Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

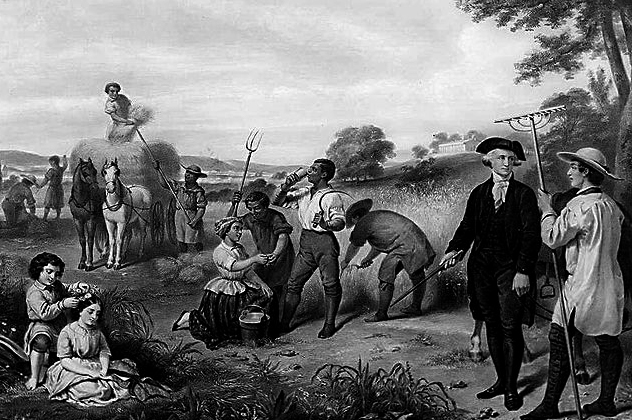

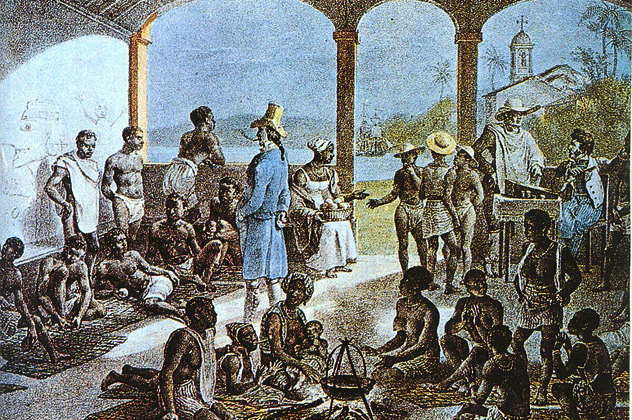

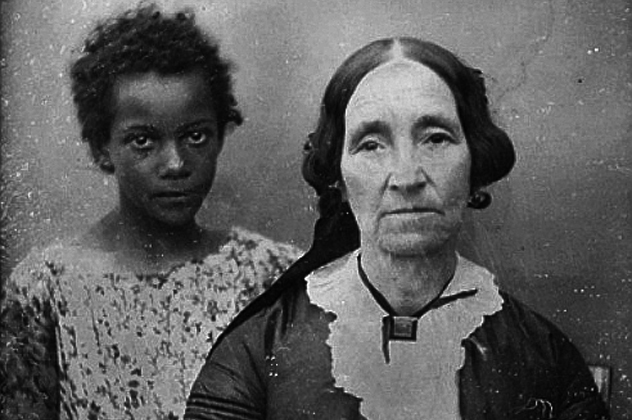

10 Stories Of Triumph Over Slavery In The American South

Courage and strength in the face of a system that’s designed to be as repressive as humanly possible is an amazing thing, and the stories of those who struggled against their oppressors can be truly inspiring. Here are just some of the stories of those living—and struggling—in the pre–Civil War South who took their lives and their fates into their own hands and won . . . although, sadly, some didn’t live to see the effect that their actions had on the world around them.

10Ellen And William Craft

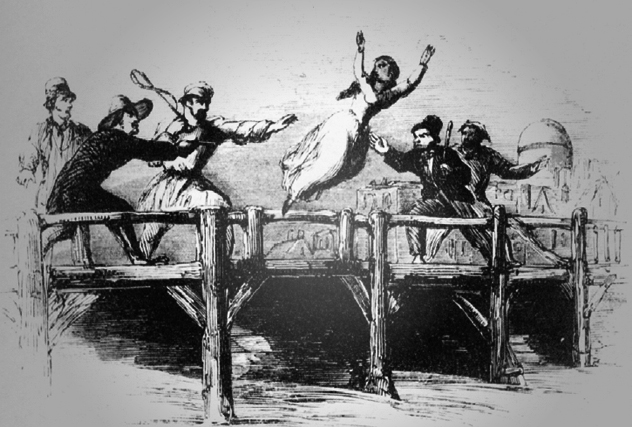

When Ellen and William Craft decided to escape their Southern masters and make a bid for freedom, they did it in an incredibly harrowing—and unbelievably brave—way: They did it in plain sight. Ellen, the daughter of a white plantation owner and one of his half-white slaves, had already spent much of her life being mistaken for a white family member (and getting the wrath of her masters for it). So when she and her husband decided to go north, Ellen cut her hair, wrapped bandages around part of her face, and donned colored spectacles and men’s clothes. She would be traveling as a man, with William posing as her slave. To hide the fact that she was illiterate, she put her arm in a sling as an excuse as to why she couldn’t sign her name.

