Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

10 Ways Samurai Were Nothing Like You Thought

Samurai were more complicated than modern society’s image of a self-sacrificing warrior class. Though they were at times the honor-bound fighters of legend, they were also gold-hungry mercenaries, pirates, travelers, Christians, politicians, murders, and vagabonds.

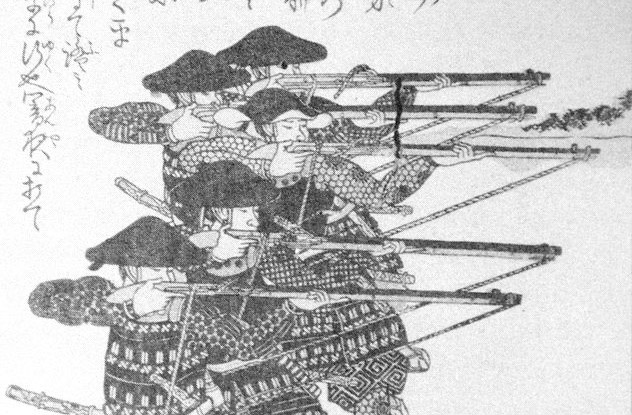

10Samurai Were Not So Elite

Though we think of the samurai as an elite fighting force, the majority of Japan’s army were foot soldiers called ashigaru, and it’s foot soldiers who win wars.

Ashigaru began as common rabble plucked from rice fields, but when daimyo realized a well-trained standing army was superior to on-and-off warriors, they trained them to fight. Ancient Japan had three kinds of warriors—samurai, ashigaru and ji-samurai. Ji-samurai were part-time samurai, working as farmers the rest of the year.

When ji-samurai took up the samurai business full-time, they joined the ashigaru rather than the ranks of their more affluent counterparts. Ji-samurai certainly weren’t as respected as true samurai, but their assimilation into the ashigaru was hardly a demotion. Japan’s ashigaru could be on near-equal terms with its samurai. In some areas, the two classes couldn’t even be distinguished.

Military service as an ashigaru was the one avenue to climb feudal Japan’s social ladder, culminating when Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the son of an ashigaru, rose to become the preeminent ruler of Japan. He then kicked the ladder out from under anyone who wasn’t already a samurai by freezing Japan’s social classes.

Rediscover the facts and legends surrounding Japan’s most ancient and feared warriors! Buy Samurai: An Illustrated History at Amazon.com!

9Christian Samurai

The arrival of Jesuit missionaries in southern Japan led some daimyo to convert to Christianity. Their conversion was perhaps more practical than it was religious, since ties to Christendom meant benefiting from European military technology. Christian daimyo Arima Harunobu put European cannons to use against his enemies at the battle of Okita-Nawate. Since Harunobu was a Christian, a Jesuit missionary was present for the battle and recorded his samurai—rather misguidedly—kneeling and reciting the Lord’s Prayer before each time they fired their prized cannons.

Being a Christian stopped daimyo Dom Justo Takayama from acting as any other samurai warlord during his reign. When Japan expelled Christian missionaries and forced Japanese Christians to apostatize, Takayama chose to flee Japan with 300 other Christians rather than renounce his faith. Takayama is currently in consideration for Catholic sainthood.

8Head-Viewing Ceremonies

An enemy’s head was proof of a samurai’s duty done. After a battle, heads were collected from their owners and presented to the daimyo, who enjoyed a relaxing head-viewing ceremony to celebrate his victory. Heads were washed thoroughly and had their hair combed and teeth blackened, which was a sign of gentry. Each head was then set on a small wooden holder and labeled with the victim’s and killer’s names. If there was no time, a hasty ceremony could be arranged over leaves to soak up the blood.

In one case, viewing conquered heads caused a daimyo to lose his own. After taking two of Oda Nobunaga’s forts, daimyo Imagawa Yoshimoto halted his march for a head-viewing ceremony and musical performance. Unfortunately for Yoshimoto, the rest of Nobunaga’s forces advanced for a surprise attack as the heads were being prepared. Nobunaga’s forces crept right up to Yoshimoto’s and attacked after a chance thunderstorm. Yoshimoto’s severed head then became the centerpiece for the head-viewing ceremony of his enemy.

A head-based reward system was open for exploitation. Some samurai would say the head of a foot soldier was a great hero and hope no one would know the difference. After actually taking a valuable head, some would abandon the battle with their money already made. Things got so bad that daimyos sometimes even prohibited taking heads so their men would focus on victory instead of getting paid.

