Politics

Politics  Politics

Politics  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Politics

Politics The 10 Most Bizarre Presidential Elections in Human History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

10 Ways Britain Has Ruined the World

“The sun never sets on the British Empire.” Arguably the greatest empire of all time, at its height the British Empire was certainly the largest empire in history, and for nearly two centuries was the foremost global power. By 1922, the British ruled more than 458 million people, and covered 13,012,000 square miles—almost a quarter of the Earth’s total land area.

But in spite of these great accomplishments, the British Empire sowed the seeds for some of the worst disasters that have afflicted humanity. Although the British were not responsible for all of the events directly, their interference in others’ problems was often just as destructive. Here are ten ways the British Empire ruined the world:

Apartheid was a system of racial segregation enforced through legislation by the National Party governments, the ruling party in South Africa from 1948 to 1994. The rights of the nation’s black majority were curtailed, and white supremacy and Afrikaner-minority rule was maintained.

The British did institute some reforms after they seized the Cape from the originally Dutch Boers—such as by repealing the more offensive anti-black Boer laws. But after one hundred years of wars, and having gained complete political control, the British made a decision that doomed many South Africans. They gave Boer republics the green light to disenfranchise all non-whites. The apartheid system was entrenched in the Union constitution, which was drawn and approved by the British government. In 1913, the Native Land Act was brought into force; it pushed black people off the land on which they were either owners or tenants, and relocated them to shantytowns in the cities.

Apartheid would not end until the F. W. de Klerk government moved to lift bans on African political parties, such as the Africa National Congress and Pan African Congress. These actions culminated in multi-racial democratic elections in 1994, which were won by the African National Congress headed by Nelson Mandela.

Some things just don’t click until there’s a name and a face behind the story. Discover the personal horror of Apartheid in the controversial Kaffir Boy: The True Story of a Black Youth’s Coming of Age in Apartheid South Africa at Amazon.com!

During the summer of 1845, a “blight of unusual character” devastated Ireland’s potato crop—the staple of the Irish diet. A few days after potatoes were dug up from the ground, they began to rot. Over the next ten years more than 750,000 Irish died from the ensuing famine, and another two million left their homeland for Great Britain, Canada and the United States. Within five years, the Irish population was reduced by a quarter.

The inadequacy of relief efforts by the British Government worsened the horrors of the famine. England believed that the free market, left to itself, would end the famine. In 1846, in a victory for advocates of free trade, Britain repealed the Corn Laws, which had protected domestic grain producers from foreign competition. The repeal of the Corn Laws failed to end the crisis since the Irish lacked sufficient money to purchase foreign grain.

Britain began to rely on a system of workhouses, which had originally been established in 1838, to cope with the famine. But these grim institutions had never been intended to deal with a crisis of such enormity. Some 2.6 million Irish entered overcrowded workhouses, where more than 200,000 people died.

In 1879, the Gardner Machine Gun was demonstrated for the first time. It could fire ten thousand rounds in twenty-seven minutes, and its accuracy was superior to that of the Gatling gun. This impressed military leaders from Britain, and the following year the British Army purchased the gun.

In 1881, the American inventor Hiram Maxim visited the Paris Electrical Exhibition. While he was at the exhibition a man he met told him “if you wanted to make a lot of money, invent something that will enable the Europeans to cut each other’s throats with greater facility.”

Maxim decided to move to London, and began working on a more effective machine-gun. In 1885, he demonstrated to the British Army the world’s first automatic portable machine gun. Maxim used the energy of each bullet’s recoil force to eject the spent cartridge and insert the next bullet. The Maxim Machine Gun would therefore fire until the entire belt of bullets was used up. Trials showed that the machine gun could fire five hundred rounds per minute, and therefore had the firepower of about one hundred rifles.

The British Army adopted the Maxim Machine Gun in 1889. The following year, Austria, Germany, Italy, and Russia also purchased the gun, causing an arms race on the European continent. The machine gun would haunt the British during the Battle of the Somme, when the British suffered 60,000 casualties on the first day. Since its introduction, the machine gun has caused countless fatalities across the world, and has allowed for more people to be killed within a shorter time span.

