Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

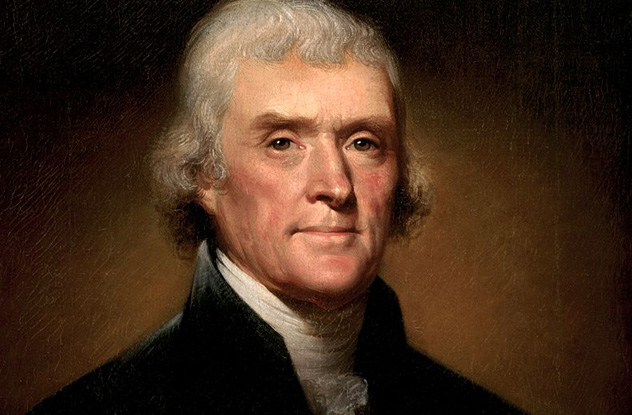

10 Stories That Show The Weird Side Of Thomas Jefferson

When it comes to America’s Founding Fathers, there’s no one more captivating or controversial than Thomas Jefferson. The third president of the United States, Jefferson was an extremely talented man who could play the violin, design his own furniture, and build his own mansion.

Jefferson was also something of a paradox. He was an aristocratic elitist who stood up for state’s rights, a strict constructionist who increased the power of the president, and a freedom-loving revolutionary who owned a whole lot of slaves.

10French Cuisine And Gorgeous Gardens

When most people think of Thomas Jefferson, they think of how he wrote the Declaration of Independence or purchased the territory of Louisiana. They don’t usually associate America’s third president with fine dining. And that’s too bad because Jefferson was a man who knew how to eat and eat well.

Described as “America’s original foodie,” Jefferson popularized French cuisine in 1784 when he apprenticed his slave, James Hemmings, to one of the best French chefs in the business. (It was actually a bargain. Jefferson said, “Cook for me, and I’ll eventually give you your freedom,” which he did.) Jefferson also introduced macaroni and cheese to the US, wrote the earliest known American recipe for vanilla ice cream, and lived on a nearly vegetarian diet, courtesy of his two-acre garden.

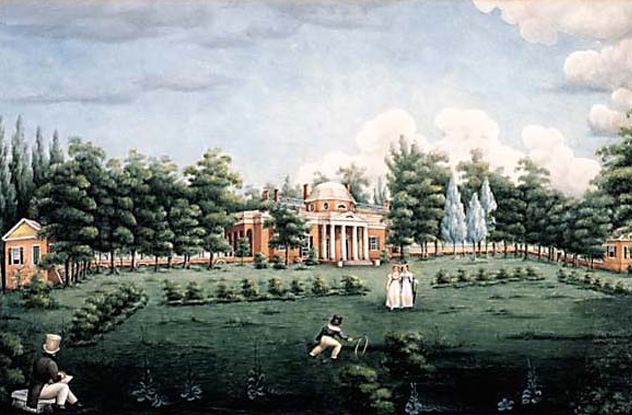

Jefferson’s garden was revolutionary for its day. The man grew all sorts of plants many Americans had never seen, and he recorded every little detail—every agricultural success and failure—in his voluminous notebooks. If you stroll across the Monticello lawn, you’ll find over 130 different kinds of fruit trees, including cherry, almond, and pomegranate. You’ll also spot 300 kinds of vegetables like sea kale, okra, Texas bird peppers, and Italian squash.

Jefferson would often challenge his neighbor George Divers (who was a much better farmer) to pea-growing competitions, and he even planted tomatoes, which was a big deal at the time because most everyone thought they were poisonous. You can imagine the shock when people learned Jefferson was serving such dangerous fruit at White House dinners. Yet the meals tasted so good that critics actually claimed Jefferson was using food to buy political influence.

9His Odd Opinions On Dogs

They say a dog is man’s best friend. If you asked Thomas Jefferson, he might agree, but then he might not. It all depends on when you asked.

