History

History  History

History  Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

10 Lesser-Known Events of the US Civil War

The American Civil War, that is. Call it what you will—the War Between the States, the War to End Slavery—the conflict between the northern Union and the southern Confederacy pitted brother against brother and tore the country apart. Almost everybody knows about the Battle of Gettysburg and Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, but some things aren’t as popularly known as others—except perhaps in trivia questions for military history buffs. Here are 10 Civil War (1861-1865) events which you may not have run across.

Chang and Eng, the 19th century’s conjoined “Siamese” twins, were once drafted . . . almost. Following the brothers’ retirement from show business in 1839, they bought 700 acres of land near White Plains, North Carolina, married sisters, adopted an American surname, fathered children, and owned slaves. According to local legend, in 1865, Union General George Stoneman came to the neighborhood to draft area men into the US Army as conscripts whether they liked it or not. All the names of male residents over 18 were put into a lottery. Eng’s name came up, but not Chang’s. Of course, as soon as he realized “Eng Bunker” was one-half of the famous inseparable duo, Stoneman let him go. By the way, each brother had a son who joined the Confederate cause, and both ultimately survived the war.

Read Edward Everett Hale’s classic, The Man Without a Country? The story was based on the life changing events suffered by a real gentleman, Clement Larid Vallandigham. He was an attorney and Congressman from Ohio, a states’ rights advocate who opposed the federal government’s support of the Civil War as he believed the South couldn’t be forced into rejoining the Union. In 1863, Union Major General Ambrose Burnside issued General Order 38, making it illegal to publicly express sympathy for the enemy. Vallandigham gave a speech criticizing President Lincoln, was arrested under the order, and tried before a military court despite his civilian status—the legality of the trial was debatable. Vallandigham was sentenced to 2 years in prison, but Lincoln avoided a political hot potato by commuting the sentence to banishment to the Confederate states. He eventually returned to Ohio since he still espoused the Union cause (not their policies) and the Confederates didn’t want him either.

Before President Lincoln issued his official Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, Union General John Charles “Pathfinder” Frémont, who’d been put in charge of the Department of the West by the POTUS, issued a proclamation of his own in August 1861. After putting Missouri under martial law due to instances of guerrilla warfare, threat of a Confederate invasion, and general lawlessness, he proclaimed that any rebel sympathizers or Confederates in the state would forfeit all their property, including their slaves, and the slaves would be declared free men and be given deeds of manumission. Lincoln wasn’t pleased. Believing the act unconstitutional, he ordered Frémont to amend his proclamation, and in November, removed him from his position. Frémont was the first, but he wasn’t the last—in May 1862, Union General David Hunter issued a similar emancipation proclamation for Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida. A furious Lincoln ordered the proclamation retracted.

