Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

10 Greatest Works of Christian Fiction

Christianity was the founding religion of both the Western and Eastern empires and, as is to be expected, enormous amounts of literature has been produced based on the tenets and ideals of Christianity. This list looks at ten of the greatest masterpieces in writing which come from a Christian perspective.

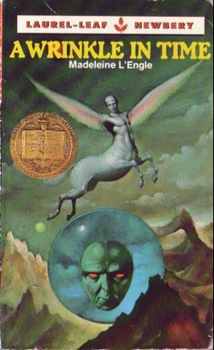

This book makes the list primarily for mixing science and Christianity in a favorable way. The two subjects are often seen as being at odds with each other, but in L’Engle’s book, the protagonist, Meg Murry, and her scientist family, all very intelligent, discover a way to fold space-time and travel anywhere in the Universe, instantly. They go to the planet Uriel, which is like Heaven, where everything is good and winged centaurs sing praises. They then learn that the Universe is being attacked by a monster called the Black Thing. The Black Thing captured Meg’s father when he was working on faster-than-light travel, and took him to the planet Camazotz, where everything is controlled by a disembodied brain called IT. IT demands absolute conformity, to the point that all houses and towns and cities look precisely the same. Camazotz has been enveloped by the Black Thing, of which IT is the ruler.

Throughout the book, Meg and family discover many fascinating things, including three immortal women named Mrs. Which, Mrs. Whatsit, and Mrs. Who, each of whom is very unique. Mrs. Who speaks several languages, and frequently quotes Shakespeare and the Bible. The protagonists finally wind up at Camazotz, and her brother is kidnapped by IT. The rest of them escape, but after learning how to defeat IT, Meg goes back to rescue her brother. IT cannot tolerate the emotion known as “love.” They return to Earth much the wiser about how to live decently and treat others well.

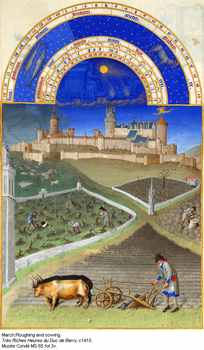

One of the more explicit allegories, with every character named for the quality or emotion he or she displays. In Malvern Hills, Worchestershire, a man named Will (free will) dreams of a tower on a hill, and a fortress in a valley (Heaven and Hell), and a “fair field full of folk,” between them (mankind). He sets out on a journey to attain the tower. Piers, a plowman, appears and offers to guide Will to the tower. On the way, Piers speaks to him of Truth, while Will searches for anyone who might enter the tower with him, namely Dowel (Do well), Dobet (Do Better) and Dobest (Do Best). Will is searching for how a Christian should live, according to Catholicism.

It is ranked so low on this list because, although it deals with Christianity in post-Black Death England, it is more a critique of English society at that time. It’s reliance on Christian philosophy and morality, however, requires that it be given a spot here. Various characters meet up on a road as they walk to Canterbury Cathedral to see the shrine of Thomas Becket. There is a knight, a miller, a cook, a friar, nuns, etc. They decide to have a story contest to pass the time, and the stories they tell all deal with various principles and ideas of the Catholic Church in England at that time.

Chaucer wrote this work during the Great Schism, as it is known now. The Catholic Church split right down the middle in 1378, and this lasted until 1417, after his death. One pope said the throne should be in Rome. Another claimed himself as pope and said it should be in Avignon, France. It was finally resolved with a Council and a few excommunications, and the election of a new pope in Rome. The tales show a diversity of theological understanding, various disagreements, and yet, the characters remain together in their journey to Canterbury, which Chaucer uses to symbolize Christianity holding all its followers together, whether they agree or not on any issue.

“Psychomachia” means “Battle for the Soul.” It ranks so high, despite not being well known, for being one of the very first, if not the first, Christian allegories. It is an epic poem of about 1,000 lines, not very long, which tells the story, in the style of Virgil’s Aeneid, of a titanic and desperate battle between virtues and sins, inside a nameless character, intended as the reader. All the famous deadly sins and cardinal virtues are present, though not precisely listed in their modern forms. Pagan idolatry initiates the conflict, bringing Pride into the fray, which is defeated by Selflessness, and so on. The final fight is comprised of the double threat of Hatred and Wrath versus Love, which finally defeats all sin in the name of Christ Jesus. 1,000 Christian martyrs then praise the Faith with a Hallelujah.

