Humans

Humans  Humans

Humans  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

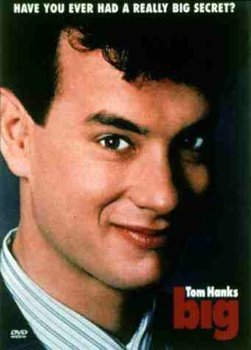

Top 10 Male Lead Performances in Film

A couple of these men did not win the Oscar for the listed performance. But they should have. I do not fault the Academy for its mistake in these instances, because the years in question saw savage competition in the lead actor category, and any result was going to be controversial.

It’s still this lister’s pick for Hanks’s best performance. Not to take anything away from his two Oscar winners, but he should have won for this one (and not for Forrest Gump: John Turturro, in Quiz Show, should have won that year).

It’s pristine, effortless acting, in the same vein of Spencer Tracy and Laurence Olivier, as opposed to “the Method.” Hanks explained that he just pretended to be a kid again, and had a lot of fun with it.

He plays the innocence card into the rafters in this film, and you can never tell it’s Hanks. It’s always the character, Joshua Baskin.

The Oscar, in 1988, went to Dustin Hoffman, in Rain Man, and it’s fine work, but non-fictional representations always come across as somewhat cheap, since they’re impersonations on some level. Whereas, a fictional character is all up to the actor.

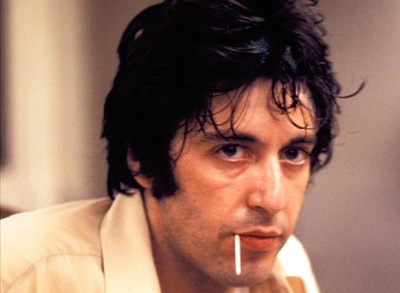

A bravura standout among bravura performances, and yet, bravura seems to imply going over the top. Pacino never does in this one. The real amazing part is that this is a true story!

He plays a loser who robs a bank, desperate for the money to pay for his gay lover’s sex change operation. Not even Shakespeare could have come up with that. The whole premise, thus, is alternately hilarious and hideous, insane and idiotic, and Pacino hits all the right notes for these aspects. His goal is to come across as more of a hero than a villain, and he actually succeeds, despite his grotesque motive!

The Oscar, in 1975, went to Jack Nicholson, in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and it’s definitely superb, but Nicholson plays an ordinary rabble rouser who treats his crazy asylummates to a few fun days, but it should be a heroic performance, and Nicholson focuses a little too much on breaking Nurse Ratched’s rules solely for the sake of breaking them, not for the sake of his friends.

It’s his finest performance to date, and here’s hoping for lots more. A tour de force of consummate reserve, effortless artistry. He plays a dirty old man, infatuated with a teenage girl named Venus.

But he has to face facts. He has regular colonoscopies to check for cancer. He’s old! He’s wrinkled and rickety! But he defies the facts. He wants Venus. No one alive could have done this role. O’Toole draws all eyes with him everywhere he walks, even in small rooms. The rest of the cast seems to come alive with a little of his energy. He pulls a Spencer Tracy, with mastery in an aura around him.

The Oscar this year went to Forest Whitaker, in The Last King of Scotland, and it’s a hell of a performance, but O’Toole’s role was much more complicated and difficult to do well. He’s been plagued with bad luck throughout his career. Gregory Peck was better as Atticus Finch. But O’Toole should have won for The Lion in Winter, hands down. And for this.

It remains the finest comic performance in film history, for more than one reason. Sellers undertook the monumental task of playing 4 (FOUR!) roles at once, all distinct and all comic, and couldn’t manage the role of Major T. J. “King” Kong, whom Slim Pickens finally portrayed.

Sellers finally managed the Texian accent, but just couldn’t stay in character. He may have broken his ankle on purpose to escape his contract and play only 3 roles. But we can certainly forgive him, in view of the brilliance he displays in 3 guileless, chameleon-like performances. Judos to the makeup crew, of course, but the truth mainly lies in Sellers, whom you cannot recognize as Sellers in any of the roles.

To put his genius into perspective, consider that Stanley Kubrick was notorious for an explosive temper on set, which he excused with the explanation, “Actors don’t know their lines.” He wanted the script followed to the letter and only twice in his career allowed ad libbing: Sellers in this film, and GnySgt. R. Lee Ermey as, more or less, himself, in Full Metal Jacket.

Remember the phone call scene when President Muffley calls the drunken Russian Premier Kisov? That entire one-sided conversation came off the top of Seller’s head. Kubrick had nothing written in the screenplay except “Phone: Muffley to Kisov. Peter ad libs.”

He did the whole thing in 3 takes, the first interruption because of laughter from Kubrick himself, the second on purpose by Sellers, who started having fun with Kubrick’s personal life, and the third because the whole set was cracking up. He improvised the “alien hand syndrome,” which has since been nicknamed the “Strangelove Syndrome” in his honor. He based Group Captain Lionel Mandrake on Alec Guinness, because he thought it would be hilarious to see Alec Guinness with a clueless sense of humor.

One of the few flawless performances in film. You never think “Paul Scofield.” You think “Thomas More.” This play had been on stage before, but the movie public had little idea of what Thomas More, the man who wrote the wonderfully witty indictment of Henry VIII and absolute power, “Utopia,” was like personally.

The film is accurate regarding his character. More really was unyielding on religious grounds: he was a staunch Catholic, and knew more about God and Jesus than anyone in England. He was adamant that Protestantism was Satanic and faithless, but he was extraordinarily forgiving toward Luther and all sinners. At the same time, he was the shrewdest lawyer and politician in the world, and Scofield nails all of this. His portrayal of More is the finest Christ-like characterization to date, better than Max von Sydow, or Jeffrey Hunter, or Jim Caviezel. Shame there hasn’t been a really, really good portrayal of Jesus.