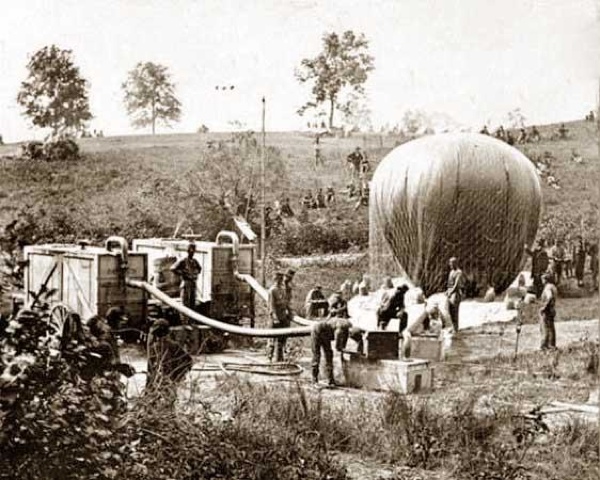

Not recognizing the usefulness of manned balloons for military aerial reconnaissance, the Union Army balked at creating a Balloon Corps, but America’s most famous aeronaut, Thaddeus Lowe, performed an impressive demonstration of tethered flight for President Lincoln in 1861 and the Corps was born. On that occasion, Lowe also sent the first telegram from the air. Beginning in 1862, Lowe in the Intrepid and his fellow aeronauts in other balloons flew successful reconnaissance missions over battlefields in the Peninsula campaign, Seven Pines, Sharpsburg, Fredericksburg, Antietam, and others. Confederate attempts to emulate Lowe and his balloons failed. However, due to a pay dispute and continued strained relations with military commanders, most of whom had no appreciation for balloonists, Lowe resigned as Chief Aeronaut in 1863, which pretty much spelled the end of the Balloon Corps.

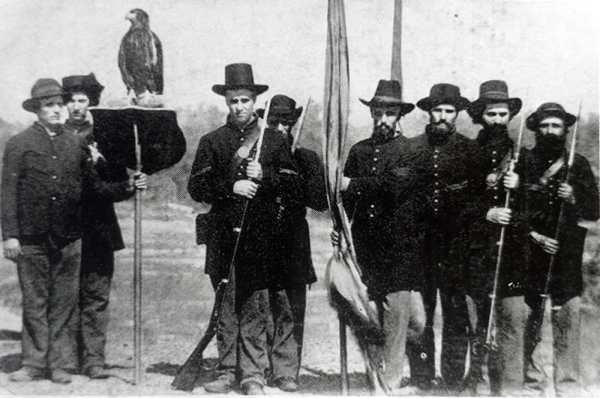

Mascots are a long standing military tradition. Soldiers have adopted dogs, cats, goats, donkeys, monkeys, pigs, birds—but the 8th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment topped them all with the emblem of America itself, a tame bald eagle. The eaglet was taken from the nest and eventually made her way to the 8th Regiment, where she was named Old Abe after President Abraham Lincoln. She became a very popular patriotic symbol of the Union cause. She had a special shield shaped perch, but would walk through the camp stealing food. Old Abe flew over battlefields—39 in total—and although the Confederates had orders to capture her if possible, the eagle got through the war unscathed. After 1865, she was retired from the Army and given a new home in Madison, Wisconsin, in the State Capital building. Unfortunately, in 1881 after suffering smoke inhalation during a fire, Old Abe died. Some controversy exists regarding the bird’s sex, and whether “Old Abe” was one bird or several. That the eagle existed isn’t in doubt due to ample photographic evidence.

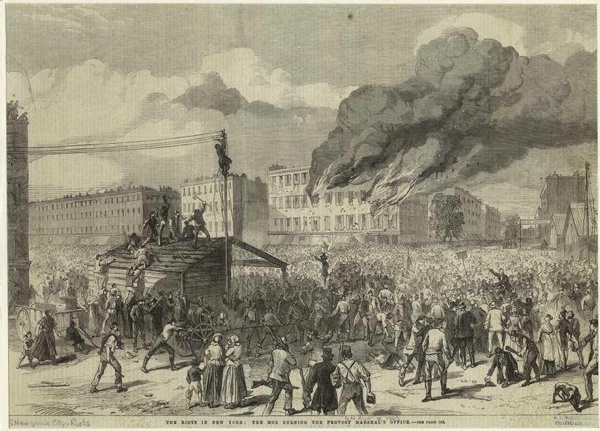

In March 1864, knowing they were on the cusp of losing the war, the Confederacy changed tactics, deciding to launch what we would consider terrorist attacks against New York City. The plan was for a group called the “fire brigade” to set off a series of fires in hotels across the city. These fires were both a diversion and a signal to other groups, who were to take over by force important targets such as the police and municipal buildings, and free the prisoners in Fort Lafayette. It was decided to use incendiary devices fueled by the chemical compound known as Greek Fire, formulated by a southern sympathizer chemist. Had the plan succeeded, it’s possible NYC would have fallen into Confederate hands. But when the time came on November 25, 1864, most of the plotters had no idea how to use the Greek Fire and few fires were set alight. One conspirator managed to accidentally burn down Barnum’s American Museum, but no one was hurt. The Rebel plot was exposed, and the chief architect of the plan to burn New York City was eventually captured, tried, and hung in 1865.

