Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Wars Fought In The USA

Battles, rebellions, skirmishes, disputes, and tiffs have occurred in America right up to the 20th century. Here are 10 historic conflicts that took place within the land borders of the United States of America and didn’t happen during the Revolutionary or Civil Wars. For the purposes of this list, we’ve also excluded the American-Indian Wars.

The Lone Star State suffered a few growing pains in its earlier days, not helped by the near constant threat of invasion from neighboring Mexico. In 1842, the capital of the Republic of Texas was Austin. After receiving a demand for surrender from a Mexican general backed by an army, Texas president Sam Houston and the state Congress decided Austin might be in danger and ordered the seat of government—and its accompanying archive of official public documents and records—moved to the city of Houston.

The citizens of Austin weren’t pleased. Fearing the president’s namesake city would become the new state capital, they formed a vigilante committee and swore armed resistance. The first attempt failed when the man appointed by the president to accompany the archive on its move was refused horses and wagons by the angry residents. The second attempt ended in humiliation when contemptuous citizens flouted the president’s authority, shaved the manes and tails of his messengers’ horses, and refused to let the men carry out their duty. At the end of 1842, a frustrated President Houston was forced to send a company of thirty Texas Rangers, with orders not to provoke bloodshed, to take the government archive from Austin.

The Rangers entered the town on the morning of December 29th and began quietly loading the archive into wagons, unnoticed by the citizens—except one. Upon witnessing the soldiers’ activities, Angelina Belle Peyton Eberly, who ran the local boarding house, hurried to a six-pound cannon kept loaded with grape shot in case of Indian attack, and set off the charge (fortunately, no one was injured). By the time the vigilante committee members assembled, the Rangers raced out of town, taking the precious archive with them.

Undaunted, the leader of the vigilantes, Captain Mark Lewis, commandeered a cannon from the nearby arsenal and took off after the Rangers with a couple of dozen furious citizens right behind him. They caught up to the company of Rangers the next day at Kenny Fort and at cannon-point, forced them to hand over the archive, which was returned to Austin.

At that point, President Sam Houston gave up, the government archive remained in Austin, and the Archive War ended with only a few shots fired and no one hurt.

Not to be confused with the Red River War in 1874 (U.S. Army vs. Southern Plains Indians). The Red River Bridge War in 1931 began with, unsurprisingly, a bridge spanning the Red River between Denison, Texas and Durant, Oklahoma.

This was a free bridge built jointly by Texas and Oklahoma, much to the annoyance of a nearby older toll bridge also spanning the Red River, now made redundant. In July 1931, the toll bridge company filed for and received a court ordered injunction against the Texas Highway Commission, citing an alleged, unfulfilled agreement to purchase the toll bridge and pay out the company’s contract. The injunction prevented the bridge’s opening. Governor Sterling ordered barricades erected on the Texas side.

However, neither the injunction nor telegrams from Sterling prevented Oklahoma Governor Murray from issuing an executive order to open the new free bridge by asserting his state’s claim to ownership of the land on both sides of the river. He sent workers to destroy the Texas barricades, causing Sterling to respond by sending a couple of Texas Rangers to rebuild the barricades. The situation continued to escalate when Murray ordered crews to block the Oklahoma side of the toll bridge, and traffic flow across the Red River came to a halt. Finally, the Texas legislature granted the toll bridge company the right to sue the state, the injunction was withdrawn, and the free bridge opened. But that isn’t the end of the story.

The toll bridge company went to federal court to prevent Murray from continuing to block their bridge. The Oklahoma governor’s response? Declare martial law and post a National Guard Unit at the sites of both bridges on both sides, prompting Texans to fear an invasion. Murray led guardsmen across the toll bridge while brandishing an antique revolver, and ordered the toll booth torn down and burned. The two Texas Rangers inside fled.

In August, the guardsmen were withdrawn and the Red River Bridge War ended.

A dispute took place over a piece of land called the “Toledo Strip”—where the city of Toledo, Ohio would later be located—which in 1835, gave U.S. President Andrew Jackson a headache by touching off the border skirmish called the Toledo War.

