Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Our World

Our World 10 Science Facts That Will Change How You Look at the World

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

10 Historical Cross-Dressers

Sexual dimorphism—the physical difference between males and females—exists in most species to various extents. Most human cultures emphasize this contrast by dressing the sexes in different ways. But for a variety of reasons, some people have felt the need to adopt the clothes of the other sex. Today this is far more tolerated than at any other time during history; In the past, cross-dressers have risked social opprobrium and even legal punishment.

As all of the following people lived before the (at least partial) recognition that some people are transgender, we do not have enough information to say with certainty which gender they truly identified with—so there may be some pronoun jumbling involved. Here are ten historical cross-dressers:

There was little room for romance in the brutal lives of pirates in the eighteenth century, despite the plethora of fictitious narratives told about them. It was a hard life among hard men. And yet, several women managed to make their living as pirates.

Mary Read—anatomically a female—had her first experience of being treated as a boy when her mother dressed her as one so that the family would receive support from elderly relations. She continued to dress as a man throughout her life, and worked as a footman and ship’s mate. She then served in the military as a foot soldier, until she fell in love with another soldier and eventually married him. When her husband died, she took to wearing men’s clothing again.

In an age when even having women on a ship was thought to be unlucky, Mary Read became an active member of a pirate crew. This happened when the ship she was sailing on was captured by the band of pirates, who asked her to join them.

When the pirate vessel was itself captured, Read was put on trial and sentenced to death by hanging. She claimed to be pregnant—a delaying tactic known as “Pleading the belly”—and the execution was postponed until she might give birth. But Read ended up dying in prison, thanks to an illness.

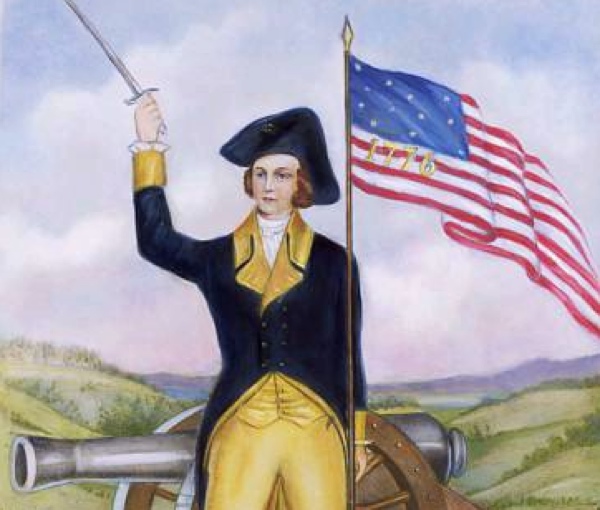

During the American War of Independence, a soldier by the name of Robert Shurtliff Sampson became ill with a fever. The army doctor sent to treat him was startled to discover that the man he was tending was actually a woman.

Deborah Sampson wished to fight but—being a woman—found herself unable to enlist. So she took up the identity of her dead brother, disguising herself in order to join the revolutionary army. She fought in several battles and was gravely wounded in the leg by two musket balls. Afraid lest her sex be discovered, she asked her comrades to leave her to die—but in spite of her protests, they took her to a doctor. She allowed him to treat a head wound, but insisted that her leg be left untouched. Deborah later removed one of the balls herself with a knife.

Another doctor later discovered her secret after she fell ill, but he kept her secret until the war was over. But when it then became known to her commanding officers, she received a dishonorable discharge. Eventually, however, after a marriage and children, she was given a pension by the new government—a first for a female soldier.

Joan of Arc is a Catholic saint and a French hero of the Hundred Years’ War. We know much about Joan during her years of service, but very little of her previous life. Indeed, at her trial, even Joan had to guess that her age was nineteen. But from what we can gather, it seems that the young Joan began having delusions—or receiving messages from God—at about the age of twelve. As a result of these divine communications, she believed that she had been chosen to force the English out of France.

After being granted a meeting with an army commander, she predicted a victory for the French—a prediction which came true. This gave her the credibility she needed to gain a meeting with King Charles VII. It was on the way to this meeting that she first put on male clothing. At her trial, she claimed that she wore male clothing so as to prevent rape. She was sent by the king to join the army, and began to borrow armor and other equipment, giving her the same appearance as the male knights. Though she did not participate actively in any battles, she did play a strategic role in several victories.

