History

History  History

History  Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

10 Significant Recent Evolutionary Discoveries

The theory of evolution via natural selection completely transformed the world of science 150 years ago and its ramifications rippled across all aspects of life, including politics and religion. It is as well accepted in the world of biology as the Earth orbiting the Sun is in astronomy, but is perhaps the most socially divisive issue in science. Whilst the reality of evolution is well known there is a lot of detail to figure out in its 3.5 billion year history. These are ten of the most important discoveries from the last decade that are helping science fill in the picture.

Discovery: Butterfly supergenes demonstrate unknown method of inheritance

The butterfly species Heliconius numata has long proved a mystery. Its population carried seven different discrete wing-patterns, each specified by a combination of many different genes. When parents with different wing patterns mate genes get shuffled and spread out and these patterns should quickly merge together. The traditional Mendelian inheritance model we all learned in school breaks down where multiple genes are involved.

A team of British and French biologists discovered in 2011 the presence of what they called a supergene, a cluster of eighteen genes passed down in a single unit. Rather than having a mixture of genes from each parent, offspring inherit particular dominant and recessive supergenes, allowing the discrete trait to carry on. The butterfly holds other mysteries, such as why seven patterns are used to scare off birds, when one would normally suffice, but at least the how has been cracked.

Discovery: Human and chimp interbreeding

It’s well known that chimpanzees are humankind’s closest surviving relative. Crossbreeding the two species has captivated the imagination for over one hundred years [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humanzee] and theories abound about attempts by Soviet scientists. There are some that believe a human-chimp hybrid named Oliver survived until last year, though DNA testing has proven he was just a normal chimp that displayed human-like traits.

Luckily for many of the internet’s quirkier inhabitants, genetic analysis from 2006 suggests that human and chimpanzee ancestors continued to interbreed after their initial split 6.3 million years ago. In fact, it was apparently so hot they saw fit to keep at it for 1.2 million years. These results were unexpected and might open up a new avenue of exploration into the history of life. As study author David Reich explained, “That such evolutionary events have not been seen more often in animal species may simply be due to the fact that we have not been looking for them.”

Discovery: Decades-old bat mystery finally solved by intriguing fossil

Bats are the second largest order of mammals, accounting for a fifth of all mammalian species. They’re the only mammals to have developed full flight and can use echolocation to a level unmatched by any other land-dwelling creature. These archetypal traits have been the subject to a longstanding mystery within biology—which came first? (For the related question, it’s apparently the chicken).

A pair of fossils discovered in Wyoming in 2003, part of a new species dubbed Onychonycteris finneyi, has many odd features. It has claws on all five fingers, compared to the one or two found on modern bats, possibly as an adaptation for climbing in the forest canopy. More importantly it has the capacity for flight without the ability to echo-locate, confirming flight came first. Joining the dozens and dozens of other transitional fossils completely invisible to creationists, the fifty-two million year old specimen ends decades of speculation amongst scientists.

Discovery: Tiktaalik provides missing link between fish and land animals

One of the most profound transitions in the history of life was the move from water to land. Tetrapod is the name given to the first creatures to leave the water and the name means four limbs. The first tetrapods are the ancestors to all living reptiles, amphibians, birds and mammals. Scientists have long understood that tetrapods evolved from lobe-finned fish, the most famous example of which is probably coelacanth. For a long time, however, there was no evidence to show when the soft fleshy fins began to turn into bony limbs, with estimates all the way from 400 to 350 million years ago.

Tiktaalik, discovered in 2004 in Nunavut, Canada, changed all that. Labelled a missing link, Tikaalik was the first fossil that is still a fish but displayed the beginnings of digits, wrists, elbows and shoulders. It’s about as transitional as a fossil can be. Tiktaalik is as profoundly transitional as a fossil can and was dubbed a fishapod by one of its discoverers. The fishapod nano and fishapod classic remain elusive.

Discovery: Lice offer a new window into the history of mammals

Advances in genetic testing have opened up windows into the past that were undreamed of even fifty years ago. Lice, which have been irritating human scalps for tens of thousands of years, offer a unique method to exploit this. Lice are specialists with claws adapted to their host, so when their particular meal of choice evolves into a new species, the lice follow suit. This precision in lice speciation means that louse family trees based on DNA can be dated precisely with just a few fossils to act as anchors.

DNA testing of lice was done by a (probably really itchy) team of researchers at London’s Natural History Museum, offering implications for our knowledge of the evolution of birds and mammals. The researchers found that bird and mammal lice began to diversify before the extinction of the dinosaurs, suggesting that, contrary to the prevailing theory, mammals may have formed some of today’s major groups before the extinction of the dinosaurs. The alternative but equally awesome possibility is that our lice come from a lineage that used to eat the blood of dinosaurs.

Discovery: Giant amoeba casts doubt on when symmetrical life originated

One of the earliest fundamental traits to evolve in the animal kingdom is that of bilateralism. If you divide a human in two from top to bottom through the middle you will have, for the most part, the same things on both sides. You can halve everything from flatworms to sharks to elephants to find the same mirror image, though you’d have a big mess and questions to answer afterwards, but you’d be demonstrating that bilateral symmetry is found everywhere. Such a key trait has been subject to much speculation as to when it arose and some of the best examples of evidence were 550 million year old sea-floor tracks. The creation of these particular tracks by creatures moving in a straight line was thought only possible by creatures with two halves.