Back in 1789, Jefferson had a favorable opinion toward canines, especially shepherd’s dogs. In fact, he believed they were the original dog breed. While historians aren’t exactly sure what these sheepdogs looked like, we know Jefferson went to extreme lengths to buy one. While in France, he walked for miles in the wind and rain and even stumbled across a suicide victim while searching for the perfect pet. According to Jefferson, it was worth the trouble because sheepdogs were “the most careful, intelligent dogs in the world.”

Eventually, Jefferson purchased a pregnant dog named Bergere and took her to Virginia where he planned on colonizing the New World with European animals (including creatures like nightingales, hares, and Angora goats). Jefferson was proud of his pets and bragged how they herded everything from sheep to chickens. Tales of the Monticello mutts spread fast, and friends wrote Jefferson letters, asking if they could have a dog too.

However, Jefferson was a strict disciplinarian. After buying a shepherd’s dog named Grizzle, he decided its descendants were too troublesome. So he killed them. Even worse, he ordered his foreman to execute all of his slaves’ dogs because he didn’t want them eating his sheep.

As Jefferson aged, his opinions on dogs radically shifted. In a letter dated 1811, he wrote, “I consider them [dogs] as the most afflicting of all the follies for which men tax themselves.” Jefferson felt “hostility” toward the animals, and claimed he “would readily join in any plan of exterminating the whole race.”

8Jefferson And Adams Were Shakespeare Nuts

Jefferson and John Adams had the biggest bromance of the 18th century. The two met in 1775, and after that, they were best buds for life. Sure, there was a nasty period where Jefferson called Adams a hermaphrodite, and Adams took a potshot at Jefferson’s family tree, but every relationship has its rough patches, right?

When the two weren’t bickering, they were working on the Declaration of Independence or hanging out in France. They were so in sync they even died on the same day (the Fourth of July, no less). And while they had different opinions on politics, both Jefferson and Adams agreed on one thing: Shakespeare was awesome.

A Shakespeare fanatic, Jefferson watched Macbeth and The Merchant of Venice in London, but he believed the best way to enjoy the Bard was by reading his plays, not watching them. Jefferson owned his own Shakespeare concordance and plenty of annotated plays, once declaring, “Shakespeare must be signaled out by one who wishes to learn the full powers of the English language.”

Adams was a fan too, and when the duo met up in England in 1786, they decided to drop by Shakespeare’s house. The two visited the Bard’s childhood home in Stratford-upon-Avon, but it’s hard to tell if they enjoyed their trip. In his diary, Jefferson complained a whole lot about travel expenses. But according to Abigail Adams, when Jefferson arrived at Shakespeare’s house, he kissed the ground in reverence.

The two also got a glimpse of Shakespeare’s chair. Supposedly, this was the actual chair Shakespeare used to sit in, and the two Americans cut off a slice as a souvenir. According to Adams, everybody took a piece home, but Jefferson was skeptical. If this really was Shakespeare’s chair, then “like the relics of the saints, it must miraculously reproduce itself.”

7The Incredibly Odd Execution Rumor

Despite his quiet demeanor, Thomas Jefferson had repeated brushes with assassination—character assassination. In 1792, he bankrolled newspapers that attacked Federalist-friendly George Washington. He also supported muckraking journalist James Callender, who specialized in taking down politicians like Alexander Hamilton and John Adams. But even though he’s famous for that line about refreshing the tree of liberty with the blood of tyrants, Jefferson wasn’t really a violent man. Unless you ask John Travolta.

In the 2001 crime thriller Swordfish, Travolta played a soul patch–sporting rogue named Gabriel Shear, and while the movie was a critical disaster, it introduced a bizarre bit of Thomas Jefferson trivia. Right before killing a rival, Travolta casually mentions that Thomas Jefferson once shot a man on the White House lawn for treason. Suddenly, people wanted to know the name of this mysterious traitor. And why had Jefferson pulled the trigger?

