Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Yet Another 10 Lesser-Known Hoaxes

Examples of people falling prey to con men and pranksters are clearly found throughout human history. Whether it’s due to gullibility, preconceived notions, or wishes of better lives, people continue to become victims. Here are yet another 10 lesser known hoaxes.

10 Clever Hans

During the end of the 19th century and the early 20th century, members of the German public were taken in by an extraordinary horse named Clever Hans. According to his owner, Wilhelm von Osten, the horse could perform advanced intellectual tasks such as mathematics. Though previous experiments upon bears and cats had proven unsuccessful, Osten was positive he could teach an animal mathematics. Sure enough, Clever Hans demonstrated the ability to stomp out with his hoof the answer to the problem Osten had written on a chalkboard. Success!

Not quite. The animal was examined by Carl Stumpf, a philosophy professor, who initially determined the phenomenon to be real. However, Stumpf and one of his students, Oskar Pfungst, examined Clever Hans more thoroughly and figured out how the trick was done. Von Osten was unconsciously giving the horse subtle clues with his body language, which Clever Hans was responding to. Granted, von Osten may not have meant for his research to be a hoax, but that it was.

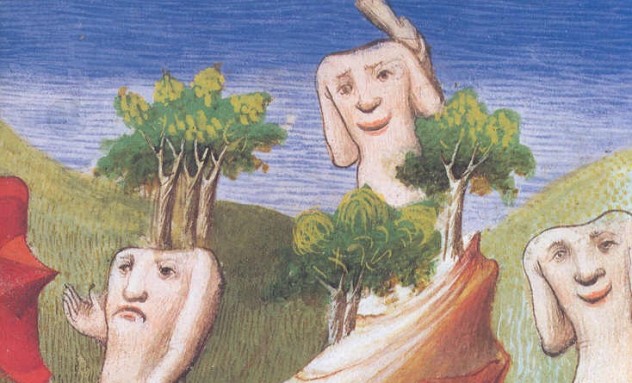

9 The Travels Of Sir John Mandeville

Written by the hand of an unknown author in the 1300s, the narrator of the book claims to be a knight of St. Albans named John Mandeville. In 1322, Mandeville left on an epic journey, traveling through the Middle East, China, India, and finally Mongolia. It was there that he served 15 months in the army of the Great Khan.

The thing is, nobody can seem to track down this mysterious knight. Jean de Bourgogne, a local physician in an eastern Belgium town called Liège, was said to be the story’s author, but that claim has since been discredited. His name cropped up because of the medical nature of some of the writing. A number of mythical places were named as destinations visited by Mandeville, including Prester John’s kingdom, the abode of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, and an island inhabited entirely by dog-headed people. It’s also not known exactly how the book was received and whether or not the people of the Middle Ages took it as fact, but folks were pretty gullible back then.

8 The Papal Bull Of John V

John V, the very last Count of Armagnac of his house, was described as follows: “His physical appearance was not attractive” and he was short and stocky. He was also unmarried at the age of 30, nearly unheard of by a noble in that time. There was a reason for this besides his unappealing visage: John V was involved in an incestuous relationship with his sister, Isabella, who was described as one of the most beautiful women in France.

After two children were born out of the relationship, John V and Isabella promised to refrain from sleeping together anymore. That turned out to be a lie, as they had a third child shortly after. When she was born, her parents were faced with ex-communication by Pope Pius II. However, seemingly out of nowhere, a papal bull from Pius II’s predecessor, Callixtus III, arrived to bless the union. Seems pretty convenient, doesn’t it? Indeed, it was later revealed to be a hoax, created by John V and a crooked bishop in Cambrai named Antoine d’Alet. He was banished from the country, but apparently incest only earned you a few years of exile in medieval France.