A 2007 discovery by researchers from the university of Texas cast serious doubt on those conclusions. Whilst diving off the coast of the Bahamas (sucky job, we know), Dr Mikhail V. Matz and his team filmed an inch-wide amoeba, a single celled creature, rolling along the sea floor. The creature propels itself by exuding protoplasm, and has a water-filled core to help maintain its shape. It left tracks strikingly similar to those found in fossils, suggesting that bilateralism may actually have developed tens of millions of years later than first thought.

Discovery: The Neanderthal genome project suggests we’re related

Neanderthals are the species that was almost us. There is evidence to suggest they were as intelligent as humans, physically stronger and had developed many aspects of culture before their extinction less than 30,000 years ago. Because they died out so recently it has been possible to isolate their DNA. In 2010 a team from Germany’s Max Planck institute published a draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome less then a decade after the mapping of the human genome was completed.

The sexiest headline picked up on at the time was that one to four percent of DNA in modern humans could be traced to neanderthals, which may be evidence of interbreeding between the two. A paper published last year doubts this conclusion, suggesting a common ancestor as the origin of these shared genes, but the original researcher is standing by the jiggy-with-it hypothesis and has published another paper to support it.

Open questions are the lifeblood of science and this one is unlikely to be definitively settled for some time. The key thing to take away from this, though, is that Neanderthals weren’t too unlike us at all.

Discovery: Lucy’s Baby steals Lucy’s thunder

The most famous early human ancestor is probably Lucy, the 3.2 million year old skeleton found in 1974. Though only forty percent complete, Lucy became synonymous with the birth of humanity. Her species, Australopithecus afarensis, was at the time the oldest one known from the time after we split from our common ancestor with chimpanzees. Yet Lucy’s thunder was stolen by the discovery of another Australopithecus afarensis fossil in 2006.

Though predating Lucy by tens of thousands of years, the new fossil was nevertheless dubbed Lucy’s baby. The child was probably female and believed to have died at around age three. Being a child skeleton makes it extremely rare. It is also more complete than Lucy. The child, who was still at nursing age, will add greatly to our knowledge of human ancestry but it’s hard not to be touched by the descriptions of tiny fingers and a knee cap no bigger than a dried pea.

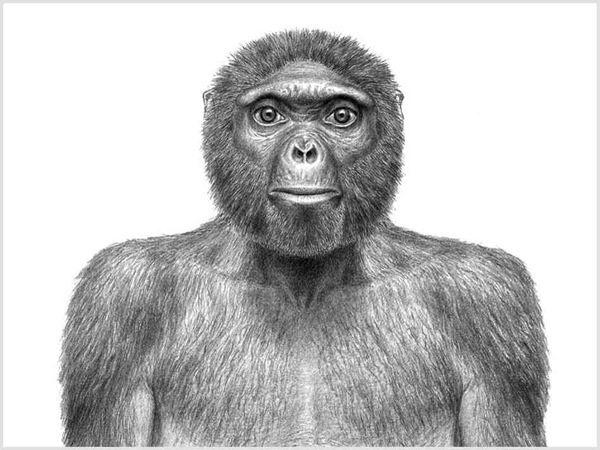

Discovery: Ardi is oldest human ancestor ever found

Whilst we’re on the subject of stealing Lucy’s thunder, meet Ardi, the fossil that stole Lucy’s crown as the oldest known probably human ancestor in 2009. Ardi was a 110 lb (50 kg) small-brained female and she predates Lucy by more than a million years. She was found with the remains of thirty-six other individuals. Part of a new species, Ardipithecus ramidus, Ardi was actually found in 1994 but it wasn’t until 2009, after a decade and a half of painstaking analysis, that the implications became known.

Since the time of Charles Darwin there was a popular notion that our common ancestor with chimps would be like, well, chimps. But chimps have had as long to evolve as we have and there’s no real reason to think our ancestors would be closer to either of us—Ardi casts a definitive blow to the old idea. She shows an unexpected mix of traits both advanced and primitive, unlike chimps or gorillas. As anatomist Owen Lovejoy, who analyzed parts of Ardi, put it, she shows a “vast intermediate stage in our evolution that nobody knew about.” And if there’s one contribution to science greater than any other, it’s a vast anything that nobody previously knew about.

Discovery: Junk DNA isn’t junk after all

When the human genome project’s first draft was presented in 2000, ninety-seven percent of the 3.2 billion bases in the sequence were without apparent function. The primary function of DNA is to provide the designs for proteins, information which is stored in genes, but these constitute just three percent of a DNA strand. Scientists had long known of this noncoding DNA and the description “junk” to describe it was coined way back in 1972. Even noble laureate Francis Crick, co-discoverer of the double-helix, was quoted as saying most of the key to life was “little more than junk”.

In September 2012 the international Encode project published a map of four million switches to be found in junk DNA, switches that regulate the protein-coding genes. Scientists from the project say up to eighty percent of the DNA sequence can be assigned some sort of biochemical function. Less than half a year on, the results of this shift in thinking are already showing: scientists from MIT have identified a portion of noncoding DNA that is fundamental to the development of heart cells, whilst other scientists have found mutations in noncoding DNA that appear to be a key cause of skin cancer. Both of these discoveries have potential medical applications and scientists are likely only scratching the surface.