The situation was a tad complicated and boils down to: the original surveyors of the land in question made a mistake and assigned it to Ohio when that state’s border was created. In 1835, another survey corrected the error and set the land within the border of Michigan (not yet a state but a territory). However, this property became hotly contested because of its location at the mouth of the Maumee River. Canals were planned to connect to the Mississippi River, then a vital commercial artery. A city in that location had great potential for wealth.

Hating the prospect of losing a future major trade center, the Ohio legislature called for another survey. This time, the borders were adjusted to no one’s satisfaction.

Matters boiled up again when Michigan applied to the US government to become a state. Ohio Congressmen managed to block the application and wouldn’t budge unless Michigan agreed to revert back to the old boundary line and give up the Toledo Strip. Adding insult to injury, Ohio governor Lucas refused to negotiate, created a county from the disputed land (named after himself), and appointed a judge and sheriff. Michigan governor Stevens promptly mobilized troops and marched to Ohio.

During the brief Toledo War, both states were involved more in bluffing and posturing than actual fighting. The Michigan militia arrested a few Ohio surveyors and officials they caught on the border. They also passed a slightly larger military budget than Ohio in a blatant “mine’s bigger than yours” display. Ohio sent militia to guard their interests, though the only casualty was a Michigan sheriff stabbed to death by an Ohio man in a bar brawl, and the only shots fired were over the heads of the “enemy.”

In 1836, President Jackson ended the Toledo War by proposing to give the Toledo Strip to Ohio and assign a nice chunk of resource rich land to Michigan in compensation. If Michigan rejected the compromise, he would refuse to sign the bill giving the territory its coveted statehood. Needless to say, Michigan took the deal.

In 1841 in the smallest U.S. state, Rhode Island, one man and his supporters instituted insurrection against what they considered unfair voting practices and the disenfranchisement of many of the states’ residents. Their cause became known as the Dorr Rebellion.

Immigration caused an increase in Rhode Island’s population as well as a workforce for the burgeoning Industrial Revolution. Due to the original charter, only property owners had the right to vote, and at the time, more than half the state’s male residents didn’t qualify. Previous attempts to change the qualification through official government channels failed. Finally in 1841, Thomas Dorr and like-minded citizens decided if state legislators couldn’t be bothered, they’d hold a People’s Convention and effect change themselves.

The Dorrites drafted and ratified a People’s Constitution which reformed the voting qualifications, giving all white male residents the franchise. They also “elected” Dorr as governor. Dorr and his supporters were opposed by state legislators including the officially elected Governor King, who used intimidation and force against the popular rebellion.

Backed by many militia members, Dorr attempted to lead an attack on the arsenal in Provincetown in 1842, but the attack failed. He and his followers retreated to regroup, only to find their retreat cut off by government forces. The rebellion fell apart and Dorr fled the state. On his later return to Rhode Island, he was arrested, convicted, and sentenced to life in solitary confinement at hard labor, but he was pardoned and released in 1845.

The Rhode Island legislature did eventually reform the state Constitution, giving the vote to white male residents who owned property or could pay a $1 poll tax.

As a consequence of the Yazoo Land Fraud Scandal of 1795, in 1802 Congress passed a rather vaguely worded law granting certain tracts of land to Georgia which appeared to include the “Orphan Strip”—a small, isolated, and unwanted region surrounded by North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. Nobody wanted to govern the wilderness, yet this troublesome bit of real estate would spark a conflict ending in tragedy.

The area had a checkered history. First inhabited by the Cherokee, the Orphan Strip was claimed by South Carolina, who later ceded it to the US government, who in turn passed it back to the Cherokee. The Cherokee still didn’t want it, so tribal leaders handed it over to Washington D.C. a second time. The Orphan Strip became public domain. Despite its isolation and popularity with outlaws and fugitives, some settlers from North and South Carolina decided to make the region their home.

