Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Animals

Animals 10 Unusual Wolves That Made The News

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Bizarre, Little-Known Phenomena

Music

Music 10 Musicians Who Changed How Everyone Plays Their Instruments

Humans

Humans 10 Inventors Who Died Awful Deaths in Their Own Creations

Animals

Animals 10 Ways Animals Use Deception to Survive

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Misdirections Directors Used to Manipulate Actors

Politics

Politics The 10 Boldest Coup Attempts of the 21st Century

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Things That Would Have Killed You in the Old West

Books

Books 10 Pen Names More Famous Than Their Authors

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Indispensable Corporations the World Cannot Afford to Lose

Animals

Animals 10 Unusual Wolves That Made The News

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Bizarre, Little-Known Phenomena

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Musicians Who Changed How Everyone Plays Their Instruments

Humans

Humans 10 Inventors Who Died Awful Deaths in Their Own Creations

Animals

Animals 10 Ways Animals Use Deception to Survive

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Misdirections Directors Used to Manipulate Actors

Politics

Politics The 10 Boldest Coup Attempts of the 21st Century

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Things That Would Have Killed You in the Old West

Books

Books 10 Pen Names More Famous Than Their Authors

10 War Crimes of the US Civil War

When we think of war crimes, we think of the Nazis and Stalin’s henchmen. The American Civil War has been covered many times on Listverse, but history classes tend to overlook the presence of genuine crimes against the understood rules of proper war-time conduct. Here are 10 of the most heinous examples.

10

Silas Gordon’s pro-slavery, anti-Union activities resulted in the Union burning down every town and farm in Platte County, Missouri twice. He appears to have been consumed by an intemperate fury against the North, and more than once killed people on mere suspicion, without any evidence of wrongdoing. He was probably responsible for the Platte Bridge Tragedy, in which a rail trestle was burned through, collapsing under the weight of a passenger train, killing at least 17 men, women, and children.

In retaliation for his guerrilla tactics, Colonel James Morgan burned down platte City and apprehended three of Gordon’s men, William Kuykendall, Black Triplett, and Gabriel Chase. They pled for a legitimate trial before a judge, but Morgan had them taken to Bee Creek Bridge, where Triplett was shot by 8 men with muskets. Chase fled with arms bound behind him, but sank to his waist in the muddy bank, where a soldier caught and bayoneted him through the throat with such force that he nearly decapitated him. Kuykendall had played dumb through all of this and his ruse worked. He was spared.

9

Ferguson was a Confederate guerrilla possessed of the same raging hatred of the Union as Silas Gordon, and led various posses of armed Confederate sympathizers, and sometimes soldiers, in ambushes and murderous raids throughout middle and eastern Tennessee. He is notorious for acting with marked cruelty and targeting anyone, even women and children, whom he felt crossed him or supported the North.

He is said to have cut the heads off 80-year-old men and rolled them down hills into towns. He was arrested within 3 months of returning home to Nashville after hearing news of Lincoln’s assassination, and was tried and hanged on 20 October 1865 for 53 counts of murder. He had personally knifed and shot unarmed civilians for their support of the abolitionist cause. His actions after the First Battle of Saltville, Virginia were specifically cited, in which he and his men invaded a Union field hospital and shot and stabbed to death over two dozen soldiers of the 5th U. S. Colored Cavalry regiment, including white officers.

8

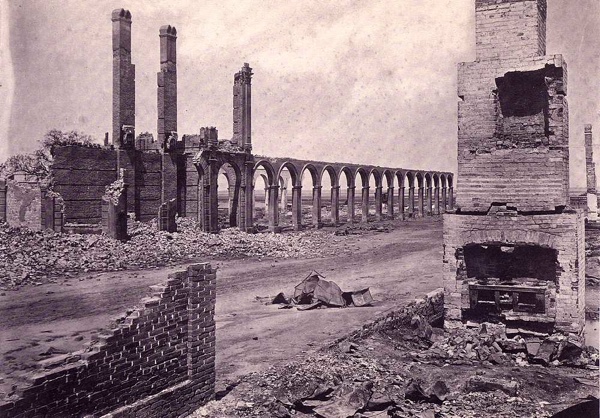

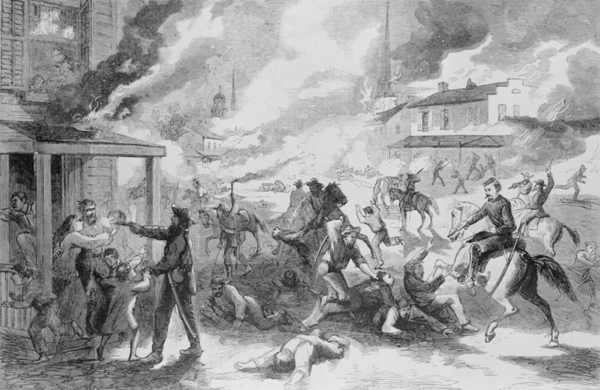

This campaign is more popularly known as Sherman’s March to the Sea. It is dated from 15 November, in the aftermath of General John Bell Hood’s accidental razing of much of Atlanta, Georgia, to 21 December 1864. Hood’s intent was to burn military supplies lest they fall into General William Sherman’s hands, but most of the city was made of wood and the winds were high.

