History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

Another 10 Curious Everyday Inventions

Nearly two years ago we wrote a list of everyday inventions. The list was relatively popular for its time and debunked at least one myth about the invention of peanut butter. This list is the second installment and looks at ten more items that we all come into contact with in our daily lives. These are things we tend to take for granted and we certainly wouldn’t know the name of the inventor if asked.

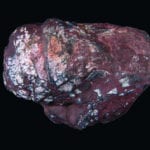

The first garden gnomes were made in Gräfenroda, a town known for its ceramics in Thuringia, Germany in the mid-1800s. Philip Griebel made terracotta animals as decorations, and produced gnomes based on local myths as a way for people to enjoy the stories of the gnomes’ willingness to help in the garden at night. The garden gnome quickly spread across Germany and into France and England, and wherever gardening was a serious hobby. Griebel’s descendants still make them and are the last of the German producers. Garden gnomes were first introduced to the United Kingdom in 1847 by Sir Charles Isham, when he brought 21 terracotta figures back from a trip to Germany and placed them as ornaments in the gardens of his home, Lamport Hall in Northamptonshire. Only one of the original batch of gnomes survives: Lampy, as he is known, is on display at Lamport Hall, and is insured for one million pounds. He is pictured above.

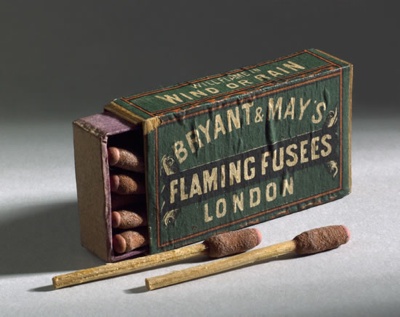

While matches existed in China in the 6th century and Europe from the 16th century, it was not until the 1800s that friction matches as we know them today were invented. The first “friction match” was invented by English chemist John Walker in 1826. Early work had been done by Robert Boyle and his assistant, Godfrey Haukweicz in the 1680s with phosphorus and sulfur, but their efforts had not produced useful results. Walker discovered a mixture of stibnite, potassium chlorate, gum, and starch could be ignited by striking against any rough surface. Walker called the matches congreves, but the process was patented by Samuel Jones and the matches were sold as lucifer matches (as they are still known in the Netherlands). In 1862, Bryant and May, the British match manufacturers began mass producing the red tipped matches we all know today, after the patent by the Lundström brothers from Sweden,

Contact lenses are surprisingly older than most of us realize. In 1888, the German physiologist Adolf Eugen Fick constructed and fitted the first successful contact lens. While working in Zürich, he described fabricating afocal scleral contact shells, which rested on the less sensitive rim of tissue around the cornea, and experimentally fitting them: initially on rabbits, then on himself, and lastly on a small group of volunteers. These lenses were made from heavy blown glass and were 18–21mm in diameter. Fick filled the empty space between cornea/callosity and glass with a dextrose solution. Fick’s lens was large, unwieldy, and could only be worn for a few hours at a time. It was not until 1949 that the first lenses were produced that sat on the cornea only and allowed for many hours of wear.

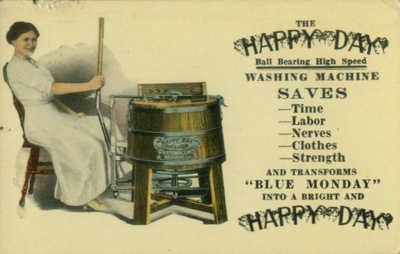

The first patent for a non-electrical washing machine was issued in England in 1692. Nearly two hundred years later, Louis Goldenberg of New Brunswick, New Jersey invented the electric washing machine (late 1800s to early 1900s). He worked for the Ford Motor Company at that time, and all inventions that were created while working for Ford under contract, belonged to Ford. The patent would have been listed under Ford and or Louis Goldenberg. Alva J. Fisher has been incorrectly credited with the invention of the electric washer. The US patent office shows at least one patent issued before Mr. Fisher’s US patent number 966677.

The early metal beverage can was made out of steel and had no pull-tab. Instead, it was opened by a can piercer, a device resembling a bottle opener, but with a sharp point. The can was opened by punching two triangular holes in the lid — a large one for drinking, and a small one to admit air. This type of opener is sometimes referred to as a churchkey. As early as 1936, inventors were applying for patents on self-opening can designs, but the technology of the time made these inventions impractical. Later advancements saw the ends of the can made out of aluminum instead of steel. In 1962, Ermal Cleon Fraze of Dayton, Ohio, invented the integral rivet and pull-tab (also known as rimple or ring pull), which had a ring attached at the rivet for pulling, and which would come off completely to be discarded. These were eventually replaced almost exclusively by the stay tabs we still use today. Stay tabs (also called colon tabs) were invented by Daniel F. Cudzik of Reynolds Metals in Richmond, Virginia, in 1975.

