Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

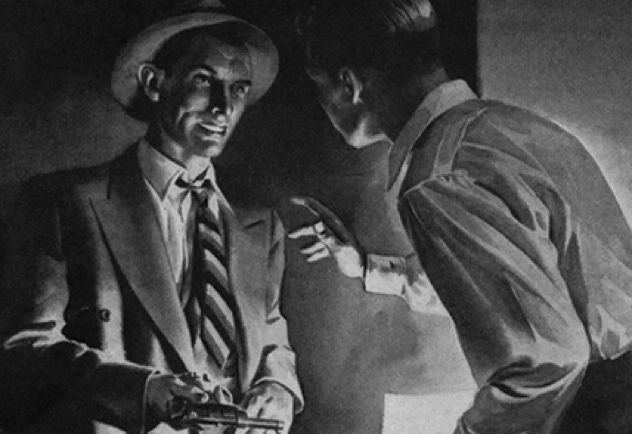

10 Nazi Spies and Their Espionage Plots In America

Even before U.S. involvement in World War Two, Nazi strategists—including Abwehr, the German intelligence agency—began inserting operatives into American cities or turning German-American citizens to the Nazi cause. The practice continued throughout the war. While there were some notable successes, especially prior to American involvement in the war, there were also some spectacular failures. Here are ten German spies and their plots, which occurred on U.S. soil during the 1930s and 1940s.

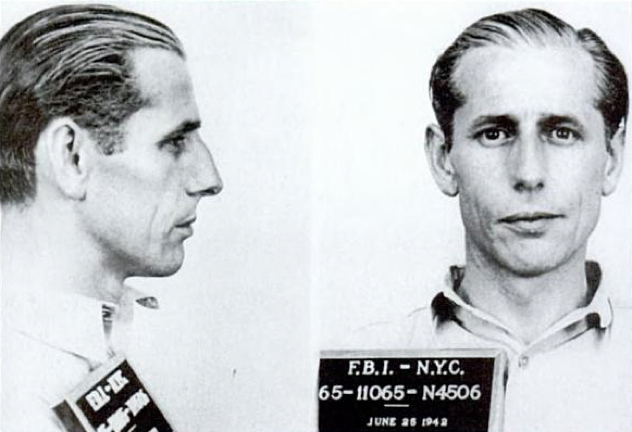

In June 1942, German submarine U-202 carried a small group of would-be saboteurs to a position off the coast of Long Island, New York. The four spies, led by George John Dasch, were expected to perform acts of violence including blowing up bridges, railways, and factories in New York City and the East Coast over a planned two year period. Dasch and his men comprised half of the assignment known as “Operation Pastorius” (see #4 for the other half), Hitler’s pet project which his intelligence advisors told him didn’t have a chance of success. The chosen men were inexperienced, and had very little training in intelligence operations.

The mission didn’t get off to a great start. The U-boat became stuck on a sandbar off Amagansett. Heavy swells made getting to shore in an inflatable raft an extremely hair-raising prospect. The men barely had enough time to bury their supplies—explosives, blasting caps, and timers—and strip out of their uniforms, when a Coast Guard patrolman, John Cullen, almost literally stumbled over them. A nervous Dasch lost his cool, threatened Cullen, and forced a significant cash bribe on him to keep his mouth shut.

Cullen did no such thing. He reported the suspicious incident. A little digging on the beach turned up four crates of explosives and equipment, German uniforms, and the stubs of German cigarettes. The FBI was brought into the case, and a search of Amagansett and Long Island began, but Dasch and his group had already made their way to New York City.

While the other three Nazi spies hid out in a hotel, Dasch went to Washington, DC, where he turned himself in and rolled over on his fellow saboteurs. He got a sentence of thirty years in prison, instead of being executed like six other members of the ill-fated Operation Pastorius. He received clemency in 1948, and was deported to West Germany.

In November 1944, two German agents were landed in America—not to commit sabotage this time, but to gather intelligence on U.S. military ships, aircraft, and weapons. If possible, they were also to cause delays in America’s development of the atomic bomb. The spies were Erich Gimpel, a native of Germany and former Abwehr courier who spoke English, and William Colepaugh, an American of German descent, a Nazi sympathizer, and a shady character who had little experience of spy craft.

German submarine U-1230 dropped Colepaugh and Gimpel ashore near Bar Harbor, close by Hancock Point, Maine. Their clothes weren’t suited for the cold New England weather and the falling snow, but they managed to walk from the beach on back roads carrying their expensive new luggage full of fake IDs, guns, cameras, cash, and diamonds to a railway station, where they took a train to Boston and then to New York City.

