Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

10 Rare Artifacts With Fascinating Backstories

Like a shadow, history is attached to every pot shard, pebble, and bone. Nothing on this Earth is without a backstory. Archaeology is all about finding these missing shadows and sewing them together to better understand bygone times.

Rare stories are particularly valuable. They offer glimpses into the personal lives of ancient business owners and why neighboring cities fought. Unique finds also solve mysteries, create new world records, and even challenge the current timelines.

10 Earliest Down Syndrome

The genetic disorder known as Down syndrome is ancient. Throughout the centuries, artists have depicted the condition in paintings and sculptures. The oldest case involving human remains came from France. A necropolis in the northeast produced 94 skeletons, and one of them was a child. Found in 1989, it was determined that the youngster was between five and seven, gender unknown, and lived during the fifth or sixth century.

Preliminary analysis suggested that the child had Down syndrome, although it was never confirmed. Modern technology gave scientists that chance. A scan of the skull found strong signs of the condition—extra bone, abnormalities with the sinuses and teeth, thin cranium, and flattened base.

The findings offered a unique opportunity to see how an ancient community treated the child. Everyone in the necropolis was buried with a certain body posture, including this youngster. This suggested that he or she was neither discriminated against in life nor ostracized in death.[1]

9 Ediacaran Mystery Solved

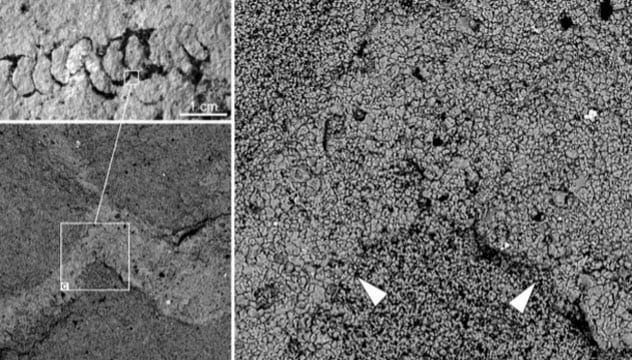

The Ediacaran period ran from 635 to 541 million years ago. From this era, a fossil type stumped the scientific community. Nobody could agree on its nature. Some felt that Palaeopascichnus linearis was fossilized poop. Others voted for ancient organisms or the markings left by them. Getting a clear answer was difficult since many Palaeopascichnus sites were protected areas.

In 2018, scientists caught a break. Over 300 specimens were discovered in Siberia, plus an extra batch was found in old collections from the 1980s. This combined cache allowed researchers the chance to dismantle the mysterious fossils.

After they were sliced, diced, and viewed under microscopes, the truth dawned. They were exoskeletons. Remarkably, this “armor” was made of sediment and served as extra protection for a sea-dwelling species.

Dating between 613–544 million years old, P. linearis became the oldest, non-microscopic critters with skeletons. The organisms could have been amoebas since they resemble xenophyophores, living amoebas that build their own sandy exoskeletons.[2]

8 Ancient Hashtag

Archaeologists who love cave doodles recently enjoyed two milestones. In 2015, they discovered the oldest art made by humans. Then, in 2018, they found the (slightly younger) oldest figurative art. The latter turned up in Borneo.[3]

The image, a cow of some sort, was large and painted between other colorful endeavors, including ancient hand stencils. Tests pinpointed the bovine creature’s creation between 40,000 and 52,000 years ago. While that wins the trophy for the world’s oldest figurative drawing, the most ancient human art came from South Africa.

In the past, Blombos Cave had already produced notable hominid artifacts. More recently, researchers puttered through Blombos sediment when they found a small flake. Incredibly, around 73,000 years ago, somebody used red ocher to draw something resembling a hashtag.

Although this is a stunning find, the oldest-known art does not belong to humans. That honor goes to a Homo erectus local in Indonesia who engraved zigzags on a shell 540,000 years ago.