The execution story had been made up by whoever wrote the Swordfish screenplay. There’s no evidence that Thomas Jefferson ever killed anyone, let alone on the White House lawn.

Theoretically, Jefferson probably could’ve shot a man if he’d liked. He was an excellent shot. At 25, Jefferson won first place in a shooting competition, and he later claimed he could hit a squirrel from 25 meters (90 ft) with one of his prized Turkish pistols. The man enjoyed firearms so much that he claimed rambling through the forest with a gun was one of the very best forms of exercise. Just don’t sneak up on him while he’s walking.

6Mammoths, Sloths, And Extinction

What’s the state fossil of Virginia? If you guessed “Chesapecten jeffersonius,” an extinct scallop commonly found in Chesapeake Bay, congratulations! You’re a paleontology nerd, just like Thomas Jefferson. This solidified shellfish was named after the southern statesman because Jefferson was a colonial-era Alan Grant with some rather unique ideas about ancient animals.

Jefferson was a prehistoric private eye, and one of his biggest cases was the mystery of the Megalonyx. In 1796, miners discovered an enormous claw inside a West Virginia cave. Curious, Jefferson examined it and several other bones, and after much deliberation, he decided they belonged to a huge cat, a monster “three times as large as the lion.” Megalonyx jeffersoni was actually a giant sloth, but even though he was wrong, someone named it after him.

Jefferson was also obsessed with prehistoric pachyderm and once covered the White House floor with mastodon fossils so he could study them. Jefferson didn’t believe mammoths were creatures of the past. He was positive that there were still living specimens in the American West, and that’s one of the reasons he sent Lewis and Clark exploring. He wanted them to find a mammoth.

Jefferson didn’t believe in extinction. While he wasn’t exactly a churchgoing man—this is the man who made his own Bible by cutting out the parts he didn’t like—Jefferson did believe the world was created by a higher being. So in Jefferson’s opinion, if God was involved, then creation was divinely perfect. But if an entire species could just die out, well, creation wasn’t so perfect and that didn’t mesh with Jefferson’s beliefs.

Sadly, Jefferson was wrong about extinction, and Lewis and Clark never found a mammoth, but they did send him back a prairie dog.

5He Could’ve Been Executed

It was August 2, 1776, and the members of the Continental Congress were preparing to sign the Declaration of Independence. After leaving his impressive autograph, John Hancock turned to his 56 fellows and allegedly said, “We must be unanimous . . . we must all hang together.” Benjamin Franklin responded, “Yes, we must indeed all hang together, or most assuredly we shall hang separately.”

While the story might be a myth, the gist of the joke was all too real. Treason against the crown was punishable by death, and the British had already tried to arrest Hancock and Samuel Adams. So when Thomas Jefferson signed his name to the Declaration, he knew he was facing death.

Yet this wasn’t the last time Jefferson risked execution.

In the 1780s, Jefferson was traveling through the Piedmont region of Italy. He wanted to acquire some Italian rice and take it back to South Carolina, but it was illegal to take rice outside the country. The Italians didn’t feel like sharing their seeds with other nations, and if you were caught smuggling grain, the penalty was death.

But Jefferson didn’t care and made a deal with a “muleteer to run a couple of sacks across the Apennines to Genoa.” However, he wasn’t sure the muleteer would make it. So, when no one was looking, Jefferson stuffed his pockets full of rice and sneaked it out of the country. Yes—Thomas Jefferson was a smuggler.

The rice did pretty well.

4A Lousy Public Speaker

If you want to become president of the United States, you need to know how to give a speech. Getting in front of a camera and stirring up the nation are pretty much mandatory for this particular job. Even if you need a teleprompter or make up new words on the spot, you need to feel comfortable in front of a crowd. But that wasn’t always the case. Take Thomas Jefferson for instance. He absolutely hated public speaking.

