Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Fascinating Egyptian Structures That Aren’t Pyramids

Home to one of the world’s most famous civilizations, Egypt is a country filled to the brim with historical significance. However, when people explore ancient Egyptian history, they usually stop at the pyramids. But other remnants of the culture have survived, giving us new insight into how the ancient Egyptians lived.

10 Hatshepsut’s Mortuary Temple

We’ve already discussed Hatshepsut, one of the more interesting characters in Egyptian history. She’s the Egyptian queen who promoted herself to pharaoh because Thutmose III, her stepson and heir to the throne, was too young to assume the role. She also left behind a legacy—her mortuary temple.

Located at Deir el-Bahri, the temple is called “Djeser-djeseru,” which means “the holy of holies.” It stands proud to this day, but given the disagreements with Hatshepsut’s method of appointing a new pharaoh, both Thutmose III and Akhenaten went through the temple after her death and made some adjustments to the scenery.

On the first level was a beautiful garden filled with plants from Punt, although the garden is gone now. Behind it was a series of reliefs and monuments, most of which were destroyed by Thutmose III and Akhenaten after Hatshepsut’s death. While none of the surviving monuments depict Hatshepsut, one of them clearly shows Thutmose III dancing before the god Min.

The second level contains the birth colonnade and the Punt colonnade, the ancient Egyptian versions of a Facebook wall. The birth colonnade depicted Hatshepsut’s divine birth, which involved Amun-Ra using his breath to impregnate Queen Ahmose, Hatshepsut’s mother. The Punt colonnade featured Hatshepsut’s voyage to Punt and her return with boats filled with exotic woods, makeup, and animals.

Unfortunately, Thutmose III damaged the depictions of Hatshepsut. For his part, Akhenaten defaced the depictions of Amun-Ra because Akhenaten wanted to popularize the Aten, the god of the Sun disk, instead.

With four chapels, Senenmut’s tomb, and the sanctuary of Amun-Ra still standing, Hatshepsut’s temple offers insight into the ancient Egyptians’ way of life and their politics.

9 The Tuna El-Gebel Catacombs

The ancient Egyptian city of Hermopolis Magna was the capital of the Hare province. Known as the “City of the Eight,” the people there worshiped Thoth, the god of learning. Although the city is interesting in its own right, a fascinating discovery was made nearby.

On the west bank of Tunah al-Jabal near Hermopolis Magna, a university expedition in the 1930s unearthed a vast necropolis dedicated to Thoth. Called “Tuna el-Gebel,” this necropolis may extend all the way to Hermopolis Magna. Regardless, archaeologists have already uncovered 3 kilometers (2 mi) of this impressive site.

As expected, dead bodies lie within the catacombs, which allowed relatives and friends to visit their deceased loved ones without being affected by the weather. The tomb of Petosiris, one of the high priests of Thoth, is also contained within the necropolis. Perhaps more surprising is the large number of animals buried there.

The ancient Egyptians often dedicated animals to their favorite gods, and Thoth certainly had an entire bestiary by the time the Egyptians were done. Explorers discovered thousands of mummified animals, including baboons, ibis and ibis eggs, cats, larks, kestrels, and even pigs.

Every animal within the necropolis was deemed sacred. However, the baboons and ibis were especially exalted, given that Thoth was usually depicted with the head of an ibis and baboons were Thoth’s trusted followers that assisted scribes with their work.

8 The Colossi Of Memnon

The Colossi of Memnon are two giant statues that the locals refer to as “el-Colossat” or “es-Salamat.” Both depicting Amenhotep III, they were built to guard his mortuary temple behind them. While the colossi are still standing, the mortuary temple has vanished due to erosion caused by floods and the theft of stones by subsequent rulers.

Both statues have tiny representations of Amenhotep III’s wife and mother carved into the base as well as two Nile gods winding papyrus around the hieroglyph for “unite.” The statues are called the Colossi of Memnon because early Greek visitors believed the statues depicted the god Memnon, son of the goddess Eos.

After an earthquake in 27 BC, the northern statue suffered some structural damage that caused it to “sing” around dawn. Puzzled, the ancient Greek visitors believed that it might be Memnon, who had died at the hands of Achilles but had returned as a statue. According to their theory, Memnon cried out in anguish each morning when he saw his mother, Eos, rising in the sky at dawn.

Although we can’t reproduce this phenomenon in modern times, it’s possible that the singing was caused by dew trapped in the porous rock that evaporated from the heat of the morning Sun. The singing stopped in AD 199 after the statue was repaired.

7 Malkata Palace

When Amenhotep III ruled Egypt, he built a palace that was the ancient Egyptian version of a California mansion. He was only 12 when he inherited the throne from his father, Thutmose IV, along with one of the largest, wealthiest empires in the world. Rather than wage war, Amenhotep III was a man of diplomacy and peace, which left him the time and money to build Malkata Palace.

