History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Interesting Facts About Temperature

Temperature is one of the fundamental measurements in physics, and it’s absolutely crucial to all kinds of life. But at ultra-high and ultra-low temperatures, things can get very weird—as you’ll see. Here’s a list of ten interesting facts about this important factor in our world:

The hottest man-made temperature ever recorded is 7.2 trillion degrees fahrenheit, or about four billion degrees celsius. Since we hope to minimize the use of superlatives in this list, let’s just say: that’s pretty hot. In fact, it’s about 250,000 times hotter than the temperature at the core of the sun. The extreme recording was made at the Brookhaven Natural Laboratory in New York, in their 2.4-mile-long Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider. Scientists had been smashing gold ions together, in an attempt to recreate big-bang like conditions by creating a quark-gluon plasma. In this plasma state, the particles that make up the nucleus of atoms—protons and neutrons—break apart, and create a “soup” of their constituent quarks.

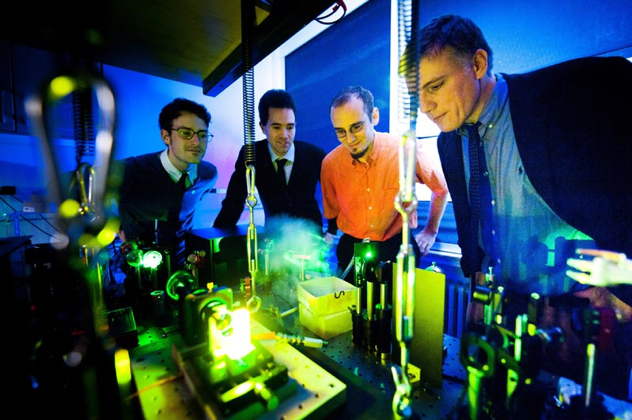

We’ve already made mention of the Bose-Einstein condensate. It’s a phenomenon that occurs to matter at a fraction of a degree above absolute zero. Though previously seen only at these super-cold temperatures, scientists were able to recreate the effect at room temperature, by using light instead of matter.

They managed to do this because of the relative density of the matter and the light; one of the scientists involved, Jan Klars, explained that “Our photon gas has a billion times higher density, and we can achieve the condensation already at room temperature.” They forced light to travel through two mirrors with particles of dye between them. As the light bounced back and forth, it lost a little bit of energy each time it passed through some dye. And when it reached room temperature, the light effectively began to behave like an ultra-cold gas made of traditional matter. This result takes on a whole new relevance when we learn that it could lead to new types of lasers—which, after all, should be the ultimate goal of all physics research.

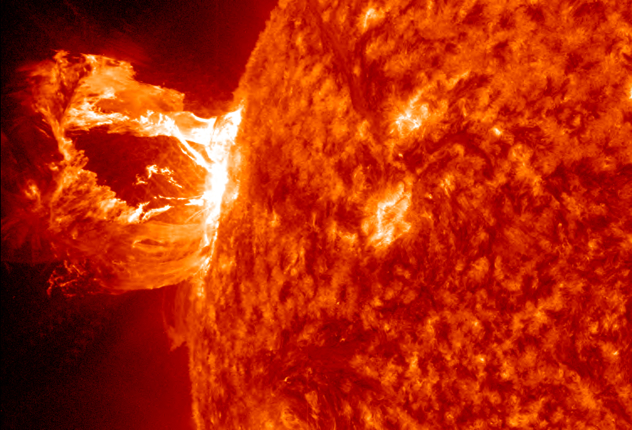

Some of you may be familiar already with the following comparisons—but take a moment to think about what they really mean, in relation to the normal temperatures of human experience. The sun—to borrow an understatement from an earlier entry—is pretty hot. It’s at its hottest in the centre, which reaches around twenty-seven million Fahrenheit (fifteen million Kelvin). In comparison, it’s actually less than ten thousand degrees Fahrenheit at its surface (about 5,700 K).

The centre of the Earth stands at about the same temperature as the surface of the sun. Apart from the sun’s centre, the hottest part of our solar system is the core of Jupiter, which, remarkably, is five times hotter than the Sun’s surface.

And the coldest-known place? That’s actually on our own moon, where temperatures in the shadows of some craters are only thirty Kelvin above absolute zero. The temperatures, measured by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, are even colder than those on Pluto.

The SI unit of temperature is the Kelvin. The temperatures used to define this are absolute zero—the bottom limit of temperature—and what known as the triple point of water. A triple point is defined as the temperature by which a substance’s traditional three states of matter exist in an equilibrium. At this point, the most infinitesimally small alteration to temperature or pressure can be used to alter its state one way or another.

To define one Kelvin, you take the difference in temperature between the triple point of water and absolute zero and divide it by 273.16. There are limited practical applications of the triple point of water, but its proximity to the melting point is key to causing the watery cushion needed to allow people to ice-skate.

The rules of nature that govern temperature are known as the Laws of Thermodynamics. Originally there was only a first, a second, and a third law—but then scientists came up with a fourth law. The newest law stated that “if two systems are each in thermal equilibrium with a third system, they are also in thermal equilibrium with each other.”