Rich, intelligent, and standing around 188 centimeters (6’2″), Jefferson doesn’t seem like he’d be a shy guy, but the man was a wallflower. John Adams once said about Jefferson, “During the whole time I sat with him in Congress, I never heard him utter three sentences together.” Perhaps Jefferson was so silent because he was so modest. At first, he even insisted that Adams write the Declaration of Independence. Or perhaps he kept quiet because he was embarrassed of how he sounded. Some historians believe Jefferson had a high-pitched voice and often stuttered.

Whatever the reason, Jefferson was terrified of crowds, and that didn’t do a lot for his career as a lawyer. In fact, Jefferson sometimes got so nervous that he’d fake sickness to get out of giving a speech. Allegedly, Jefferson gave only two speeches during his entire presidency, both of them during his inauguration, but he was so quiet that newspapers had to print his words in advance so spectators could read along.

To get out of delivering his State of the Union addresses, Jefferson would write out a speech and have someone read it for him, a tradition that continued until Woodrow Wilson took office. Psychiatrists from Duke University claim that Jefferson suffered from social phobia, but whatever the cause, Jefferson was undoubtedly one of the quietest politicians to ever work in the White House.

3The Mammoth Cheese

John Leland was a bit of a misfit. He was a Baptist minister and a die-hard Democratic-Republican who lived in Massachusetts, a Federalist state that wasn’t exactly Baptist country. Perhaps that’s why Leland was a Jefferson fan.

While the newly elected president often criticized organized religion, Jefferson promoted religious tolerance and thought everyone should be treated equally despite their beliefs. Leland appreciated Jefferson’s stance on religious freedom, at least where Baptists were concerned, and he wanted to thank the president—by making him a humongous wheel of cheese.

In 1802, Leland asked the women of his congregation to make the biggest wheel of cheese possible, creating it without any milk from “Federalist cows,” of course. The ladies obliged and milked about 900 pro-Jefferson heifers. After they were done churning, they’d created a 550-kilogram (1,200 lb) monster, and written into the cheese were the words “Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God.”

When the cheese was ready, Leland carted the wheel to the White House and presented the cheesy beast to the president. Jefferson was pleased and gave the Baptists $200 for their hard work. Federalist papers made a big stink about it and dubbed the wheel “The Mammoth Cheese.” They were referencing Jefferson allocating government funds to research woolly mammoths, a move the Federalists opposed, and the newspapers meant the nickname as an insult. But everyone thought it was a great name, and soon everyone was using the word “mammoth” to describe really big things.

Two years later, the cheese inspired the US Navy to bake a mammoth-sized loaf of bread for the president. Jefferson brought the loaf into the Senate building where he and the Senators feasted on beef, bread, and alcohol. There’s debate whether or not the Mammoth Cheese made an appearance, but let’s hope not. The thing was two years old.

2His Murderous Nephews

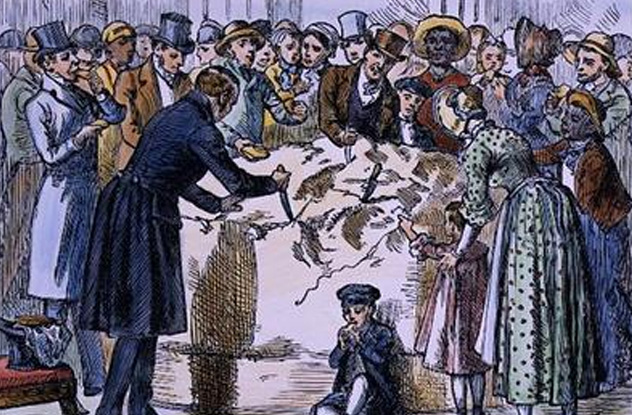

When it comes to slavery, Thomas Jefferson’s words didn’t always match up with his actions. We all know about his slave mistress, and we’ve read how he intentionally ripped families apart. But on the flip side, Jefferson condemned the institution in an early draft of the Declaration of Independence. These conflicting stories have led historians to debate whether Jefferson was a monstrous dictator or a benevolent master. But while Jefferson bought and sold human beings, at least he didn’t murder them.

