sack and comparing them to elements from the Donald household. He found numerous matches, making it likely that the evidence had come from their home.

Smith also analyzed bloodstains found inside the Donald house. The blood turned out to be type O, the same as Helen’s. But this didn’t prove the blood was hers until Smith had a breakthrough. He realized that the young girl’s intestines had burst during her attack, releasing bacteria into her bloodstream and making her blood forensically unique.

A bacteriologist confirmed that all of the blood samples belonged to Helen Priestly. They concluded that Helen had been killed by Jeannie Donald inside her home.

3 The Vampire Rapist

Although forensic odontology gained a prominent role in criminal investigations in the UK in the first half of the 20th century, it took a while longer for bite mark evidence to gain acceptance in North America. This was largely due to the highly publicized trial of Ted Bundy in which comparing his teeth impressions to those left on the victims helped to convict him.

But a few years before that, there was actually another case in Canada that represented the first recorded use of forensic bite evidence in North America.

In the late 1960s, several bodies of women were found in Montreal. They had been raped and strangled and had savage bite marks on their breasts. The media dubbed the killer the “vampire rapist” for the ferocity of his attacks.

By 1970, the police had connected three cases. But they only knew that the crimes had been committed by someone who went by the name “Bill.” The vampire rapist struck next in Calgary, except this time police had a suspect: Wayne Clifford Boden.

Police realized that the best way to connect Boden to the murders was through the bite marks, so they turned to orthodontist Gordon Swann. With no experience in forensic dentistry, he turned to the FBI for help. In turn, they referred him to an English expert in the field.

By comparing Boden’s teeth with the marks left on the victims, Swann showed that his teeth left the bite marks on Calgary victim Elizabeth Porteous. Boden eventually confessed to the other murders and got life in prison.

2 Bill Bayly Murders

On October 16, 1933, a small New Zealand farm town named Ruawaro was rocked by the discovery of the body of Christobel Lakey in a pond near her house. Her husband, Samuel, was missing, so suspicion quickly fell on him.

However, after an initial investigation, it soon became evident that Samuel was probably also dead and that someone was trying to make the deaths look like a murder-suicide.

The police’s attention soon turned to William Alfred Bayly, a neighbor of the Lakeys. Investigators had found bloodstains on a wheeled frame positioned near the boundary between their properties. Upon a closer inspection of the Bayly farm, authorities also found bits of burned clothes and bone fragments.

Guns missing from the Lakey house were found in a swamp on Bayly’s property. Police established that Christobel Lakey had been hit on the head and then drowned while her husband, Samuel, had been shot and burned in a drum. William Bayly was charged with their murders, found guilty, and hanged in 1934.

This case is primarily remembered for the vital role that forensics played in finding the killer at a time when forensics weren’t part of the training for the average New Zealand cop. The remains of Samuel Lakey were kept by police for investigative and forensic training exhibits and weren’t buried until late 2015.

1 Acid Bath Murderer

Almost 70 years after his death, John George Haigh remains one of Britain’s most notorious serial killers. He was dubbed the “acid bath murderer” by the media because of his penchant for dissolving his victims in sulfuric acid.

He was charged with six murders but confessed to nine, giving detailed descriptions of his actions. Despite this, Haigh still expected to walk away a free man.

He was under the impression that he couldn’t be charged with murder under British law unless police found a body. Since he was confident that there weren’t any bodies to find, Haigh indulged his arrogance and boasted of his actions to the police during an interview. However, a murder conviction was possible using only circumstantial evidence, something made far more plausible with the help of forensics.

Renowned pathologist Keith Simpson was brought in to consult. After surveying Haigh’s property, he found what appeared to be a small, polished pebble. It was actually a human gallstone. He found two more gallstones after carefully inspecting the barrels in which Haigh had dissolved his victims.

Simpson also found part of a handbag, 13 kilograms (28 lb) of human fat, dozens of bone fragments, and a partial set of dentures that was matched to Haigh’s last victim. Despite Haigh’s confidence in his “no body, no crime” strategy, he was found guilty and hanged in 1949.

Radu is into science and weird history. Share the knowledge on Twitter, or check out his website.