That basically means that if two objects don’t have a net exchange of heat with a third object, they’d not do so with each other—which is how we define them as being at the same temperature.

Scientists soon realized that this law is fundamental to the whole field of thermodynamics; they also realized that it should have been the first rule they formulated. Because “first law” was already taken, they gave it due respect by calling it the “zeroth law.”. It was around 1935 when the law was coined—meaning that scientists didn’t get around to formally defining what temperature meant until a couple of hundred years into the development of the field.

Some people have established their homes in the most unlikely of places. The coldest permanently inhabited places in the world are the towns of Oymyakon and Verkhoyansk in Siberia, which we’ve mentioned before. During winter, temperatures there average below minus fifty degrees Fahrenheit.

The coldest city in the world is also in Siberia. Yakutsk, with a population of 270,000, is not much warmer in the winter than its smaller cousins—often dropping below minus forty degrees Fahrenheit. But at the height of summer, temperatures can swing all the way up to the other end of the scale, to almost ninety degrees Fahrenheit.

The highest recorded average temperature belongs to the abandoned town of Dallol, in Ethiopia, which recorded an average temperature of ninety-six degrees in the 1960s. The record for hottest city is Bangkok, with average air temperatures breaking above ninety-three degrees between March and May.

But the record for hottest workplace likely goes to Mponeng gold mine, in South Africa. At two miles below the surface, rock temperatures can reach 150 degrees Fahrenheit. Ice must be pumped into the mine—and the walls insulated with concrete—to allow people to work there without perishing.

Making things cold has produced a lot of interesting and important results in science. Humans make the coldest known things in the universe, many orders of magnitude colder than anything that occurs naturally. Refrigeration allows temperatures of a few milliKelvin to be accomplished. The coldest temperature ever achieved is slightly below one hundred picoKelvins, or 0.0000000001 K. It’s necessary to use a type of magnetic cooling to achieve temperatures this low. Similar temperatures can be achieved on a small scale using lasers.

At these temperatures, matter behaves differently to the way it does normally (see Bose-Einstein condensate above as an example)—a fact which is key to revealing the many odd quirks of quantum mechanics.

If you were to take a thermometer out into deep space and leave it there, far from any source of radiation, it would read 2.73 Kelvin—a little lower than minus 454 degrees Fahrenheit. That happens to be the coldest naturally-occurring temperature in the universe.

Space is kept above absolute zero by background radiation left over from the Big Bang. Although space is nevertheless very cold, it’s interesting to note that one of the biggest problems encountered by astronauts is actually heat. Bare metal on orbiting objects can reach five hundred degrees Fahrenheit (260 C) due to the unimpeded heat of the sun, and needs to be covered in special coatings to lower the touch temperature to “only” 250 Fahrenheit (120 C).

Outer space itself, however, is constantly getting cooler. Theory has long predicted this, and recent measurements have confirmed that the universe is cooling by around one degree every three billion years.

It’ll continue heading towards absolute zero, though it will never quite reach it (an impossible feat). The background heat of the universe makes little difference to us; the effect of celestial bodies in our solar system and galaxy dwarf it. So it’s not going to counteract global warming, in case anyone has ideas.

Heat is a mechanical property of matter. Put simply: the hotter a thing is, the more energy its particles have as they move around. The atoms in a red-hot solid are vibrating more quickly than the atoms in a cold piece of material. Likewise, those in a liquid or gas whizz about with a speed which depends on how hot they are. That’s pretty basic stuff, which you probably learned in high school—but for hundreds of years until the late nineteenth century, scientists believed that heat itself was actually a substance. This is known as the caloric theory.

The gas of “heat”, scientists believed, would evaporate from a hot substance, thereby cooling it. It would flow from a hot object into a cooler one. Many of the predictions arising from caloric theory actually hold true, and a lot of scientific progress was possible in spite of this fundamental misunderstanding. Caloric theory even had proponents up until the late nineteenth century, at which point the mechanical theory of heat was established beyond dispute.

This list has made many mentions of absolute zero. We’ve even mentioned it on Listverse before. But what about the other end of the scale? How hot can things get? The short answer is that we don’t know for certain; and it’s a question at the forefront of modern fundamental physics.

The hottest temperature commonly mentioned in science is known as the Planck Temperature. It’s the hottest temperature believed to have occurred in the universe, a mere fraction of a moment after the Big Bang. It’s about 10^32 Kelvin. To give you some perspective, that’s about ten billion billion billion times hotter than the temperature mentioned earlier, which was itself 250,000 times hotter than the core of the sun. And you thought your bath water was hot. The Planck Temperature is the highest temperature possible, according to the Standard Model. Any hotter, and conventional laws of physics begin to break down.

It’s possible that temperature might continue to increase even after this point; and we simply don’t know what would happen if it did so. Anything hotter than that is basically too hot to exist in our current model of reality.

Alan is an aspiring writer trying to kick-start his career with an awesome beard and an addiction to coffee. You can hear his bad jokes by reading them aloud to yourself from Twitter where he is @SkepticalNumber or you can email him at [email protected].