Creepy

Creepy  Creepy

Creepy  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

10 Books That Have Been Lost To History

Books are one of humanity’s greatest inventions. A few scribbles on a page and your thoughts, knowledge, and emotions can transcend space and time, allowing anyone who reads them to know exactly what you were thinking and feeling at that moment.

Provided they survive. Unfortunately, books are fragile and the world is a rough place. Below are just 10 examples of some of the greatest books that have failed the test of time.

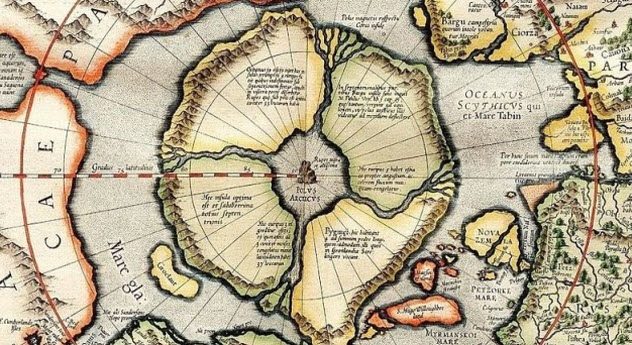

10 Inventio Fortunata

Arctic Logs

In the middle of the 14th century, an unknown monk made a bold and pioneering journey. Setting off from Oxford, England, the monk traveled to the Arctic Circle and became one of the first Europeans to document the area. During his travels, he wrote Inventio Fortunata (“The Discovery of the Fortunate Islands”), which he presented to King Edward III in the 1360s.

Although it is believed that at least six copies of the book were made, all soon faded into the obscurity of history. We do know that the book was verbalized to Jacobus Cnoyen by another monk. Cnoyen, a Flemish author, documented a summary of what he was told and released it as a part of his 1364 book Itinerarium.[1]

Before Itinerarium ultimately went missing as well, renowned 16th-century cartographer Gerardus Mercator got his hands on a copy, which he used as the basis for his atlas published in 1569. In it, he included a full quotation that allegedly described the North Pole:

In the midst of the four countries is a Whirlpool, into which there empty these four Indrawing Seas which divide the North. And the water rushes round and descends into the Earth just as if one were pouring it through a filter funnel. It is four degrees wide on every side of the Pole, that is to say eight degrees altogether. Except that right under the Pole there lies a bare Rock in the midst of the Sea. Its circumference is almost 33 French miles, and it is all of magnetic Stone.

Of course, we know now that the North Pole looks absolutely nothing like that. So did the original maritime monk really exist, and did he travel to the North Pole? If so, were his writings accurately described by the other monk to Jacobus Cnoyen, or did things get lost in translation before reaching Mercator?

Without the original manuscript, we will likely never know the full story.

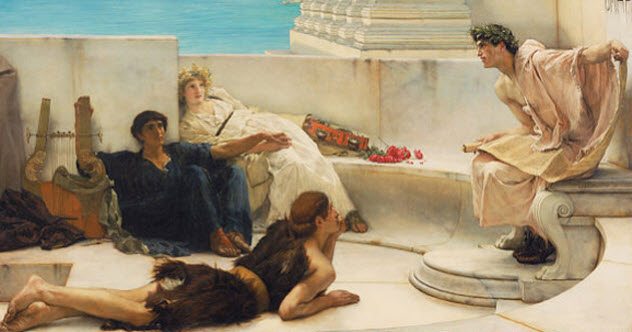

9 Homer’s Margites

First Influential Comedy

There’s something inherently funny about a bungling idiot who can’t get anything right. From the likes of Laurel and Hardy to every American dad in every sitcom ever, idiots are always a good choice in comedy. Maybe it’s because we can relate to their mistakes. Maybe it’s because watching them makes us feel better about ourselves. Or maybe it’s because of Homer’s missing poem, Margites.

Homer (the Greek, not the Simpson) is most famous for writing the poems the Iliad and the Odyssey. These two epics have had an unfathomable influence on writers all over the world and continue to be studied thousands of years after they were written. We can only imagine how influential Homer’s comedy Margites could have been.

Margites was Homer’s first poem, written around 700 BC. We don’t know exactly what kind of journey the main character of Margites went on. But we do get a little insight into his character from Plato, who said that “he knew many things, but all badly.” We also know that Margites wasn’t sure if men or women gave birth and was afraid to sleep with his wife in case she gossiped about how bad he was . . . to his mom.

Aristotle believed that Homer had ushered in a new age of comedy, even saying that Margites was as influential to comedies as the Iliad and the Odyssey were to tragedies. While fragments of the poem remain, such as the opening “comically-oversized-penis-stuck-in-the-toilet” gag, most of this masterpiece has been lost forever.[2]

8 Cardenio

Shakespeare’s Play

At the beginning of the 17th century, a new fad was sweeping across Europe. It was a novel little idea called a novel, and Don Quixote was among the first.