The trouble began in 1803, when Georgia annexed the Orphan Strip and named it Walton County. The state of North Carolina didn’t care, but the 800 some-odd settlers did. Their land grants had been issued by North Carolina and in some cases, South Carolina, so they refused to pay taxes to Georgia in 1804. Walton County tax officials responded by ramping up the pressure with intimidation and attempts to dispossess. Tensions peaked when a Georgian official, Sam McAdams, killed North Carolina constable, John Hafner.

Governor Turner of North Carolina sent his state’s militia marching into Walton County to arrest the men responsible for Hafner’s murder. Ten Walton officials were captured and sent to North Carolina for trial. They escaped jail and went on the lam.

Disputes between North Carolina and Georgia over the land continued. Finally in 1811, a new survey put Walton County within North Carolina’s border, and Georgia accepted the findings … until 1971, when a state commission reported Georgia still had a legal claim to the region. The governor of North Carolina called out the militia to defend the border. Fortunately, both sides kept their heads this time and the matter was resolved peacefully.

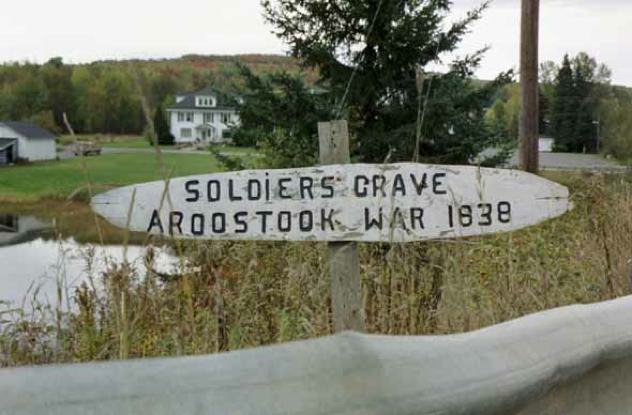

Also known as the “Lumberjack War” or the “Pork and Beans War,” the Aroostook War was a border dispute between Maine and Canada (and the US and Great Britain) in 1838. While no one died, the conflict did mange to achieve its own theme song.

At the time of the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War, the border between what would become Maine and New Brunswick, Canada (British territory) was vaguely set at the St. John’s River. Since the region on both sides of the boundary line was covered in timber, Acadian loggers and trappers quickly settled there, ignoring the border. When Maine applied for statehood in 1820, legislators were surprised to find French-Canadian settlers on their side of the river. They gave land grants in the nearby Aroostook River valley to Americans, who soon began disputing with their Acadian neighbors.

King William I of the Netherlands was asked to arbitrate, but Maine rejected his compromise in 1831. The conflict heated up in 1837 when officials from Maine and New Brunswick began making arrests for trespassing in the Aroostook area. Canada accused Maine of timber theft and feared an invasion. The arrival of British forces from Quebec triggered Maine legislators to send a force of 200 militiamen to oppose them.

The US Congress dispatched 10,000 volunteer troops to enforce peace while negotiations with Britain’s representative went on—and if hostilities broke out, to defend the border by force. To everyone’s relief, no fighting occurred and no one was killed—though folklore speaks of a Canadian pig or possibly a wandering cow shot by mistake.

In March 1839, a settlement was finally reached, though a final decision on the border between Maine and Canada wouldn’t be achieved until 1842.

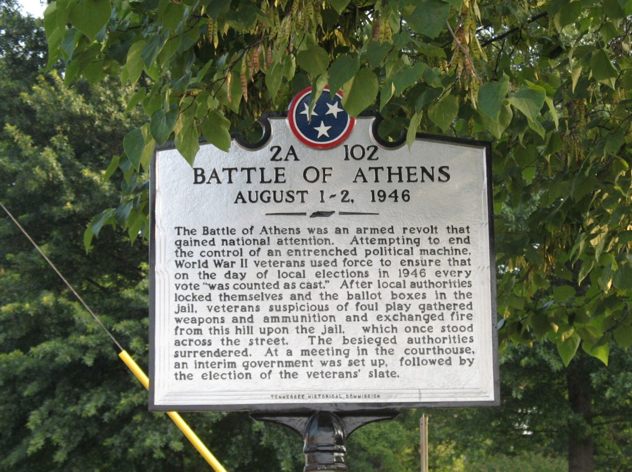

Following World War II in 1946, violence erupted when returning American soldiers discovered their Tennessee county had been taken over by political corruption. Their plan to take it back involved bullets—lots of bullets—and dynamite.

