Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Body Parts That Went On Adventures Alone

We’ve looked at what happens when entire bodies are stolen from the grave, and it’s pretty morbid stuff. But occasionally, people’s body parts—real and fake, from the living and the dead—just sort of take off without them. With a little help, of course.

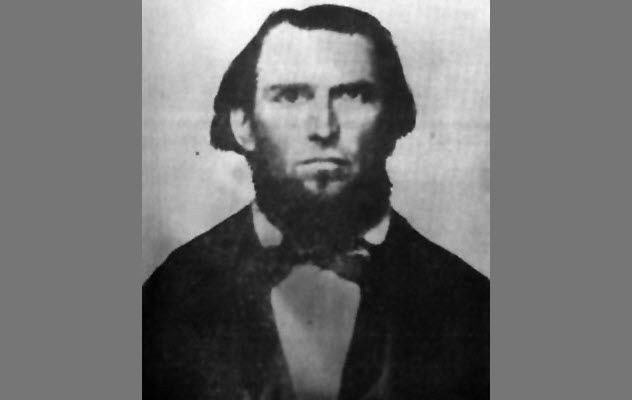

10 Isaac Ebey

Head And Scalp

The Ebey family is buried in the Sunnyside Cemetery in Coupeville, Washington. Isaac Ebey, the patriarch of the family, is at the center of a bizarre mystery.

Ebey was one of the first white settlers on Whidbey Island in Washington State. In a letter to his brother, Ebey called the island “a paradise of nature.” In fact, it was such a paradise that it shouldn’t have been surprising that someone else had gotten there first. Conflicts between white settlers and Native Americans became so violent that the USS Massachusetts was eventually dispatched to protect settlers and shipping interests. When the ship fired on a native settlement and killed most of the people there, the survivors vowed revenge.

It came on August 11, 1857. A group knocked on the door of Ebey, who was a Collector of Customs. When he answered, they cut off his head and fled with it.

Just what happened to the head is still up for debate. Although some claim that it was recovered about two years later, family documents differ from official military records. According to the family, only Ebey’s scalp was returned in 1860, after his brother petitioned the military to seek justice. In 1859, a Captain Dodd supposedly purchased Ebey’s scalp from his Kake contacts in exchange for some blankets, a handkerchief, three pipes, some cotton, and some tobacco.

Ebey’s brother wrote in his diary about getting the scalp back, noting that it was in terrifyingly good condition and included Ebey’s ears as well as his hair. A few months later, Ebey’s brother wrote that he never had the chance to thank Dodd for returning the grisly memento because Dodd had died. But there are no records that the brother buried Ebey’s scalp or got the rest of Ebey’s head back.

Other records suggest that the scalp was passed on to his sister, who apparently showed it to a doctor as many as 10 to 12 years later. The scalp then went to a niece, and subsequent records suggest it found its way to a branch of the family in California. With no more mentions of Ebey’s scalp—or the rest of his head—the details of what happened are still unclear.

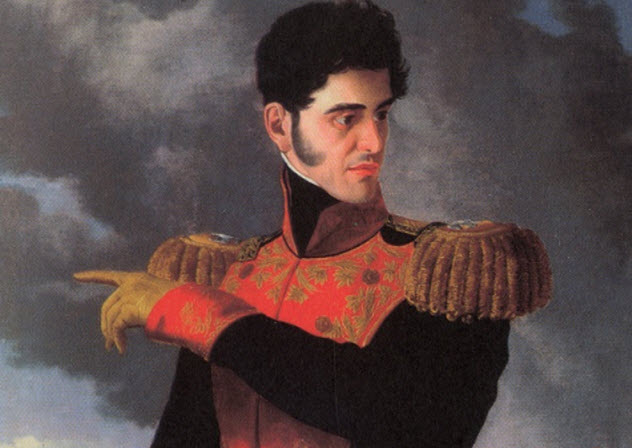

9 Santa Anna

Legs

In addition to being responsible for the development of today’s chewing gum industry, General Santa Anna is also at the heart of some bad blood between Texas and Illinois.