Originally published in Spanish in 1605, the story focused on a man named Cardenio who had heard one too many stories of knights in shining armor and set off on an adventure to become a knight himself. The book was funny, exciting, and tragic. It is also widely considered to be Spain’s primary contribution to the literary world.

When Don Quixote was translated and invaded English stores in 1612, Shakespeare picked up a copy and immediately set to work on a new play: Cardenio. Whether Shakespeare was so inspired by this completely revolutionary piece that he wanted to honor it by using the same name or whether he just hoped nobody who saw the play would have read the book remains unclear—as Shakespeare’s Cardenio disappeared almost instantly.

Few traces remain to prove that Cardenio even existed. Records from the Treasurer of the King’s Chamber show payments for Cardenna and Cardenno, both believed to be misspellings of Cardenio. Copyright records from 1653 show that the play was owned by a man named Humphrey Moseley, but that is the last real shred of proof that the play existed.

In 1727, Lewis Theobald published Double Falsehood, claiming that he had compiled three early Cardenio manuscripts into one play. Fast-forward to today, and a man named Gary Taylor has spent almost 30 years combing through Double Falsehood. He was trying to carefully identify which bits were written by Shakespeare and his collaborator John Fletcher and which were inserted by Theobald.[3]

Although some experts believe that there are passages that can be attributed to Shakespeare, you need to suspend a lot of disbelief to accept that one man had three original copies of a lost Shakespearean play. We are unlikely to ever know just how much, if any, of this play survived.

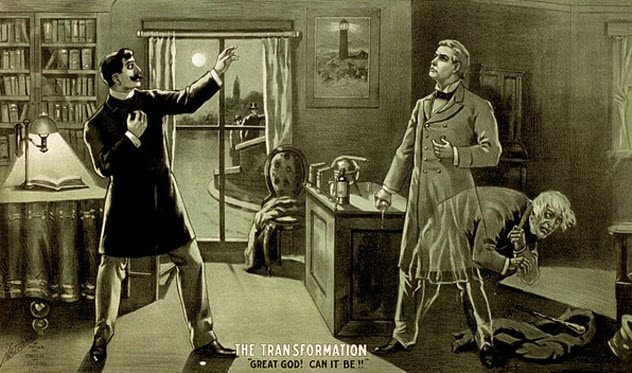

7 Jekyll & Hyde

First Draft

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde is one of the most famous horror stories ever written. The story examines the nature of the inner battle waged by humans between good and evil as well as their conscious and subconscious desires.

In fact, the book has made such an indelible mark on Western literature and culture that “Jekyll and Hyde” is now a commonly used phrase. But if Fanny Stevenson had not been such a harsh critic, you might never have heard of her husband, Robert Louis Stevenson.

Letters discovered in 2000 between Fanny and family friend W.E. Henley revealed that Fanny believed the book was simply bad, describing it as “utter nonsense.” She felt that the draft was a messy story about a scientist who turned into a monster, but it had no real purpose or message behind it. She suggested that the transformation should be used to symbolize the conflict of human nature, the theme for which the book is now most famous.

The original idea for the story came to Stevenson while he was in the midst of a cocaine-induced nightmare. Indignant that Fanny woke him up from his distressed sleep, Robert set to work writing the 30,000-word draft over the course of just three days.

This is the draft to which Fanny referred in her letter. She signed off by stating, “He said it was his greatest work. I shall burn it after I show it to you.”[4]

And burn it she did, much to the chagrin of her husband. He immediately set to work on it again, this time with the helpful criticism of his wife in mind. The reworked version was completed and became a roaring success, saving the family from their financial woes.

But while you can pick up a copy of the revised book in almost any bookstore, the original, terrible draft is gone forever.

6 World War I Novel

Ernest Hemingway

In December 1922, Hadley Hemingway was packing her bags in Paris to join her husband, Ernest, in Switzerland. Ernest was working as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star. After covering the Peace Conference in Geneva, he was due to travel to Chamby.

There, the married couple was to meet with Lincoln Steffens, an American reporter and author they had just met. Like a good, forward-thinking wife, Hadley packed up a number of Ernest’s unfinished manuscripts to show to Steffens and went on her way.

After boarding the train at Gare de Lyon, she decided at the last minute to buy a bottle of water for the trip. When she returned, the bag with the manuscripts was gone.[5]

After what was presumably one of the worst train rides in history, Hadley arrived and had to tell Ernest the truth. He later described the moment by saying that he had only seen people so distressed if they had experienced the loss of a loved one or unbearable suffering. As she struggled to find the words, he assured her that nothing could be so terrible.