Why Athens in McMinn County, Tennessee became a battleground was due to Paul Cantrell, a Democrat running for sheriff in the 1936 election. He won over his Republican opponent, although the victory was tainted by rumors of fraud. Cantrell was a corrupt sheriff—for example, since state law allowed his office to collect fees for each person booked, jailed, and released, deputies boarded buses passing through the city and arrested passengers on bogus charges of drunkenness, forcing them to pay fines. Prostitution, gambling, and kickbacks from illegal drinking establishments were commonplace.

The tide began to turn in 1945 when GIs returning to Athens were subjected to arrest on the flimsiest excuses and heavily fined. When the fed up soldiers attempted to support their choice for sheriff against Pat Mansfield (by then, Cantrell had been elected to the state Senate and backed Mansfield’s bid), matters boiled over into direct conflict on Election Day 1946.

Mansfield hired several hundred armed “deputies” to patrol the voting precincts in Athens—and no doubt to assist in the typical ballot stuffing and voter intimidation. The volatile situation escalated when Walter Ellis, an ex-GI and volunteer poll watcher, was arrested by Mansfield’s deputies and held without charge. A black resident, Tom Gillespie, was refused the right to vote, beaten, and shot. More GIs were arrested and threatened with violence. By the end of the day, the former soldiers had enough.

They broke into the town armory for weapons and besieged the jail, where Mansfield and his deputies had taken the ballet boxes. Battle continued sporadically throughout the night, resulting in wounded on both sides. When the GIs ran out of bullets around dawn, they began throwing dynamite. The deputies inside the jail surrendered.

The highly publicized Battle of Athens not only ousted corruption from one county in Tennessee, the lesson learned would ultimately lead to great reforms in Southern politics.

A border dispute in 1839 between Missouri and Iowa culminated in the Honey War—a bloodless if slightly rowdy conflict whose mark can still be seen in the landscape today.

The border between Iowa and Missouri had originally been drawn in 1816 by J.C. Sullivan, a surveyor, creating the “Sullivan Line.” However, less than a decade later, the exact whereabouts of the boundary line were in question. The matter didn’t cause trouble until 1838, when Missouri legislators ordered a new survey done. The result, adopted by the Missouri government, shifted the border north into Iowa.

Settlers in the annexed area considered themselves Iowans, so were understandably disconcerted when Missouri officials attempted to collect taxes from them. Their refusal caused several valuable bee trees—a source of honey—to be cut down and taken as partial payment, a definite crime in the citizen’s eyes. Next time, the tax agents threatened, they’d come in force. Incensed Iowans chased them away and contacted Iowa Governor Lucas.

Expecting a fight, Missouri mustered a militia force of 600 men, who marched to the disputed area. Iowa lacked a militia, but eventually close to 1,200 volunteers armed with pitchforks showed up to defend their state’s honor … and were too late to do anything except stand around since the Missourians had already got tired of waiting and gone home. Missouri Governor Boggs and Governor Lucas quarreled over where the true border lay. In the end, the U.S. Marshals intervened to keep the peace.

At last in 1849-1850, the US Supreme Court decided to retain the old official Sullivan Line between Iowa and Missouri. Large, cast iron pillars were driven into the ground every ten miles to the Des Moines River to mark the boundary. A few survive today.

