The Arts

The Arts  The Arts

The Arts  History

History History’s Ten Most Lopsided Battles Ever

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

The Arts

The Arts 10 Iconic Masterpieces Attacked by Pure Pettiness

History

History History’s Ten Most Lopsided Battles Ever

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

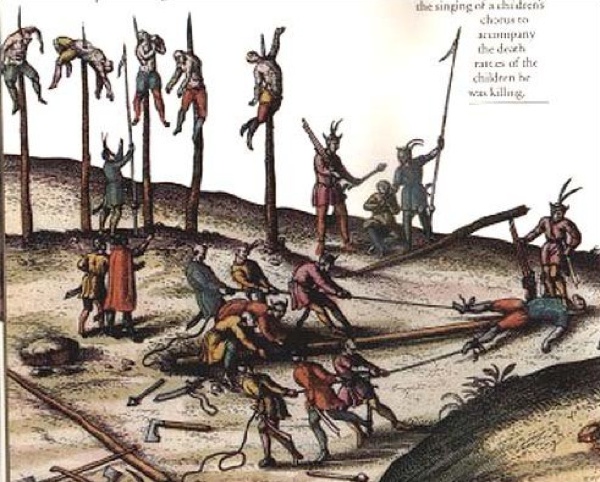

10 Fascinating Facts About The Real Dracula

Bram Stoker’s version of Dracula is one of the most timeless monsters in literature, and one of the first examples of a “classic vampire”—elegant, brooding, and with a thirst for human blood. But despite all the innocent women Dracula seduced and drained of blood, he can’t even hold the stub of a candle to his real-life namesake: Vlad III, or Vlad the Impaler, Prince of Wallachia (now Romania). Here’s why:

The real-life Dracula might not have sucked blood out of his victims’ necks, but he still drank it in a different way: by dipping chunks of bread into buckets of blood drained from the people he killed.

The fifteenth century manuscript The Story of a Bloodthirsty Madman Called Dracula of Wallachia, by Michel Beheim, describes how Vlad III would invite a few guests to his mansion, provide them with a feast, and then have them immediately impaled right there at the dinner table. With the bodies still draped over the stakes, he would leisurely finish his own dinner and then dip his bread into the blood collecting below the bodies.

He didn’t just murder them—he had them all excruciatingly killed by slowly driving blunt stakes through their abdomens. See, Vlad III had spent much of his early life in a Turkish prison, and when he was released he discovered that his father had been betrayed by his people and buried alive by Hungarian troops.

He knew that many of the noblemen that had served under his father were involved in the betrayal; but since he didn’t know specifically which ones, he invited all of them—about five hundred in total—to a feast at his house. Once the feast was finished, Dracula’s soldiers rushed into the room and impaled every single nobleman present.

Dracula went on to use that tactic countless times. He would lure people to his house with a feast, and then kill them. Eventually people knew what it meant to be invited to one of Dracula’s feasts, but they showed up anyway—because if they refused, they’d be killed on the spot. That’s what some call a lose-lose situation.

The word Dracula wasn’t something that Bram Stoker made up for his book; Vlad III actually preferred to be called that. His father, Vlad II, was a member of a secret society known as the Order of the Dragon. He was so proud to be a member that he had his name changed to “Dracul,” Romanian for “Dragon.”

Vlad III also got involved in the Order as a child, which prompted him to change his own name to Dracula, or “Son of the Dragon.” (Although now it means something closer to “Son of the Devil”). Either way, it was a pretty frightening name at the time, especially since the guy had the reputation of, you know, killing everybody he met.

Life for Dracula wasn’t all work, work, impale, work. Nope—according to most sources at the time, he thoroughly enjoyed all that impaling and skinning and boiling alive. In fact, you could even go so far as to say he had a sense of humor—at least, he was known to make some incredibly morbid jokes about his victims as they died.

For example, one account in the book In Search of Dracula describes how people would often twitch around “like frogs” as they died via impalement. Vlad III would watch and casually remark, “Oh, what great gracefulness they exhibit!”

Another time a visitor came to his house, only to find it filled with rotting corpses. Vlad asked him, “Do you mind the stink?” When the man said “Yes,” Vlad impaled him and hung him from the ceiling, where the smell wasn’t quite so bad.

It’s easy to think of Dracula as a solitary madman, just running around killing people, but that’s not how it was. The man just so happened to be the Prince of Wallachia, and many of his “murders” were his own twisted form of law and order. The thing is, impalement was pretty much the only punishment—whether you stole a loaf of bread or committed murder.

Of course, there were exceptions. One account describes a gypsy who stole something while traveling through Dracula’s lands. The Prince had the man boiled, and then forced the other gypsies to eat him.

In an attempt to clean up the streets of the city of Tirgoviste (the capital of Wallachia), Dracula once invited all the sick, vagrants, and beggars over to one of his homes, under the pretext of a feast (you know where this is going). After they had eaten their fill, Dracula politely excused himself and had the entire court boarded up, then burned the whole building to the ground while everybody was still inside.

According to the report, not a single person survived. Evidently Dracula did this quite a bit, sometimes burning whole villages within his province for no apparent reason.

One result of all the killing was that Vlad III effectively had complete control over his people—and he definitely knew it. To prove how much his citizens feared him, Vlad III placed a cup made out of solid gold in the middle of the town square of Tirgoviste.

The rule was that anybody could drink out of it, but it could not leave the square under any circumstances. It’s believed that during this time about 60,000 people lived in the town—yet during his entire reign, the priceless cup was never touched, even though it was in full view of thousands of people living in poverty.

In the 1400s, the region of Wallachia was under constant threat from its neighbors, the Turks. Vlad III, who didn’t like being pushed into a corner, sent an army to push the Turks out of his land.

Eventually, though, the Turks forced Vlad into a retreat—but Dracula was not done. As he retreated, he burned down his own villages along the way so that the Turkish army would have nowhere to rest. He even went so far as poisoning his own wells and murdering thousands of his own villagers, just so that the incoming Turkish army wouldn’t have the satisfaction.

Historians put the deaths at the hands of Dracula at somewhere between 40,000 and 100,000. The man breathed death and then (literally) ate it for dinner. When the Turkish army got to Targoviste, they found the infamous “Forest of the Impaled”—20,000 Turkish bodies displayed on stakes.

This single paragraph from In Search of Dracula could probably sum up most of the stories: “Also as the day came, early in the morning, all those whom he had taken captive, men and women, young and old, he had impaled on the hill by the chapel and all around the hill, and under them he proceeded to eat at a table and get his joy in this way.”

Dracula died on the battlefield fighting against an invasion of Turks. His reputation finally caught up with him in a bad way: his army was outnumbered by Turks, so most of his soldiers just switched sides after seeing that the impalement ratio in the other army was significantly lower. His head was chopped off—possibly by his own troops, which would not be surprising—and the head was sent to the Turkish Sultan, who impaled it on a spear and hung it outside his palace.

Reports state that Dracula’s body was then buried at a cemetery in the Snagov Monastery, outside Bucharest. But there are conflicting reports; some that his body has never actually been found there, while others say that his possible remains were indeed found, but then disappeared. It’s pretty likely that his body was just robbed at some point; as royalty, he would likely have been buried with treasure, making his grave a good target for grave robbers. And then there’s the other theory about why his body was never found: because he’s Dracula.

Eli Nixon is the author of Pretty Bird: A Sci-Fi Novella on Amazon.