7 Oldest Footprints

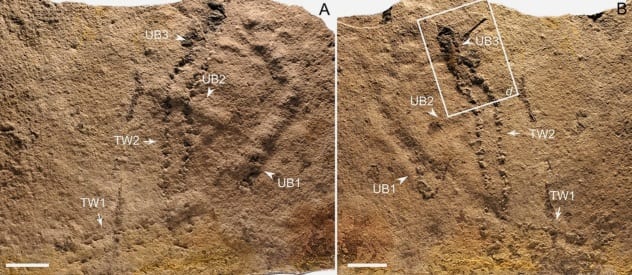

The planet is crisscrossed with ancient tracks. The oldest was found in 2018 and belonged to a mysterious animal. Around 551–541 million years ago, a creature traipsed around modern-day China. Today, the site is known as the Dengying Formation, but back then, the region was an ocean.

While paddling near the seafloor, the animal left behind two rows of footprints. There is only so much that spoor can reveal, but researchers determined that the creature was a bilaterian species. As strange as it sounds, that means the animal had a head on one end, a bum on the other, and symmetrical left and right sides.

In addition, the marine wonder had appendages that left the prints. These limbs are the main suspects in the creation of several burrows found nearby. The fossilized grooves suggested that the creature dug to satisfy a need, perhaps looking for food.[4]

Not only does the mud-scooping thing beat all dinosaur tracks by millions of years, it also proved that limbs evolved much sooner than previously believed.

6 Unique Sumerian Artifact

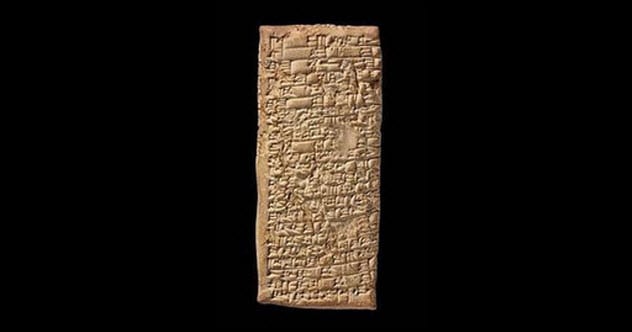

After being forgotten for 150 years, a pillar recently resurfaced at the British Museum. The marble was inscribed with Sumerian cuneiform and told the story of a war.

Around 4,500 years ago, the city-states Umma and Lagash were neighbors in ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day southern Iraq). They might have gotten along but for one thing—a fertile patch of land nearby. Since neither was in a sharing mood, the relationship soured.

The king of Lagash ordered the pillar to be made. Its purpose was to mark Lagash’s border to include the desired land and to smoothly insult one of Umma’s gods. The snarky pillar contained the conflict’s entire history. Within the text, the writer had inscribed the name of the deity so that it was almost unreadable.[5]

It happened on purpose as the name of Lagash’s own god was perfectly done with painstaking effort. This taunting wordplay is unique in cuneiform artifacts. The stele also counts among the earliest written border disputes, including the first usage of the phrase “no man’s land.”

5 Ancient Customer Complaints

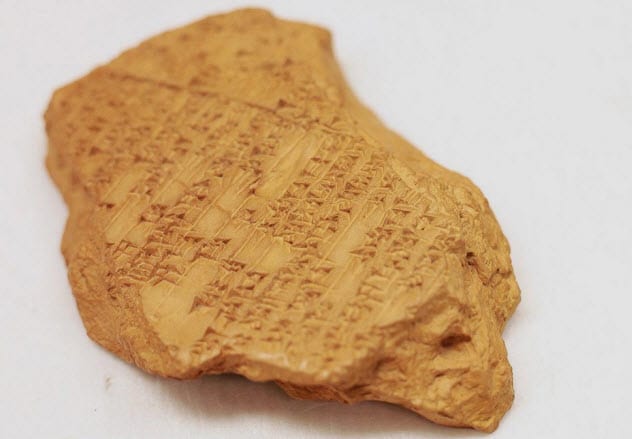

In 2018, archaeologists nosed around a house. The ruins once belonged to a businessman from the ancient city of Ur (in modern-day Iraq). He kept a slew of customer complaints.

Back in the 18th century BC, annoyed buyers could not send an email. They had to chisel their dissatisfaction in cuneiform script on clay tablets. Those in the home of Ea-Nasir, a copper dealer, are the earliest records of irked customers. Their complaints make it clear that Ea-Nasir was shady and even rude.