The British did not start the slave trade or even import the most slaves (both of these dubious distinctions belong to the Portuguese). In the beginning, British traders merely supplied slaves for the Spanish and the Portuguese colonies; but eventually, British slave traders began supplying slaves to the new English colonies in North America. The first record of enslaved Africans landing in British North America occurred in 1619, in the colony of Virginia.

In the 1660s, the number of slaves taken from Africa in British ships averaged 6,700 per year. By the 1760s, Britain was the foremost European country engaged in the slave trade, owning more than fifty percent of the Africans transported from Africa to the Americas. The British involvement in the slave trade lasted from 1562 to until the abolishment of slavery in 180—a period of 245 years. History Professor David Richardson has calculated that British ships carried more than 3.4 million enslaved Africans to the Americas during this time.

In addition to being a major player in the slave trade, the British supported the pro-slavery Confederates during the Civil War. The British needed cotton to fuel their machines; this caused the demand for cotton to skyrocket, which in turn demanded slave labor. If the Confederates had won at the battle of Antietam, the British would have given full support to the rebels, and may even have tipped the Civil War in favor of the Confederates.

And although Great Britain was one of the first nations to abolish slavery, they quickly made up for the loss of human labor by extracting Africa’s raw materials and resources.

Seeing little to gain from trade with European countries, the Chinese Qing emperor permitted Europeans to trade only at the port of Canton, and only through licensed Chinese merchants. For years, foreign merchants accepted Chinese rules—but by 1839 the British, who were the dominant trading group, were ready to flex their muscles.

They had found a drug that the Chinese would buy: opium. Grown legally in British India, opium was smuggled into China, where its use and sale became illegal after the damaging effects it had on the Chinese people.

With its control of the seas, the British easily shut down key Chinese ports and forced the Chinese to negotiate—marking the beginning of what is known as the “one hundred years of humiliation” for the Chinese. Dissatisfied with the resulting agreement, the British sent a second and larger force that took even more coastal cities, including Shanghai. The ensuing Opium War was settled at gunpoint; the resulting Treaty of Nanjing opened five ports to international trade, fixed the tariff on imported goods at five percent, imposed an indemnity of twenty-one million ounces of silver on China to cover Britain’s war expenses, and ceded the island of Hong Kong to Great Britain.

This treaty satisfied neither side. Between 1856 and 1860, Britain and France renewed hostilities with China. Seventeen thousand British and French troops occupied Beijing and set the Imperial Palace on fire. Another round of harsh treaties gave European merchants and missionaries greater privileges, and forced the Chinese to open several more cities to foreign trade.

The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 began the process of carving up Africa, paying no attention to local culture or the differences between ethnic groups, and often leaving people from the same tribe on opposite sides of artificial, European-imposed borders.

Britain was primarily concerned with maintaining its lines of communication with India, hence its interest in Egypt and South Africa. Once these two areas had been secured, imperialists like Cecil Rhodes encouraged the acquisition of further territory, with the goal of establishing a Cape-to-Cairo railway. Britain was also interested in the commercial potential of mineral-rich territories like the Transvaal, where gold was discovered in the mid-1880s.

As a result, during the final twenty years of the nineenth century, Britain occupied or annexed territories which accounted for more than thirty-two percent of Africa’s population, making the British the most dominant Europeans on the continent.

By 1965, Britain had lost its stranglehold on the continent—but the consequences of imperialism were immense. Firstly, the settler states of Kenya, Rhodesia, and South Africa saw many episodes of violence before African nationalists could forge a return to stability, after the departure of the colonial governments. Corrupt African “strongmen,” or dictators, often gained power—despite ignoring the social needs of the people. Economic dependence on the West, coupled with political corruption, crippled attempts to diversify.

Even today, Africa is the least developed region in the world, with poverty and malnutrition running rampant. The idea that Europeans wanted to “civilize” Africa was an utter lie, and a means to justify the exploitation of the continent.

In March 1935, Hitler established a general military draft and declared the “unequal” Versailles Treaty disarmament clauses null and void; some European leaders appeared to understand the danger, and warned him against future aggressive actions.

The emerging united front against Hitler quickly collapsed. Britain adopted a policy of “appeasement,” granting Hitler possibly everything he could want in order to avoid war. The last chance to stop the Nazis without world war came in March 1936, when Hitler suddenly marched his armies into the demilitarized Rhineland, brazenly violating the Treaties of Versailles and Locarno. An uncertain France would not move without British support; and the British refused to act.