Marlon Brando would stand in awe, in awe, of the diligence Day-Lewis put into this role. He spent a year before production began, practicing his John Huston voice and getting into character as a ruthless oilman who only cares about one thing: beating everyone else, at life.

When the cameras started rolling, he found it easy to say anything he wanted and have it come out just right, because he claimed he was unable at times to come out of character. His second speech to townspeople, advertising his drilling services was completely ad libbed. Director Paul Anderson considers it the finest scene in the film.

“It’s spot-on characterization. Pure Plainview.”

The movie itself is complicated and fascinating, but the ending leaves a bad aftertaste. Yet Day-Lewis dominates everything. In an extremely rare occurrence of lightheartedness, Day-Lewis replied to the question, at the after-Oscars press conference, “What’s your favorite milkshake flavor?” with a wry smile and said, in Plainview’s voice, “Whichever flavor your drinking. I drink your MILKSHAKE!”

In only 16 minutes, Hopkins redefined the nature of villainy. It has to scare you as well as anger and disgust you. This is not a Method performance. Hopkins took Katharine Hepburn’s advice, from the set of The Lion in Winter, and did not try to act. He just said the lines. He based Lecter’s voice partly on Hepburn’s.

He came up with the idea of standing up and waiting for Clarice to appear at their first meeting. The script, like the book, called for him to be lying in bed, not particularly intent on her. Hopkins argued that if this was the first woman he had seen in 8 years, he was going to stand up and pay attention. And he thought it would be scarier to stand there, simply and with that soulless grin that oozes politeness and pure malice.

Add to that his unnerving stare whenever he talks to someone. He claims that he never blinked while speaking, though he seems to do so about twice. Never mind that, he hypnotizes you into terror and horror at the same time.

Remember the slurping sound after his most famous line? “A census taker once tried to test me. I ate his liver with some fava beans and a nice Chianti. *slurpslurpslurpslurpslurp*” That slurping sound was his idea, on the spur of the moment. Jodie Foster claimed that she almost defecated right then. He also enjoyed mocking Clarice’s accent, which he claimed was really mocking Foster’s fake West Virginian accent. She said later that he scared and infuriated her when he did it.

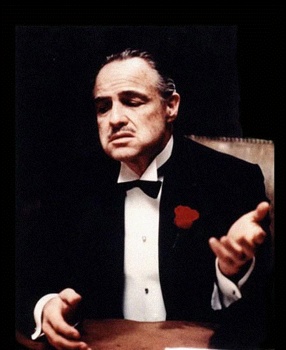

The greatest Method performance in history. You have to be bad-ass to out-act Al Pacino, James Caan, and Robert Duvall at the same time. They were all nominated in the supporting category, and yet, astoundingly, Brando pulls it off. He towers over everyone.

Director Coppola explained what it was like to witness genius so intimate with its craft creating a character. “I went to his house with the script. He looked it over for about an hour while we waited. Total silence. Then he reached over to a box of Kleenex on his nightstand, wadded some up in his mouth, in his cheeks, and started saying the lines, and it came out as Vito Corleone. Right then, the way I always heard him in my head. Then he started improvising monologues in various scenes. It was out of this world.”

He shines at his absolute pinnacle as the murderous mafioso conflicted with his sinful life, when Duvall tells him that his son, James Caan, has just been killed. For a moment, he says nothing. But you can watch his heart break. It’s all in his face. He looks up, as if praying for mercy. Then he does NOT call for retaliation. He calls for a truce. Nobody could have done it better than Brando.

It’s the most magnificent, living, breathing, soulful bravura performance in film. Salieri, Mozart’s rival, is quite a daunting role, due primarily to the amount of emotion and pathos in his character. It’s fictitious in large part, as the real Salieri might have hated being nothing compared to Mozart, but he would never have deprived his own ears of such genius. He loved Mozart’s music.

But in the film, Salieri poisons Mozart out of desperation to become loved throughout the world as a great composer. He intends to put his own name on Mozart’s Requiem (like any musicologist would have believed it).

But he can’t live with himself after doing it, and tries to kill himself. Then he confesses to a priest. Everything he says as an old man will haunt you. He’s miserable. He’s still eaten up with hatred, especially when reminiscing. He’s one hell of a villain because of all this complexity of emotion.

Abraham gets it all right. The pauses between words, phrases, the expressions, the body language. Nothing is out of place. As the young Salieri, he immerses you into himself. You see everything as Salieri sees it.

It may be the only perfect performance in motion pictures. Katharine Hepburn, Tracy’s love for years, actually said this to Anthony Hopkins, on the set of The Lion in Winter: “Don’t act. Don’t try to do anything. Just say the lines. And watch Spencer Tracy movies.”

Well, no one has ever done it better than Tracy as Father Flanagan. The interesting thing is that he did not impersonate the real Flanagan. A Method actor would. Or as Charles Laughton said, “A Method actor gives you a photograph. A real actor gives you an oil painting.”

Tracy considered that an actor’s job, not studying the real guy and then copying him. So the characterization is part real and part Tracy, but all true. He’s also one heck of a hero for always believing in the goodness of some of those rotten little kids.

Never once, during the film, are you aware that you’re watching an actor. You think you’re watching true life. It’s not a performance as much as an entity. Flanagan comes alive and altogether unique in Tracy.

His own maxim on acting is Hemingwayesque: “Son, acting is the easiest thing in the world to do. Just don’t get caught doing it.”