The site for Malkata Palace spanned about 800,000 square meters (9 million ft2). The luxurious structure contained a library, kitchens, administrative office, audience chambers, halls for festivities, and more, all of which were decorated lavishly with paint.

Its size wasn’t just for grandeur, however. Malkata Palace housed Amenhotep III’s family, servants, guests, and a large harem of princesses, all of whom had their own retinue of servants. One foreign princess visited with 300 servants of her own. Malkata Palace also housed all the visitors for the Heb Sed festivals—the jubilees of Amenhotep III’s coronation— which probably explains why he called this vast complex the “House of Joy.”

The most curious of all the discoveries made at Malkata Palace was its artificial lake. With a T-shaped area of about 3.5 square kilometers (1.5 mi2), the lake allowed Amenhotep III and his family to sail around without interruption.

6 Tanis

With its discovery rivaling that of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, the “lost city” of Tanis missed its moment of fame when current events overshadowed ancient ones. Tanis was called “Djanet” by the ancient Egyptians and “Zoan” in the Old Testament. During the 21st and 22nd Dynasties, Tanis was the capital of Egypt. But political troubles shifted the importance and influence of the city elsewhere.

In its prime, however, Tanis was a wealthy city, largely because it was one of the closest ports to the Asiatic seaboard. A large temple dedicated to the god Amun was built there. The city’s brief moment in the spotlight also meant that some of the royal tombs were quite extravagant.

In 1939, archaeologist Pierre Montet brought several years of excavations at Tanis to a satisfying end when he discovered a royal tomb complex. It had three burial chambers that were undisturbed by vandalism or theft, making this an incredibly valuable find that also included burial treasures like golden masks, silver coffins, and royal jewelry. Nobody had visited Tanis since the city was abandoned, so the tombs and other archaeological treasures were in the same state as during ancient Egyptian times.

But just as Montet announced his fantastic find, World War II erupted, shifting people’s attention away from Egyptian discoveries to current international turmoil. Although the discovery faded into history, it doesn’t change the fact that Tanis held some of the greatest archaeological finds since Tutankhamun.

5 The Temple Of Seti I

The Temple of Seti I is located in Abydos, one of ancient Egypt’s holiest sites. A burial site since the predynastic era, Abydos was originally dedicated to the god Wepwawet, who opened the way for the dead to enter the afterlife. Gradually, the worship of Osiris grew within Abydos until the entire area became dedicated to him. Abydos features the early tombs of the necropolis Umm el Qa’ab, which were thought to be the beginning of burial practices that eventually led to the building of the pyramids.

One of the remaining temples within Abydos is the Temple of Seti I, which has a strange, L-shaped layout but is like most Egyptian temples otherwise. Some of the temple’s surviving wonders include two hypostyle halls, large rooms where the builders supported the roof by placing many columns throughout the structure.

The outer hypostyle hall was finished by Ramses II after Seti I’s death. Even though the temple was supposed to be about Seti I, the pictures within the outer hypostyle hall frequently depict Ramses II. At the entrance, Ramses II is shown measuring the temple with the goddess Selket before presenting it to the god Horus. Elsewhere, Ramses II is depicted offering a box of papyrus to the deities Horus, Isis, and Osiris before being led to the temple to be blessed with holy water. However, these sunk reliefs aren’t crafted well, suggesting that Ramses II sent all of Seti I’s best workers to complete his own temple, the Ramesseum.

The more impressive sights are found in the inner hypostyle hall, which was largely completed before Seti I’s death. One relief shows Osiris and Horus pouring holy water over Seti I. Other reliefs depict Seti I being crowned by the gods and Seti I kneeling before Osiris and Horus. On the side walls, projecting piers show Seti I wearing a crown representing the combination of Upper and Lower Egypt.

Behind these halls are seven sanctuaries, each dedicated to a favorite god. There’s also the Sanctuary of Seti I, which depicts him uniting Upper and Lower Egypt, as well as inner sanctuaries of Osiris, several chapels, and a gallery of kings listing all of Seti I’s predecessors.

4 Babylon Fortress

The Babylon Fortress in Cairo (aka the “Castle of Babylon” or the “Castle of Egypt”) wasn’t built by the Egyptians. Instead, it was built by the command of two Roman emperors. The first one was Trajan, who opened a canal between the Red Sea and the Nile and refurbished an old Persian fortress in the southern part of town. The second was Arcadius, who improved upon the existing fortress. Given both of their efforts, Babylon Fortress became a port and a supply line to Alexandria.

