Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Notable Last Survivors Of Historic Events

The last living witnesses to historical events are fascinating in so many ways. Not only are they time capsules of memories, experiences, and stories from a bygone era, they also hold in them the last remaining memory of that great event. When they die, that event passes from living memory into history. What is it like to be able to look back on 60, 70, or 80 years of life since that event and think “I am the last”? These 10 people know.

10 Mae Keene

The Last Living Radium Girl

Things were looking up for young women in America in the early 1920s. They had finally received the right to vote and they were entering the US workforce in larger numbers than ever. In particular, American companies wanted to employ young women in manufacturing operations that required precise yet repetitive work, such as hand painting radioactive radium paint onto clock faces. Radium was discovered in 1898 by Marie Currie, and four years later, William Hammer mixed radium with zinc sulfide to make radioluminescent paint. Before long, anyone and everyone had to have a radium-painted watch on their hand or a radioactive, glowing clock by their bed. Many companies rushed into the business of processing the radium, making the radium paint, or manufacturing the clocks and watches with the painted parts.

In 1924, 18-year-old Mae Keene went to work at one of these manufacturing plants, the Waterbury Clock Company of Vermont. Like the other young women who painted the clocks, she was taught how to obtain a fine point on her brush by moistening the tip with her lips. This meant ingesting radioactive radium each time they touched the painted brush to their mouth. The women were told the radium paint was safe, and to be fair, it wasn’t until the 1920s that the companies knew they were lying. The women would even sneak the paint out of work and use it to paint their nails.

Mae quit the job after only a few months, and that probably saved her life. Unlike so many of her coworkers, she did not develop the deadly diseases caused by radium such as “radium jaw,” a debilitating and usually fatal disease where radium attacks the bones and rots away the jaw. In fact, Mae lived to be a very old woman. Today, at the age of 108, she may be the very last living radium girl.

9 Werner Franz

The Last Living Crew Member Of The Hindenburg

Everyone has heard of the Hindenburg. The gigantic German passenger aircraft exploded, burned, and crashed at Lakehurst, New Jersey on May 6, 1937. It seems incredible anyone could walk away from that fiery crash, but of the 97 crew and passengers on board, 62 would survive. Today, 77 years later, that number is down to one. Werner Franz was a 14-year-old cabin boy on the Hindenburg and is the only living crew member from that historic event.

As a cabin boy, he worked from 6:30 AM until 9:30 PM serving the ship’s officers and crew. His job was to prepare the messroom for all meals and serve the crew coffee at night. By the time he was on his first voyage to the United States, Franz had been to South America aboard the Hindenburg several times. He had his job down to a routine. The evening the Hindenburg approached the tower in Lakehurst, Franz was still busy washing and putting away dishes in the mess.

He was lucky to be where he was, toward the front of the ship. Just as he was putting away a coffee cup, he heard a noise. The entire ship shuddered and sank at the stern, lifting the bow upwards. He ran out of the mess to the gangway, where he saw a ball of flame rushing towards him as the hydrogen cells exploded and burned. Just then, he was doused with water as the forward water ballast tank shifted and poured water toward the rear of the ship.

The water helped prevent Franz from being burned, but how to escape this burning ship? He remembered the provision hatch used to transfer stores onto the ship. He ran to it, sat down on a beam—with the glow of the burning ship all around him—and he kicked open the hatch. Franz looked down and saw the ground rushing up toward him. He waited until the Hindenburg was close to the ground and jumped. Just then, Franz caught his last lucky break As he hit the ground, the ship lurched back up into the air. This gave him just enough time to run out from underneath the falling immensity of the burning ship.

Franz would survive wet, uninjured, and alive. Later, Franz asked for permission to return to the Hindenburg to look for a watch his grandfather had given him. Amazingly, he found his watch in the burned and twisted wreckage.

8 John Cruickshank

Last Living Victoria Cross Winner For Action During World War II

The highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces is the Victoria Cross. Today, John Cruickshank is the only living World War II combatant to have won this prestigious military award, and boy did he earn it.

John Cruickshank was the pilot of a PBY Catalina airplane whose mission it was to seek out and destroy German U-boats during World War II. It carried six 113-kilogram (250-lb) depth charges to get the work done. On his 48th mission and cruising at 610 meters (2,000 ft) above the Arctic Ocean, he and his crew spotted U-347 on the surface and moved in for the kill. They came in low over the U-boat, but the depth charges failed to drop.

