Politics

Politics  Politics

Politics  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Politics

Politics The 10 Most Bizarre Presidential Elections in Human History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

10 Paranormal Investigations And Encounters In Africa

For centuries, Africa was uncharted by European explorers. The continent was full of myth and mystery, the place where legendary creatures might actually exist in the deepest recesses of the interior. From expeditions to find proof of these animals to reports of vampires and demons, Africa has had more than its share of cryptozoological and paranormal treasure hunts.

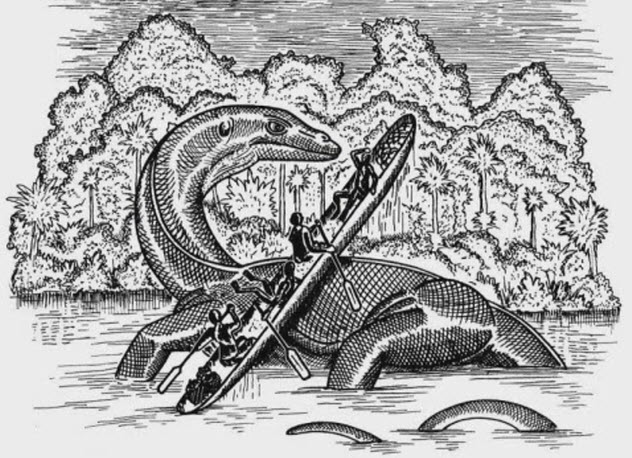

10 The Mokele-Mbembe

By 1912, one of the world’s foremost naturalists was convinced that there was a prehistoric creature living in the depths of Africa. Carl Hagenbeck was an early pioneer in zoology and the humane treatment of animals.

He wrote of identical stories from Rhodesia that told of a half-dragon, half-elephant creature that lived in remote swamps there. Supposedly, ancient cave paintings depicted the creature. But Hagenbeck’s expeditions met with disaster and returned with no new information.

The following year, Germany dispatched Captain Freiherr von Stein zu Lausnitz to explore the swampy jungle of West Africa and the Cameroons. The goal was a purely scientific one: The so-called Likuala-Kongo Expedition was to map the region, collect botanical specimens, and record any new animal life that they discovered.

The expedition was called off with the opening shots of World War I. Their reports fell into obscurity until they were published by the naturalist Willie Ley. According to Ley, the Germans had discovered what Hagenbeck had long been championing: a prehistoric-looking creature.

Von Stein zu Lausnitz called it the mokele-mbembe. He said that the creature lived in the unnavigable areas of the Sanga River (between the Pikunda and the Mbaio Rivers) and that there were rumors of it in the Ssombo River, too.

The natives told him that the creature was about the size of an elephant with a long, alligator-like tail, a neck that was reminiscent of the brontosaurus, and a long horn or tooth protruding from its head.

The herbivorous creature preferred to eat a white-blossomed liana and was known to attack boats that entered its territory. Von Stein zu Lausnitz also claimed that the natives showed him a path through the jungle that was made by the creature as it wandered along the Ssombo River.

9 The Ninki-Nanka

Richard Freeman is one of the more recent explorers to head into Africa in search of one of the continent’s most elusive creatures. According to legend, the ninki-nanka is a massive, crocodile-like reptile. Some of the wildest accounts claim that it can spit fire. However, most people agree that it has a horselike head, ridges (and sometimes wings), and shiny, reflective scales.

Freeman’s team interviewed one man who had supposedly seen the creature. He testified that it was around 45 meters (165 ft) long. After he watched the creature for almost an hour, he took deathly ill. He claimed that a potion from an Islamic holy man had saved him. According to those who believe in the ninki-nanka, there is little documentation of the creature because those who see it die soon afterward.

One witness claimed that a ninki-nanka had stampeded through a pumping station and destroyed equipment before they were able to chase it off by showing the creature its reflection in a mirror. One man saw the creature again and was dead two weeks later.

Freeman, a former zookeeper, is convinced that there’s a rational explanation for these cryptozoological sightings. After all, he suggests that the Loch Ness monster is really a set of sterile eels that are known to grow to massive sizes.