7They Retreated From Battle

Many samurai were eager to fight to the death rather than face dishonor. Daimyo, however, knew that good military tactics included retreat. Tactical and true retreats were just as common in ancient Japan as anywhere else, especially when the daimyo was in danger. Aside from being one of the first samurai clans to use firearms, the Shimazu clan of south Japan was famous for its use of decoy forces pushing a false retreat to lure their enemies into a vulnerable position.

When retreating, samurai used a billowing cape called a horo, which deflected arrows while fleeing on horseback. The horo inflated like a balloon, and its protective insulation guarded the horse as well. Dropping the horse was easier than aiming for its rider, who could be quickly killed once pinned under his animal.

6Samurai Were Fabulous

In the early days, samurai delivered sprawling speeches chronicling combatants’ genealogies prior to one-on-one battles. Later, the Mongol invasions and incorporation of lower classes into warfare made proclaiming a samurai’s lineage in combat impractical. Wanting to maintain their strut, some warriors began wearing flags on their back that detailed their pedigree. However, since opponents likely weren’t interested in reading family histories in the heat of battle, the practice never caught on.

During the 16th century, warriors adopted sashimono, smaller patterns worn on a samurai’s back to display their identity. Samurai went to great lengths to set themselves apart, and sashimono were not just limited to flags but also objects like fans and wooden sunbursts. Many went further and marked their identity with elaborate helmets set with antlers, buffalo horns, peacock feathers—anything to attract a worthy opponent whose defeat would earn them honor and wealth.

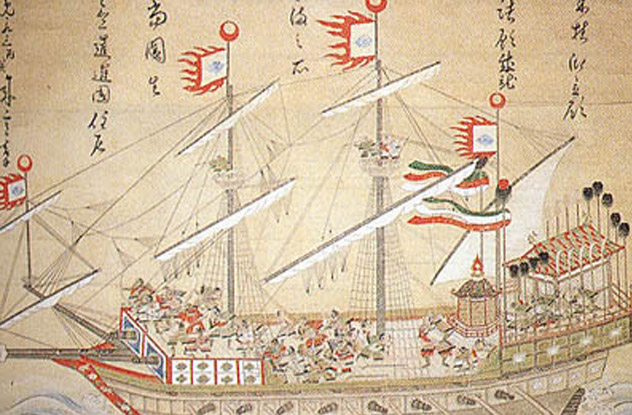

5Samurai Pirates

Near the beginning of the 13th century, a Mongol invasion pulled the Korean army away from its coast. A bad harvest had also left Japan with little food, and with its capital far to the east, unemployed ronin in the west suddenly found themselves in need of revenue and with little supervision. All this kicked off an age of Asian piracy whose chief players were samurai.

Called wokou, the pirates wrought so much havoc that they were responsible for many international disputes between China, Korea, and Japan. Though wokou included an increasing number of other nationalities as time passed, early raids were carried out primarily by the Japanese and continued on and off for years with the pirates under the protection of local samurai families.

Korea eventually came under Mongol control. With the wokou enemy now Kublai Khan, who was told by Korean envoys that the Japanese were “cruel and bloodthirsty,” the Mongols began an invasion of Japanese shores.

The invasion failed, yet it helped discouraged further wokou raids until the 14th century. By that time, the wokou were a mixed bunch from several parts of Asia. But since they carried out their numerous invasions of Korea and China from Japanese islands, the Ming emperor threatened to invade Japan unless it managed its pirate problem.

4Seppuku Was Actively Discouraged

Seppuku, or ritual suicide, was a samurai’s way to preserve his honor in the face of certain defeat. Everyone was after his head anyway, and he didn’t have much to lose except his nerve in the face of spilling his own guts over the floor. But while samurai were eager to end their lives honorably, daimyo were more concerned with maintaining their armies. The more famous historical examples of mass suicide overshadow the simple truth that it just didn’t make sense to waste good talent. Victorious daimyo often wanted defeated enemies to pledge them their allegiance instead of committing seppuku.

One type of seppuku, called junshi, had a samurai following his dead lord into the afterlife. That proved problematic for the lord’s heir. Instead of inheriting his father’s samurai army, he ended up with a front yard full of the corpses of his best men. And with the new daimyo honor-bound to support the family of a dead samurai, it was also an unattractive financial prospect. Junshi was eventually condemned by the Tokugawa shogunate, though that didn’t stop men from following it.

Defeat your enemies with honor with a Full Tang High Carbon Steel Katana! Only $52.95 at Amazon.com!