7 The Virgin Birth Of Magdeleine d’Auvermont

Magdeleine d’Auvermont was a woman who lived in Grenoble, France in the 1600s. After being away from her husband for four years, she gave birth to a child named Emmanuel, leading her family to bring her to trial for adultery. While testifying, d’Auvermont gave the following excuse: the child really was her husband’s, having inseminated her during a dream she had. A group of mothers, midwives, and doctors were brought in, all supporting her claim of supernatural impregnation by saying that they themselves had experienced the same thing in the past. She was found innocent of the charge and the baby was declared legitimate.

Just a few months later, after they received the verdict, the Parliament of Paris pronounced it to be an elaborate hoax. A number of clues, including the child’s name, the mother’s story, and the fact that the sentence was given on Carnival, led them to believe that none of the people involved ever really existed.

6 De Situ Britanniae

In 1747, a 24-year-old Englishman named Charles Bertram wrote to a famous antiquarian and disclosed the fact that he had discovered an ancient manuscript called De Situ Britanniae, as well as a map, purported to be the work of a 14th century monk who collected the writings of a Roman general. Examined thoroughly by some of the top paleographers of the time, it was deemed to be a genuine article. Over ten years later, the work was finally published, and it had a great effect on a number of historians up until the 19th century. The book was renowned for its detail about Britain during the Roman Empire, especially in regards to Scotland, an area which had been scarcely mentioned in the existing historical archives.

In the late 1800s, Bernard Woodward, the librarian of Windsor Castle, published a series of articles in Gentleman’s Magazine challenging Bertram’s claims with a number of reasoned arguments. He postulated that much of Bertram’s information was gleaned from other sources or simply made up. It was finally debunked by J.E.B. Mayor, the librarian of the University of Cambridge, who published a 90-page argument against De Situ Britanniae two years later.

5 Princess Caraboo

On April 3, 1817, a family in Gloucestershire, England was treated to an mysterious guest: a woman with black hair, dark eyes, and a turban. Speaking in a dialect unknown to the English, but apparently known to a Portuguese sailor, she claimed to be from an island called Javasu and she was a princess from that island named Caraboo. She was originally imprisoned for vagrancy but released when her story came out. The local magistrate, Samuel Worrall, let her stay at his house for 10 weeks, where she swam naked, dressed in exotic clothing, and prayed to a god named Alla-Tallah.

Eventually, her true identity was discovered by a boarding house keeper named Mrs. Neale, who recognized her as a cobbler’s daughter from Devonshire, England named Mary Baker. She was sent to America by the Worralls in order to avoid further scandal, and she remained there for a number of years before returning to Europe, where she continued her scam with limited success. The story, slightly embellished, was turned into a movie in 1994, starring Phoebe Cates as Princess Caraboo.

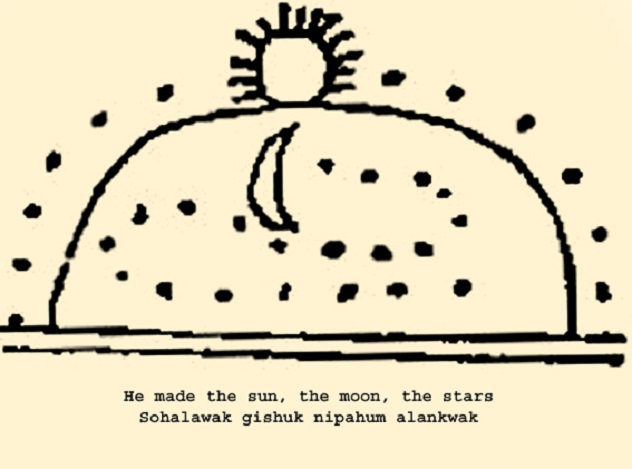

4 The Walum Olum

Constantine Rafinesque was a sort of Renaissance man of 19th century Europe—he contributed to a number of fields, including botany, zoology, and Mesoamerican linguistics. However, in 1836, he also joined the ranks of famous pranksters with his work titled The Walum Olum. It was said to be a translation of a series of pictographs, detailing the entire history of a tribe of Native Americans known as the Delawares.