Once in NYC, rather than getting down to the business of spying and surreptitious activities, the unstable and alcoholic Colepaugh began a spree of drinking, partying, and womanizing, much to Gimpel’s vocal disgust. In one month, Colepaugh ran through $1,500 of the money they’d been given for operating expenses. Shortly before Christmas, Colepaugh abandoned Gimpel and absconded with the rest of the money—more than $40,000—and a female companion of dubious repute, ending up at an expensive hotel.

After a final drunken binge over the holiday, Colepaugh turned himself in to the FBI on December 29. Neither he nor Gimpel had done any actual spying during their brief time in NYC. Colepaugh told authorities everything he knew, including where to find Gimpel.

Despite his cooperation with the American government, Colepaugh was tried in a closed military tribunal with Gimpel. Both men were sentenced to death, but the end of the war delayed the executions and the sentences were commuted to life imprisonment. Gimpel was released in 1955 and returned to West Germany to write his memoirs, while Colepaugh was granted parole in 1960, and settled down to a quiet life in Pennsylvania.

Born in Germany, Maximilian Gerhard Waldemar Othmer came to the U.S. in 1919. The affable, likable man became a naturalized citizen by 1935, married an American woman, and settled down with his family and a temporary job as a vacuum cleaner salesman. Despite the fact that he made frequent trips to Germany, no one guessed that Othmer was a sleeper agent for Abwehr.

He became involved with the pro-Nazi German-American Bund, eventually becoming the leader of the Trenton, New Jersey, branch while working in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. After establishing himself as a hard-working, average guy, he got a job at Camp Pendleton (Norfolk, Virginia) military base, on the orders of German intelligence. In this position, he was able to send information to his handlers in Germany about British and American military vessels, convoys, and merchant ships in the port as well as Allied ship movements. In 1942, he was transferred by the Army to Knoxville, Tennessee.

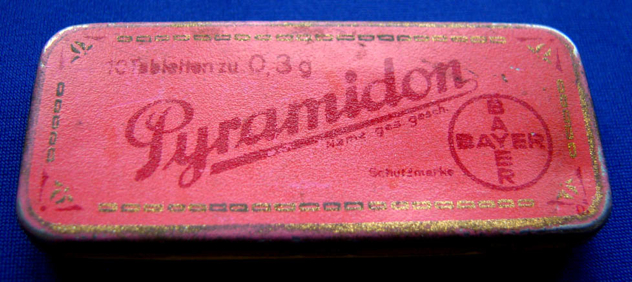

An ongoing FBI investigation into Othmer, due to his open Nazi sympathies, proved inconclusive. By 1944, a new FBI investigation turned up some crucial facts—including Othmer’s unusual request to a New Jersey dentist for Pyramidon, a common European painkiller used by Abwehr agents as an ingredient in invisible ink. He was brought in by the FBI’s Knoxville division for questioning, and immediately confessed to being a Nazi espionage agent. He’d been sending information written in code in invisible ink to his handlers, but he denied sending any letters after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Othmer refused to name other agents, but he did turn over a microfilm containing a code he used when communicating with Abwehr, which was linked to other espionage cases. He was tried as a spy, convicted, and sentenced to twenty years in prison.

Born in Chicago, Illinois to an Austro-Hungarian father and raised in Germany, Guenther Gustav Rumrich returned to America in 1929 and served in the U.S. Army’s Medical Corps in Panama until his desertion in 1936.

He became suspected in 1938 of possible spy activities because of Mrs. Jessie Jordan in Dundee, Scotland. She was a woman under surveillance by Britain’s intelligence agency, MI-5, who believed her to be an operative working for the Germans by acting as a mail drop, passing letters to and from a Nazi spy ring in New York City. Mrs. Jordan’s communications with “Mr. Crown” were intercepted by MI-5. As it turned out, Crown was Rumrich’s code name, and the letters were orders and instructions from his Abwehr handlers.

The head of MI-5 turned the information over to the FBI. Rumrich was put under federal surveillance, and a trap was set—but he didn’t fall for it. Instead, in February 1938, he called the Passport Office in NYC. Masquerading as the U.S. Undersecretary of State, he requested thirty-five blank passports be sent to his address. The suspicious clerk he spoke to over the phone reported the incident to the authorities. Rumrich was arrested in what became America’s first major prewar espionage case.