After the Battle of Cerro Gordo, Illinois soldiers on the battlefield stumbled across a carriage that contained gold and Santa Anna’s wooden leg. They took the leg with them, and for years, one of the soldiers displayed it proudly in his home. Eventually, the leg passed to the state’s military museum, where it’s been ever since. In another version of the story, the Illinois soldiers surprised the general while he was eating lunch. When he hopped on his horse and rode away, the soldiers picked up the wooden leg that he had accidentally left behind.

Either way, Texas wants the leg back, and Illinois isn’t giving it to them.

Although there are no concrete ties between Santa Anna’s wooden leg and the state of Texas, the San Jacinto Museum of History has been petitioning to get the leg back, even trying to collect enough signatures to take the matter to the White House. So far, they’ve been unsuccessful, and Illinois seems to be unwilling to return the leg voluntarily.

Strangely, Illinois has more than one of Santa Anna’s wooden legs. Although his real leg was buried with full military honors when it was amputated after close contact with cannon fire, Santa Anna had two replacement legs made—an ornate one and a pirate-style peg leg. The peg leg is now housed at the Oglesby Mansion in Decatur, after its illustrious (and alleged) career as Abner Doubleday’s baseball bat.

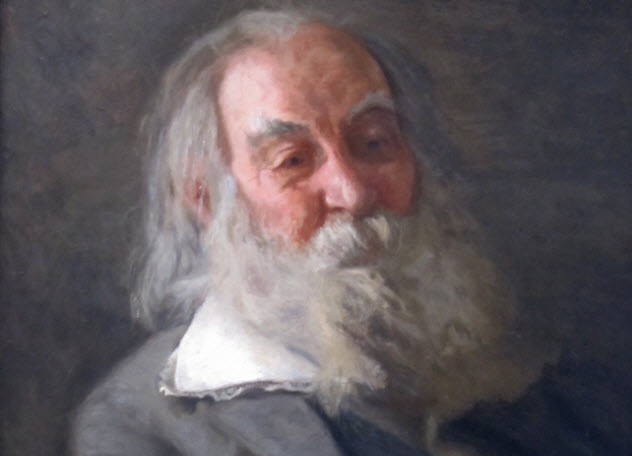

8 Walt Whitman

Brain

At the beginning of the 20th century, anatomists were still searching for physical signs in the brain that would explain why one person was great and another was a monster. Edward Anthony Spitzka had already examined the brain of assassin Leon Czolgosz for such signs without success. So Spitzka decided to examine the brains of extremely successful people instead. He was looking for something physical that would account for their greatness.

At that time, it was fashionable to donate your brain to science if you were of a certain class or standing and you wanted scientists to discover why you were so amazing. Spitzka got Walt Whitman’s brain. But in a 1907 publication, Spitzka casually commented that a lab assistant had been holding the brain when it dropped it on the floor and broke.

So they threw it away.

That’s the official story, but no one really bought it. When friends pushed the matter further, they got an official follow-up from the Wistar Institute of Anatomy confirming that the brain broke when scientists were trying to pickle it. However, another story suggested that the brain wasn’t broken but instead was lost somewhere at Jefferson College. Also, not a real answer.

When Spitzka started his study, he used high-class brains collected from the founding members of the American Anthropometric Society (AAS). The society didn’t keep records, and they didn’t take good care of the brains, either. When Spitzka received them, several of the brains were broken, their weights had been recorded incorrectly, and others were simply missing. One brain had been left in a hardening agent until it crumbled. Then there was Whitman’s brain, which was reportedly dropped.

According to the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review, the whole thing was a massive cover-up. No one seems to know whether Whitman was actually a member of the AAS or whether he or his family ever gave the AAS permission to remove his brain. In fact, no one seems to know much about the AAS at all. However, it’s been suggested that the society’s members, recognizing an opportunity that they couldn’t pass up, initiated Whitman into the AAS while he was on his deathbed and then made off with his brain after he died. But again, no one knows for sure.

7 Sarah Bernhardt

Leg

As the 19th-century equivalent of an A-list celebrity, French actress Sarah Bernhardt went on nine tours across the United States. Victor Hugo described her as having a voice of gold. In Europe, the audience reaction to one of her performances as Napoleon’s son was likened to the “deliriousness” of a Roman arena.