As for the ninki-nanka, he suspects that it might be a form of undocumented monitor lizard. Unfortunately, the major piece of evidence with which he was presented—pieces of the creature’s scales—turned out to be nothing more than rotted pieces of film.

8 The Ariel Event

When Harvard psychiatrist Dr. John Mack talked to the witnesses of an extraterrestrial encounter in 1994, he concluded that they were telling the truth.

On September 16, 1994, approximately 60 children between five and 12 years old were playing outside their school on the outskirts of the capital of Zimbabwe when they saw a large spaceship and several smaller craft gliding over the scrubland.

The spacecraft landed beside their playground. The children claim that they were approached by beings from the ships and that the whole encounter lasted about 15 minutes.

With all the adults in a meeting inside the school, it wasn’t until the kids returned to class that the adults realized that something had happened. The day continued normally, but it wasn’t long before the parents of children who wouldn’t stop talking about aliens started making phone calls.

In the days after the encounter, the kids were interviewed by Mack and Tim Leach, the BBC bureau chief for Zimbabwe. All the children told similar stories and drew similar pictures of what they’d seen. When filmmakers tracked some of them down in 2014, they stuck to their stories. It was also clear that their lives had been affected by the experience.

At the time, one little girl known only as “Elsa” said, “I got the feeling he was interested in all of us. [ . . . ] He looked sad and without love. [ . . . ] In space, there is no love, and down here, there is.”

She also said that the feeling of hopelessness persisted: “Like all the trees will go down and there will be no air. People will be dying. Those thoughts came from the man—the man’s eyes.”

Ten-year-old Isabelle said much the same in her interview: “We were trying not to look at him ’cause he was scary. My eyes and feelings went with him. [ . . . ] We are doing harm to the Earth.”

All the children described the man as small with long, black hair and huge eyes. They said that he didn’t see the kids at first. When he did notice them, he headed back to his spacecraft and left.

This event occurred at the end of a series of UFO sightings in the area. Just what the children saw is still debated, but a planned documentary will put all the evidence together and let viewers decide for themselves.

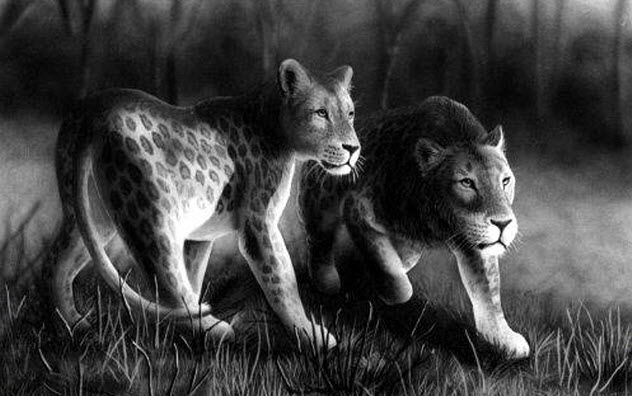

7 Marozi

Reportedly, the marozi (“solitary lion”) is a large, spotted cat that has been seen throughout East and Central Africa. According to witnesses, the creature is smaller than a typical lion. Although it resembles its more well-known cousins, the marozi has a coat that’s covered with gray-brown spots across its back and sides.

Skins have been preserved by hunters who have come across the strange cat. In 1924, A. Blayney Percival supposedly shot a spotted lioness and her cubs. In the 1930s, Michael Trent shot and killed a pair of spotted lions that were responsible for raids on his cattle farm.

After sightings throughout Kenya in 1931, Kenneth Gandar Dower mounted an expedition a few years later to go into the mountains of Kenya and find the beast once and for all. He hoped to find a subspecies of lion that had adapted its size and coloring to survive in the mountains—a habitat completely unlike that of more traditional lions.

However, he only found some footprints that could not be concretely linked to any known species. Nevertheless, he published a book devoted to the spotted lion. When that hit the British press and the public, more people—mostly big game hunters—came forward about their encounters with the elusive marozi.

The case remains open. Some people claim that the spotted lion is completely mythical. Others believe that a small group of lions may have headed into the mountains for fresh hunting and breeding grounds and eventually developed into a small, agile, spotted subspecies.

