Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

10 More Ancient Inventions You Think Are Modern

Following on from our previous list Top 10 Ancient Inventions You Think Are Modern, we have put together this list. It includes items that were omitted from the first but are still fascinating. Most of the things found here are considered by most to have come from the modern world (or the medieval world at the earliest) but all pre-date the birth of Christ. Feel free to mention others you might know in the comments.

The Ancient Greeks and Romans are known to have played many ball games, some of which involved the use of the feet. The Roman game harpastum is believed to have been adapted from a team game known as episkyros. The Roman politician Cicero (106-43 BC) describes the case of a man who was killed whilst having a shave when a ball was kicked into a barber’s shop. These games appear to have resembled rugby football. Also, documented evidence of an activity resembling football can be found in the Chinese military manual Zhan Guo Ce compiled between the 3rd century and 1st century BC. It describes a practice known as cuju (literally “kick ball”), which originally involved kicking a leather ball through a small hole in a piece of silk cloth which was fixed on bamboo canes.

A variety of oral hygiene measures have been used since before recorded history. This has been verified by various excavations done all over the world, in which chewsticks, tree twigs, bird feathers, animal bones and porcupine quills were recovered. Many people used different forms of toothbrushes. Indian medicine (Ayurveda) has used the neem tree (a.k.a. daatun) and its products to create toothbrushes and similar products for millennia. A person chews one end of the neem twig until it somewhat resembles the bristles of a toothbrush, and then uses it to brush the teeth. In the Muslim world, the miswak, or siwak, made from a twig or root with antiseptic properties has been widely used since the Islamic Golden Age.

Sutures have a long and bizarre history, dating back to ancient Egypt, where everything from tree bark to hair was used to stitch human flesh back together again. Physicians have used suture to close wounds for at least 4,000 years. Archaeological records from ancient Egypt show that Egyptians used linen and animal sinew to close wounds. In ancient India, physicians used the pincers of beetles or ants to staple wounds shut. They then cut the insects’ bodies off, leaving their jaws (staples) in place. Other natural materials used to close wounds include flax, hair, grass, cotton, silk, pig bristles, and animal gut. The fundamental principles of wound closure have changed little over 4,000 years.

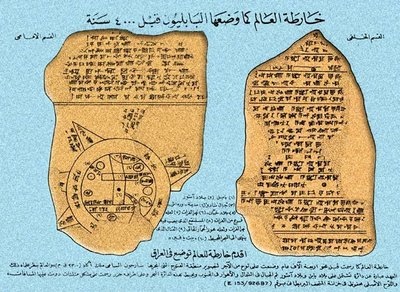

A Babylonian clay tablet that has been generally accepted as “the earliest known map” is the artifact unearthed in 1930 at the excavated ruined city of Ga-Sur at Nuzi, 200 miles north of the site of Babylon (present-day Iraq). Small enough to fit in the palm of your hand (7.6 x 6.8 cm), most authorities place the the date of this map-tablet from the dynasty of Sargon of Akkad (2,300-2,500 B.C.) The surface of the tablet is inscribed with a map of a district bounded by two ranges of hills and bisected by a water-course. This particular tablet is drawn with cuneiform characters and stylized symbols impressed, or scratched, on the clay. Inscriptions identify some features and places. [Source]

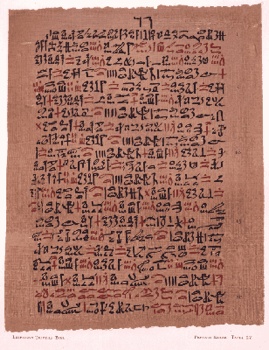

The earliest recorded evidence of the production of soap-like materials dates back to around 2800 BC in Ancient Babylon. A formula for soap consisting of water, alkali and cassia oil was written on a Babylonian clay tablet around 2200 BC. The Ebers papyrus (Egypt, 1550 BC) indicates that ancient Egyptians bathed regularly and combined animal and vegetable oils with alkaline salts to create a soap-like substance. Egyptian documents mention that a soap-like substance was used in the preparation of wool for weaving. Galen describes soap-making using lye and prescribes washing to carry away impurities from the body and clothes. The best soap was German, according to Galen; soap from Gaul was second best. This is the first record of true soap as a detergent.

