Humans

Humans  Humans

Humans  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

10 Jobs From The Early 1900s That Totally Sucked

We all have moments when we think we have the suckiest job on the planet. But our jobs are nothing compared to some common jobs in the early 1900s. There was no overtime pay back then, and people often worked 12 hours a day, six days a week.

Kids worked those long hours in the mines or the mills alongside one of their parents. Adults worked jobs that barely paid enough to put food on the table. There were no health care benefits, and no one looked out for the safety of workers.

10 Horse Urine Collector

In the 1930s, the Canadian medical establishment needed pregnant horse urine to make its estrogen. At that time, estrogen was used to relieve menopause symptoms. But getting the horse urine was a bit of a problem.

Horse farms in Canada had to hire men to collect the horse urine before it could be sold. This job involved watching over several pregnant mares at a time. When the mares would pee, the urine collector would rush over with a bucket and collect the urine. Since the mares showed little sign that they were about to pee, the collector had to be quick on his feet and rush with bucket in hand from one horse to the next.

The pay for all of this work? Barely anything.

Only a few milligrams of estrogen could be extracted from each liter of urine, meaning a urine catcher had to gather a lot of urine to earn more than a crumb on his dinner plate. With the invention of synthetic estrogen, collectors of pregnant horse pee were no longer needed.

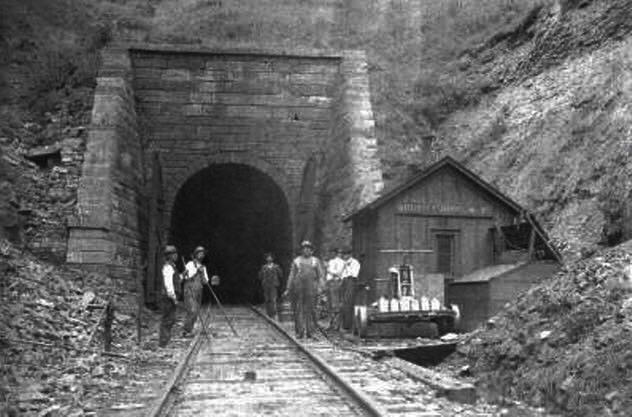

9 Tunnel Watchman

During the 1900s, trains moved goods from one side of the country to the next. At any given time, thousands of men, women, and children worked for the railroads. They made sure that the tracks were kept safe, the passengers were cared for, and the trains kept running. One especially unsavory position was tunnel watchman.

There are many different accounts of what tunnel watchmen did, and the job title seemed to vary slightly among railroad companies and regions. At the New Hamburg Tunnel in New York state, the tunnel watchman punched a time card at one end of the tunnel and walked to the other end of the tunnel, making inspections as he went. Then he would punch his time card again and head back through the tunnel. Back and forth he went for his entire shift, punching his time card at each end as proof that he was doing his job.

The Chicago & Northwestern Railway Company had a different system that included a tunnel watchman at each end of the tunnel. One watchman signaled the other at the approach of a train, and each man was in charge of keeping his section of the tunnel tracks free of debris and obstacles. Failure to keep the tracks cleared could easily lead to the death of a watchman, as could fires, derailments, and being on the tracks at wrong moment. A watchman often remained in a small shack (pictured above) at the end of the tunnel.

8 Canal Digger

Although the French started construction of the Panama Canal in the 1800s, the US took over the operation in 1902 under President Theodore Roosevelt. The main reasons for the switch were serious engineering problems and the large number of men dying from disease. Construction of the canal under the French claimed the lives of over 20,000 workers. Under the US, roughly 5,600 more men lost their lives.

Armed with over 100 “modern” steam shovels, the men who dug out the canal endured long hours and backbreaking work, but that wasn’t the main danger they faced. Early on, malaria and yellow fever claimed many lives during the building of the Panama Canal.

At first, medical workers were convinced that dirty conditions and bad air were to blame for the outbreaks. However, by the early 1900s, doctors learned that these diseases were transmitted by mosquitoes. Efforts were made to remove breeding grounds and get rid of standing water to reduce the mosquito population.

7 Spragger

In coal-mining regions, the fastest boys were put to work as spraggers. Beginning around 6:00 in the silent video above, you can see a spragger at work in a Pennsylvania anthracite coal mine.

These daring boys would carry 20 to 30 long pieces of wood, called “sprags,” while keeping up with the mine cars as they went down hills. To prevent the mine cars from going too fast and speeding off the track, spraggers would jab the sprags into the wheels of the mine cars to slow them down.

This was a dangerous job, and accidents were frequent. Fingers were easily pinched and sometimes lost in the process of slowing down the mine cars. The cars could also fly wildly off the tracks and crash into the boys, walls, or anything else in their way. Many boys were crushed and killed by mine cars or electrocuted after coming in contact with an electric trolley wire.

6 Gandy Dancer

The gandy dancers did backbreaking work. These men were the poorest of the poor—immigrants from Ireland, Italy, China, and Mexico as well as African Americans from the South. Hired by the railroad companies, they used sturdy metal poles to lift the railroad tracks and push gravel underneath. They worked in groups of four or more men, with each group caring for roughly 24 kilometers (15 mi) of railroad track.

Their work looked like dancing. As a call man sang or called out a rhyme, the gandy dancers tapped their gandy sticks on the track, pushing on the third or fourth beat of the song. No one is sure where the term “gandy dancer” originated. Some say it was taken from the Gandy Manufacturing Company in Chicago. But no one has been able to verify that a railway equipment company with that name ever existed.

