Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

10 Myths About Famous Explorers

Explorers have probably been more romanticized than any other group in history. There’s something about the idea of embarking into the unknown, going where no man has gone before, that makes us believe that anything is possible. Of course, along with that come a lot of romantic stories that just aren’t true at all. For example . . .

10Robert Peary Was The First Man To Reach The North Pole

The Truth: Not even in his own account was Peary the first man to the pole. That was actually the other member of his expedition, Matthew Henson. However, Henson was black, so while Peary was widely celebrated, Henson sank into obscurity and had to get a job in customs to get by. Peary refused to answer Henson’s letters, help him get a job, or return the photos of the expedition that Henson had taken and paid for. Henson would later conclude that Peary was jealous he reached the pole first.

However, even Henson probably wasn’t the first. Just before Peary and Henson returned, an explorer named Frederick Cook announced he had reached the pole. Unfortunately, Cook had left the instruments that would prove his claim with another member of his party while he rushed back with the news. The ship that was supposed to retrieve them vanished, and Cook’s assistant had to be rescued . . . by Peary, who demanded that Cook’s instruments be abandoned. Then he browbeat Cook’s Inuit employees—who could not speak English—into signing documents saying they hadn’t reached the pole. When he returned to America, Peary’s powerful backers launched a smear campaign against Cook. Without the instruments it’s impossible to be sure, but subsequent explorers have found that Cook’s description of his route matches the landscape perfectly, including things he would have no way of knowing had he been a fraud.

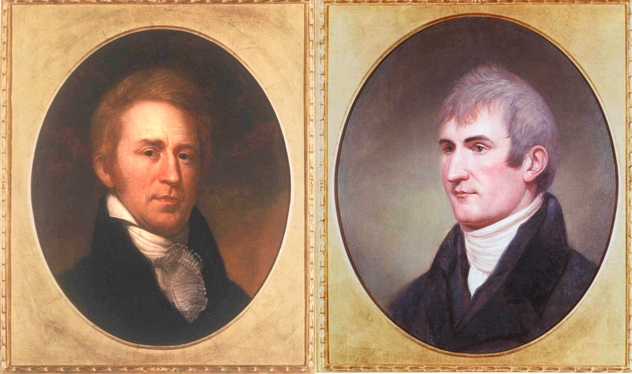

9The Lewis And Clark Expedition Was A Huge Success

The Truth: Lewis and Clark failed to achieve any of their aims and immediately sank into obscurity—until the 20th century rolled around, most Americans would not have heard of them. They signally failed at their actual goal—finding a water route to the Pacific—and a disappointed Thomas Jefferson never boasted of the expedition he had launched. They also didn’t pioneer any routes to the West, since the path they took was literally one of the worst ways you could cross the continent, and subsequent settlers never followed it.

Lewis also failed at his plan to write an account of their journey that would inspire others to go west. Instead, he developed a bad case of writer’s block and shot himself in the head with only a few words written (many of which were descriptive passages plagiarized from explorers of different places). The book was eventually hurriedly ghostwritten and failed to sell. The genuinely amazing botanical and scientific information Lewis and Clark had collected was not included and was not published for decades, by which time the information had largely been discovered independently.

In part, the expedition was saved by Sacagawea. In 1902, the proto-feminist Eva Emery Dye was looking for a strong female hero when she stumbled upon Sacagawea. Dye’s novel became a bestseller, and Sacagawea’s newfound popularity with the suffragette movement did much to drag Lewis and Clark out of obscurity.

8Ponce De Leon Was Searching For The Fountain Of Youth

The Truth: He wasn’t. None of de Leon’s writings or letters, or the writings of anyone else associated with his expedition, mention the Fountain of Youth. The truth is that de Leon was a traditional Spanish conquistador—he was out for gold, land, and riches—and wasn’t afraid to brutally massacre the Native American inhabitants of the areas he colonized. As the first governor of Puerto Rico and later in Florida, de Leon demonstrated a ruthlessly pragmatic nature at odds with later stories of his search for a mythical spring.

In fact, the story was made up by Ponce’s enemies in Spain after his death in order to make him look like a gullible, sexually impotent idiot. It worked—the story largely eclipsed his actual achievements, like discovering the Gulf Stream. The myth gained traction when America acquired Florida and writers like Washington Irving discovered that they were much more comfortable with the idea of Ponce as a hapless, Don Quixote–like figure, rather than the reality of a brutal man whose name was a source of terror for the native inhabitants of the area. Centuries later, a 16th-century smear campaign is still repeated as fact in some American textbooks.