The years that followed led to a far stronger Germany. In 1936, Germany, Italy, and Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact. At the same time, Germany and Italy intervened in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Their support helped the Spanish fascists defeat Republican Spain. In 1938, Hitler threatened to invade Austria, and thereby forced the Austrian chancellor to put local Nazis in control of the government. The next day, German armies moved in unopposed, and Austria became part of Greater Germany.

Simultaneously, Hitler began demanding that the German-minority area of western Czechoslovakia—called the Sudetenland—be turned over to Germany. In September 1938, British Prime Minister Chamberlain went to Germany to negotiate with the Nazis. The British and French agreed with Hitler that the Sudetenland should be ceded to Germany immediately. Hitler’s armies eventually occupied the remainder of the Czechoslovakia, in 1939. For Hitler everything was set on September 1, 1939, German armies invaded Poland, and Britain and France finally declared war on Germany. The Second World War had begun; in the next six years more than fifty million people would lose their lives.

Discover more of the behind-the-scenes atrocities—and heroism—that later became the hallmark of this devastating war. Buy Eyewitness to World War II: Unforgettable Stories and Photographs From History’s Greatest Conflict at Amazon.com!

The Industrial Revolution began in England during the 1780s, and started to influence continental Europe and the rest of the world after 1815. It profoundly modified much of the human experience. It changed the patterns of work, transformed the social class structure, and altered the international balance of political and military power, giving added impetus to the ongoing European expansion into non-European lands. The Industrial Revolution also helped ordinary people attain a higher standard of living. But industrialization would have terrible consequences for much of the world.

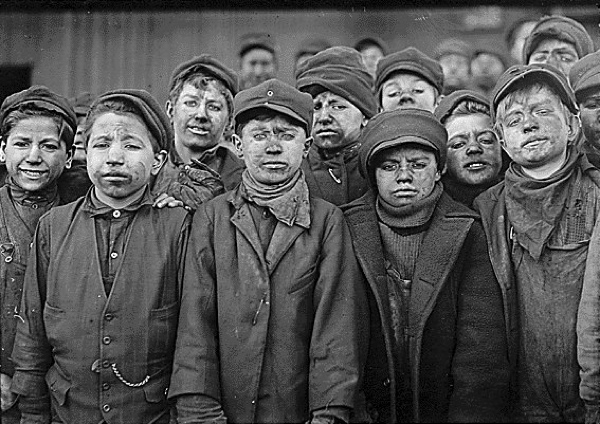

Factory owners became very rich during the Industrial Revolution, while factory workers lived in soul-crushing poverty. Cities grew around factories, often rapidly and without proper town-planning. This often meant that there was no sufficient sewage, running water, or sanitation systems. Ironically, “slums” first originated in Britain, where crowded and filthy settlements were breeding grounds for diseases such as cholera. Factory work was difficult and dangerous, with typical shifts lasting between twelve and sixteen hours. Owners hired women and children because they knew they could pay them less; they worked in the same dangerous factories, for the same long hours.

Aside from the way workers were treated, the industrial revolution had many awful long-term consequences. During the twentieth century, thanks in part to the new world system created by the industrial revolution, the world population would take on huge proportions—growing to six billion people just before the start of the twenty-first century (it has now already surpassed seven billion).

That’s a four hundred percent population increase in a single century. This has put severe strain on the resources available on the Earth. It was coal—a fossil fuel—which packed the furnaces of the industrialization that helped propel human progress to extraordinary levels. But of course this came with extraordinary costs for our environment, and to the wellbeing of all living things. The releasing of fossil fuels into the atmosphere has put mankind into a titanic struggle against climate change, global warming, and the threat of extreme weather.