A graduate of the US Naval Academy, Thomas O. Selfridge Jr. fought for the Union side and saw almost constant action during the war. He showed courage under fire as well as an uncanny ability to survive. In his first major battle—USS Cumberland vs. CSS Virginia on March 8, 1862—when crewmen lay mangled and killed by flying splinters and shells, he calmly moved from gun to gun, firing at the enemy while cannonballs sizzled around him. When his ship sank, he swam to shore unscathed. He swam away again when he lost his first command, USS Cairo, to Confederate torpedoes. His next ship collided with another Union vessel and sank. He swam away without a scratch. When the USS Heron went down in 1865 during the naval bombardment of Fort Fischer, North Carolina, Selfridge ended the battle unharmed. The unsinkable officer was eventually given the rank of rear admiral. He retired in 1898. Death finally caught up with Selfridge in 1924. He died at age 88, in bed, on land.

Roswell, Georgia, became the site of a little-known mass deportation of innocent victims of the war between North and South. In the midst of General Sherman’s march to Atlanta, Union Brigadier General Kenner Garrard came to the small town of Roswell, where the local cotton and woolen mills employed 400+ female workers producing “Roswell gray” uniform cloth for the Confederacy. Noting Garrard’s approach, the cotton mill’s owner hoisted a French flag, hoping to avoid his mill being destroyed. The subterfuge backfired. Garrard ordered both mills burned. On Sherman’s direct orders, he took a further step—all the woman workers, black and white, and their children, approximately 700 people in all, were taken under guard to the railyard in Marietta, 10 miles away, where they were herded into boxcars and shipped to Indiana with nothing more than their clothes and 9 days of rations. Sherman ordered a second similar deportation of female textile workers in New Manchester. The women and children were simply dumped in a new city and left to fend for themselves. Most disappeared from history. A few managed to return home after the war.

To be clear, becoming a doctor in the mid 19th century required merely attending lectures at a medical school. There were no official standards. So when war was declared, every physician capable of wielding a scalpel and bone saw was needed—no matter how incompetent, drunk, or just plain sadistic. Dr. Charles Briggs was assigned to the 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry (remember the movie Glory?). On November 6, 1863, Briggs examined Private James Reilly, a black soldier who’d been accused of having sex with a mare. Although he found no evidence, and the private was found not guilty based on Briggs’ testimony, the doctor wasn’t done. For reasons of his own, he had Reilly brought to his tent, stripped naked, bound, and gagged. He circumcised Reilly without anesthetic and cauterized the wound with a hot iron. Briggs was charged with using circumcision as punishment, but never court-martialed for his brutality. A few weeks after the torture of Private Reilly, Briggs was promoted to full surgeon of the unit and served to the end of the war.

When Confederate Captain John Newton Ballard of Mosby’s Rangers lost his leg in battle in 1863, like many of his fellow officers, he didn’t waste time fretting over his amputated limb. Instead, he acquired a second hand artificial leg and got back to war. Unfortunately, he was left literally without a leg to stand on near Halltown, Virginia, when his horse collided with a Union cavalry soldier’s mount and his prosthetic was crushed, making him the only Civil War soldier to lose the same leg twice. However, he was about to have a stroke of luck. In March 1864, Union Colonel Ulric Dahlgren was killed near Richmond, Virginia, during a cavalry raid. He, too, had lost a leg in 1863 (in fact, the severed leg was given a military funeral and is still sealed within the wall of Building 28 in the Washington Navy Yard). Dahlgren’s body was found by Confederates, one of whom took his wooden artificial limb as a souvenir. The Yankee prosthetic made its way to John Ballard, who wore it in active service to the end of the war.