By the 1950s, it no longer mattered. Railroad track repair was finally done by machines, and gandy dancers were no longer needed.

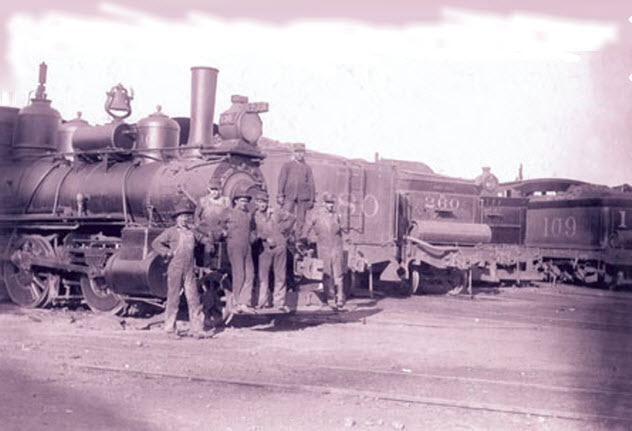

5 Fire Knocker

Fire knocker was another hellish job offered by the railroad companies. After a train completed its run, it was parked in a railway yard. The fire knockers would clear the engine of fire and cinders over a cinder pit in the yard. They would then wash the hot engine in water to cool it down and reload it with coal for the next run. Pictured above is the 1908 day crew of fire knockers for the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad.

This job may sound simple. But without fire safety gear or any safety standards, these boys and men risked their limbs and lives as fire knockers. Many cases were brought against the railroad companies for injuries and deaths. However, the railroad companies were usually found faultless.

In a case brought before a Texas court in 1921, the court decided that it was the fire knocker’s fault for trying to maneuver a faulty ash pan, not the fault of the company that owned the train. The injured fire knocker’s request for a rehearing was denied. In the early 1900s, railway companies had more pull in the courts, and a worker’s right to a safe working environment was just a novel idea.

4 Breaker Boy

Life inside the coal mines was rough for the men and even worse for the boys that worked as breakers. Breaker boys were hired at 8 to 12 years of age and worked for 12 to 14 hours a day hunched over chutes. They spent their long hours sorting the coal and shale brought out of the mines.

These young boys were often covered in black dust that also coated the inside of their lungs. Historical accounts say that you could see the black dust coming out of their noses when the boys exhaled.

The least fortunate of these boys got injured on the job. Cuts, scrapes, and broken bones were common. Sometimes, a boy got chewed up in the machinery or fell to his death down a coal chute. Due to the hunched position in which they worked, some of these boys became permanently deformed. Those that survived intact often went on as men to work deeper in the mines.

3 Lighthouse Keeper

The job of a lighthouse keeper wasn’t as dangerous as working in the coal mines or for the railroad. But the work hours were long, and there was little time off to do other things.

Before lighthouses used electricity, they had caretakers. This usually meant that a man, his wife, and possibly their children lived at the lighthouse full time. The day’s work began before dusk when the lamp was inspected and refueled before lighting. After the lamp was lit, it had to be watched overnight to make sure it remained bright. The lighthouse keeper also had to watch for shipwrecks during the dark nights and especially during bad storms. At daybreak, the lamp was turned off, and all of the equipment was cleaned.

Aside from the all-night duties, the keeper and his family were responsible for the upkeep of the lighthouse and the surrounding property. Many grew vegetable gardens to help provide them with food. With some of the lighthouses on secluded islands, day trips needed to be planned well in advance. These families made rare trips to the nearest towns to resupply themselves with essential items.

Other lighthouses were land based and close to port cities. Lighthouse jobs at these locations were coveted by lighthouse keepers with families because they had easy access to entertainment and necessities.

The job has been described as lonely, tedious, and boring. It took a certain kind of person who did not mind the solitude and monotony to handle the job.

2 Copper Mine Trammer

Deep in the copper mines, trammers would fill rock cars full of copper ore. Using nothing but their own strength, they pushed these heavy loads to the chutes, where the loads were brought to the surface.

Although we can all imagine that this was backbreaking work, this is another job that sounds simple but isn’t. The risks to life and limb were an everyday reality. Even though machines became able to do much of the hauling by the year 1900, some railroads continued to use trammers for another 10 years or more.

According to a survey by the Workmen’s Compensation Committee, roughly 1,463 trammers were injured in the copper mines in 1910. Eleven of those injuries were fatal. However, there were no reported deaths that year for bell ringers, blacksmiths, chute men, or many other positions at the copper mines. The only employees who had a higher death toll that year were the miners themselves. They had 43 fatal accidents but only 1,411 reported injuries.

1 Bindery Girl

In the early 1900s, women didn’t have it much easier than men in the workforce. The mills were horrific places to work because of fire hazards and dangerous equipment, but so was work in the binderies.

Bindery girls were hired by book presses to sew book pages together. At first, this was all done by hand. However, as equipment was introduced into the process, more injuries started happening. In a case reported in the Los Angeles Herald in 1908, a young woman named Freida Stahl became tired while working and accidentally got her fingers caught in the rollers of a folding machine, which began drawing her hand inside.

If it weren’t for her coworkers, the machine could have crushed her entire hand. She was fortunate that only two of her fingers were completely crushed. Her index finger was partially crushed.

The pay for this job? About $15 a week for 48 hours’ worth of work.

Elizabeth spends most of her time surrounded by dusty, smelly, old books in a room she refers to as her personal nirvana. She’s been writing about strange “stuff” since 1997 and about bread baking since 2008. She currently maintains a blog about writing Kindle books.