When Hadley did tell him, Ernest was understandably panicked. He got someone to cover his job in Geneva and went straight back to Paris. Back then, writers inserted carbon paper between their pages that also absorbed the ink, so the writer effectively wrote two copies at once (sort of like police tickets).

This carbon copy was a writer’s security, the kind of thing you keep in a fireproof box in a separate building. And Hadley had just happened to pack up those as well.

The loss of so many works is one from which Ernest never fully recovered. He never tried to replicate them, instead moving on to other works. Ernest ultimately divorced Hadley five years later.

Ernest Hemingway ominously said that he remembered what he did the night he realized they were gone, but he never elaborated on what that was.

5 Double Exposure

Sylvia Plath

Sylvia Plath was one of the 20th century’s most influential writers. Although the majority of her work is poetry, Plath is perhaps most famous for her semiautobiographical novel, The Bell Jar.

Even so, Plath was not enamored with the book, describing it as “a pot boiler, really.” But she did not feel the same about her unfinished novel Double Exposure, which she described as “hellishly funny.”[6]

Plath began writing Double Exposure, also tentatively titled DoubleTake or The Interminable Loaf, in 1962. By February 11, 1963, she had taken her own life, leaving behind 130 pages of the unfinished manuscript. What happened next is a matter of debate.

Those who had seen the outline for the book claimed that it was also semiautobiographical. This time, the book focused on a woman who found out that her husband was having an affair, much like Plath did. She had separated from her husband a short while earlier.

The estranged husband, Ted Hughes, admitted to burning one of her journals to protect her kids. But he made no such confessions about this book. He claimed to have heard some vague rumors about an unfinished book but assumed that Plath’s mother had stolen it.

Just who is telling the truth remains unclear, but there is hope that the manuscript could surface again one day.

4 On Sphere-Making

Archimedes

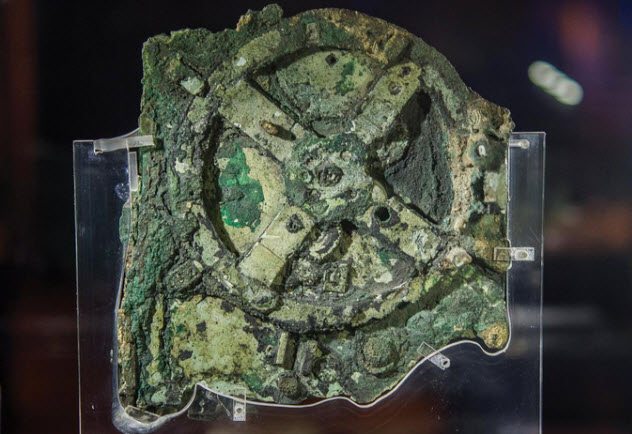

Remember the Antikythera mechanism? The machine found in a shipwreck that was eons ahead of its time in accurately calculating the movements of the stars and planets?

The device was so futuristic that we still don’t fully understand how it was made. Partially, this may be because we have lost what has been described as the most practical of works from the great Archimedes.

He died in Syracuse in 212 BC when the Romans invaded and looted the city. About 100 years later, Cicero wrote of two spheres built by Archimedes: one that mapped the stars and another that mapped the motion of the planets, Sun, and Moon as seen from Earth.

They were incredibly advanced and accurate machines. The designs were possibly laid out alongside those of the Antikythera mechanism in a book titled On Sphere-Making.[7] In this book, Archimedes laid out his theories, formulas, and designs for building such advanced machinery.

Unfortunately, the manuscript was lost when Syracuse was invaded. It is possible that it was looted or even burned by the invaders. Alternatively, it could have been hidden or destroyed by Archimedes himself, who famously spent his last moments in life asking his killer not to interrupt him while he drew circles in the ground.

Whatever became of the book, its potential influence cannot be underestimated as we continue to struggle today in understanding how the ancient Greeks built such complex devices.

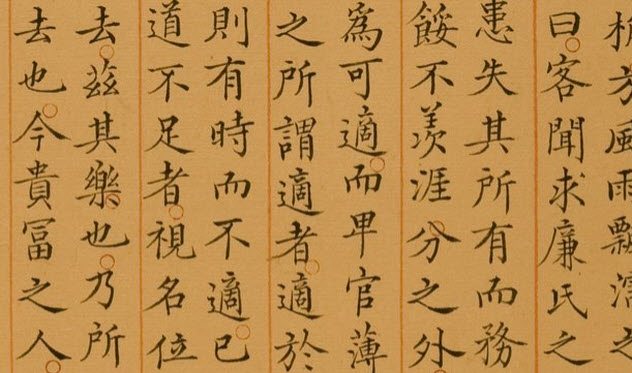

3 The Yongle Encyclopedia

Ming Dynasty

About 1,000 years before Europe invented paper, the Chinese were writing away. Between the 11th and 14th centuries, they kept the secret of gunpowder to themselves. About 700 years before Gutenberg invented the printing press, the Chinese had a thriving printing economy.

