Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Most Important Board Games In History

For thousands of years, board games have been a source of entertainment for people across the world. Evidence of board games pre-dates the development of writing—and in many cultures they have even come to have a religious significance. What is particularly striking about a number of these games is how their original ethics and morals have been stripped by big business realising they could make a quick buck off them. Here are ten of the most important board games from ancient and modern history:

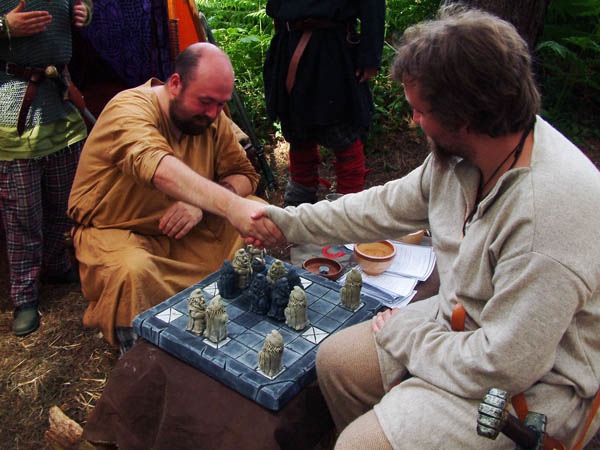

Tafl was a very popular game among the Vikings. One player aims to get his king from the centre of the board to the edges, while the other does everything he can to capture him. Tafl spread across Europe (just like Viking genes) and became the chess of its day; noblemen would boast of their skill on the board.

Tafl was the inspiration for the game Thud, based on Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series. There is still the occasional World Championship—but the fact that these take place on an island with a population of eighty-six makes me doubt how much of a “world” championship it really is. A bit more pillaging may be in order.

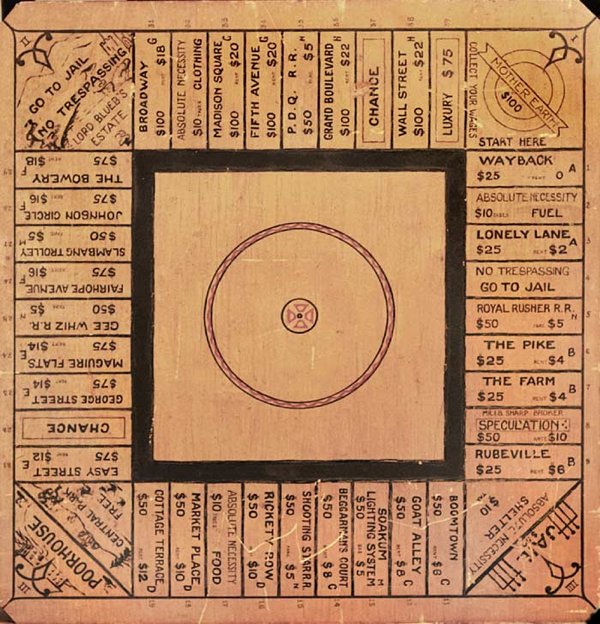

The Landlord’s Game was invented in 1903 by Maryland actress Lizzie Magie. The game board consisted of a square track, with a row of properties around the outside that players could buy. The game board had four railroads, two utilities, a jail, and a corner named “Labor Upon Mother Earth Produces Wages,” which earned players $100 each time they passed it.

This should all sound quite familiar: the fact is, The Landlord’s Game was patented three decades before Charles Darrow “invented” Monopoly and sold it to Parker Brothers.

The Landlord’s Game—later known as Prosperity—was intended to illustrate the social injustice created by land ownership and “rent poverty.” It also offered a solution to this injustice: players could opt to have rent from properties they owned paid into a communal pot, which would then be shared out, making things better for everyone.

The great irony of the story is that when the idea was stolen by Darrow, the prosperity-for-all ideal was removed completely—and the game that went on to be played by more than one billion people ended up encouraging them to make their opponents bankrupt.

