Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

10 Of The Oldest Artifacts In The World

We humans have a special kind of awe for the oldest examples of the fruits of our creativity and intelligence. As we’ve discussed before, the artifacts we produce are a large part of what separates us from animals, and so we are justifiably proud of them. So when we can unearth an artifact and say this one is “the first,” or at least the oldest one we have, it has a deep significance.

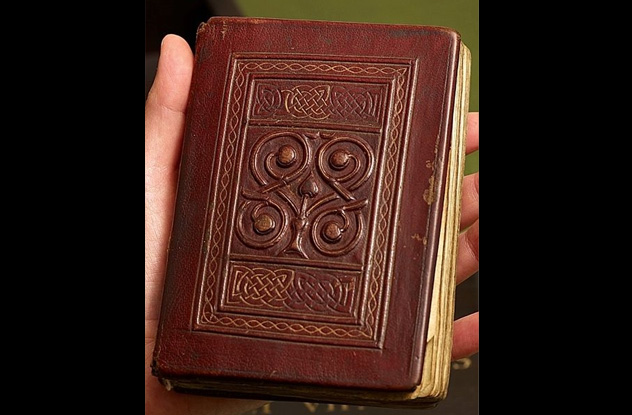

10The Oldest Intact European Book

What is the world’s oldest surviving book? Because the definition of a book has been debated since the very beginning of literature, that’s a hard question to answer and could easily encompass another whole article.

However, the oldest intact, European, bound book of the sort we are all used to reading nowadays is the St. Cuthbert Gospel (also known as the Stonyhurst Gospel or the St. Cuthbert Gospel of St. John). The red, leather-bound, and illuminated gospel book was written in Latin in the seventh century.

In 2012, the British Library in London paid an astounding $14 million to the Jesuit community in Belgium that owned the book, after the most successful fund-raising campaign in that nation’s history. A fully digitized version is now available online.

The book was a copy of the Gospel of St. John, originally produced in northeastern England for Saint Cuthbert and placed into his coffin over 1,300 years ago when he died. When Vikings began raiding the northeast coast of England, St. Cuthbert’s monastic community left their place on the island of Lindisfarne and took the coffin with them, preserving the book once they settled in Durham. The coffin was opened in 1104 when a new shrine was being built for the saint, and the book was discovered and preserved, changing hands until it passed on to the Jesuits.

9The Oldest Official Coin

Before state-issued coins, early coin-like badges were issued by wealthy merchants and influential members of society, some as trade items and others to denote station. While there is some debate, most experts agree that the world’s first true coin was the Lydian one-third stater, or trite, which was first minted by King Alyattes in Lydia, Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). It bears a striking carving of a roaring lion’s head on one side and a double-square incuse punch created by a hammer during the minting process on the other. This punch mark is an imprint from the hammer used to force the coin onto the die that shapes the front, and it was also thought to show purity.

The coin is made of electrum, a gold-silver alloy that is harder than gold alone. It was referred to in the ancient world as “white gold” and commonly was used in trade at the time. The use of the coin spread to ancient Greece, and from there, the use of coins spread throughout the Western world. The Lydian one-third stater is thought to have been worth the equivalent of about a month’s salary.

The coins were minted sometime between 660 and 600 B.C., and by coin-collector standards, they aren’t particularly rare (you can pick one up for about $1,000–2,000). Much rarer denominations exist, though, with differing variations on the lion images, punches, and weight, including the Lydian stater (14 grams), sixth stater (2.35 grams), and twelfth stater (1.18 grams).

8The Oldest Still-Standing Wooden Building

The oldest wooden buildings to still stand are at the Buddist Horyu-ji Temple in Ikaruga, Nara Prefecture, Japan. Four of the buildings at the Temple survive intact, dating from Japan’s Asuka era.

Construction began in A.D. 587 under the orders of Emperor Yomei, as a form of prayer to recover from an illness. Kyoto was not yet Japan’s capital at the time, and Buddhism was still a young religion.

When he died anyway, his heir, Empress Suiko, and her regent, Prince Shotoku finished construction in A.D. 607. The original complex burned in 670 and was reconstructed sometime before 710. Given early Japanese architecture’s vulnerability to fire, it’s a miracle that the buildings have survived unscathed for so long afterward. The building complex consists of a central five-story pagoda, a Golden Hall alongside it, an inner gate, and most of a wooden corridor that surrounds the central precinct.

A few historians have cast doubt upon whether or not the fire that wiped out the original complex really occurred. If not, the complex would be even older. But even with the fire, the complex has seen continuous use for 14 centuries now and is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Today, the Horyu-ji Temple still serves its original purpose and houses treasures from the Asuka and Nara periods of Japanese history. The Temple even gets a mention in the Japanese classic The Tale of Genji.