The world’s earliest dockyards were built in the Harappan port city of Lothal circa 2400 BC in Gujarat, India. Lothal’s dockyards connected to an ancient course of the Sabarmati river on the trade route between Harappan cities in Sindh and the peninsula of Saurashtra when the surrounding Kutch desert was a part of the Arabian Sea. Lothal engineers accorded high priority to the creation of a dockyard and a warehouse to serve the purposes of naval trade. The dock was built on the eastern flank of the town, and is regarded by archaeologists as an engineering feat of the highest order. It was located away from the main current of the river to avoid silting, but provided access to ships in high tide as well. The name of the ancient Greek city of Naupactus means “shipyeard”. Naupactus’ repuation in this field extends to the time of legend, where it is depicted as the place where the Heraclidae built a fleet to invade the Peloponnesus.

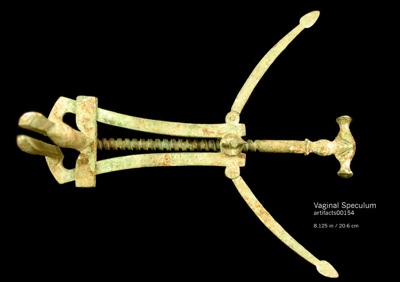

A speculum (Latin for “mirror”) is a medical tool for investigating body cavities, with a form dependent on the body cavity for which it is designed. Vaginal specula were used by the Romans, and speculum artifacts have been found in Pompeii. The original instruments were excavated from the House of the Surgeon at Pompeii, so named because of the materials that were recovered there. It comprises a priapiscus with 2 (or sometimes 3 or 4) dovetailing valves which are opened and closed by a handle with a screw mechanism, an arrangement that was still to be found in the specula of 18th-century Europe. Soranus is the first author who makes mention of the speculum specially made for the vagina. Graeco-Roman writers on gynecology and obstetrics frequently recommend its use in the diagnosis and treatment of vaginal and uterine disorders, yet it is one of the rarest surviving medical instruments. [Source]

Although vulcanization is a 19th century invention, the history of rubber cured by other means goes back to prehistoric times. The name “Olmec” means “rubber people” in the Aztec language. Ancient Mesoamericans, spanning from ancient Olmecs to Aztecs, extracted latex from Castilla elastica, a type of rubber tree in the area. The juice of a local vine, Ipomoea alba, was then mixed with this latex to create an ancient processed rubber as early as 1600 BC. Archaeological evidence indicates that rubber was already in use in Mesoamerica by the Early Formative Period – a dozen balls were found in the Olmec El Manati sacrificial bog. By the time of the Spanish Conquest, 3000 years later, rubber was being exported from the tropical zones to sites all over Mesoamerica. Iconography suggests that although there were many uses for rubber, rubber balls both for offerings and for ritual ballgames were the primary products.

In the sculptures at Nineveh the parasol appears frequently. Austen Henry Layard gives a picture of a bas-relief representing a king in his chariot, with an attendant holding a parasol over his head. It has a curtain hanging down behind, but is otherwise exactly like those in use today. It is reserved exclusively for the monarch (who was bald), and is never carried over any other person. In Egypt, the parasol is found in various shapes. In some instances it is depicted as a flaellum, a fan of palm-leaves or coloured feathers fixed on a long handle, resembling those now carried behind the Pope in processions. In China, the 2nd century commentator Fu Qian added that this collapsible umbrella of Wang Mang’s carriage had bendable joints which enabled them to be extended or retracted.

The earliest known reference to toothpaste is in a manuscript from Egypt in the 4th century A.D., which prescribes a mixture of iris flowers. Many early toothpaste formulations were based on urine. However, toothpastes or powders did not come into general use until the 19th century. The Greeks, and then the Romans, improved the recipes for toothpaste by adding abrasives such as crushed bones and oyster shells. In the 9th century, the Persian musician and fashion designer Ziryab is known to have invented a type of toothpaste, which he popularized throughout Islamic Spain. The exact ingredients of this toothpaste are currently unknown, but it was reported to have been both “functional and pleasant to taste”.

This article is licensed under the GFDL because it contains quotations from Wikipedia.