Joan was eventually captured and traded to the English, who put her on trial for heresy and for dressing as a man. It was her now-habitual male dress which led to her death. After escaping with her life from an initial trial, she had signed an agreement to never dress as a man again—yet within four days resumed this habit. This was viewed as a relapse of heresy, and she was burned at the stake.

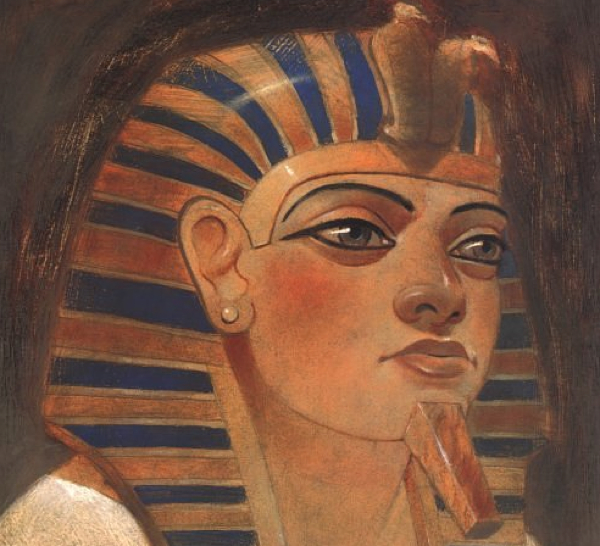

In the ancient world, masculinity was often viewed as an indispensable quality of leaders. Even today that often remains the case: Margaret Thatcher, for example, was taught to speak in a lower voice in order to sound less feminine. It should come as no surprise, then, that female rulers in the past sometimes took on male garb to reinforce their rule.

Hatshepsut was the daughter of a Pharaoh. She appears to have acted as a regent for her son, the young Thutmosis III, in the sixteenth century BC, but also to have ruled in her own right as Pharaoh. Her rule was fairly long and prosperous for Egypt, and she inaugurated trade missions and building schemes.

Statues of Hatshepsut show her in the regalia of the Pharaoh—including the traditional false beard. On the other hand, there are also statues which show her in more feminine attire. It seems that Hatshepsut was content to play the role of King when it came to official matters, but continued to dress a woman in her daily life.

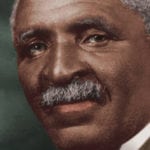

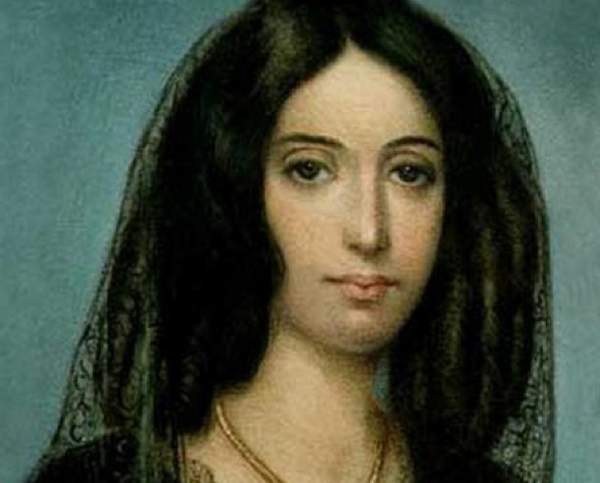

George Sand was the pseudonym of the French writer Amantine Dupin. It was not uncommon for female writers to take on male pseudonyms around this time—but not many of them followed through so completely by dressing as a man.

George Sand was the pseudonym of the French writer Amantine Dupin. It was not uncommon for female writers to take on male pseudonyms around this time—but not many of them followed through so completely by dressing as a man.

George Sand led a scandalous life, even by the standards of nineteenth century France. She conducted affairs with several men—famously including Frederic Chopin—and smoked cigars in public. But it was her decision to wear male clothes which caused the greatest damage to her reputation. As a writer, Sand enjoyed the freedom given to her whenever she successfully masqueraded as a man; cross-dressing unlocked new places to go. She also had a practical excuse: men’s clothes did not wear out as quickly as women’s, and they were apparently far more comfortable.

