Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

10 Human Attributes Found in Animals

As humans, we are not the fastest or the strongest animal. Even our senses are outmatched by many creatures. Birds see better than us, dogs smell better, and many animals have senses that we do not have at all. Sharks feel magnetic fields, turtles sense electricity, and bees see ultra-violet radiation. Elephants can sense a lack of salt in their bodies in much the same way that we feel thirsty. The humble tortoise can outlive us by a hundred years or more. Basic medicine is used by woolly spider monkeys who eat certain plants for birth control and parrots who eat specific clays to cure poison. So what makes us special? Here we look at ten human attributes of which we are rightly proud, and briefly consider which animals share our abilities. Perhaps what makes us special is not any single factor, but the combination of all of these? Or perhaps it is our potential rather than what we already are?

Culture encompasses all behaviors and activities which are not genetically driven and which are found throughout a local population. The arts and humanities, religions, shared attitudes and practices are all facets of culture. The wonderfully wide variety of human cultures around the world is of great interest in itself; however, not all culture is human. For an activity to be deemed cultural, it must not be directly caused by genetics, it must be passed from one individual to another throughout a population, it must be remembered and not forgotten instantly after it has occurred, and it must be passed down through generations. Many primates have their own cultures and traditions, such as the rain dances some chimpanzee groups perform at the beginning of storms. In 1963, a single Japanese macaque monkey discovered the comfort of bathing in a natural hot spring, and since then the practice has spread completely throughout the troop and is still observed today.

Humans experience a wide spectrum of emotions. From anger to grief to frustration to euphoria, we live our lives moving from one emotion to the next. Anyone who has kept a large pet, such as a dog or a cat, will be aware that these creatures experience fear, desire, panic, affection, embarrassment, and many other feelings. Dolphin mothers whose infants have died display all the trappings of grief, and bored octopuses will eventually begin to exhibit depression. Curiosity can be seen in reptiles and jealousy of parental attention between siblings is seen in great apes. Wild apes will adopt other orphaned apes, and captive apes will take pets for interest. Altruism has been shown by gorillas in two unrelated situations where, both times, a young child fell into their zoo enclosure. Each time, a gorilla patted and soothed the child and helped return him to the human zoo keepers. Chimpanzees similarly comfort each other after attacks. Emotions are far from an exclusively human experience.

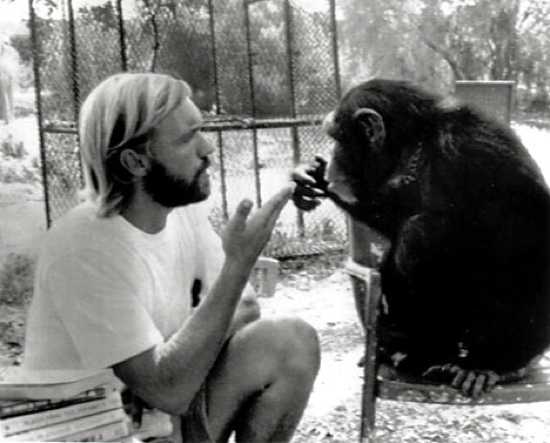

Language is used to communicate needs, wants, and ideas. Different groups have developed their own languages, and languages change and evolve over time. Humans use a wide range of languages, not all verbal. The Bubi people in Equatorial Guinea speak largely with hand gestures, similar to Sign Languages spoken by deaf communities. On La Gomera of the Canary Islands, whistled language is used. Certain animals use language too. Primates, whales, birds, and squid have been shown to use distinct words to identify objects, actions, and individual names, and chimpanzees even use syntax and grammar. As a case study, Washoe the chimpanzee was raised as a deaf human child. She learnt over 350 American Sign Language words and could combine them to form new words and sentences. In the wild, chimpanzees normally only use about 70 signs. Washoe often signed conversations with her toy dolls. One touching example, showing that she could associate abstract ideas like emotion to novel situations, was when her human instructor explained a long absence by signing “my baby died.” Washoe looked down for a while, then signed “cry” and touched her cheek.

Humour is a staple of life for many people. Often difficult to define, there are many strains of humor, providing amusement and often resulting in laughter. The ridiculous, the unexpected, or the juxtaposed can elicit such a feeling. Chimpanzees, like humans, are no stranger to laughter. They often tickle each other and give unmistakable laughs as a result. However, although humor often provokes laughter, laughter does not imply humor. Even rats have been shown to be able to laugh. Nevertheless, chimpanzees too can find situations humorous. Several great apes in captivity have been observed to laugh at situations removed from themselves such as seeing a clumsy fellow ape embarrass itself.

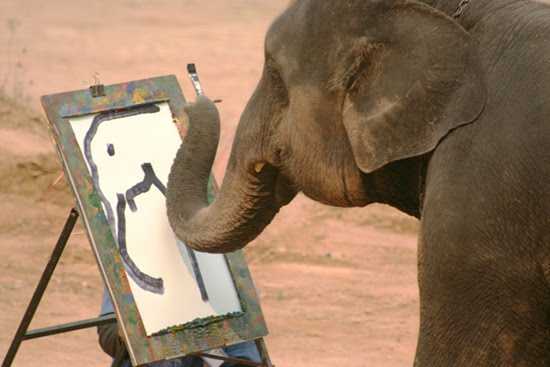

One of the defining characteristics of humans is the ability to use tools. We have created great cities, refined farming, secured the passing on of cultural knowledge through writing, and even gone to the moon. For many years, humans were defined as the only tool-using animal. We now know this is not the case. All great apes, crows and ravens, dolphins, elephants, and even octopuses are verified tool users. Often this tool use is cultural, that is, the tools used and their manner of use will vary from one population to the next within a species. Chimpanzees use stones as hammers and anvils and fashion spears for hunting, gorillas will use walking sticks, ravens make their own toys, gulls will use bait to fish with, dolphins use shells to catch fish in and eat from, octopuses will use coconut shells as a shelter, and elephants make water vessels to drink from.