The PBY circled around to come in again, but the element of surprise was lost and the Germans were ready for them with their deck guns. As they brought the PBY in low for a second attack, the Germans opened fire. Bullets and shells from the U-boat shredded the PBY, killing one man and wounding several more. Cruickshank took the worst of it, having been hit an incredible 72 times. Riddled with bullets in his limbs and lungs, he held the PBY steady and dropped all six depth charges, sinking the sub.

The injured crew now had to fly the badly damaged PBY five hours back to their base in Scotland. Bleeding and lapsing in and out of consciousness, Cruickshank refused morphine so he could fly the plane if needed. It was a smart choice, because when the PBY reached its base, the copilot could not land it. Cruickshank took the controls and landed the PBY on the water, keeping the front of the plane above the waterline long enough for the flying boat to reach shallow water.

7 Reinhard Hardegen

The Last Living German U-Boat Captain

Fortunately for Captain Reinhard Hardegen, he was not on U-347 when John Cruickshank and his PBY crew sank it. If he had been, today he would not be the last living German U-boat commander. In many ways, Hardegen was the peer of Cruickshank. He wasn’t just the pilot of his war machine, but the winner of a prestigious war decoration from his country, the coveted Knights Cross.

Hardegen was the captain of U-123 and was one of the most successful killers of Allied vessels and crews in the entire war. Like all German submariners, he was exceptionally proud of the German U-boats, believing them to be far superior to those of the Americans. Hardegen recalled visiting an American submarine before the war and coming away with the impression that the American submarines had great creature comforts and spacious room compared to the German subs, but were not as well-designed as ultimate fighting machines. He also felt the discipline and devotion to duty of the German submariners far exceeded that of their American counterparts.

The Germans demonstrated their dedication to killing during Operation Drumbeat in the first six months of 1942, when German U-boats sank Allied ships in what another German U-boat commander called a “duck shoot.” The Germans called this period of their submarine war “the Happy Time” as they sank Allied vessels along the North American coast almost at will.

Hardegen would sink more Allied ships than any other U-boat commander during Operation Drumbeat. He contributed to the loss of 500 Allied ships and 5,000 merchant mariners. The Happy Time would soon give way, however, to what the German submariners called “the Sour Pickle Time,” the period in 1943–1945 when Allied sub detection and killing technology made almost every U-boat mission a death sentence. Hardegen survived the Sour Pickle Time and the war itself. At the age of 101, he is the last of the World War II German U-boat commanders and one of the last living German submariners.

6 David Stolier

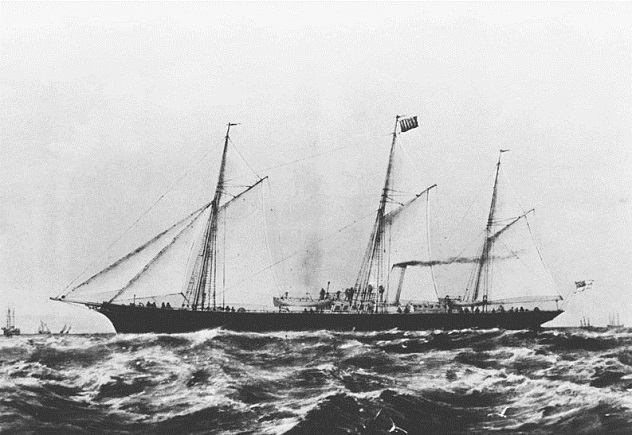

The Last Living Survivor Of The Struma Disaster

In 1936, with his home country of Romania increasing their persecution of Jews, the father of David Stolier decided it would be best to evacuate his son from the country. He booked David passage on the Struma, an old cattle boat that was barely seaworthy, bound for the assumed safety of British Palestine. Badly overcrowded, with almost 800 passengers and crew, the Struma barely made it to the port of Istanbul, Turkey. The ship sat there for two months while the Turks refused to allow the passengers to disembark and the British refused to grant them visas to reach Palestine.

Years later, Stolier would recall the awful conditions on board the Struma. Hundreds of passengers baked in the sun with no room to move and little water or food. In February 1942, the Turks finally forced the Struma back out into the Black Sea with nowhere to go. Within hours, a Soviet submarine patrolling for Axis ships mistakenly torpedoed the Struma only a mile off the coast. Out of 769 Jewish passengers, including 75 children, David was the sole survivor. Seventy-two years later, Stolier is still the last living witness to this historic tragedy.

