Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

10 Quarantine Islands and Lazarettos

Throughout history, mankind has feared disease and plagues. One method of trying to combat the spread of disease was to put potentially infectious victims on islands. Back when immigrants and travelers were still arriving en masse by ship, it was common for countries and cities to enact laws mandating the quarantine of sick passengers (or all passengers) of incoming ships before they could reach harbor.

These places of quarantine were called “Lazarettos” or “Lazerets.” All were named after Lazarus, the beggar from the Scriptures. The islands often doubled as leper colonies and sometimes penal colonies. The goal of the Lazaret was simple: isolate and quarantine those who were sick—or thought to be sick—until they recovered, or until they died.

Built in A.D. 1423 on an island in the Venetian Lagoon, Lazzaretto Vecchio was the first lazaretto constructed to quarantine people and care for them during the years of the plague epidemics that ravaged Europe. It served a double purpose, being also a leper colony. Though it consists only of about six acres (2.5 hectares) of land, this lazaretto is now the resting place for untold thousands of people who were buried there—both victims of the plague, and lepers who died after being housed there.

It remained in operation until the seventeenth century. No one knows just how many bodies are buried on the island but at the peak of the plague epidemic it was estimated that up to five hundred people died every day. In 2004, while digging the foundation of a museum, a mass grave of bubonic plague victims, estimated at over 1500 bodies, was discovered. Thousands more are thought to be lying undiscovered on the island.

The Dubrovnik Lazaret was built in 1627 to help prevent the spread of disease as people arrived at the busy port city. Though not an island, this lazaret was a structure built outside the city walls—another common quarantine practice. Between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, Dubrovnik was an important stopping point for traders of the Ottoman Empire seeking to sell their wares to the West.

Dubrovnik is one of the best preserved “walled cities” and the lazaret is one of the few surviving of such buildings in Europe. The Dubrovnik lazaret was one of the most civilized and well-constructed quarantine stations in Europe, and it functioned until the nineteenth century. You can still see the Lazar House today if you visit Dubrovnik, as the structure has been restored and preserved as a heritage site.

Kamau Taurua (appropriately enough, it was originally called “Quarantine Island”) is a thirty-seven acre (15 hectare) island in Otago Harbor, near the city of Dunedin, New Zealand. In the 1800s, as settlers began to arrive in New Zealand in great numbers, the ship Victory sailed into Port Chalmers, New Zealand.

The year was 1863, and the ship was loaded with people suffering from smallpox—a highly infectious and deadly disease. The Victory was not allowed to dock at Port Chalmers, and was instead sent to what would become Quarantine Island. Until it closed in 1924, more than forty other ships had to land on Quarantine Island because they too were carrying sick and infectious passengers. Those who died were buried on the island.

After World War I, veterans who had venereal disease were housed there. Only one of the original quarantine buildings still stands, and today it is protected by the New Zealand Historic Places Trust. The island even has its own song, which begins:

Wind rocks this little land

Anchored between sky and sea

Paused in the drift of time

Cradle of possibility

One of the smallest quarantine or plague islands was a tiny three acre (1.2 hectare) island located in Passamaquoddy Bay, off the coast of Maine. In 1832, this small island was renamed “Hospital Island” and began being used to house and isolate any arriving ship passengers who were believed to be infected with cholera.

A lazaretto was built to house the quarantined. Drinking water had to be shipped to the island. It was busiest during the years of the Great Potato Famine, when ships loaded with lumber from Canada and Maine sailed to Europe and came back loaded with Irish immigrants. Many Irish immigrants died on the passage from Europe or once they arrived at the island, and were buried there.

In 1869, the “Great Saxby Gale” tore into the island, washing away much of the soil, including most if not all of the cemetery. One witness described the waves “washing away the earth from the grave yard and uncovering the coffins,” tearing them open, “exposing the ghastly contents of skull and bones, and in some instances washing them out; even now the curious who visit the Island can see the arm or leg bones sticking out through the soil.”

Later, when bones began washing up on shore in Maine, some school children used the skulls as footballs. The incident was referred to as “A Real Irish Grievance,” and was not settled until authorities reburied whatever remained of the dead. Later, visitors to the island claimed to hear their haunted and ghastly wailings.

Quail Island, located in Lyttelton Harbor near Christchurch, New Zealand, was so named by a ship’s captain who saw quail on the island in 1842 (within thirty years the local quail were extinct). The Maori name for the island is Otamahua (“place where children collect sea eggs”). It was uninhabited until the 1850s, and then in the 1870s it was made into a quarantine island. Immigrant passengers were housed there if they were thought to have been infected with disease before they could reach Lyttelton or Christchurch.

In the late 1870s, children with diphtheria were sent to the island from an orphanage in Lyttelton. Like many lazarets, it was also used as a leper colony. Later the island housed those suffering from the great Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918.

Quail Island also played an important role in the history of Antarctic exploration. Animals used for the famous Antarctic explorations of Robert Falcon Scott, Richard Byrd, and Ernest Shackleton were quarantined there. This included Siberian huskies, Himalayan mules, Manchurian ponies, and Yukon huskies.