Sherman ordered his army of 62,000 men with 64 cannons to march from Atlanta 300 miles southeast to Savannah, Georgia and destroy absolutely everything in their path, especially the railroads. They ripped apart the ties, heated and wrapped the rails around trees, dynamited factories, and burned down towns, farms, banks and courthouses. Sherman had given orders that the civilian population was not to be harmed personally unless they resisted, and that his intent was to break the South’s back, physically and psychologically, and put an end to its stubbornness.

Whether the march itself constitutes a war crime is still a fiercely contended subject. It is effectively the same form of warfare as dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was understood in both cases that the civilians, not just the military, would suffer terribly, and civilian outcry would help put an end to the war. But Sherman had no intention of deliberately killing civilians and the march must be left open to debate because of this.

Nevertheless, Sherman knew that civilian deaths would be unavoidable and explained himself in a speech after the war with the statement, “War is Hell.” Uncorroborated reports exist of a massacre of 200 civilians north of Columbia, South Carolina a few months before the march commenced, so Sherman knew full well what his men would do whenever no responsible eyes watched them. Three days after Atlanta was fully evacuated, Sherman ordered the city’s unburned sections shelled to ruins. One shell passed down through a house and blew off the legs of a man named Warner. The same shell cut his daughter in half.

7

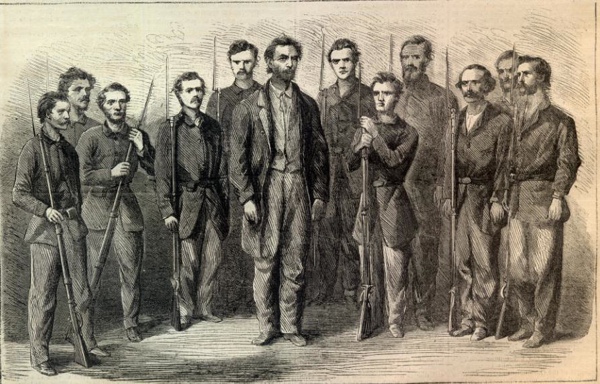

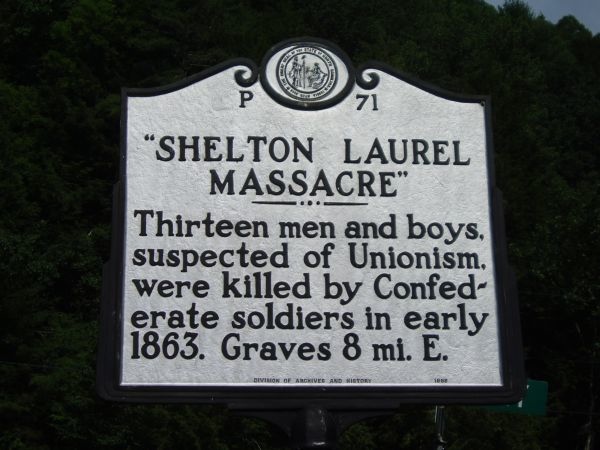

In January of 1863, at the height of the war, Lieutenant Colonel James Keith was dispatched with the 64th North Carolina Regiment to the town of Marshall, in Madison County, on the border with Tennessee. A posse of pro-Union civilians had broken into the home of Colonel Lawrence Allen, looted and destroyed much of it, then broke into a storehouse for salt and stolen what they could carry, then blew it up with gunpowder kegs.

Keith was enraged and, with the 64th, he searched the Shelton Laurel Valley, found and fought with them, shot down 12, and captured about 7. He then tracked down these men’s family homes and tortured their mothers, sisters, wives, and daughters by breaking their fingers until they revealed the locations of about 8 more Union sympathizers. Keith arrested these men and marched the 15 of them for Tennessee, but two escaped into a steep ravine.

Keith deliberately disobeyed the order of the North Carolina Governor, Zebulon Vance, to hold the prisoners until they could be tried, and had them all executed by firing squad and thrown in a ditch. Keith was given 2 years in prison for this before escaping. He was never seen again.