5 Harry Ettlinger

The Last Monuments Man

Not every old man gets the opportunity to meet George Clooney, let alone see his World War II story told by the A-list actor and director in a major motion picture. But 88-year-old Harry Ettlinger has accomplished that and much more in his long life. He also holds the distinction of being the last of the Army unit dispatched to Germany to save the looted art masterpieces the Nazis had hidden away in caves and . . . other places.

For those who don’t want to wait to watch Clooney’s The Monuments Men, the trailer is above. At the very end of World War II, the Allies were afraid the Germans would destroy unknown numbers of priceless and historic artwork they knew the Nazis had seized when they came to power at the start of the war. The question was, where was the art hidden and could they rescue it in time? To that end, the Allies dispatched a small unit of art historians, professors, and other Indiana Jones characters called the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives corps. They were tasked with finding and recovering the stolen art the Nazis had stashed in castles, salt mines, and other locations. Almost 70 years later, only Harry Ettlinger survives to attend the Hollywood premiere of the movie made to tell the tale of this remarkable World War II mission.

Ettlinger, a German Jew who had the good sense to flee Germany in the 1930s, would return to Europe at the very end of the war to help recover the artwork, much of it stolen from German Jews. Ettlinger and his comrades would recover a total of over 900 works of art. After the war, he went home to Newark, New Jersey and helped his country fight the Cold War by working for a company that designed nuclear weapons.

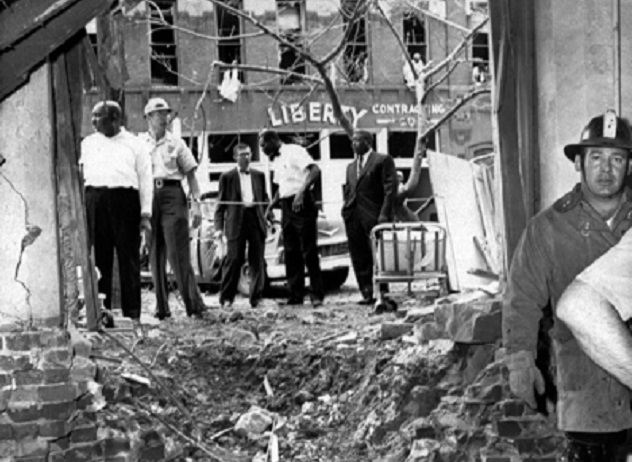

4 Sarah Collins Rudolph

The Last Living 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing Survivor

On September 15, 1963 at 10:22 AM, a bomb detonated in the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. The bomb was a case of dynamite planted by four Klansmen who had tunneled underneath the front steps of the church. Their cowardly act of domestic terrorism against the African-American church managed to kill four people, all of whom were little girls attending a Sunday sermon. Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley—all 14 years old—along with 11-year-old Denise McNair died in a failed attempt to stop the growing Civil Rights movement in the Deep South.

It would take over a decade for authorities to begin to track down the KKK members who planted the bomb. Afterward, these four girls were posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, but a fifth victim of the bombing that day has never been recognized. Sarah Collins Rudolph, younger sister of Addie Mae Collins, is the last injured survivor of that attack. She lost an eye to some flying glass and was in the hospital for months. She never really recovered, as she is still traumatized by the events of that day, but she is the only victim still alive 51 years later.

3 Donald “Nick” Clifford

The Last Living Sculptor Of Mount Rushmore

Drilling rock hundreds of feet up on the side of a cliff face is exciting work, especially when it’s a historic monument like the Mount Rushmore National Memorial in Keystone, South Dakota. It is also exceedingly dangerous work. Amazingly, no workers were killed during the years of drilling and blasting needed to create the monument. That fact is not lost on the last living man to drill and chisel the faces of four great American presidents into a mountain. Donald “Nick” Clifford has the distinction of being the last surviving person who actually worked on the sculpture. The story of how he got the job is almost as fascinating as the work he and the others did to create such a magnificent work of art.

Clifford had been hassling the sculptor of the monument, Gutzon Borglum, for a job since he was 15 years old. He finally got his chance at the age of 17 because of baseball. In 1938, Borglum’s son decided he wanted to form a baseball team for his workers. Knowing that Clifford was an excellent pitcher and infielder, he got added as a ringer to the team, which was called the Mount Rushmore Memorial Drillers. He then badgered his teammates until they finally got him a job.

At first, Clifford worked cutting logs and cranking winches to raise and lower cables at the rate of $0.50 per hour. He was eventually promoted to driller and given a raise of $1 per day. He worked three years on the project. Now, he autographs his own book, Mount Rushmore Q&A, at the Mount Rushmore gift shop and answers any and all questions about the making of the memorial. After all, he is the last one who can.