Having gotten passes from their masters to go see family for the holiday, they headed to the train station instead, and their journey was far from easy. On the first leg of their trip north, Ellen was seated next to a close friend of her master’s, whom she had seen countless times; she pretended to be deaf to avoid conversation. Several times they were stopped by authorities who demanded to see Ellen’s proof of ownership of William, and each time, someone intervened. At one point, a woman in Virginia accosted them, insisting that William was her runaway slave.

It wasn’t until they reached Philadelphia that they dared reveal their identities. There, Northern abolitionists helped them find a place to stay. Several years later, they found themselves still being pursued by slave hunters; the pair moved to England until the 1870s, when they went back to Georgia and established a school.

9William Wells Brown

William Wells Brown was born in Kentucky in 1814, the son of a slave and an unnamed white relative of his mother’s master. He and his mother traveled with the family, and in 1832, they tried—and failed—to escape. Afterward, he was sold and put to work on riverboats, where he quickly learned all he would need to know to escape for good. And escape he did. In 1834, he made his way to Cleveland, where he started his career as an abolitionist, lecturer, and writer. He settled in Buffalo, New York for a while, but eventually moved on to England after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was established. It was there that he wrote the first novel credited to an African-American author.

The book, Clotel, tells the story of one of Thomas Jefferson’s children, born from his slave mistress, and of her attempts to find happiness in the face of hate, prejudice, and the ever-present threat of slavery. She even gets a taste of that happiness, secretly marrying a wealthy plantation owner and bearing his daughter; the happiness is short-lived, though, and only lasts until he leaves her for a white woman and she is sold back into slavery.

Later, after moving back to Boston, Brown went on to write what’s considered the first play by an African-American playwright, The Escape; Or, A Leap For Freedom. Published in 1858, the work is a sweeping social commentary on the conflict between the pre–Civil War North and South and, on a smaller scale, it’s also the story of two slaves married in secret.

8Priscilla’s Homecoming

Family records and documents dating back to the beginning of the slave trade are rare enough, and an unbroken chain of documents telling the complete story of a single person’s family is even more rare. That’s what makes Priscilla and her ancestors so unique. On April 9, 1756, a ship called the Hare left Sierra Leone bound for America. On board were captives, and those fortunate enough to survive the trip had a lifetime of slavery waiting for them. Among those captives was a 10-year-old girl who was given the name Priscilla when she was sold to the owner of a South Carolina rice plantation.

Priscilla spent her entire life on the plantation and gave birth to 10 children. The lives of some of those children were documented as well, in what would eventually be assembled to become an unbroken, 250-year chain of documents leading to her great-great-great-great-great-granddaughter, Thomalind Martin Polite. Since finding out the history of her family, Polite has returned to Sierra Leone as an ambassador to the home that her ancestor was forced to leave behind so many generations ago.

In addition to undertaking what she called a spiritual journey, Priscilla’s records are also shedding light on an often-overlooked part of the slave trade—the part that Northern ships had to play. The Hare, the ship that brought Priscilla to America, was based out of Newport, Rhode Island. In fact, the Northern state was one of the most prolific ports when it came to the transport of captives who had been taken from their homes in Africa and brought to America. While it’s easy to look at the issue of slavery in America as having a strict North-South division, the existence of Priscilla’s records has resulted in the penning of another chapter in the slave trade.

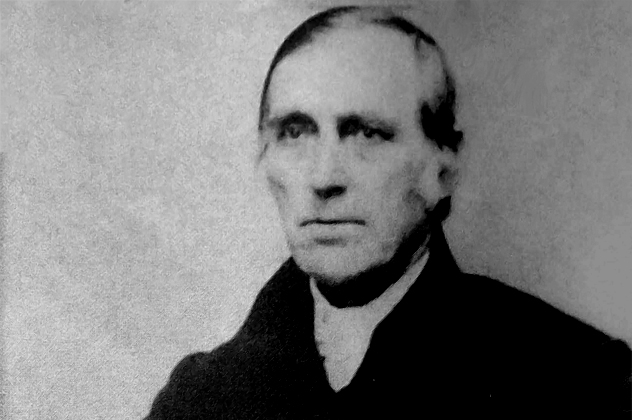

7Levi And Catharine Coffin

The Coffins were devoutly religious Quakers from North Carolina who, fortunately for thousands of people fleeing slavery, believed that the laws of man were null and void when they directly opposed the morals and values of their God. Not agreeing with the laws of man and actively opposing them are two entirely different things, and the Coffins were of the “actively opposing” viewpoint. Levi Coffin’s strong anti-slavery opinions were formed young, when he and his father witnessed a group of chained men on their way to a slave market. He questioned one of the men and was told that they had been taken from their families and that the road before them was a bleak one indeed.