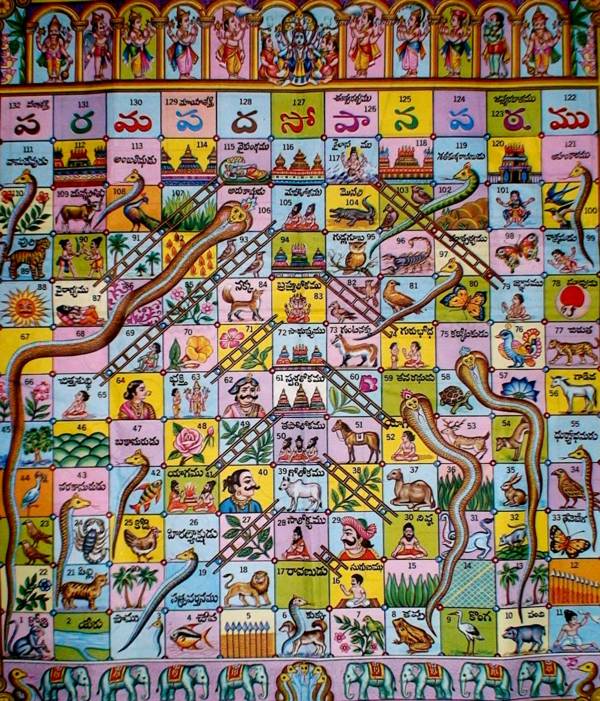

The sixteenth century Indian game of Vaikuntapaali—also known as Leela—was a tool for teaching morality and spirituality. It was the game that went on to be launched as Chutes and Ladders in America (and Snakes and Ladders elsewhere). In the original version, the climbing of a ladder was supposed to show players the value of good deeds in the search for enlightenment; the chutes—or snakes—were meant to show that vices such as theft and murder would bring spiritual harm to the sinner.

The Victorians altered the moral teachings when they brought the game to England in the late nineteenth century. Although in the original one could achieve a state of eternal Nirvana, the British fondness for understatement meant that in the Western version, one simply achieved “success.” By the time Milton Bradley brought it to America in 1943, all anyone really wanted was a bit of distraction (something must have been weighing on people’s minds in the early 1940s), and so the game became what it remains today: a basic race to the finish.

A precursor to Tick-Tack-Toe, Nine Men’s Morris is a game in which counters are placed on a grid with the aim of creating lines of three. Once all the pieces are down, they can be moved one space per move. Whenever a player forms a row of three, he can remove one of his opponent’s pieces from the board. The first player down to two pieces loses.

The simplicity of the game board meant that people across the world could create their own without much hassle. Boards dating as far back as 1440 B.C. have been found carved into steps and rocks in Sri Lanka, Bronze Age Ireland, ancient Troy and the Southwestern United States—note to Mormons: this is not archaeological evidence in support of the Book of Mormon.

Not content with scarring the landscape alone, it seems that fans through history carved the board into seats, walls, and even tombstones across England. For all the concern over World of Warcraft, we’ll know computer game addiction has become truly serious when people start vandalizing their nearest graveyard for a quick fix.

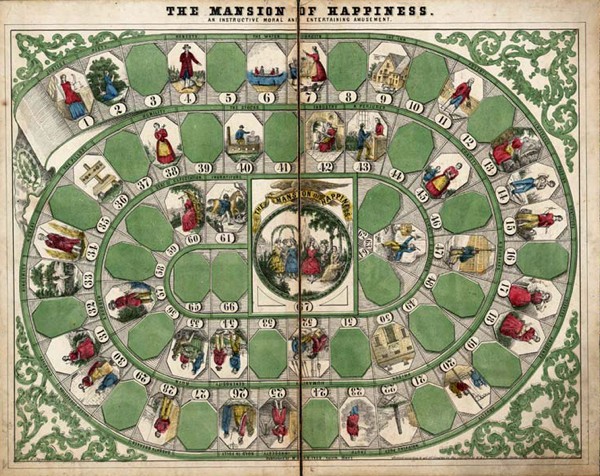

When Parker Brothers republished The Mansion of Happiness: An Instructive Moral and Entertaining Amusement in 1894, they claimed that it had been the first board game published in the US—way back in 1843. The game was in fact probably the second game published in the US; but it is still noteworthy as a successor to the “race to the afterlife” theme common in many older religious games.

The game designers had to use technicalities to get past the the then-sinister connotations of gambling (a six-sided die is Satanic, a six-sided spinner not so much). The board consisted of a basic roll-and-move track—saturated with more Puritanism than should rightfully fit on a piece of cardboard. Sabbath-breakers are sent to the whipping post (whips sold separately), and the vice of Idleness will land you in Poverty. The game also includes what is perhaps the worst rule ever prescribed in the history of board games, with a player sometimes required to wait “till his turn comes to spin again, and not even think of happiness, much less partake of it.”

Luckily, “do not partake of happiness” is a rule that didn’t really catch on.