2 Alcides Ghiggia

The Last Living Winner Of The 1950 World Cup

In the world of professional football, Pele is probably the most well-known South American football player of all time. But there is one lesser known football legend from South America who is also the sole living member of his team—a team that pulled off one of the greatest upsets in football history.

It was the 1950 World Cup, played in host country Brazil. In the final game the home team faced an opponent from next door, the small country of Uruguay. There were 200,000 fans inside the world’s largest football stadium that was built just for the World Cup, rooting for Brazil. It seemed impossible for Uruguay to upset the home team.

Brazil only needed a tie against Uruguay to win the Cup and only an upset win could give it to Uruguay. Everyone was so sure of a Brazilian victory that local newspapers had already printed an announcement of the win the morning before the match. Uruguay’s coach bought every copy in their hotel’s newsstand and brought it back to the room for his team to pee on.

Brazil led much of the game 1–0 until Uruguay’s Juan Schiaffino scored to tie it at 1–1. Still, a tie was all Brazil needed—they just had to hang on. With only 11 minutes remaining, Uruguayan Alcides Ghiggia scored, winning the game at 2–1.

The massive crowd was stunned into silenced. Uruguay won the game and the Cup. The loss became not only part of Brazilian history, but also of the Brazilian psyche. It was and still remains known to this day as the Maracanaco, meaning “shock.” A noted Brazilian commented that every country has its own national catastrophe, and for Brazil, it was the loss to Uruguay in 1950.

The hero of that game, a legend in world soccer and especially in his home country of Uruguay, is the only survivor of that historic team. In 2013, still very much part of world soccer, Ghiggia was honored to be one of those at the final selection process of the 2014 World Cup match, which will also be played in Brazil. Ghiggia plans on being there—to root for Uruguay, of course. In 2014, Ghiggia will be one of only two people (the other being the president of Uruguay) who will be allowed to touch the coveted World Cup trophy as it travels through Uruguay to Brazil.

1 David Greenglass

The Last Living Rosenberg Co-Conspirator

On June 19, 1953, an American couple named Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Greenglass Rosenberg were executed for spying and handing atomic bomb secrets to the Soviets in a trial that was a defining moment in Cold War espionage history. Over 60 years later, only one of their major co-conspirators is left—Ethel Rosenberg’s brother, David Greenglass.

The spy ring began with a brilliant nuclear physicist who worked at the secret Los Alamos nuclear facility designing and building the first atomic bomb, Klaus Fuchs. In 1949, the Soviet Union exploded their first atomic bomb, years before they were expected to be able to. Fuchs was the scientist who fed US and Canadian atomic secrets to the Soviets that allowed them to shave years off their development of an atomic bomb. He confessed to spying and implicated a chemist named Harry Gold. Gold, who would be convicted of espionage and sentenced to 30 years in prison, implicated David Greenglass, a US soldier stationed in Los Alamos. Greenglass had been recruited by Julius Rosenberg through Greenglass’s wife, Ruth Greenglass. David Greenglass became a Soviet spy, passing on secrets through Gold and Julius Rosenberg to the Soviets.

Ruth Greenglass and Julius Rosenberg were both passionate communists, but Ethel Rosenberg did not seem to share her husband’s passion and did not appear to be involved in the espionage. Her only guilt seemed to be she was the sister-in-law of Ruth Greenglass. During the Rosenbergs’ trial, David Greenglass testified that Ethel Rosenberg had typed some of the secret documents he had passed along to the Soviets, thus implicating Ethel Rosenberg directly as a spy. Greenglass probably said this to save the life of his wife, who was not prosecuted, even though it appears certain Ruth recruited her husband to spy for the Soviets.

In exchange for his testimony, David Greenglass received a 15-year sentence instead of death. Greenglass would later recant his testimony, stating that Ethel Rosenberg did not type the atomic secrets, but it was too late. Ethel and her husband were put to death at Sing Sing prison for espionage. Many historians feel Greenglass’s testimony sealed her fate. In 2006, a federal judge in Manhattan ruled to keep the secret grand jury testimony of David Greenglass sealed until after his death.

Patrick Weidinger used a computer to research and type this list, but he is one of the last living survivors of an ancient time when research was conducted with printed materials and oral histories and typing meant using a typewriter.

![Top 10 Haunting Images Of Historic Tragedies [DISTURBING] Top 10 Haunting Images Of Historic Tragedies [DISTURBING]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/33758v-150x150.jpg)