Although most of her body was buried at Paris’s Pere-Lachaise Cemetery after she died in 1923, her leg has been sitting in a storeroom at Bordeaux University. However, the school is quick to point out that there’s a difference between losing something and forgetting that you have it.

In 1898, Bernhardt was performing in a play called Tosca and needed to jump off the top of an onstage castle. Already 54 years old, she injured her knee in one of the jumps, and over the next few years, the chronic pain got to be too much for her. In 1915, she insisted that the leg be amputated above the knee. Afterward, an examination of the leg determined that it had been the right decision. Within a few months, she was making the rounds on the front lines of the war, visiting with and performing for the troops.

Bernhardt’s missing leg wasn’t rediscovered until 2009, although some people question whether the mystery has really been solved. As most of the pain was in her knee, the amputation was done above the knee. The recently discovered leg doesn’t have a knee, leading some people to believe there was a mix-up and it isn’t Bernhardt’s leg. Other people think we have found Bernhardt’s leg and that the knee was separated from the rest of the leg, dissected, and discarded.

6 Lord Uxbridge

Legs

According to one story, Lord Uxbridge and the Duke of Wellington were watching the Battle of Waterloo when a mortar arced over Wellington and hit Uxbridge in the leg. Uxbridge reportedly said, “By God, sir, I’ve lost my leg.” To which Wellington replied, “By God, sir, so you have.”

While that may sound like an understated British exchange, it’s actually not true. Uxbridge was in the midst of the battle when he lost his leg. He was taken from the field and moved to a house in Waterloo. The house belonged to Hyacinthe Paris, who watched the influx of high-ranking officers and doctors coming in to assess Uxbridge’s mangled leg. When doctors decided that the leg was beyond repair, they sawed it off.

Apparently sensing a profit opportunity, Paris asked to have the amputated leg. He placed it in its own little coffin and buried it in his garden with a tombstone that he charged people to come and see. Later, when Uxbridge returned to the house to visit the Paris family, he found that they were still eating dinner off the table where his leg had been removed.

However, no one’s sure what ultimately happened to Uxbridge’s amputated leg. Although the house isn’t there any longer, there are several conflicting stories that may provide clues to the leg’s whereabouts.

In one story, the leg was uncovered in Paris’s yard when a tree was uprooted during a windstorm. Little more than a bone at this point, the leg was supposedly moved into the house for display there. When Uxbridge’s son asked to have the leg returned, the Paris family tried to sell it to him instead. But a second story claims that the leg was eventually reunited with Uxbridge when he died. Yet another story says the leg is still buried in Waterloo.

Uxbridge’s artificial legs have gotten around, too. He owned three of a high-end model, called an “Anglesey Leg,” that had a hinged knee and flexing ankle. One each is kept at Plas Newydd in Anglesey, in the Musee Wellington in Waterloo, and in the Household Cavalry Museum of Whitehall.

5 Antonio Scarpa

Head, Thumb, Finger, And Urinary Tract

Antonio Scarpa is the neurologist credited with discovering Scarpa’s nerve, Scarpa’s ganglion, and the liquor Scarpae. Apparently, those who knew him would not have been surprised that he named all of his discoveries after himself. Once dismissed from a university position because he wouldn’t swear allegiance to the new king, Scarpa was a pompous jerk. He favored his many illegitimate children when it came to making appointments, spread rumors about the supposed criminal activity of people he didn’t like, and pointedly told people how he was intellectually superior to them.

Scarpa was so universally disliked that it wasn’t long after his death that people defaced his marble statues. Needless to say, he wasn’t missed. If his story has a moral, it’s to be careful how you treat your assistants, especially those responsible for your body after you die.

His postmortem was conducted by Carlo Beolchin, his former assistant. Beolchin and the other assistants who had worked for Scarpa turned his head, index finger, thumb, and urinary tract into preserved anatomical specimens. No one’s sure why they did it, aside from a morbid sense of vengeance toward the man who took all the credit and was undoubtedly horrible to them.