Rumrich supplied information about his fellow agents, who were also arrested. At their trials, he acted as a witness for the prosecution. For his cooperation, he was given a light sentence of two years in prison. Unfortunately, more important Nazi spies escaped the FBI’s net, and the case was not considered to be a complete success. The New York spy ring case pointed out America’s vulnerability to foreign espionage efforts, and prompted government action.

The Rumrich case was fictionalized in the 1939 film, Confessions of a Nazi Spy.

Born in Vienna, Austria, to wealthy and respectable parents in 1914, Lilly Stein’s early activities included exhibition ice skating and tennis. However, her contacts with Viennese café society, separation from her family, and possibly her affair with an American career diplomat and U.S. State Department official, Ogden H. Hammond, Jr., led the willowy and buxom brunette socialite to be recruited by Abwehr as an intelligent agent.

In 1939, Lilly was sent to New York City, where she opened a dress shop with new friends. She recruited agents for Abwehr and acted as a forwarding address, successfully moving letters containing orders or sensitive stolen information to and from Germany for fellow spies. Her affair with Hammond continued, though she later claimed that their relationship was “purely platonic.” According to the FBI, Lilly was a cautious spy; she put nothing in writing and carried nothing incriminating on her person except the occasional microfilm.

The dress shop venture soon failed, however, and the pay from her Nazi handlers was usually late, often leaving her scrambling to pay the rent. To make ends meet, she worked as an artist’s model. It wasn’t long before her constant complaints and demands for money tested Abwehr’s patience to the limit—eventually forcing them to cut her loose from their operations.

Lilly was rounded up in June, 1941, as part of the infamous Duquesne spy ring (see #1). Despite her assertion that she was forced into the espionage business because she wasn’t purely Aryan—and therefore faced being put in a forced labor camp, deported, or worse when the Nazis took Austria if she refused to cooperate—she received a ten year prison sentence.

Although he moved to New York City in 1927 at the age of twenty-five and worked towards naturalization for years, Hermann W. Lang always remained loyal to the country of his birth: Germany. That loyalty would lead him to acquire valuable intelligence for the Nazi spy agency, Abwehr, after he was recruited during a visit home in 1938.

A draftsman by trade, Lang worked in a factory for the Carl L. Norden Corp., which manufactured top secret U.S. military and defense equipment and materials. One of their most guarded projects was an improved bombsight for the Navy and Air Force—considered so vital to U.S. interests that the fact of its existence was kept under lock and key. Not even America’s closest allies, including Britain, were given access to the Norden bombsight, since the government wished to maintain the country’s neutrality at the beginning of war in Europe.

As a factory inspector, Lang had access to the bombsight’s blueprints. Company policy forbade anyone from taking the blueprints out of the office, but he managed to sneak a set home and make a copy, which was later smuggled to Germany in an umbrella carried by another agent on a passenger cruise liner. Lang continued to work at his job and send other details via a German network until he was arrested as part of the Duquesne spy ring operation.

He pleaded guilty, and received a sentence of twenty years in prison. During the trial and its aftermath, prosecutors and government spokesmen assured the public that the Norden bombsight hadn’t been entirely betrayed to the Germans and the secret remained safe. They claimed no one person at the factory had access to the full plans. However, it’s been noted the bombsight used by the Luftwaffe after 1938 bore a resemblance to the one stolen by Lang.

In Adolph Hitler’s planned Operation Pastorius, two groups of >Nazi saboteurs were landed on American shores in June 1942.

Like their counterparts, the mission of the Ponte Vedra foursome was simple: commit acts of sabotage and terrorism such as blowing up railways, locks, and canals; plant suitcase bombs in Jewish owned shops; and destroy New York City’s water system. The Florida group was led by John Edward Kerling, a German who had lived in America for years before returning to his homeland. These men didn’t have much training in spy craft, apart from some basic knowledge on how to set explosives. Regardless, they carried a fortune in cash and crates of equipment, which they buried in the sand on the beach where they came ashore.

They took a bus to downtown Jacksonville and then traveled to Cincinnati, Ohio, without incident, where they waited as instructed to rendezvous with the Long Island team headed by George Dasch. Unknown to Kerling, Dasch had blundered, causing his team to be arrested by the FBI, and he told the federal authorities everything he knew, including the when and where of his scheduled meeting with Kerling’s sabotage team.

Kerling and his three men were arrested, tried before a military tribunal, and executed by electric chair in August 1942, along with two from Dasch’s group.