6 Kongamato

Explorer Frank Melland headed to south-central Africa to spend some time living among the Kaonde people in the 1920s. While he was there, they told him of a creature called the kongamato (“overwhelmer of boats”). Melland dedicated an entire section of his book to the creature because it was important in the Kaonde culture.

He noted that the Kaonde had charms to protect them from the kongamato, a lizard-like, bat-winged creature that attacked boats and caused the waters to rise. Their belief was so powerful that those setting out on the river carried a paste made from the roots of the mulendi tree, whose powers could be called upon to drive away an attacking kongamato.

According to Melland, the area has also been known for telling tales about a brontosaurus-like creature that he largely discounted as lore. But the idea of the kongamato seemed to be something different. The native people describe it as a reddish creature with no feathers and a wingspan of 1–2 meters (4–7 ft).

When Melland showed some of the witnesses a drawing of a pterodactyl, they confirmed that this was the kongamato. It was blamed for the deaths of four people in 1911. Even though Melland suspected that those deaths were caused by severe flooding in the area, the Kaonde’s fear was real.

Melland tried to get someone to take him to see a kongamato, but no amount of bribery worked. He wrote, “The natives do not consider it to be an unnatural thing like a mulombe, only [an] awful thing like a man-eating lion or rogue elephant but infinitely worse.”

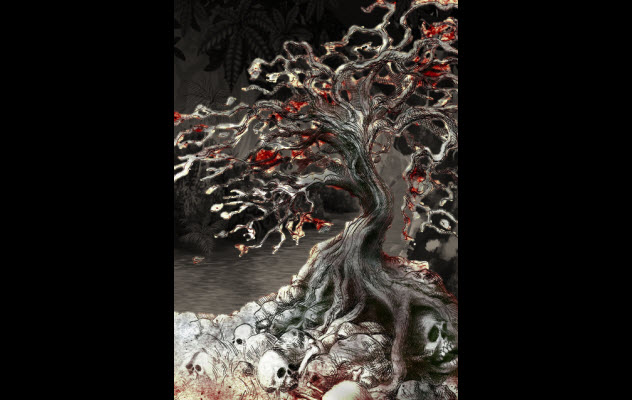

5 The Umdhlebe Tree

Cryptobiology, a weird sister science of cryptozoology, is the search for undocumented plants. Like the half-plant, half-sheep vegetable lamb of Tartary, most of these plants are strange.

When missionary Reverend Henry Callaway published The Religious System of the Amazulu in 1870, he told the story of the umdhlebe, a tree so deadly that skeletons littered the ground around it. Any bird that landed in the tree died, and it was also said to have a strange cry that sounded a bit like a sheep.

Callaway had seen people who had died because of the influence of the tree. In fact, the tree was so powerful that it could kill an entire village. Those stricken by the tree’s poisons were gripped by a fever, unable to sit or lie down, and reduced to simply pacing back and forth. It was a vicious disease that doctors did know how to cure.

A group of men from the missionary’s village went hunting and wandered into the territory of the umdhlebe. Unfamiliar with the tree’s appearance, the hunters used wood from the tree to cook a buffalo that they’d killed.

By the time the meat was cooked, they were too sick to eat—gripped by headaches, aching bones, swollen stomachs, and other sorts of intestinal distress. When the doctors reached them, some had already died after wasting away to nothing more than bones and swollen stomachs.

In 1882, G.W. Parker submitted a species profile to Nature magazine that described two species of umdhlebe tree. One species had large, dark green leaves and flaky bark while the other was more like a shrub. Anyone even approaching the tree would suffer from bloodshot eyes and headaches that would turn into a deadly delirium.

According to Parker, only a few people were capable of gathering the fruits of the tree, an anecdote supported by Callaway’s reports of doctors who used the fruits to prepare an antidote to the tree’s poison.

4 Koolakamba

French explorer Paul du Chaillu was the first person to interact with the Pygmies and the first to see a gorilla—an animal that was previously thought to be more myth than reality.

French explorer Paul du Chaillu was the first person to interact with the Pygmies and the first to see a gorilla—an animal that was previously thought to be more myth than reality.

When he wrote up his observations on Africa’s primates, he described four distinct creatures: the gorilla, the chimpanzee, the nshiego mbouve, and the koolakamba, which was named for its distinctive cry.