We have already heard of women dressing as men to serve in battle—but none with such panache as Hannah Snell. In 1750, a soldier announced to his colleagues while drinking: “Why gentlemen, James Grey will cast off his skin like a snake and become a new creature. In a word, gentlemen, I am as much a woman as my mother ever was and my real name is Hannah Snell.”

This announcement came after Snell had served two years with her regiment in India. She received wounds in battle but managed to conceal her sex, possibly by treating herself. After she returned to England she reveled in the publicity caused by her service as a female, and told her story to a publisher. She soon married, and opened a pub called “The Female Warrior.”

Edward Hyde, 3rd Earl of Clarendon, was British Governor of New Jersey and New York from 1701 to 1708. Not naturally suited to such a position, he was regarded with contempt by the natives.

It is his enemies who tell the stories of the Earl’s cross-dressing, so we must take them with a pinch of salt. It was said that several times a week, the Earl would get very drunk and roam the streets in his wife’s clothes. It was also claimed that he once appeared at an official event in a gown. When he saw the shock of those around him, he tried to explain: “You are all very stupid people not see the propriety of it all. In this place and occasion I represent a woman [Queen Anne], and in all respects I ought to represent her as faithfully as I can.”

While we cannot be absolutely certain of the claims against Hyde, we do know that complaints were lodged against him with the Crown, and that he was eventually removed from his post. He died in poverty, and was buried nonetheless in Westminster Abbey.

Catalina de Erauso was a seventeenth century Spanish woman who became known as “The Nun Ensign” for her campaigns as a soldier. Her story is told in her autobiography, though there are doubts about the truth of some portions. It is beyond doubt, however, that Erauso dressed as a man and fought with the Spanish army in Chile and Peru. Apparently she served as a common soldier under the leadership of her own brother, who failed to recognize her.

After being injured in a duel, and fearing death, she confessed her sex. After recovering, she confessed again—this time to a bishop who revealed her identity to the world, spreading her fame in the process. When Erauso returned to Spain, she claimed a pension from the king and received the right to wear male clothes from the Pope. She eventually returned to South America, and lived the rest of her life by the name of Antonio de Erauso.

Lady Eleanor Butler and the Hon. Sarah Ponsonby were two of the most celebrated eccentrics of the Georgian era. Born in Dublin in the nineteenth century, they grew up two miles from each other and became firm friends. When Eleanor began to seem too old for marriage, she was pressured to enter a convent by her family. Sarah, in a similarly desperate situation, faced an unwanted marriage. In 1778, the two ladies ran away from their families. When they were finally tracked down, they were found to have dressed themselves as men in an attempt to throw their relatives off.

The first attempt at escape had failed—but the two could not be dissuaded. They moved to a manor outside Llangollen in Wales, and proceeded to live exactly as they pleased. They cut their hair short like a man’s, and could be seen wearing top hats. Though they lived mostly private lives, they still managed to entertain some of the great figures of the age, such as Byron, Wordsworth, and Scott. Queen Charlotte was so charmed by them that she granted them a pension.

Both ladies died within two years of each other after spending more than fifty years together.

Chevalier d’Eon spent the first fifty years of his life as a man called Charles, and the final decades as a woman called Charlotte. Before the word transvestism was coined, cross-dressing was called Eonism in his honor.

Chevalier d’Eon spent the first fifty years of his life as a man called Charles, and the final decades as a woman called Charlotte. Before the word transvestism was coined, cross-dressing was called Eonism in his honor.

A soldier, diplomat, and spy, the chevalier was sent as a very young man to the court of the Empress Elizabeth of Russia. Because of strained relations between France and Russia, he was disguised as a maid, and secretly delivered a message from Louis XV. He later served the French ambassador in London, but proved unpopular with his boss. While he was in London, rumors concerning the true gender of the Chevalier led to heavy bets being placed. But when he refused to be examined, the bet was cancelled.

d’Eon began dressing and living as a woman after being forbidden to return to France. He claimed that he was actually a woman. The French government refused to pay this woman’s pension unless she dressed appropriately; and so the Chevalier became Mademoiselle d’Eon.

Her final years were spent living in poverty after her pension was cancelled during the French Revolution. She shared a small apartment with another lady. When d’Eon died in 1810, the doctors who examined her found that she was indeed anatomically male.