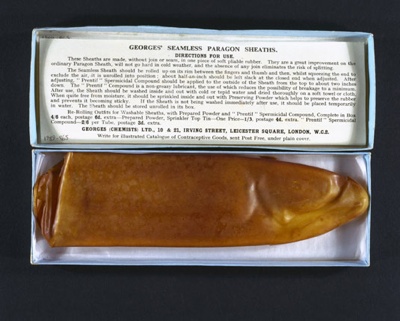

The first rubber condom was produced in 1855. For many decades, rubber condoms were manufactured by wrapping strips of raw rubber around penis-shaped molds, then dipping the wrapped molds in a chemical solution to cure the rubber. In 1912, a German named Julius Fromm developed a new, improved manufacturing technique for condoms: dipping glass molds into a raw rubber solution. Called cement dipping, this method required adding gasoline or benzene to the rubber to make it liquid. These condoms were re-usable. Latex, rubber suspended in water, was invented in 1920. Latex condoms required less labor to produce than cement-dipped rubber condoms, which had to be smoothed by rubbing and trimming. The use of water to suspend the rubber instead of gasoline and benzene eliminated the fire hazard previously associated with all condom factories. Latex condoms also performed better for the consumer: they were stronger and thinner than rubber condoms, and had a shelf life of five years (compared to three months for rubber).

Foil made from a thin leaf of tin was commercially available before its aluminum counterpart. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, tin foil was in common use, and some people continue to refer to the new product by the name of the old one. Tin foil is stiffer than aluminum foil. It tends to give a slight tin taste to food wrapped in it, which is a major reason it has largely been replaced by aluminum and other materials for wrapping food.

The first audio recordings on phonograph cylinders were made on tin foil. Tin was first replaced by aluminum starting in 1910, when the first aluminum foil rolling plant, “Dr. Lauber, Neher & Cie., Emmishofen.” was opened in Kreuzlingen, Switzerland.

The first patent on a ballpoint pen was issued on 30 October 1888, to John J. Loud, a leather tanner, who was attempting to make a writing implement that would be able to write on the leather he tanned, which the then-common fountain pen couldn’t do. The pen had a rotating small steel ball, held in place by a socket. Then, fifty years later, with the help of his brother George, László Bíró, a chemist, began to work on designing new types of pens. Bíró fitted this pen with a tiny ball in its tip that was free to turn in a socket. As the pen moved along the paper, the ball rotated, picking up ink from the ink cartridge and leaving it on the paper. Bíró filed a British patent on 15 June 1938. Earlier pens leaked or clogged due to improper viscosity of the ink, and depended on gravity to deliver the ink to the ball. Depending on gravity caused difficulties with the flow and required that the pen be held nearly vertically. The Biro pen both pressurized the ink column and used capillary action for ink delivery, solving the flow problems.

Shampoo originally meant head massage in several North Indian languages. Both the word and the concept were introduced to Britain from colonial India. The term and service was introduced in Britain by a Bengali entrepreneur Sake Dean Mahomed in 1814, when Dean, together with his Irish wife, opened a shampooing bath known as ‘Mahomed’s Indian Vapour Baths’ in Brighton, England. During the early stages of shampoo, English hair stylists boiled shaved soap in water and added herbs to give the hair shine and fragrance. Kasey Hebert was the first known maker of shampoo, and the origin is currently attributed to him. Originally, soap and shampoo were very similar products; both containing surfactants, a type of detergent. Modern shampoo as it is known today was first introduced in the 1930s with Drene, the first synthetic (non-soap) shampoo.

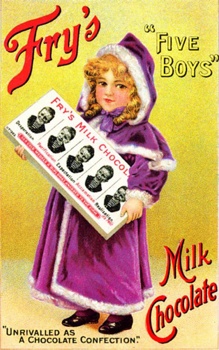

Up to and including the 19th century, candy of all sorts was typically sold by weight, loose, in small pieces that would be bagged as bought. The introduction of chocolate as something that could be eaten as is, rather than used to make beverages or desserts, resulted in the earliest bar forms, or tablets. In 1847, the Fry’s chocolate factory, located in Union Street, Bristol, England, moulded the first ever chocolate bar suitable for widespread consumption. The firm began producing the Fry’s Chocolate Cream bar (arguably the best tasting chocolate bar in the world in my opinion) in 1866. Over 220 products were introduced in the following decades, including production of the first chocolate Easter egg in UK in 1873 and the Fry’s Turkish Delight (or Fry’s Turkish bar) in 1914. By 1919 the company merged with Cadbury’s chocolate and the joint company named British Cocoa and Chocolate Company.

This article is licensed under the GFDL because it contains quotations from Wikipedia.