At 15 years old, Coffin helped a boy his own age escape slavery, arranging for safe passage to freedom with friends of the family. As an adult, Coffin never forgot the encounter, and after he moved to Newport, Indiana, he set up his eight-room house as a safe stop on the Underground Railroad. He used his position as the executive director of State Bank’s Richmond office to fund his humanitarian activities, giving those who stayed a night at his home a hot meal and fresh clothes in addition to shelter and safety. Thousands of people passed through the safe haven of their home. By 1864, he had gone abroad to organize the English Freedmen’s Aid Society, which supplied money and aid to those in need back in America.

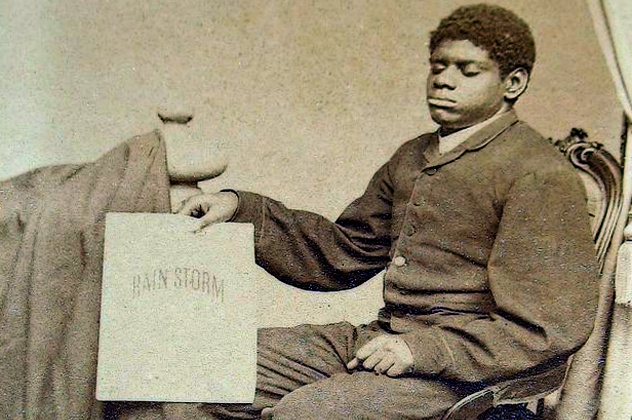

6Blind Tom

When Tom was born on a Georgia plantation, his owner deemed him useless and not worth the effort—or expense—of feeding once he realized that the baby boy was blind. Tom, his mother, and two other children were soon sold to a Columbus lawyer named General James Bethune. Once he was exposed to the piano and the musical leanings of the Bethune children, Tom began to show an amazingly innate musical talent. He could mimic all sorts of sounds, both musical and non-musical, and he could play back entire pieces of music after hearing them once.

The family that had bought him suddenly saw him as a gold mine rather than a useless mouth to feed, and they began sending him on tours throughout both the North and the South, well into the Civil War. Proceeds from his performances went to the Confederate army, and much of the money was used to care for the injured.

Unfortunately, Blind Tom also suffered from another, undiagnosed disorder (in retrospect, many people believe he was autistic). His lack of maturity and emotional growth meant that even after the Civil War, he still needed a guardian to manage his performances, tours, and finances; when he died in 1908, he still lived in the Hoboken home of Eliza Bethune. Sometimes called “the last slave,” Blind Tom’s ability to touch people through his music was undeniable. He played for President James Buchanan at the White House at a time when it was unheard of for any slave to use anything but the back door. Mark Twain wrote of his abilities, going to performance after performance. And when he was 15, Tom composed what would be his most famous piece—“The Battle of Manassas.”

5Gordon

Not much is known about the man simply known as Gordon, but according to the few accounts that have survived, he was bedridden for several months after receiving a severe beating from the overseer on the plantation where he worked as a slave. During his time recuperating, he made plans to escape. In 1863, not long after receiving the beating that would make the slave’s plight real for so many, he fled his captors and successfully evaded the bloodhounds by rubbing himself with onions. For Gordon, safety was enlisting in the Union army. It was during a medical exam that his scars were uncovered by doctors, who documented his condition in a photograph that would be seen around the world. Copies of the photograph were widely distributed, and suddenly, those who had never seen the brutality suffered by those who lived a life of slavery saw what people had to endure.

The photograph was distributed throughout the Northern states and even in Europe, along with a letter from the doctor who examined him. He called Gordon “intelligent and well-behaved.” Knowing that the photograph would elicit an emotion that words never could, he let it speak for itself. And speak for itself it did. Gordon became a symbol of triumph, of strength of spirit, and of bravery. Unfortunately, much of what happened to Gordon after he enlisted has been lost. The last record of his actions is a reference to his service at the siege of Port Hudson, but the effect of that single photograph has been immeasurable.

4Harriet Jacobs

Harriet Jacobs was born into slavery in 1813, but her early childhood was a happy one. Her mistresses taught her how to read and sew and nurtured her in what was by all accounts a loving family. When she was a teenager, her mistress passed away and gave her to the service of her niece. Because the niece was only a toddler at the time, Harriet became the property of the girl’s father, Dr. James Norcom.

Norcom became obsessed with the teenage girl, who suddenly found herself the target of a sexual predator and his jealous wife. She took shelter in a relationship with a nearby attorney, having two children with him. Those children by law belonged to Norcom, and in an attempt to anger Norcom into selling her children (to their waiting father), Jacobs made him think that she had escaped. In reality, she was hiding in the crawlspace above the home, where she could watch her children.