The Babylon Fortress was a refuge for the Coptic Christians, especially after they began to suffer persecution from the Western Christians. There are several churches built into the fortress itself, including the Hanging Church, one of the most famous Coptic churches in Egypt.

The Hanging Church is built over the entrance to a passage in the fortress. Visitors enter through a decorated gate on Shar’a Mari Girgis Street and then climb 29 steps to the church (hence its nickname, the ‘”Staircase Church”). The church has an 11th-century pulpit with 13 pillars, representing Jesus and his 12 disciples. The oldest icon in the church dates to the eighth century. A lintel depicting Christ entering Jerusalem may date as far back as the fifth century.

3 Deir El-Medina

A village near the Valley of the Kings, Deir el-Medina housed all the workers who helped build and decorate the tombs for the pharaohs. According to village records, the people living in Deir el-Medina actively desired to build tombs that would one day serve their king. Many of these records also discuss personal matters, which gives us a look into the day-to-day life of Egyptian workers.

The tomb workers went on one of the first recorded strikes due to an unfair work environment. Ramses III had a huge construction program at Thebes, which heavily drained the grain supply used to pay the workers at the necropolis. The workers waited six months for payment. Then, faced with starvation, they marched on several temples and staged sit-ins until something was done.

According to the records of the strike found at Deir el-Medina: “They sat down at the rear of the temple of Baenre-meryamun. They shouted at the mayor of Thebes as he was passing by, and he sent to them the gardener Meniufer of the chief overseer of cattle to say to them: ‘See, I’ll give these 50 sacks of emmer for provisions until Pharaoh gives you (a) ration.’ ”

For researchers, interesting records from this ancient Egyptian village are available online at the Deir el-Medina database.

2 The Statue Of Meritamun

Unlike the other towns on this list, Akhmim is still active today, but it stands over the ancient Egyptian town of Ipu. When excavating the site, archaeologists discovered fragments of a statue of Ramses II and a relatively intact, 11-meter-high (36 ft) statue of Meritamun, Ramses II’s daughter.

Given that the female statue was lying prone, the workers righted it first. After that, it was decided that the statue should be left in the open, still situated several meters below ground level.

A story on looklex.com described it this way: “Akhmim is among the weirdest sites from Ancient Egypt. You drive along crowded and dusty roads in the large town of Akhmim, then suddenly, in a large hole in the ground, you see the head of a grand female statue.”

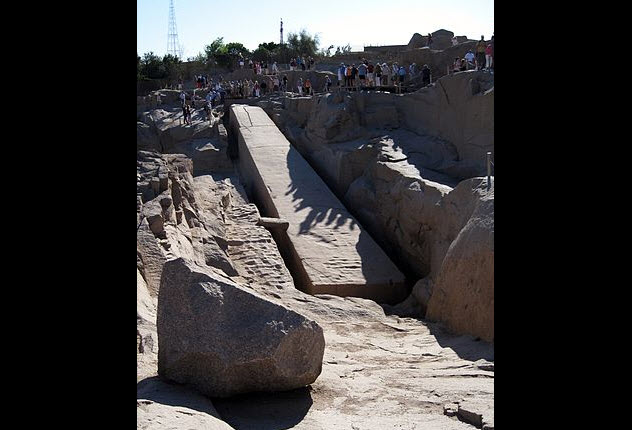

1 Aswan Granite Quarry

The Egyptians loved their granite. The pyramids were made of it. The temples used it. It was a prime building material that stood the test of time. Much of the granite used in these structures came from the Aswan granite quarry, which even supplied stone for the lintels above the king’s chamber. The Aswan quarry area spanned about 150 square kilometers (60 mi2) and included the famous granite quarries as well as lesser-known sandstone, grinding stone, and building stone quarries.

However, the most interesting aspect of the Aswan granite quarry is what lies unfinished inside: the largest ancient obelisk known to man. Had it been lifted out of the quarry to stand upright, this obelisk would have weighed 1,200 tons and sported a jaw-dropping height of 42 meters (137 ft), at least one-third taller than any other ancient Egyptian obelisk. Archaeologists believe that female pharaoh Hatshepsut commissioned its construction.

The reason for abandoning the project isn’t known. But it could be that the stone had imperfections that the ancient Egyptians hadn’t noticed before construction. Another theory is that the process of quarrying the stone relieved some of the stress keeping the stone together, causing a crack to appear on the obelisk. The project’s failure, however, has been a success for archaeologists, who can look over the work in progress to learn how the ancient Egyptians crafted such gigantic monuments.

S.E. Batt is a freelance writer and author. He enjoys a good keyboard, cats, and tea, even though the three of them never blend well together. You can follow his antics over at @Simon_Batt, or his fiction website, www.sebatt.com.