Rafinesque claimed the pictographs were on strips of birch bark, which were never seen by anybody else. A number of details were European in nature, namely the creation of the world by a male deity, a constant battle between good and evil, and the migration of the native people over an Asian land bridge. These dubious characteristics revealed the work as a hoax. However, it wasn’t definitive until 1996, when researcher David Oestreicher published his work exposing the lies.

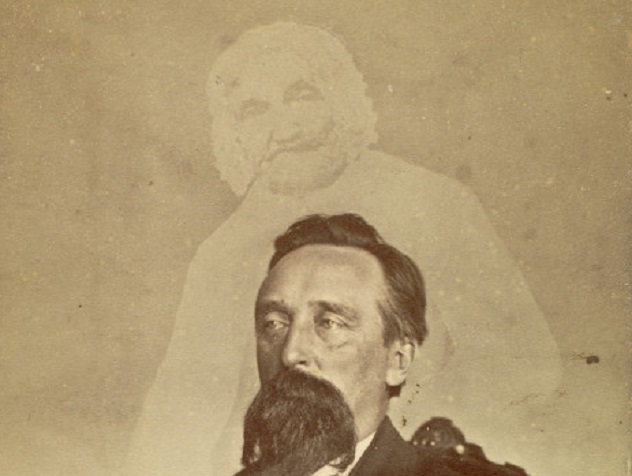

3 William Mumler’s Spirit Photography

In the mid-1800s, as photography was becoming more widespread, a man named William Mumler took advantage of a little-known quirk of the early machines. By exposing the plates twice, Mumler could make it look as if ghosts appeared next to the living. Due to the tremendous loss of life during the American Civil War, people were all too ready to have a reminder of their loved ones, and Mumler’s services were in high demand.

The hoax was exposed when a man named Joseph H. Tooker went to see Mumler under a false name and was given a photograph with a ghostly image said to be his father-in-law. The man was not known to Tooker and he refuted Mumler’s claims, leading to a trial for fraud. A number of people were brought in on both sides, including circus showman P.T. Barnum for the defense, who hired a reputable photographer named Abraham Bogardus to replicate the spirit photographs. Although Mumler was found innocent, his work was deemed worthless.

2 Gordon Gordon

Jay Gould, the 19th century railroad developer and purported robber baron, was once tricked by a British con man named Lord Gordon Gordon. The man was first identified in 1868, when he convinced a number of investors to finance his lease of an estate after claiming he was coming into a large amount of money. Fleeing to America, he met up with Jay Gould and convinced him that he had 60,000 shares of Erie Railroad, a rival railway company. The railway baron was planning on taking control of the company and he fell for Gordon’s trick. (The company was at the center of a fierce competition known as the Erie War, a conflict between prominent American financiers, including Gould and Cornelius Vanderbilt.)

Gordon managed to get $1 million from Gould in exchange for the fake stocks before fleeing to Canada when his lies were uncovered. Bounty hunters, working for either the bondsmen or Gould himself, attempted to kidnap Gordon and bring him back to America. They were arrested short of the border, because they had illegally entered the country, and tensions were high for a while, until the Canadians released the kidnappers. A little over a year later, Gordon’s British past caught up to him and he was set to be arrested and returned to Britain. However, he shot himself in the head to avoid the punishment sought by his victims.

1 Henry Friend’s Electric Sugar

In 1884, self-proclaimed professor Henry Friend founded a company using a secret process he devised to refine sugar using electricity. The process was said to be much faster than the current methods, as well as extremely cheap. Nearly $1 million was invested in the company—but the whole process turned out to be an elaborate hoax.

It eventually collapsed a few years after its founding when Mr. J. U. Robertson, the treasurer of the company, revealed in a letter that the president of the company, Mr. W. H. Cotterill, had confronted Friend’s widow about what he saw during a trip to their “factory.” It was discovered during this trip that all of their raw sugar inventory had simply been stored in a hidden room and the “refined” sugar had just been bought at a store. Olive Friend and her parents, who were in on the scheme, were convicted on a number of charges and each spent time in jail as a result. None of the money was every recovered—in fact, Olive and her mother returned to the house they built using the stolen money.