After serving with the German Army in WWI, Dr. Griebl—an obstetrician and surgeon—immigrated to the United States in 1925 and, after becoming a citizen, resided in New York City in Manhattan’s Yorkville district. Here, he became a community leader and a member of the U.S. Army Reserve. However, the apparently respectable doctor harbored a dark secret: he’d worked as an Nazi undercover agent since 1934.

By means of his diligent work, social contacts, and loyalty to the Nazi cause, Griebl gained the trust of Abwehr to such an extent that he became the primary coordinator and head of a widespread spy ring operating across the country. Information flowed from German intelligence agents in other cities like Boston, Norfolk, and Baltimore, directly into Griebl’s hands. He also sought out engineers with German-American backgrounds, and recruited them as moles to betray secret technical military and defense plans. Since no single federal agency in the U.S. had charge of investigating subversive acts, he was able to run his operation for years with virtual impunity, undetected. For his dedication, he received generous payments and an honorary commission as a captain in the Luftwaffe.

In 1938, one of his New York spies, Guenther Rumrich, was arrested by the FBI—and during his confession, he gave up Griebl’s game. In turn, after he was brought in for questioning, Griebl betrayed everyone in his network, naming names and offering details so readily that the FBI chose to release him, assuming he’d show up for the federal grand jury hearing.

He didn’t. The doctor wasted no time boarding a ship to Hamburg and escaping the United States. He eventually settled in Vienna, where he re-opened his medical practice, and did no further spying for Nazi Germany. As an interesting sidenote, Griebl was the only person to hold simultaneous commissions in both the U.S. and German military services.

An often-depressed, unmarried loner who seemed a bit of a harmless kook according to his co-workers, Guellich was actually a Nazi agent working for Ignatz Griebl’s spy network, and stealing America’s secrets through his job in a New Jersey shipyard.

The German born Guellich came to America in 1932, and was recruited by Griebl in 1935 due to his work as a metallurgist at the Federal Shipbuilding Co. in Kearney, NJ. Because of his position in the laboratory, Guellich had access to secret and restricted projects developed for the U.S. Navy, including guns and shells, destroyer blueprints, and samples of cables used on ships. The material was sent to Griebl, who forwarded it to Germany. It wasn’t long before Guellich’s diligence earned him a top spot in the Nazi spy network.

A report crossed Guellich’s desk detailing work by Robert H. Goddard, a pioneering rocket-propelled missile researcher. He sent a copy to Griebl. Berlin received the report with great interest, and ordered Guellich to obtain more information. He traveled to Goddard’s laboratory in Roswell, New Mexico to observe a test launch of the Nell missile. Guellich’s continued ferreting-out of secrets assisted German scientists in developing their own rockets.

Guellich was betrayed by Griebl following the latter’s arrest by the FBI. Like the other spies in the New York ring, he received a light sentence despite his espionage.

Admittedly, this one’s claim to a place on this list is a little tenuous—but given its relation to many of the spies mentioned already, it seems fitting to include the matter here.

South African Frederick “Fritz” Duquesne’s hatred of Britain, which had its origin in the Boer Wars, caused him to become a turncoat and spy for the Germans in WWI. He saw no reason to switch his loyalties when he moved to New York City and became a naturalized U.S. citizen. He eventually volunteered as a spy for Abwehr. Working at 120 Wall Street, Duquesne set up an extensive professional espionage network, collecting information from Nazi agents and moles at strategic locations in the United States.

Unknown to Duquesne, the Gestapo and Abwehr attempted to recruit another potential spy, William Sebold—a native German who had become a naturalized U.S. citizen—during his visit home in 1939. His family still lived in Germany. Afraid they might face reprisals if he refused outright, Sebold agreed to be a Nazi spy, but as soon as possible, he quietly went to the U.S. Consulate in Cologne and offered his services to America as a double-agent.

After returning to the U.S. in 1940, Sebold assisted the FBI in setting up a surveillance operation against Duquesne’s spy network. With his cooperation, federal agents were also able to use his assigned codes to send disinformation by shortwave radio to Abwehr.

In December 1941, just six days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI began arresting members of the Duquesne spy ring, including Fritz Duquesne himself—reaching a total of thirty-three spies in all. The operation was the largest round up of foreign intelligence agents in America. Some pleaded guilty, others went to trial—and all were convicted.

William Sebold, however, disappeared—and his fate remains uncertain. Some believe that he was given a new identity to protect him from Nazi revenge. The 1945 film, The House on 92nd Street, is a fictionalized account of William Sebold and the Duquesne spy ring.