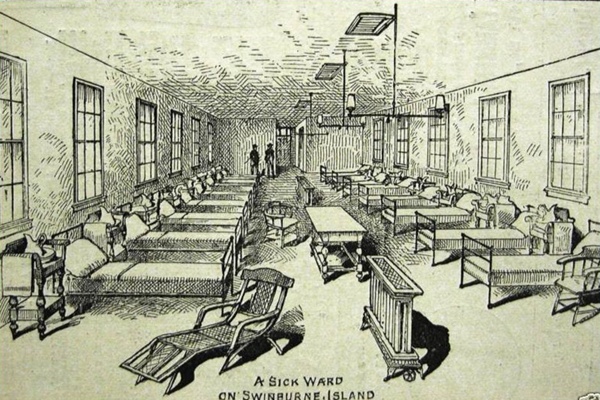

Just off Staten Island in New York Bay, New York, lie two of the better-known quarantine islands. Swinburne and Hoffman islands were both man-made islands built by the federal government after several cholera plagues ravaged New York City in the nineteenth century. As immigrants arrived at the busy Port of New York, they were sent to these islands to be quarantined if they were showing signs of infectious disease. If they were assessed as being healthy, they were allowed to proceed onto Ellis Island and enter New York. The islands were also used to house quarantined patients during the last great cholera outbreak in the United States in 1910.

After World War I, immigration was dropping and better sanitation and means of handling infectious people were developed, so the islands were no longer needed for quarantine. Today, the islands themselves are “quarantined”; the general public is forbidden to visit them.

Located off Crete, the island of Spinalonga was not originally its own island, but rather it was part of the island of Crete. But during the Venetian occupation of Crete, Spinalonga was literally carved out of Crete to make an island fortress. Today the Greek name for the island is Kalydon.

Spinalonga is notable as it was one of the last Leper colonies in Europe. It operated from 1903 to 1957. A priest was its last inhabitant, before leaving the island in 1962. After the island was closed in 1957, this priest had remained behind because as part of the Greek Orthodox tradition, a buried person must be commemorated at intervals up to five years after death.

Sometimes referred to as the “Ellis Island of the West,” Angel Island is the largest island in San Francisco Bay. Over one million immigrants, mostly from the Far East, passed through Angel Island on their way to the United States.

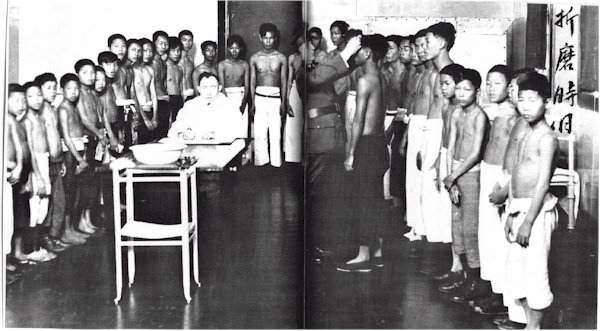

In 1891, a quarantine station was opened in what was then called “Hospital Cove” (today Ayala Cove). The purpose of the quarantine station was to fumigate and delouse arriving immigrants and also detain and house those carrying infectious disease. To facilitate the disinfecting, the US brought in an old wooden slope—the USS Omaha—which used its steam engines to create steam used in disinfecting the immigrants. Large quarters were constructed on her deck for housing the arrivals.

The steamship “China” is an example of the actual quarantine procedure. In 1891 it was the first ship to be sent to Angel Island because passengers had smallpox. Passengers were checked by doctors, than bathed in carbolic acid. They removed their cloths which, along with their baggage, were disinfected in large cylinders using live steam under pressure. The passengers than stayed in barracks for fourteen days. These barracks were disinfected daily with sulfur dioxide and salt water. The ships themselves were disinfected using cyanide or burning sulfur.

On the island of Molokai in the Hawaiian Islands lies the community of Kalaupapa. Located in a peninsula at the bottom of some of the highest sea cliffs in the world (2,000 feet, or 610 meters, above the ocean) the village of Kalaupapa was used as a leper colony for anyone suspected of having leprosy on the islands.

Starting in 1866 and not ending until 1969, Kalaupapa would become the permanent home for over 10,000 lepers. At its peak it housed—as a prison from which there was no escape—about 1200 men, women, and children. Though mandatory isolation of inhabitants was ended in 1969, many (including singer/entertainer Don Ho) lobbied to keep Kalaupapa open, as there was such a stigma around the disease that the Kalaupapans would be treated as, well, lepers, if they tried to live anywhere else.

So although there were actually no active (infectious) cases of leprosy on the island, those who wished to stay were therefore allowed to keep Kalaupapa as their home.

The Great Potato Famine in Ireland in the years 1845-1849 forced thousands of Irishmen to flee their home country. One of their destinations was Quebec, Canada. The Canadian government chose Grosse Island, in the Gulf of St Lawrence, as the island to house Irish immigrants before allowing them to enter Canada.

From 1832 to 1848, thousands of Irish immigrants landed on Grosse Island—and many of them would never leave. Over 5,000 Irish were buried on Grosse Island—a fact which makes it the largest Irish Potato Famine cemetery outside Ireland.

In the year 1847, a massive typhus outbreak killed thousands on the island and aboard the ships. For those passengers lucky enough to get off the ships, perfunctory health checks allowed thousands of desperate and sick immigrants to leave the island and make their way to cities such as Montreal, risking further spread of the epidemic. “Fever sheds” were set up in Montreal to try to isolate these infected and sick people, and it is estimated that as many as 6000 additional victims died there. Incidentally, one immigrant who did make it off Grosse Island safely was the grandfather of Henry Ford.

Patrick Weidinger is a frequent contributor to Listverse. He used to write lists under his pen name, “VanOwensBody”. He lives in Southeast Pennsylvania, USA.