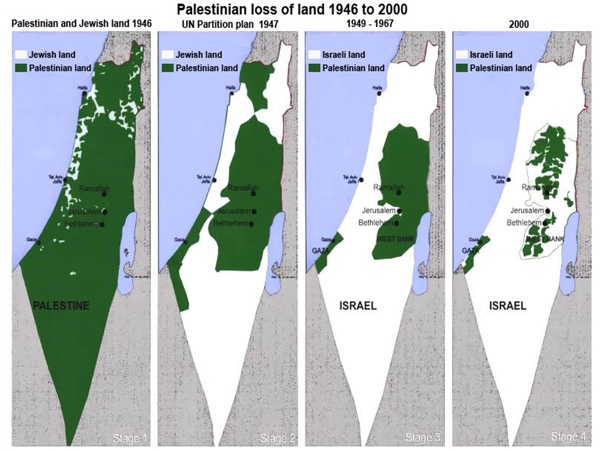

After defeating the Ottoman Empire in World War One, Great Britain did not liberate their Arab allies but instead colonized them. The British received Palestine, Jordan, and Iraq. After centuries of anti-Semitism, many Jews began migrating to their original homeland of Palestine (ancient Judaea), and after the War, these migrations greatly increased. Many British officials, some of whom were also anti-Semitic, wanted to establish a Jewish homeland in the Middle East in order to kick the Jews out of Europe altogether.

The British announced in 1947 their intention to withdraw from Palestine in 1948. On November 1947 the United Nations General Assembly passed a plan to partition Palestine into two separate states—one Arab, and one Jewish. The Jews accepted, but the Arabs rejected the partition. The British officially left on May 14, 1948, without providing a resolution to the situation; that same day the Jews proclaimed the state of Israel. Arab countries immediately attacked the new Jewish state, but the Israelis drove off the invaders and conquered more territory. Roughly nine hundred thousand Arab refugees fled—or were expelled from—old Palestine.

This war left an enormous legacy of Arab bitterness towards Israel and its political allies, Great Britain and the United States. The Arab-Palestinian conflict has provided a deep divide between East and West, and between Christianity and Judaism on the one hand and Islam on the other hand. The modern “War on Terror” stems from the American and Western support of Israel. In addition, Israel has been accused of atrocities ranging from bulldozing Palestinian homes, to acts of terror committed by Mossad, the Israeli CIA.

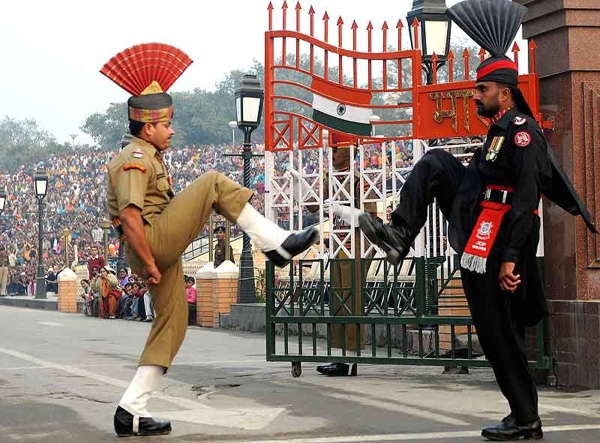

After two centuries of colonialism in India, the British Labour government agreed to a speedy independence of India after 1945. But conflict between Hindu and Muslim nationalists led to murderous clashes between the two communities in 1946. When it became clear that the Muslim League would accept nothing less than an independent Pakistan, India’s last viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, proposed partition. Both sides accepted, and at the “stroke of midnight” on August 14, 1947, one fifth of humanity gained political independence.

Yet independence through partition brought tragedy. In the weeks afterwards, communal strife exploded into an orgy of massacres and mass expulsions. Hundreds of thousands of Hindus and Muslims were slaughtered, and an estimated five million made refugees. Indian Congress Party leaders were completely powerless to stop the violence. “What is there to celebrate?” exclaimed Gandhi in reference to the much-sought independence; “I see nothing but rivers of blood.” In January 1948, Gandhi himself was gunned down by a Hindu fanatic who believed that he was too lenient on Muslims.

After the ordeal of independence, relations between India and Pakistan remain tense to this day. Fighting over the disputed area of Kashmir continued until 1949, and broke out again in 1965-1966, 1971, and 1999. What makes the Indo-Pakistani conflict even more dangerous is that both sides contain nuclear weapons. With the possibility that Pakistan might become a failed state, there is a good chance of a major genocide erupting in the twenty-first century.

Phil Moore is a History Major and filmmaker, who seeks to enlighten the world.