Harriet spent seven years hiding, until her children were sold into the custody of their father and taken to Washington, DC. Once they were out of Norcom’s reach, she escaped and headed to New York. Eventually, she met up with her children in New York, where she was still pursued by Norcom. It was while she was living in New York that she started writing, first in the form of letters and finally penning a book that touched on a subject that was sadly overlooked even by abolitionists: the sexual abuse suffered by female slaves. Her book, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, was written under the name Linda Brent. Names were changed, but her mission was accomplished.

Suddenly, abolitionists in the North saw the truth of what many female slaves had to endure. Eventually, Jacobs returned to the Washington, DC area where she worked with refugee slaves who had been displaced by the war.

3George Liele

George Liele was born into a deeply religious Virginia family around 1750. Separated from his biological family early, Liele was sold to a Baptist deacon who allowed Liele to go to church with the rest of the family. It was after they moved to Georgia that he knew he had found a calling. Liele began preaching to other slaves who weren’t able to read the Bible for themselves, and Liele was eventually ordained and licensed to preach by the same church that he had first attended with his owners. Liele went on to preach throughout Georgia before going on to establish his own church in Kingston, Jamaica.

He converted several hundred people and eventually established a school as well. His parish consisted of both free men and slaves, and he faced his share of conflict even though he did his best to avoid problems. Soon, one of his converts, a man named Moses Hall, opened a church of his own and garnered the wrath of slave owners. They stormed the church and beheaded David, one of Moses’s assistants, as a warning, then threw Moses on the ground before the severed head. They asked him if he knew why they had done it, and Moses answered, “For praying.” “From this time let us have no more of your prayer meetings,” they replied, “for if we catch you at it we shall serve you as we have served David.”

Without hesitation, Moses knelt on the ground, clasped his hands together, and said, “Let us pray.” The other slaves gathered around, and the flummoxed slave owners left without touching them again. Liele himself continued founding other churches throughout Jamaica and has since been credited with starting the first African-American churches in the United States.

2Polly Berry And Lucy Delaney

Polly Berry was born a free woman in the early 1800s in Illinois. As a child, she was kidnapped by slave-catchers and sold to a Southern general. Polly had two daughters named Lucy and Nancy with another slave. With their owner’s death, the girls were sent even farther south and farther away from freedom. Nancy was the first to escape, making her way into Canada. Polly soon followed, returning to her home in Illinois. It was there that she took her case to the courts, suing her owners for her freedom on the grounds that she had been born free and kidnapped into slavery. Because she was able to prove that she had been born free, the courts awarded her continued freedom.

After Polly won the case, she went back to the courts to free her daughter, Lucy. In 1842, Lucy escaped her masters, who were threatening to sell her. She fled to her mother and was held in jail as Polly fought in court to have her daughter officially freed. As the daughter of a free woman, there was no legal grounds for Lucy to be enslaved. Lucy spent 17 months in jail, but was eventually freed at the end of the court case. She was 14 years old. Lucy later married a man named Frederick Turner, who was killed in a steamboat explosion while working. The steamboat had been named for the attorney who had argued for Lucy’s freedom, Edward Bates. Lucy later went on to write their story in the narrative From the Darkness Cometh the Light, or, Struggles for Freedom.

1Elizabeth Keckley

Elizabeth Keckley was born into the life of a slave, but through strength, bravery, and more than a little business savvy, she would become a highly sought after dressmaker in the nation’s capital as well as a friend and confidante of the First Lady. Born in Virginia in 1818, one of the earliest recorded events in her life was a sexual assault by a man who would become the father of her son, George. In 1852, she married a man who had told her that he was free. He was a slave, however, and Keckley’s plans to purchase her freedom and her son’s freedom fell through because of the added strain of supporting a husband.

Already running her own dressmaking business, several of her clients gave her the money she needed to buy their freedom; she did, then took herself and her son to Washington, DC, left her husband behind, and set up another dressmaking business. Keckley’s skill as a seamstress soon became well-known, and she had clients like the wives of Jefferson Davis and Stephen Douglas. In 1861, she was recommended to Mary Todd Lincoln. The First Lady not only admired her skills as a seamstress, but the two soon became close friends. They helped each other through the loss of their sons, and Keckley was soon traveling with Lincoln throughout the Civil War. After Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, Mary Lincoln found herself impoverished and facing scandal. Keckley closed her business in Washington and moved to New York City to help her, organizing her estate and even raising money to help support her friend, causing a massive scandal as she did so.

Keckley also wrote her autobiography, Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House, in order to raise more money to help the ailing widow. Mary Lincoln refused much of the money that Keckley raised for her, and in the end, it was the autobiography that drove them apart. Keckley had a writer helping her, and she turned over personal letters and documents with a promise that personal, potentially embarrassing entries would be omitted. The omissions never happened, which caused a rift that was never mended between the two women. Keckley eventually returned to Washington, DC, all but destitute. Now, her work is considered one of the few candid glimpses into the lives of the Lincolns.