According to the tablets, he thought nothing of withholding copper that had been paid for and ignoring repeated requests for delivery. He also had a reputation for making people angry.

Researchers looked into historical records and found that Ea-Nasir started out as a trusted dealer at the Ur palace. By the time the complaints came in, he was already getting a bad name.

Records also showed his desperate attempts to start other businesses, some as bland as secondhand clothing. This suggested—and his cramped house supported this—that Ea-Nasir had lost his clients and wealth.[6]

4 The Guanyindong Toolmakers

Something in China could shake the history of human migration. It all began with something called the Levallois technique. A long time ago, ancient Homo sapiens (our own species) used this style to create tools. Geographically, only humans from Africa and Eurasia used it 385,000 years ago. The same technique was used by Neanderthals but in Europe.

As the Levallois style allowed several tools to be made from a single stone, it became popular and spread. It was assumed that the technique never reached China until about 40,000 years ago. That was until China’s Guanyindong produced ancient tools. They were made with the Levallois style.

This person or these individuals did not live 40,000 years ago. The Guanyindong toolmakers plied their trade between 160,000 and 170,000 years ago. Since no skeletons were found, it is impossible to say which species chipped stones that day.

Neanderthals or even the enigmatic humans known as Denisovans could be responsible. Clearly, somebody migrated to China and took the knowledge with them. If it turns out to be Homo sapiens, it challenges the known migration history of our kind.[7]

3 Oldest Political Murder

During 1877, a grave was found at Leubingen in Germany. Among the elite burial goods was the so-called “prince of Helmsdorf.” His tomb led to the discovery of an entire civilization, including the ruins of a massive building. The latter covered some 470 square meters (5,057 ft2).

Recent analysis of the body revealed a man of 30 to 50 years old who fell victim to a gruesome murder. Researchers feel the attacker was a trusted subject like a bodyguard or even a friend or family member.

Three injuries describe his last moments, and they were horrific. An arm injury showed that he likely tried to protect himself. However, the murderer was an experienced fighter. A blow was delivered so brutally to the collarbone that it broke his left shoulder blade and probably punctured a lung.[8]

Worse, a long dagger was forced through his stomach. This was done with such strength that the blade went through the spine and cut several arteries. The death of the prince happened nearly four millennia ago, making it the oldest-known political murder in history.

2 Oldest Song

Around 29 clay artifacts surfaced in Syria during the 1950s. Since they were 3,400 years old, researchers were very curious about what they had to say. However, the tablets were shattered and their cuneiform writing was unusually hard to understand.

Today, this type of script is well understood. However, the Syrian tablets were written by migrants who borrowed cuneiform to record things in their own language, which was called Hurrian. This cultural spin caused scientists to recognize the usual symbols but not what they meant.

In 2018, after years of work, one tablet finally revealed its astonishing contents—the oldest-known song in the world along with what appeared to be the earliest-recorded musical notation.[9]

History’s “first” song is quite sad. It tells the story of a woman unable to have children and how she blamed herself. At night, she took offerings of sesame seeds or oil to the Moon goddess, desperately hoping that her prayers would change things.

1 Unknown Plague Strain

Nobody loves Yersinia pestis. This bacterium caused the medieval plague known as the Black Death, which killed millions. In 2018, researchers found an unknown variant in a woman from Sweden. She was interred at Fralsegarden and appeared to have died along with 78 others around 5,000 years ago.

Frighteningly, analysis found that she had died of a Y. pestis strain that caused pneumonic plague. This form is deadlier than the bubonic version which caused the Black Death. It came with a silver lining—as a clue to an old mystery.

During the New Stone Age in Europe, there was a mysterious collapse of mega settlements. Called the Neolithic Decline, towns of up to 20,000 people thrived and suddenly crumbled. The woman died during this time. If plague had swept through the settlements, the people would have destroyed them.

Signs of such wholesale deliberate destruction were found to have happened 5,500 years ago. The Swedish strain is also the oldest Y. pestis ever discovered. Its age absolved steppe migrants, whom history blamed for bringing plague to Europe. The woman’s strain showed older local DNA than the arrival of the steppe people.[10]

Read about more fascinating artifacts on 10 Times Small Artifacts Surprised Archaeologists and Top 10 Artifacts And Places Frozen In Time.