7Oldest Depiction Of The Human Form

The Venus of Hohle Fels is the world’s oldest figurine to depict the human form. With the possible exception of the Zoomorphic Lion Man sculpture, it’s also the oldest undisputed figurative prehistoric art yet discovered (The Lion Man, however, depicts a non-human or half-human figure).

The 40,000-year-old statuette is about 6 centimeters (2.4 in) tall and carved from mammoth ivory. Like most Venus figurines, it depicts a voluptuous women with exaggerated, pronounced breasts and buttocks, and a massive, protruding vulva. Like many similar statuettes, this one had no head, but it has a carved ring above the left shoulder with worn surfaces that suggest it was worn as a necklace.

The number of figures found to date and the care our ancestors took in making them suggests that they were extremely important to early humans. Many researchers believe that they served as fertility totems, but the truth of their meaning is still largely unknown.

The Venus was excavated at the Hohle Fels caverns in the Swabian Jura region near the city of Ulm in southwest Germany, which was also the site of the world’s oldest musical instruments until new discoveries in 2012. The figure was found in six pieces about 3 meters (9 ft) under the cave floor amid animal debris, worked bone, and ivory and flint-knapping debris.

The Hohle Fels caverns contain plentiful evidence of prolonged prehistoric human occupation and has been the site of numerous finds, including the Lion Man figure. This sculpture was originally thought to be around 30,000–31,000 years old, but refined carbon-dating of bones found near the figure now put the Lion Man at 40,000 years. It’s also a noteworthy piece because the representation of an imaginary figure in art provides early evidence that humans had already developed complex pre-frontal cortexes.

6The Oldest Musical Instruments

In 2012, researchers discovered the world’s oldest musical instruments, 42,000–43,000 years old. The find was identified by Professor Nick Conard, the Tuebingen University researcher who was also the lead excavator of the previous record holder, also found in a nearby area in 2009.

The instruments are bone flutes, one of which was fashioned from mammoth ivory, the other from a bird’s bone. They were found in the Geissenkloesterle Cave in the Upper Danube region of southern Germany. Based upon the finds from this cave and others in and around the region, it is thought that humans entered the area 39,000–40,000 years ago, just before an extremely cold climatic period.

Professor Conard believes that the artifacts collected from the area indicate that the area served as a corridor for the flow of technological innovations into Europe at the time. Music could have been used for recreation or religious ritual and could have been part of a suite of behaviors that allowed early humans to out-compete Neanderthal man.

Some scientists believe that the ability to play music goes back even further. Professor Chris Stringer, a human origins researcher at the Natural History Museum in London who worked on instruments discovered in the Hohle Fels cavern in southwest Germany, believes that humans may even have possessed the trappings of advanced cultural creativity as far back as Africa over 50,000 years ago or even earlier.

5The Oldest Cave Paintings

Until 2014 the oldest cave paintings known were 30,000–32,000-year-old paintings of Upper Paleolithic animals found in the Chauvet Cave in the valley of the Ardeche River in France. With little evidence to the contrary, it has been widely believed that an explosion of symbolic artistic thinking in early humans began in Europe around this time.

But a new discovery on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, east of Borneo, challenges this notion. In September 2014, scientists confirmed that some of the cave paintings discovered there could be over 40,000 years old. They consist of stenciled handprints (similar to handprint paintings found elsewhere around the world), and paintings of local animals. One painting of a local animal called a babirusa has been definitively identified as at least 35,400 years old, making it officially the oldest known work of figurative art.

Art probably developed independently all over the world. There has been other evidence that Europe was not the sole place of origin. The presence of red ochre dye (commonly used in cave paintings) has been found in Israel dating to 100,000 years ago, and paint-making containers have been discovered in Africa that also go back as far as 100,000 years. This last example is also the world’s oldest known container, as we’ve previously discussed.

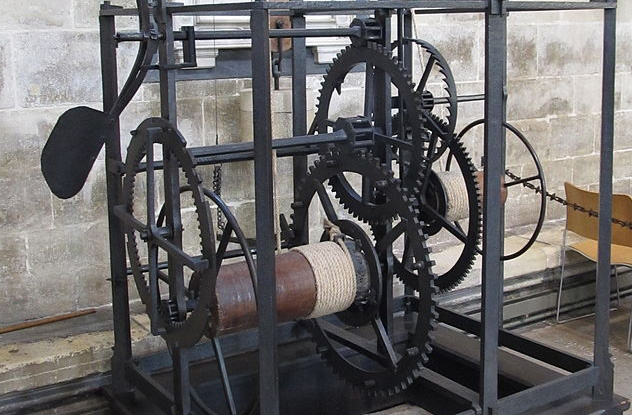

4The Oldest Working Mechanical Clock

The world’s oldest working timepiece is a massive mechanical clock located at Salisbury Cathedral in southern England. Commissioned by Bishop Erghum around 1386, it consists of a wheel and gear system attached to a cathedral bell by ropes. It chimes on the hour. A mechanism inside the workings called a “verge and foliot” controls the clock.