7The Aztecs Thought Cortes Was The God Quetzalcoatl

The Truth: If they did, everyone involved kept very quiet about it. Cortes himself never even mentions Quetzalcoatl or being mistaken for a god in any of his (wildly popular) writings. There isn’t even any actual evidence that the Aztecs believed in Quetzalcoatl as a messiah who would one day return from the east—the earliest references to the myth come from long after the conquest, when indigenous religions were well on their way to being supplanted by Christianity. Later in the 16th century, Spain’s own Royal Chronicler Fernandez de Oviedo, himself a veteran of the conquest of the West Indies, firmly stated the story to be untrue.

The earliest evidence for the story comes from a book by Franciscan Catholic missionaries, written decades after Cortes’s death. The book contains several speeches, supposedly given by Montezuma, which are conveniently full of Christian imagery and fairly clearly place the Spanish conquest as part of a divine plan to Christianize the Americas—a remarkably convenient turn of events for a religious order seeking to do just that.

6Columbus Died In Poverty

The Truth: This myth makes a great story—the man who changed the world perhaps more than any other dying alone and unappreciated. Plus, it’s very comforting for those with an (accurate) view of Columbus as a genocidal monster whose cruelty disgusted even his contemporaries. But the truth is that Columbus died an extremely wealthy aristocrat. Converting currency across the ages is a tricky business, but the revenue from his estates on Hispaniola, as well as his rewards from the Spanish government, would certainly have made him a millionaire in today’s money.

The myth probably comes from Columbus’s own bitterness at not getting the insane 10 percent of all gold and silver from the Americas he believed he was entitled to. He spent the last years of his life compiling documents related to this claim, which his descendants used in a famous series of lawsuits against the crown. The myth was subsequently popularized by Washington Irving. While it is true that Columbus was removed as governor of Hispaniola, that has more to do with his appalling record as an administrator than any conspiracy to screw him over.

5Charles Lindbergh Was The First Man To Fly Across The Atlantic

The Truth: An astonishing 84 people had flown across the Atlantic before Lindbergh. The earliest transatlantic flight was made by Lieutenant Commander Albert Read of the US Navy and his crew, who flew from Newfoundland to the Azores and then on to Portugal in 1919—a full eight years before Lindbergh’s own flight. Lindbergh wasn’t the first to fly nonstop either—that was John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown of the Royal Air Force, who flew just a month after Read did. They received a £10,000 prize from the Daily Mail for their trouble. The first people to fly nonstop between Europe and New York were George Scott of the RAF, his crew, and a stowaway former boxer named William Ballantyne.

Lindbergh was the first man to fly solo across the Atlantic, as well as the first person to fly from the US to continental Europe (rather than Britain). It was a phenomenal achievement, and he is worthy of recognition for it. But why is Lindbergh a household name when Read and Alcock and Brown are not? Well, Lindbergh’s crossing had drama going for it—he was racing to win a huge cash prize for the first man to fly between New York and Paris and beat out several better-known aviators to claim the cash. Lindbergh and his backers were among the first to assiduously court the media—within a few months of his flight there was more newsreel footage of him than any other human being in history. When he returned to New York, an estimated four million people came out to line the parade route. His spectacular fame meant that Lindbergh quickly came to overshadow all other aviators, before or since.

4Ernest Shackleton Recruited His Crew By A Newspaper Ad

The Truth: This might not be the best-known myth on the list, but it’s certainly among the most romantic and persistent, appearing in multiple biographies of Shackleton, as well as the acclaimed Kenneth Branagh miniseries of his life. According to the myth, the legendary Arctic explorer Ernest Shackleton recruited the crew for his famously disastrous but ultimately triumphant Antarctic expedition by means of an advertisement in the Times newspaper. Short and to the point, the ad in its entirety supposedly read: “Men wanted for hazardous journey, small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful, honor and recognition in case of success.” According to the myth, 5,000 men replied seeking a place.

It’s a fantastic story, confirming all our admiration for the bold men of the age of Antarctic exploration and their stiff-upper-lip nature. Unfortunately, it just doesn’t seem to be true at all. Even though historians have trawled through every copy of the Times from Shackleton’s lifetime—as well as other newspapers, exploration magazines, and the archives of the Geographical Journal—nobody has ever been able to find a copy of the ad (there’s a $100 reward, on the off-chance you happen to be sitting on one). Shackleton wouldn’t have needed an ad anyway—his expedition generated a huge amount of press and there was no shortage of applicants. But don’t give up your romantic image of Shackleton’s crew just yet. One member, Frank Worsley, got the job after accidentally stumbling across Shackleton’s office and deciding to apply on a whim.