Basically, ancient Chinese knowledge was both invaluable and centuries ahead of its European counterparts. This is why Emperor Yongle ordered the production of the Yongle Encyclopedia in 1403.[8] A compilation of over 8,000 Chinese texts—from medicine and science to culture and music—the encyclopedia was an ambitious attempt to compile literally all Chinese knowledge in one place.

The full collection included almost 23,000 scrolls across 11,095 volumes. To store it would require 40 cubic meters (1,400 ft3), and the index alone was 60 volumes long. When the encyclopedia was completed in the early 1400s, the emperor had it stored in the Forbidden City.

After a close call in 1557 that almost resulted in the loss of the collection, another copy was produced. This is a miracle for us because about 400 volumes of this copy still survive today.

The other volumes of both the copy and the original have been lost to history. Most experts believe that it was destroyed when the Ming dynasty was overthrown. However, some have suggested the encyclopedia may have been sealed in the tomb of Emperor Jiajing.

Only three of the Ming dynasty tombs are open, and Jiajing’s is not one of them. His tomb is unlikely to be searched in the near future. So while the answers to so many of our questions could be right within our reach, don’t expect to find them in your lifetime.

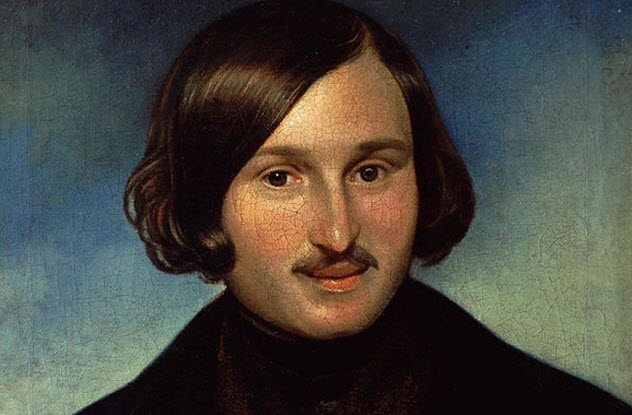

2 Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Gogol is viewed as one of the first and most influential writers in the Golden Age of Russian literature. Born in what is modern-day Ukraine, Gogol was a paranoid hypochondriac who feared death and regularly fell ill. Gogol produced his best work when he was healthy and became essentially immobile during his down periods.

His most famous work, Dead Souls, was based on Dante’s Inferno and aimed to create a piece of work that emulated Russian morality. Upon its release, Dead Souls caused quite an uproar due to its controversial and explicit passages.

The religious community lashed out at Gogol, who took the attacks quite personally and attempted to make amends. This is how he became involved with Father Matvey Konstantinovsky, a religious leader who convinced Gogol that his work was sinful.

Konstantinovsky encouraged Gogol to renounce his work and burn whatever remained. Convinced that his immoral behavior was the cause of his illnesses, Gogol complied and burned the second part of Dead Souls, which was near completion. He instantly regretted this decision and fell into a deep depression. After nine days without food, Gogol died.[9]

1 Lost Mexican Codices

Despite leaving behind many fabulous ruins, the Aztec and Mayan civilizations are shrouded in mystery. There are still large gaps in our knowledge of how they lived, who they were, and how they disappeared. This is in part due to the passage of time, but the real mysteries stem from the loss of their codices.

The Aztec and Mayan codices, known collectively as the Mexican codices, were a collection of illustrations and texts that documented the life, history, and culture of their people. Fewer than 30 survive today, and these have been instrumental in helping us understand their language and culture.

Many of these were destroyed by Itzcoatl, an Aztec who led a successful coup to overthrow the emperor. When he was installed, Itzcoatl ordered the codices to be destroyed so that he could rewrite history, literally.[10]

When the Spanish invaded just over 100 years later, they destroyed almost all the Mayan codices. Diego de Landa had brutally attempted to convert the natives to Spanish culture but did not have the authority to do so. As a result, he was forced to go back to Spain and document what he had learned about their history and culture.

His work was also lost but not before other authors had transcribed parts of it. This leaves us with a checkered third-hand account of the lost codices.

Follow Simon on Twitter for more of the same.

Read about more lost books on 10 Ancient Lost Books We Would Love To Read and Top 10 Lost Works of Literature.