The word “clock” comes from glocke, or “bell” in German, and early clocks usually worked with bells in this way. Before clocks such as these came into use, only astronomers made regular use of clocks, and sundials or water clocks were the most prevalent sorts of clocks used by communities. While European astronomers divided the day into 24 hours, most people divided the day into 12 day and night hours that varied in length from day to day. The adoption of mechanical clocks marked the beginning of more accurate timekeeping.

Another mechanical clock, slightly older, was commissioned in Milan, Italy by 1335 but no longer works.

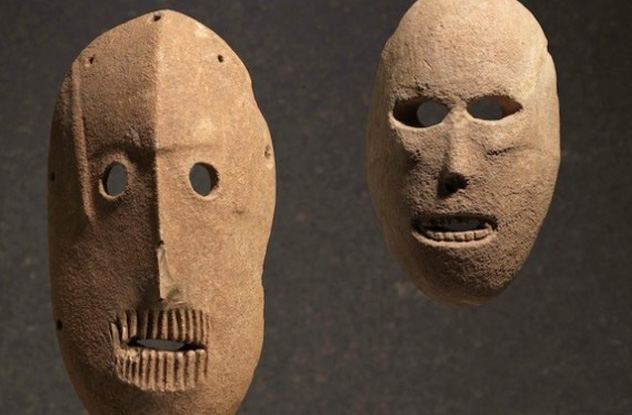

3The Oldest Masks

The oldest masks ever found are a collection of 9,000-year-old stone masks from what is now Israel during the Neolithic era. They were collected from sites in the Judean Desert and the Judean hills and are currently on display in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

The masks themselves are stylized faces (at least some of them may have represented skulls), with holes along the edges that may have allowed for them to be worn. The holes may have alternatively been used to thread hair through them for a realistic effect, or cords to hang them from pillars or altars. Researchers are unsure whether they were worn or used ritualistically, but they note that the carved features seem to be designed with human comfort in mind. For example, the eyes are carved to afford a wide field of vision.

Older cave drawings depict people wearing masks. Archaeologists believe that many were made of biodegradable materials, so they are lost forever, making the few that we do find all the more valuable.

2The Oldest Example Of Abstract Design

In 2007, archaeologists studying mollusk shells gathered from the island of Java in Indonesia discovered one that appeared to have etchings on its surface. Others had characteristic holes near where the shells joined together, indicating that someone had used tools on them.

In 2014, a team of researchers confirmed that the shell was probably a tool of some sort. The etchings were the work of humans, probably Homo erectus, who had been thought only capable of using stone tools. Even more astonishing, the zigzag pattern of the etchings indicated the oldest known example of abstract representation in hominids to date.

The team, led by Josephine Joordens of Leiden University in the Netherlands, dated the shell to be about 500,000 years old. They established that the marks were carved and not accidental by using a microscope to demonstrate that they were made in a single session with sharp turning points at the corners—a sign of confident agency. They also determined that the holes carved in many of the shells were made with shark’s teeth, which were also found at the site. Because the etchings showed unmistakable signs of weathering, a hoax or recent marking of the shells by researchers was ruled out.

Still, it’s premature to call the evidence conclusive. It isn’t clear that Homo erectus had a prominent presence on the island. The carving may have been the later work of Homo sapiens. Until more examples can be found, no firm conclusion can be made, but even if it doesn’t turn out to be intentionally symbolic, it’s at the very least the oldest doodle ever found.

1The Oldest Tools

The oldest tools ever found were discovered in Gona, Ethiopia and are 2.5–2.6 million years old. Not only does this make them the oldest tools, they are the oldest human artifacts in the world to date.

The tools are referred to as Oldowan, after the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzanio, and consist of pieces of sharp-edged rock pounded off of cores. They are used to chop and to scrape meat from animal bones.

About 2,600 of these tools have been uncovered from the excavation site, but no human remains have been uncovered, leaving the identity of the toolmakers debatable. What is known is that they predate the oldest known remains of genus Homo in the area. Similar tools have been found in other parts of Africa, with the oldest finds dated at about 2.3–2.4 million years ago.

Lance LeClaire is a freelance artist and writer. He writes on science and skepticism, atheism, and religious history and issues, and unexplained mysteries and historical oddities, among other subjects. You can look him up on Facebook, keep an eye for his articles on Listverse, or follow his brand-new sometimes-serious, sometimes-satirical blog on atheism and secular issues at lleclaire.wordpress.com.