Humans are able to mentally capture their sensory information at a particular time and store it away for later use. That is, humans can remember things. We use memories to determine the best course of action in situations we have encountered before, such as remembering which foods taste nicest and thus picking the best one when given a choice. Animals, too, have memories, as any pet owner will tell you. Domesticated creatures can be taught to remember commands, and even goldfish have been shown to have memories lasting months. Chimpanzees remember images and numbers better than university students, and crows remember shapes better than adult humans also. Some jays and squirrels have superb spatial memories, allowing them to remember months later where they buried thousands of seeds across areas of dozens of square kilometers. Cats have short-term memories at least ten times longer than those of humans. Interestingly, pigeons seem to base superstitions on their memories. If a pigeon is doing something like turning around when it is given food two or three times, it will remember what it was doing and begin to spin obsessively in the hopes of obtaining more food.

A jellyfish, most will agree, is not strongly aware of itself as a definitively separate being. It has no thoughts, if any, beyond its basic drives. Self-awareness was considered a human domain for many years, but we now know better. One simple illustrative test is the mirror test: seeing if an animal can recognize itself in a mirror. A self-aware animal will realize that the movements of its reflection match its own, and deduce that the reflection is an image of itself. The animal often has a mark on its face, and if it realizes that the reflection is it itself, it will reach towards its face to feel or remove the mark. Human children do not pass this test until the age of 18 months. Animals which pass this self-awareness test, and a variety of other such tests, are all great apes, some gibbons, elephants, magpies, and some whales.

Humans are homo sapiens, the wise man. We can think and reason to our great advantage. There are, of course, many different kinds of intelligence and ways of using them. There exist many definitions of intelligence, but generally it is thought to be the ability to think, reason, plan, assess, and learn. However, humans are not the only animals with intellect, nor are they the best in all its categories. Pigeons easily outdo humans with both visual searching and geometric recognition. Ants estimate huge numbers very accurately to determine the numbers of enemy ants from past encounters, and elephants use arithmetic. Crows show great causal reasoning; they can observe a new and complicated mechanism and mentally deduce how to deal with it correctly rather than relying on the more time-consuming trial and error. They can unlock doors and find hidden objects based on a single period of observation, outperforming many humans.

Farming is the basis of modern human civilization. Believed to have been begun nearly ten thousand years ago, it allowed humans to settle in one place rather than live nomadically as they followed herds of animals for food. This in turn allowed them more time in which they could develop writing, mathematics, the wheel, farming implements, and other necessities of farming on a large scale. This spread around the world rapidly. However, ants had already been farming for millions of years. They capture, herd, raise, and care for the health of groups of caterpillars kept in a special chamber of their nests so that they may use their sugary excretions as a food source, much like we use cows. Termites cultivate fungi to eat which are so specialized they grow nowhere else on Earth.

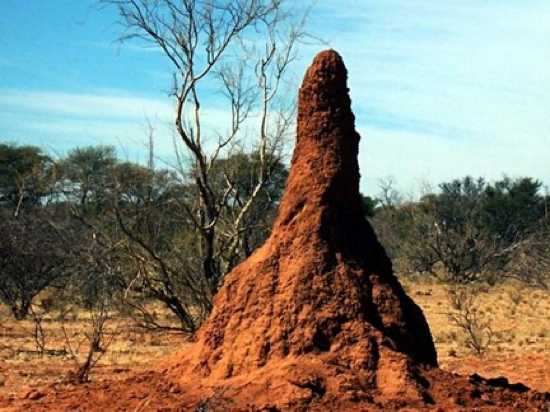

If nothing else, humans are fantastic builders. The cities, roads, and factories that adorn our planet are a testament to that fact. What other animal could build skyscrapers, towering hundreds of metros above them? Or highways and roads stretching for thousands of kilometers? Some animals build too. Certain birds and apes build sophisticated nests, rabbits dig warrens to live in, and ants will even prune and cultivate trees to grow in a way which suits them as a home. The greatest builders, however, are Nigerian termites. They build fantastically huge mounds with internal ventilation, heating, and cooling systems through specially designed tunnels so that the termites living inside enjoy a pleasant climate at all times. They even have self-contained nurseries, gardens, cellars, chimneys, expressways, and sanitation systems. A termite is less than half a centimeter long yet its mound is 4m tall. For comparison, that is like a group of humans making a building over 1.5km tall.

To clarify, abstract thinking is not random and incoherent thought. It means taking a concrete idea, such as an apple, and thinking about an attribute of it as a higher concept such as deliciousness, which might then be applied to many concrete objects. Logical thinking is the cornerstone of this. This is naturally difficult to measure in non-humans, but thus far no animal has been able to perform nearly as well as humans in purely abstract terms. Logical and reasoned thinking with abstract ideas are the great achievement of humanity, as we far surpass other animals thanks to the frontal lobes of our brains, which relative to the rest of our brains are the largest of any living species. Perhaps what truly makes us human is our ability to think rationally, to question our own assertions and consider others, and to always strive for what is reasoned and logical and true, no matter what that truth may be.