His nephews, on the other hand, were a little more bloodthirsty. Lilburne and Isham Lewis were Kentucky farmers with financial difficulties and a fondness for alcohol. Whenever they started drinking, the two turned into monsters, and things got really bad on December 15, 1811.

Drunk and angry, Lilburne ordered a 17-year-old slave named George to fill a pitcher of water. George dropped the jar, and the brothers snapped. Lilburne and Isham dragged George into a plantation kitchen, chained him to the floor, and ordered their other slaves to build a fire.

Lilburne pulled out an axe and chopped off George’s head. The brothers then ordered the slaves to dismember the body and toss it in the fireplace.

The Lewises probably would’ve gotten away with their crime if an earthquake hadn’t struck the very next day. The tremors destroyed the fireplace, putting out the flames and saving some of the body parts. Two months later, somebody spotted a dog with George’s head in its mouth.

The brothers were arrested for murder, but after they skipped bail, the duo made a suicide pact. Things didn’t go as planned. The brothers intended to shoot each other, but before they could fire, Lilburne accidentally shot himself and quickly bled to death. Freaked out, Isham took off running, only to be arrested a second time for assisting a suicide. Isham never made it to trial; the sinister Houdini escaped once again.

No one knows what happened to Isham Lewis. Jefferson preferred not to talk about the scandalous affair.

1The Quest For A Giant Moose

Count Georges-Louis Leclerc Buffon was the curator of the King’s Natural History Cabinet in France and the author of the monumental science encyclopedia Historie Naturelle. When this man spoke, everyone listened. That’s why Thomas Jefferson was ticked off with Buffon’s theory of New World degeneration.

According to Buffon, North America was a marshy continent that had recently arisen from the waves. Thanks to all that moisture, New World wildlife was inferior to European plants and animals. They were smaller, more delicate, and spawned pathetic little runts. And the same thing applied to people. Buffon believed that Native Americans were stupid and lazy thanks to the humid atmosphere, and other scientists claimed that European immigrants would give birth to physical and intellectual weaklings.

The theory gained mainstream acceptance across Europe and was promoted in everything from textbooks to poetry. This didn’t sit well with US Ambassador to France Thomas Jefferson. He considered Buffon’s theory economically dangerous. Why would anyone want to move to the US if their kids would grow up as scrawny little wimps? Why would anyone want to trade with a country offering subpar goods? This was a serious matter, and Jefferson dedicated years to putting Buffon in his place.

Wanting to disprove Buffon’s theory, Jefferson started hunting for the biggest animals he could find, recording their size and weight in his book Notes on the State of Virginia. Even James Madison got into the act, sending Jefferson precise measurements of a Virginia weasel. Madison recorded everything from the color of the spleen to the “distance between the anus and vulva.”

But Jefferson did more than just write. He sent Buffon a cougar pelt and mastodon fossils, but the Frenchman wasn’t impressed. Then Jefferson proposed mailing Buffon a moose. The Parisian didn’t believe such a mighty creature could live in the soggy climes of North America, so if Jefferson could find a monster moose, Buffon would recant his theory.

Jefferson immediately wrote his friends for help, and the governor of New Hampshire knew a hunter who’d recently bagged a behemoth. The governor sent the moose to Jefferson, but the trip wasn’t exactly smooth. It took two weeks for 20 men to carry the cadaver through huge snow drifts, and the body started to rot. Even worse, the antlers disappeared. Thinking fast, the Governor included a few replacements—they belonged to a deer, an elk, and a caribou.

When the decomposed corpse showed up in 1787, Jefferson sent it straight to Buffon, telling him to picture it with more fur and bigger antlers. Surely now Buffon would rescind his theory and give the New World some respect. But before Buffon could publicly disavow his idea, the count died. Despite Jefferson’s best efforts, the theory lived on for 70 more years, sparking intense debate between Americans and Europeans, but nobody was ever as passionate about it as Jefferson.

If you want, you can friend/follow Nolan on Facebook, or you can send him an email.