6

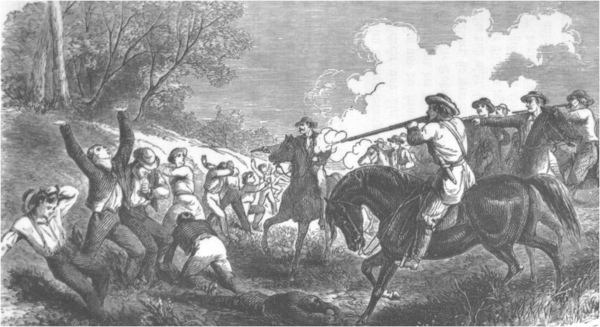

Few places throughout the United States saw quite the anarchic bloodshed as the Kansas Territory. Senator James Lane led a raid on Osceola on 23 September 1863, in pursuit of General Sterling Price’s invading army, east of Harrisonville and Clinton, Missouri, near the present border with Kansas. Lane was a staunch abolitionist, Price just as staunchly pro-slavery. Lane had about 1,100 men at his disposal and skirmished with a much smaller Union detachment outside Osceola. When the Union soldiers were routed, they fled into the surrounding woods and cornfields, and Lane led his men into the town where they burned 797 of 800 buildings to the ground.

They took care to kill none of the civilian population, but forced them from their homes and then searched every room of every building and stripped all belongings deemed of value, before torching everything, even the church. Lane stole a piano for himself. He then ordered 9 men of military age, one of them 16 years old and sobbing over his dead horse, to be tried on suspicion of aiding the Confederacy, and had them shot dead.

5

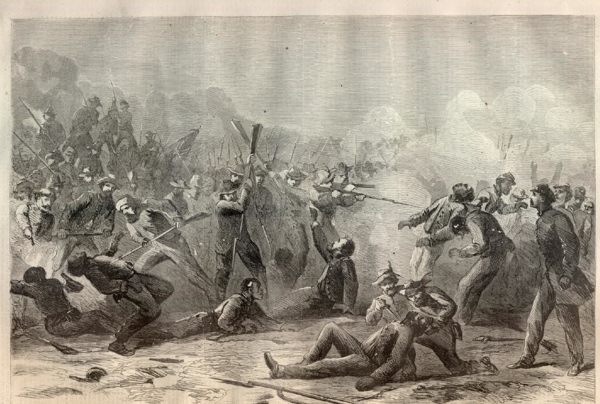

At about 9:00 in the morning, on 27 September 1864, William “Bloody Bill” Anderson and a force of 80 guerrillas, including Jesse James, rode into Centralia, Missouri to rip up the North Nissouri Railroad. Anderson decided against this and instead, they stopped an arriving train and looted it and its 125 passengers, of whom 23 were Union soldiers. Anderson ordered the train evacuated, the 23 soldiers lined up and stripped, and then asked which of them were officers. Only one man stepped forth, but instead of killing him Anderson’s men shot down the other 22, then scalped, skinned, and dismembered them.

This officer, Sergeant Thomas Goodman, escaped around noon. Some three hours later, 155 Union mounted infantry armed with single-shot muzzle-loading muskets arrived in town, heard of Anderson’s action, and attacked him from the rear. Anderson’s men were armed with up to 4 revolvers each, most stolen over the years, and routed the infantry within 3 minutes of engaging them. Anderson survived to be killed in a battle in October of that year.

4

Fort Pillow was a Union stronghold on the Tennessee banks of the Mississippi River, near Henning, and on 12 April 1864, it was besieged by up to 2,500 cavalrymen under General Nathan Bedford Forrest, who would later become the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. Forrest easily took control of the high ground around the fort and demanded it be surrendered. The commander refused and Forrest’s men assaulted and overwhelmed the defenders. Many of them were shot down as they fled into the river.

Both sides of the war reported that after the fort’s surviving garrison, most of it comprised of black soldiers and civilian workers, surrendered and was disarmed, the Confederates swarmed upon them and bayoneted, knifed, and clubbed some 250 men to death in an orgy of sadism. Over two dozen were castrated and lynched. Forrest always maintained that this massacre was a fair fight because the defenders were armed to the very end.

3

In retaliation for #6, Captain William Clarke Quantrill led a raid into Lawrence, Kansas on 21 August 1863. Lawrence was a hotbed of anti-slavery sentiment and Quantrill was a fervent pro-slavery Confederate guerrilla, who had effectively enlisted into the Army under General Sterling Price, but deserted to form his own band of soldiers. There was little law in the Kansas Territory, and Quantrill’s Raiders are known for more than one infraction of it.