3Erik The Red Gave Greenland A Misleading Name To Attract Settlers

The Truth: It’s true that Greenland was discovered by an exiled Icelandic murderer known as Erik the Red (other Norsemen may have reached the country before Erik, but he was almost certainly the one to name it and encourage permanent settlement). And it’s quite possibly true that Erik gave it the attractive name of “Greenland” in order to entice settlers—that’s just common sense. However, that doesn’t mean that Erik was engaging in some sort of real-estate scam—contrary to our current picture of the island, in Erik’s time, Greenland was, well, a green land.

In the 10th century, during Erik’s lifetime, Greenland was going through a relatively temperate period. When the ship beached itself in one of the country’s fjords, Erik would have found a rich green pasture, actually more fertile than the rocky, overgrazed land of his native Iceland. When Erik named the country “Greenland,” he was just being honest—the rich glacial valleys were a paradise compared to many other areas of Scandinavian settlement. It wouldn’t last of course—the Little Ice Age that began in the 14th century would spell death for the Vikings of Greenland, who lost contact with their brethren in Iceland and mysteriously disappeared, either the victims of famine or conflict with the newly arrived Inuit groups who were better suited to survival in the icy new conditions.

2Magellan Was The First Person To Circumnavigate The Globe

The Truth: Magellan never circumnavigated the globe, although he came tantalizingly close before being killed in a disastrous encounter with natives in the Philippines. Since Magellan had previously been as far east as what is now Malaysia, he came within a relatively short distance of becoming the first man to have traveled all the way around the world. Of his initial crew of 237, just 18 survived to make it all the way back to Spain under the leadership of Juan Sebastian Elcano.

However, even they probably weren’t the first. On his previous visit to Malaysia, Magellan had acquired a local slave known as Enrique, who went on Magellan’s subsequent voyage and deserted after his death. Since Enrique was recorded as speaking the local dialect in the Philippines, some historians have speculated he was originally from there. Regardless, he certainly knew where he was, spoke the language, and would have been more than capable of negotiating passage throughout the region. If, as seems likely, he returned home after deserting, he would have been the first man to cross the entire globe.

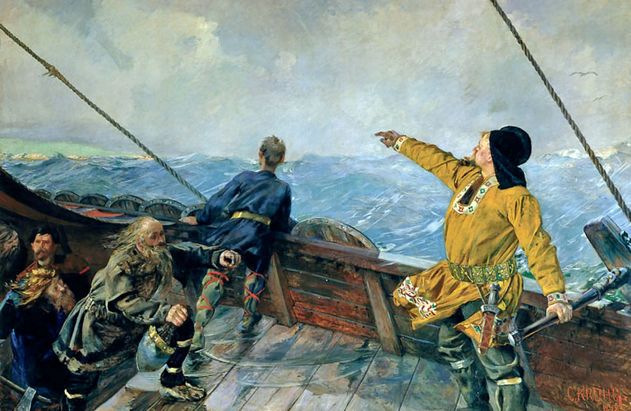

1Leif Erikson Was The First European To Discover America

The Truth: Erik the Red’s less-murderous son, Leif Erikson, has often been hailed as the first European to discover the Americas. Being a chip off the old block, he gave the new land the attractive name “Vinland,” “because vines grow there of themselves and give the noblest wine.” The settlement he founded has recently been identified as L’Anse aux Meadows, in what is now Newfoundland. But contrary to what a number of history books would have you believe, Leif almost certainly wasn’t the first European to lay eyes on the misty shores of the New World.

That honor goes to another Norseman, Bjarni Herjolfsson. According to the Norse Greenlanders Saga, now recognized as the oldest and most reliable account of the Norsemen in North America, Bjarni was a ship’s captain and the son of a settler in Iceland who would usually spend every other winter staying with his parents. But one winter, Bjarni returned home to find that his parents had followed Erik the Red to Greenland. Apparently unable to take a hint and get his own place, Bjarni decided to follow them and spend the winter in Greenland.

After sailing west for days and becoming badly lost at sea, Bjarni came across a strange land. His crew suggested exploring further, but Bjarni realized that the thickly wooded coast didn’t resemble the descriptions of Greenland he had heard and decided to return the way they came, eventually finding his way back to his parents’ house. Despite his lack of curiosity, Bjarni and his crew were the first Europeans to lay eyes on the Americas—Leif would follow Bjarni’s route on his own journey to the New World.