Scarpa, who never married and had no family to overrule his assistants, had his specimens meet the rather ignominious end of not even being put on display—until recently. On the 100th anniversary of his death, the Museo per la Storia dell’Universita di Pavia was founded, and Scarpa’s head was put on public display. The rest of his body parts were placed in storage.

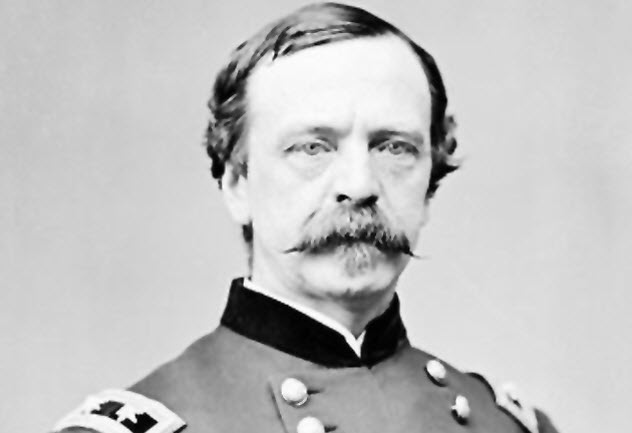

4 Daniel Sickles

Leg

In 1859, Daniel Sickles gained a certain amount of notoriety when he shot and killed his wife’s lover, Francis Barton Key (son of Francis Scott Key). Sickles was acquitted after using the insanity defense. He went on to serve in the military and was promoted to major general in 1862.

Sickles served at Gettysburg, even though there were huge numbers of people who wished that he hadn’t. Not one to listen to other officers or follow the plan, he had already royally screwed up at Chancellorsville. Royal screwups turned into outright disobedience when he was given orders at Gettysburg, and his actions led to the massacre of the Third Corps.

During the battle, Sickles’s leg was hit by a cannonball. Undeterred, he continued to sit on his horse and issue orders. Finally, his staff took him off the horse and transported him to a nearby field hospital. According to a story repeated by a number of Union writers, Sickles spent the entire trip to the hospital sitting up, smoking a cigar, and giving more orders. When his leg was amputated, he ordered that it not be discarded.

A short time earlier, the Army Surgeon General had issued a directive that called for the collection of “specimens of morbid anatomy,” and Sickles undoubtedly saw his chance for a bit of immortality. He had his leg preserved, put in a little coffin of its own, and sent to the Army Medical Museum with a note that read, “With the compliments of Major General D.E.S.”

Despite his disobedience on the battlefield, Sickles received a Medal of Honor and a position as an ambassador to Spain, where he remarried and had more children. His leg was put on display in the museum, and Sickles visited it every year on the anniversary of its amputation.

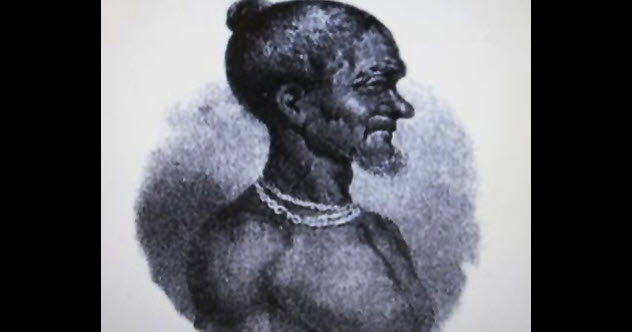

3 King Badu Bonsu

Head

In 1837, two Dutch emissaries were murdered in the court of Ghana’s King Badu Bonsu II. Their severed heads were displayed on the king’s throne as a clear message of how he viewed the Dutch presence in his country. The Dutch vowed revenge, dispatching an expedition that was supposedly a scientific one. The expedition bribed a member of the king’s court to gain access to the king and then captured, hanged, and beheaded him.

His head was sent to Holland, where it became part of a study on phrenology. That branch of science was discredited long ago, yet the king’s head remained in Leiden University. Kept in a jar and tucked away, it had been forgotten by the Dutch but not by those who remembered Badu Bonsu as their king.