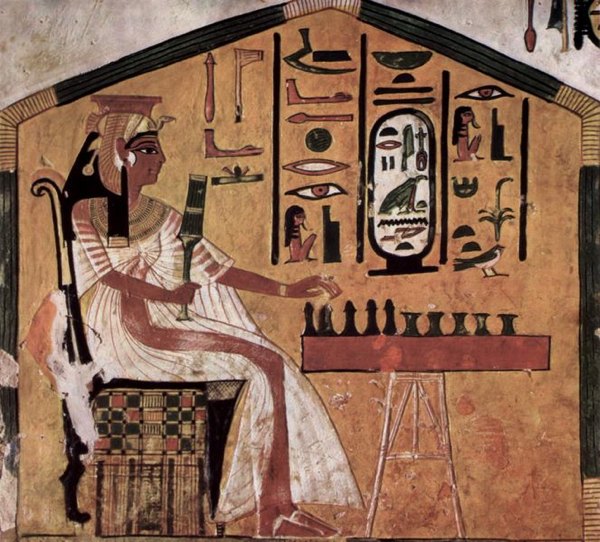

Senet is the oldest board game known to exist. Sets have been found in burial chambers from as far back as 3,500 B.C.—including four in Tutankhamen’s tomb. Game boards were three squares wide and ten squares long, and sets typically had five to seven pieces for each player. Though the original rules have been lost, there is general consensus that the aim is to race one’s pieces across the board, using thrown sticks as an equivalent for dice.

Though it began as a secular form of entertainment, Senet soon took on a religious significance for the Egyptians. The squares were marked with various symbols representing the gods and other aspects of the afterlife. When you play modern board games, the best you can hope for is entertainment; but players completing Senet “ritually joined with the sun god while still alive and thus assured their survival of the ordeals of the netherworld even before dying.” Handy.

Mancala refers to a family of games with the same basic method of play. Known as count-and-capture games, there is some evidence to suggest that they may be the earliest games played—predating even Senet but further verification is needed. To play the game, all you need is a patch of soft ground and a handful of seeds or pebbles. Rows of holes are dug alongside one another, and players distribute counters one at a time in a path round the board. There are a number of goals; but the key to victory in every version is basically to count really fast.

Mancala was little-known in Europe and America until relatively recently. A report from the Smithsonian Institute described it as the “national game of Africa.”

The Indian game of Chaupat and the closely-related game Pachisi are the original cross-and-circle games, of which the best known example in the West is the much-simplified Ludo. Players aim to race their pieces around the board, with moves determined by a throw of cowry shells. An opponent’s pieces can be captured by landing on the same square, and two of a player’s pieces on the same square can merge into a “super-piece”.

The Mogul Emperor Akbar I played the game on a giant board, using slave-girls instead of pieces. How two of these “pieces” merged into a “super-piece” is unclear—and a Google search for “slave girl pieces” returns results about, shall we say, other things.

Chaturanga is a game that deserves to be known, if only because of its enormous legacy: chess.

There are few games as widely known as chess. Chess became an extension of the Cold War in 1972; it has ousted all contenders in Europe for the title “Game of Kings”—and the western game is not alone. The Chinese have Xiangqi, the Japanese play Shogi, and there are equivalents in Korea, Thailand and India. Chess is sometimes used as an analogy for life itself, and in the popular mind it is a symbol of genius.

Chaturanga—which dates from as far back as the seventh century A.D.—is the common ancestor of all the modern versions of chess. The board and most pieces are the same, though the exact rules are sadly forgotten. But it seems that the creators of Chaturanga hit upon the formula that would go on to spread the game throughout the world: The pure battle of skill. The almost infinite complexity. The scope for beauty. And the resemblance to much of real life.

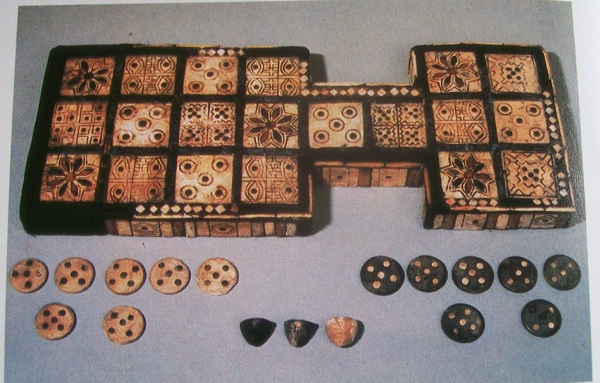

The Royal Game of Ur is the oldest-known board game for which the original rules survive. The oldest sets, discovered in Iraq in the 1920s, date to around 2600 B.C. The Royal Game of Ur is a race game, much like Senet, in which one throws dice to move one’s pawns towards the goal.

The game had been thought long-dead—superseded by backgammon 2000 years ago—until game enthusiast Irving Finkel (who had poetically discovered the game’s rules carved into an ancient stone tablet) stumbled upon a surprising photograph of a game board from modern India. A small amount of detective work later, Finkel met a retired schoolteacher who had played what was basically the same game as a youngster—making this the game that has been played for longer than any other in the history of the world.

You can play it by clicking the link here. As you play, bear in mind that it has outlasted all of the world’s greatest empires, and is older than all the world’s major religions. That’s the power of board games. Don’t let this one die at the hands of the Playstation.

![Top 10 Most Important Nude Scenes In Movie History [Videos] Top 10 Most Important Nude Scenes In Movie History [Videos]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/sharonstone-150x150.jpg)