3Samurai Abroad

While employed samurai rarely left their daimyo’s territory except to invade another’s, many ronin found fortune abroad. Among the first foreign nations to employ samurai was Spain. In a plot to conquer China for Christendom, Spanish leaders in the Philippines added thousands of samurai to a multinational invasion force. The invasion never got off the ground for lack of support from the Spanish crown, but other samurai mercenaries were often employed under the Spanish flag.

Samurai of fortune especially distinguished themselves in ancient Thailand, where a Japanese settlement of about 1,500 aided in military campaigns. The colony consisted mainly of ronin seeking fortune abroad and Christians fleeing the shogunate. Leader Yamada Nagamasa’s military support of the Thai king won him both a princess and a noble title. Nagamasa was given lordship over a piece of southern Thailand, but after choosing the wrong side in a war of succession, he died of his wounds in battle. After his death, the Japanese presence in Thailand quickly diminished, many having fled to nearby Cambodia since the new king was anti-Japanese.

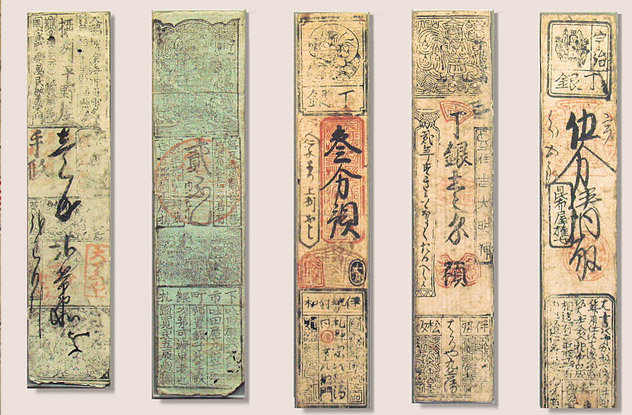

2Later Samurai Were Poor And Could Murder Peasants

After Japan was unified, samurai who had been making a living off their country’s endless civil wars found themselves with nothing to fight. No war meant no heads. No heads meant no money, and the lucky few of Japan’s thousands of samurai who kept their jobs were now working for daimyo who were paying them in rice.

By law, samurai were forbidden from supporting themselves. Commerce and farming were deemed peasant work, which made samurai’s only income a fixed rice stipend in a rapidly monetizing economy. A handful of rice didn’t buy as much sake as it once had, so samurai had to trade in their rice for real currency. Unfortunately for the hard-pressed upper class, giving nice gifts, having nice things, and wearing stylish clothes was part of a samurai’s job description. So the Edo period saw many samurai falling into a black hole of debt with lenders.

This might be why they were given the right of kirisute gomen, the legal right to kill insolent commoners. It would have been tempting for the beggared samurai to cancel his debts by way of the sword. But there are almost no documented cases, so it seems samurai at large didn’t exploit this right.

1How It All Ended

For roughly the last 250 years of their existence, samurai were slowly turning into poets, scholars, and bureaucrats. The Hagakure, possibly the greatest book about how to be a samurai, was the commentaries of a samurai who lived and died without participating a single war.

Still, samurai remained Japan’s warrior class, and despite the prevailing peace, some of Japan’s best swordsmen came from the Edo period. Those samurai who didn’t trade their katana for a pen trained diligently in swordsmanship, fighting duels to win fame enough to open their own fighting schools. The most famous book about Japanese warfare, The Book of Five Rings, came from this period. Author Miyamoto Musashi was considered one of Japan’s greatest swordsmen, participating in two of the period’s few major battles as well as numerous duels.

Meanwhile, those samurai who had stepped into the political arena had been steadily growing in power. Eventually, they grew strong enough to challenge the shogunate. They succeeded in toppling it, fighting in the name of the emperor. Having overthrown Japan’s government and installed the emperor as a figurehead, they had effectively seized control of Japan.

The move, along with numerous other factors, had brought about the start of Japan’s modernization. Unfortunately for the remaining samurai, modernization included a Western-style conscript army that drastically weakened the warrior class.

The growing samurai frustrations finally culminated in the Satsuma Rebellion very loosely depicted in The Last Samurai. Though the real rebellion looked very different from how it was portrayed by Hollywood, it could be argued that samurai, true to their warrior spirit, went out in a blaze of glory.

Nathan keeps a Japan blog where he writes about the sights, expat life, and finds Japanese culture in everyday items. You can also find him on Facebook and Twitter.