In 2002, Dutch novelist Arthur Japin found the king’s head locked in a university cupboard while researching his book titled The Two Hearts of Kwasi Boachi. Ironically, his novel was the story of an Ahanta boy who was taken from his homeland in Ghana (then the Gold Coast) and brought to Holland. It was set in 1837, only a year before Major General Jan Verveer actually returned with the head of King Badu Bonsu II.

As Japin told The Independent, “The staff took [the king’s head] out of the round jar and put it on the laboratory sink for me. It had been turned white by the formaldehyde but it was still life-size and he looked as if he was asleep. I felt, ‘this is so wrong, you should go home.’ ”

The university disagreed. But a few years later, Japin was attending a state dinner with Ghana’s president and Holland’s queen. Japin told the dignitaries of his discovery, and the Ghanaians started a petition to get the head returned.

However, the process wasn’t easy. When Ghanaian representatives were sent to Holland, they were given the head to take back to their country. Although Dutch representatives apologized for a nightmarish history of slavery and repression in Ghana, the tribal elders who took possession of the head were angry because they were only sent to confirm the head’s identity. To actually retrieve the head was a huge breach of Ghanaian protocol.

It wasn’t revealed what would become of the king’s head when it returned to Ghana. According to rumor, the king had never been buried because it’s a major offense to inter an incomplete body. Only when the head was returned could the body be buried properly, if the Ghanaians were able to find where the body had been hidden away.

2 William Thompson

Scalp

On August 6, 1867, British immigrant William Thompson was working with a small group of men repairing telegraph lines in Cheyenne country. The lines had been cut by a group hoping to lure some of the settlers into an ambush. It wasn’t long until everyone was dead but Thompson. Later, he would tell how he was ridden down, shot in the arm, and clubbed with the butt of a rifle. As he lay there, he was stabbed in the neck and unable to respond as his attacker cut into his scalp and ripped it from his head.

Still conscious and motionless, Thompson watched as his attacker remounted and dropped the scalp. Once the group of Cheyenne left, Thompson got up, retrieved his scalp, and searched for help. Somehow, he found it. The first journalist to whom he told his story was Henry Morton Stanley, who recounted seeing the scalp in a pail of water. Stanley said it looked a bit like a drowned rat.

Thompson had kept the scalp in hopes that it could be reattached, but the surgery was beyond the capability of doctors at that time. They did try to reset the scalp, but they failed. As a grisly token, Thompson gave the scalp to one of the doctors who had attempted the operation. It was then passed on to the Omaha Public Library and finally to the Union Pacific Railroad Museum of Omaha.

Another journalist, Moses Sydenham, recorded Thompson’s testimony of what it felt like to be scalped for the Daily Sun: “The sensation was about the same as if someone had passed a red-hot iron over my head. After the air touched the wound, the pain was almost unendurable . . . I had to bite my tongue to keep from putting my hand on the wound. I wanted to see how much of the top of my head was left.”

1 Friedrich Schiller

Skull

Friedrich Schiller was a German poet and playwright whose story took some pretty bizarre twists—and we’re still not sure how it ends.

When he died in 1805, Schiller was buried in a mass grave in Weimar, Germany. Twenty-one years later, Weimar’s mayor decided to give Schiller a proper burial, so they dug him up. But no one knew which set of remains was his. After 27 skulls were exhumed, the mayor simply pointed to the biggest one and declared that it must belong to the intellectual.

That worked for a while. But in 1911, rumors that the skull didn’t belong to Schiller began to spread. When the mass grave was reexamined, 63 skulls were seen as possibilities. Another one was picked as Schiller’s skull. Those bones were moved into a crypt, which was disturbed yet again when the Nazis took possession of both Schiller’s supposed remains and the body of his friend, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

The Allies returned the remains to Weimar in 1945. However, in the mid-1950s, someone took another look at the remains and decided that the skull in Schiller’s sarcophagus belonged to a woman.

In 2008, Weimar finally agreed to have DNA tests performed on the skulls to determine which one belonged to Schiller. The answer was definitive—neither of them. While some people are demanding to know how so many people were fooled for so long, we still don’t know what happened to Schiller’s actual skull. Although it’s possible that it’s still in the mass grave, some historians suggest that Schiller’s remains were taken by grave robbers in the 1800s.