Quantrill was especially out to kill James Lane, but Lane escaped into a cornfield. The Raiders descended from Mount Oread into town at about 5:00 in the morning and burned down every business and municipal building. Homes were spared torching but the families were driven outside and the husbands, fathers, and son all shot dead on their porches, in the streets, even in their beds. The women were raped, some of them and some children shot down or trampled while they fled. At least 185 men and boys as young as 11 were executed merely for being able-bodied.

2

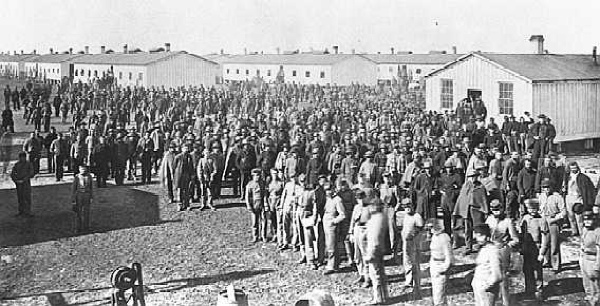

Douglas was the Northern counterpart to the next entry, a prison-of-war camp in Chicago, Illinois for Confederate soldiers. It was built as a training depot for Union recruits, but by March 1862 was refitted as a prison for the large numbers of captured Rebels. It operated in this capacity until the end of the war. Within the first month its use as a prison resulted in the death of 1 in 8 inmates from exposure to the harsh winter or pneumonia. The prisoners were poorly cared for in the way of medicine and proper diet. They received enough to eat to save them from starvation, but did not receive much fruit or onions, which allowed disease to suppress their immune systems.

By the war’s end, the Camp had gone through no less than 15 commands of 12 different wardens, none of whom was able to run the facility efficiently. Not only were the prisoners grossly neglected, they were not even properly supervised, and there were over 100 successful escapes. From June 1864 to the end of the war, inmates caught breaking any rule were tortured on the wooden horse, a sharply edged, wood pyramidal beam that rested between the buttocks against the tailbone. Prisoners were forced to sit on it with weights tied to their ankles for hours, even in snow or rain, until they passed out and fell off.

From 1864 on, the inmates were no longer fed adequately, but given only enough to keep them alive and hungry, purely for the guards’ amusement. They were forced to stand at attention in freezing rain and sleet for hours, during which time the guards robbed them of any valuables.

The death toll by the war’s end has been put at 4,454, but many went unreported, and the total figure may be as high as 6,000, most from exposure and disease brought on by malnutrition. This is at least 17% of the 26,000 prisoners sent to Douglas.

1

Camp Sumter was a Confederate Prisoner-of-War Camp for Union soldiers, today a historic site located in Andersonville, Georgia, from which the prison derives its more well known name. Its conditions were little known from its opening in February 1864 until it was liberated in May 1865, one month after Lincoln was assassinated. When the mistreatment of prisoners came to light, the entire nation and even Europe were disgusted and dumbfounded by the photographs of horrifically emaciated prisoners who somehow found the strength to survive.

The prison covered 25 and a half acres east of Andersonville, and was nothing but a bare patch of land surrounded by woods and fenced in twice. The outer fence was a log palisade 1,620 feet by 779 feet, with two entrances in the west wall leading into town. 19 feet in from this palisade stood an inner fence of chest-high posts topped with single crossbeams. This was nicknamed the dead line. Anyone who tried to cross it for the outer palisade, or even touched it, was shot without warning.

Inside the camp, there were only eight small buildings that could house a total of about 100 men. The prison held 45,000 by the end of the war. Most were given tents in which to sit or sleep, but the Georgia summer was overwhelming. 13,000 of those men died within 7 months of summer incarceration from sunstroke, starvation, or disease. The entire prison population suffered from a hookworm epidemic, causing most of them to defecate bloody diarrhea filled with worms.

The prison was very poorly supplied with food and medical provisions, and when Dr. Joseph Jones was assigned to investigate, he vomited twice during the one hour he toured the camp, and contracted a severe case of the flu which he warded off with oranges. He then asked the commandant, Henry Wirz, why Wirz was not suffering from scurvy, which was rampant throughout the camp. Wirz replied that he ate apples and oranges. “And the prisoners?” Jones asked. Wirz shrugged and said, “What about them?” Prisoners were able to pull out their own teeth with their fingers because of vitamin C deficiency. 3,000 died per month, or 100 per day.

They had no clean drinking water, but were forced to drink from the same creek running through the camp’s center in which they bathed and which caught about half of all liquid and solid waste. Wirz was tried, court-martialed, and hanged for murder on 10 November 1865, the only Confederate officer to be so executed. His primary defense in court was that the prison’s food and water never arrived by train. When he was hanged, his neck did not break, and he strangled to death for 9 minutes.