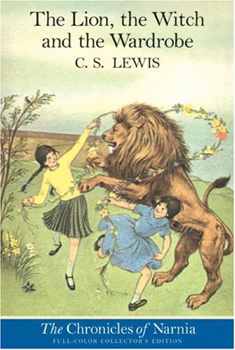

His entire Narnia series of children’s books teem with Christian themes, but the first that he wrote, and most famous, is the most explicit, being a loose retelling of the life of Jesus. “Aslan” is Turkish for “Lion.” And for the child in all of us, Lewis includes talking animals, lots of magic, fantastic creatures like centaurs and unicorns, naiads and dryads, which are like tree spirits (similar to Tolkien’s ents). Narnia is under the spell of Jadis, the White Witch, who has set herself up as the Queen of Narnia, and makes it eternally frozen and snowing, but never Christmas.

Four children from Earth find their way into Narnia, and discover that their arrival is predestined, and heralds the long-awaited coming of Aslan, who will right all the wrongs. Along the way he teaches them what is virtuous, what is sinful, and then deals with the error made by one of them, Edmund. The Witch demands the boy die for the crime of betraying his own siblings. Aslan offers himself in the boy’s place, and the Witch thinks that this Deep Magic will give her control over Narnia once and for all. Boy, is she wrong.

Many critics believe that Christmas is the most popular holiday around the world at present, not because of the Nativity story, but because of its revival in Dickens’s mid-Victorian novella about charity for all, regardless of religion, social standing, or anything else. In secular terms, that is what Christmas should be about, he argues in this book: giving to others without thought of recompense; the one time of the year when all differences should be put aside for a brotherhood of man.

Ebenezer Scrooge is an odious miser, a money lender, who refuses to give money to anyone for nothing. He lends to those he thinks can pay him back, but he charges quite a lot of interest, and is quick to charge more when payment is late. He does not care how poor or unable anyone is to pay him back, or how desperately they need food and shelter. But that all changes on Christmas Eve, when he is visited by the ghost of his old partner, Marley, who warns him that he is in danger of Hell. Then the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet to Come, visit him and show him how horrible a man he is. He changes for the better and everyone lives happily ever after, beginning on Christmas Day.

Many of the story’s elements have entered the vernacular around the world. Misers are now nicknamed Scrooges, and people much more frequently say, “God bless us, everyone.”

But is it explicitly Christian? Yes, it must be considered so, because even in secular terms, the root of the word Christmas cannot be ignored, and Dickens chose this holiday over all the others. Thus, the principles of charity for all and generosity and love are evoked in Christ’s name.

The most obviously allegorical of all Christian allegories. The protagonist is named Christian, who reads the Bible and then is burdened by a heavy packpack, which holds the knowledge of his sin. He is met in the fields one day by a man named Evangelist, who directs him to the Wicket Gate. Christian immediately leaves his wife, children, and home to seek the Gate and a deliverance from his sin, lest he sink in Tophet (Hell). Tophet is thought to be where, in Jerusalem, the Canaanites sacrificed children to the god Moloch by roasting them to death. Christian is diverted on his journey by Mr. World Wiseman, who tempts him to seek deliverance through the law (earthly law). Christian refuses and reaches the gate, where Good Will instructs him further. He finds the place of deliverance, which is Calvary, where the straps of his backpack snap and he is relieved of his burden. In the 2nd part, Christian’s family finally goes after him and thus finds deliverance from their sins, and reunion with Christian in Paradise. Good Will reveals himself as Jesus.

It is probably the longest single epic poem in English, and Spenser intended it to be twice or four times as long as what he finished. It is 6 Books, each celebrating a particular virtue: holiness, temperance, chastity, friendship, justice, and courtesy. The first book is the most famous, since Spenser wrote in such a laid-back style that it takes him quite a long time to say anything, and most readers quit with the first book. He also invented the Spenserian stanza for the work. In the first book, the protagonist is the Redcrosse Knight, symbolizing King George of England (the red cross was and still is on the English flag).