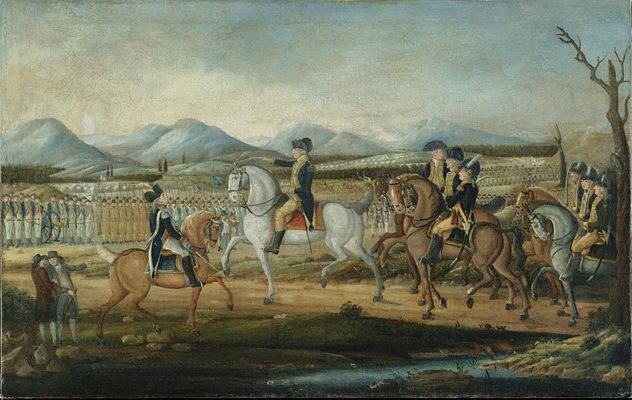

No one likes to pay taxes, and early Americans hated the idea with a passion. So when US Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton persuaded Congress to impose a tax on distilled spirits in 1791, he found himself with a rebellion on his hands.

The new federal government needed revenue, not only to run the country, but to pay off debts incurred during the Revolutionary War. Since a national income tax wasn’t yet in the cards, Hamilton felt it necessary to levy taxes on goods including a very unpopular “whiskey” tax which frontier farmers in western Pennsylvania felt was unfair. Many of these small scale farmers grew rye and corn. Distilling the grain into whiskey allowed indefinite storage and gave them a more reliable source of income than shipping the harvest east.

The farmers expressed their displeasure by refusing to pay the tax. While US President George Washington sought a peaceful solution and Hamilton urged military force, the farmers continued to ramp up the hostilities in the Whiskey Rebellion.

In 1794, a group of 400 rebels marched on Pittsburgh and burned the home of John Neville, a tax collection supervisor. Washington was left with no choice. Concerned the rebellion might spread to other states and end in the destruction of the federal government, he mustered a sizable militia. Under the command of Hamilton and Henry Lee, governor of Virginia, 13,000 troops marched into western Pennsylvania to put down the rebels.

When Hamilton and Lee’s militia reached Pittsburgh, the rebels fled and the Whiskey Rebellion ended. About 150 men suspected of being involved were arrested, but freed for lack of evidence. Two were tried, convicted of treason, and pardoned by Washington.

In 1802, President Thomas Jefferson, who had never agreed with the tax, repealed it.

In 1857-58, the so-called “Mormon problem” caused the conflict known as the Utah War or Buchanan’s Blunder, much to the eventual embarrassment of the US President.

The Church of Latter-Day Saints faced a great deal of persecution in the United States. Members were eventually forced to head west to establish a sanctuary in Utah. About 55,000 Mormons occupied the Salt Lake City, and Brigham Young acted as territorial governor. Against federal law, Young governed the territory as a theocracy, allowing church doctrine to take precedence over civil matters.

In the years since the Mormons had settled in the Great Salt Lake Valley, tensions between the church and the US government continued to rise over such issues as polygamy. Matters came to a head when hostilities against three federal judges by members of the church caused them to flee Utah, claiming they’d barely escaped with their lives (an exaggeration).

To deal with the problem, President James Buchanan appointed a new territorial governor and sent him to Utah accompanied by 2,500 U.S. Army troops. The commander of the expedition was given strict instructions not to attack citizens except in self defense. Unfortunately, no one thought to inform the Mormons.

In response to what they believed was an invasion, Utah mustered the militia and began collecting firearms, ammunition, and food stores. Citizen drills were established. A reconnaissance unit sent to infiltrate the US Army camp brought back renewed fears of mass hangings and abuse of Mormon women. The severely outmanned and under supplied Utah government declared martial law and prepared for the worst. Young told militia commanders to avoid bloodshed if possible.

In the meantime, the advance force of 1,250 US Army troops were harassed by the Utah militia and mounted scouts, who did not return fire even when shot at. Their orders were not to engage, but hinder and delay. Despite the reluctance to strike first, injuries and fatalities happened on both sides. Eventually, winter set in, bringing the “war” to a halt.

By spring 1858, Buchanan’s requests for further funding for the “Utah Expedition” were ignored by Congress. Mormon sympathies and the slavery debate made the action in Utah unimportant and unpopular. The Army was recalled. For the Mormons, life returned to normal. And while Buchanan’s Blunder had the unintended effect of generating sympathy for the Mormons, it also ended Young’s control over the Utah territory.