He rides over the English countryside, getting into adventures, and rescuing Una, a damsel in distress, who symbolizes both Queen Elizabeth I and the Virgin Mary. She travels with a lion (God’s law) and a lamb (God’s love). She recruits him to save her family’s castle from a monstrous dragon (Satan), whom the Redcrosse knight defeats in combat after putting on the armor of God. This duel, near the end of the first book, is one of the most famous events of the poem, and a classic tale of a knight slaying a dragon. The protagonists come across various villains on their journey, such as Duessa, who represents the false Church, Archimago, a sorcerer who represents paganistic heresy, who hates Redcrosse and England, and King Arthur and Merlin.

Rather than an allegory, this epic poem is overtly theological, and a masterpiece of explanation as to why God allows people to suffer, how sin began, why Jesus must be the Messiah, etc. Milton enters deep into philosophy many times, especially when God, watching from Heaven, explains that mankind has just committed sin and killed itself by disobeying his law (don’t eat that tree’s fruit). So with Man officially fallen from grace, the Son of God, still in Heaven, having not yet been born mortal on Earth, who has no name, announces to his Father that he will descend into the world of men, become one, and allow himself to be killed to atone for Man’s sin.

Satan, meanwhile, is given one of the most interesting portrayals in literature. He is practically the hero of the poem, from his and his minions’ point of view. They are cast out of Heaven for warring against God. Satan wants to be God, and refuses to quit. Now burning in Hell, he and his minions discuss how to get back at God. Some want more open war. Satan advises against this, and decides on surreptitious treachery: he knows of God’s newest and greatest creation, Man, on Earth, and will travel out of Hell, up to Earth, and corrupt that creation, to make God despair and hate him. How evil!

One of the most fun moments in the poem is a flashback showing the actual war in Heaven. You ask yourself how those already immortal can be killed, but this is not the issue. Satan and his angels fight against Michael and his angels, and whoever is stronger will overpower the other and gain the throne, casting the losers out of Heaven to Hell. Michael and his angels are nearly beaten back to the walls of the Holy City, but are saved at the last moment by the Son of God, who saddles up a chariot of ethereal fire and does what everyone would love to see in a film: Jesus kicking ass. After all, he’s not a tame lion.

The Divine Comedy is the finest work in the Italian language, which is saying a lot. We would be hard-pressed to decide on the greatest work in the English language, or any other language, but Dante has Italian pretty well sewn up. He invented terza rima for the purpose of this epic poem, a rhyme scheme still popular and widespread today. It does a fine job interlocking the 3-line stanzas. The Comedy, as he titled it, doesn’t have one single joke. It’s a comedy in the sense that Dante, the main character, journeys upward from Hell, through Purgatory, to Heaven, and not the other way around. So it has a happy ending and is not a tragedy.

But the most famous Canzon of it, the Inferno, is 34 books of the most awe-inspiringly elaborate, horrifying tortures anyone has devised in fiction. The modern Christian conception of a lake of fire is nowhere to be found. Instead, much more interesting are the punishments Dante devises for the various sinners in response to their particular sins. Hell is in 9 circles, and Dante constructs it as an amalgam of the Ancient Greek and Roman Hells, combined with Christian ideas. Various popes and cardinals are down there, along with all who died before Jesus’s death removed sin from mortal man. The Harrowing of Hell is mentioned near the beginning, after which the Old Testament heroes, such as Noah, Abraham, Moses and King David, are rescued up to Heaven.

The entire poem is a critique of various famous figures from Dante’s time, and antiquity. Some he admired, like Homer, Virgil, Horace, Ovid, and Lucan, are in Limbo. Julius Caesar is there, and Saladin, who was decent and chivalrous. Alexander the Great, however, is eternally boiling in Phlegethon, a river of blood in the 7th Circle. Talk about macabre. And if you’re wondering, yes, lawyers are down there, boiling in a sea of pitch.

For its jaw-dropping brilliance of imagery from page one to page end, and the fact that the reader has been taught quite a few lessons without realizing the work’s didactic nature, Dante must surely secure for his masterpiece the first spot.