According to du Chaillu, the koolakamba was characterized by a large, prominent brow ridge, small muzzle, large ears, and a larger skull than the standard chimp. He also noted that the koolakamba had a short, stocky pelvic region as well as upper and lower teeth that met squarely.

The animal was familiar to people throughout the area of modern-day Gabon and Cameroon. One explanation for the animal’s widespread territory is simply that the features described by du Chaillu are well within the normal variations of the chimp species.

When W.C. Osman Hill did extensive documentation of primate physiology at New Mexico’s Holloman Air Force Base in the 1960s, he was convinced that du Chaillu’s field observations were right. However, some of Hill’s notes recorded different ear sizes and facial structure.

These differences caused other people to question if the two scientists had been looking at the same thing. One possible explanation is that the oddly shaped primate was a hybrid between a gorilla and a chimp. There have been a few documented cases of hybrid offspring between the two.

We still don’t have the answer to this mystery. Some photos, including recent ones from the Yaounde Zoo in Cameroon and older ones from Barnum & Bailey and the Dresden Zoological Society, appear to show a creature that’s not quite a chimp and not quite a gorilla.

3 Emela-Ntouka

The emela-ntouka is so obscure that it’s alternately described as a hoofed mammal and a reptile. But one thing remains the same: It has a bad temper and a single horn that allows it to kill elephants and other large creatures with a single blow.

The emela-ntouka is as big as an elephant. It has a frilled neck and a build reminiscent of a crocodile. The first reports of the emela-ntouka are dated around 1913.

Explorer Hans Schomburgk collected stories of the creature from the Klao tribe in Liberia. They told him about a small rhinoceros that lived deep in the rain forest. Although it was a strict herbivore, it killed whatever crossed its path.

In the 1950s, there were other close encounters with the creature. A French official working in the Republic of the Congo collected more reports of the dangerous creature, including sketches of the animal and its footprints.

Around the same time, Lucien Blancou, the chief game inspector of French Equatorial Africa, documented claims that the Kelle were terrified of a creature that had been seen disemboweling an elephant. However, the Kelle said that encounters with the creatures were on the decline and that at least one emela-ntouka had been killed a few decades earlier.

When Roy Mackal headed to the Congo in 1981 to search for the mokele-mbembe, he found more reports of the emela-ntouka. He believed that the creature might be a prehistoric survivor—a ceratopsian dinosaur—which was an idea that creationists jumped on.

Creationists at Genesis Park, an organization devoted to proving that dinosaurs and man coexisted, mounted an expedition to Cameroon in 2000. They were looking for the mokele-mbembe as well as any other proof for their theory.

When they started asking questions about the emela-ntouka, they found an answer to one of the things that was giving their theory a problem. Ceratopsian dinosaurs had frills. Early reports of the emela-ntouka didn’t involve a frill.

But when Genesis Park started talking to African natives, there were stories of the creatures having frills around their necks. Interviewees pointed out that illustrations of a triceratops and Mackal’s emela-ntouka were the same animal: the ngoubou, which had a frill around its neck.

2 The Bloodsucking Fire Brigades

Extending well into the 20th century, the native tribes in some areas of Africa believed that colonial police officers and firefighters were part of a vampiric entity that didn’t help people but instead sucked their blood.

In 1947, a chilling story spread about the Mombasa Fire Brigade. A man claimed to have seen members of the fire station kidnap a woman while she was sleeping and take her back to the station. Allegedly, these firefighters had also been seen carrying buckets of blood.

The story spread like wildfire. A mob quickly assembled at the fire station. It was only when rocks were thrown and arrests were made that the mob dispersed. But that’s not the only time that suspicion of vampiric activities by firemen and police escalated to terrifying levels. In the Swahili language, the connection was so concrete that wazimamoto (“fireman”) became widely used to mean “vampire” as well.

In the early 1920s, Zebede Oyoyo claimed to have been attacked by Nairobi’s fire brigade. During interviews, he said that he was accosted in a public toilet close to a police station. When he fought off his attacker, he was told that he was lucky—he would live. Later, he claimed that his Swahili dialect helped to protect him against the vampires because they saw his people as wild and dangerous.

In 1958, a man named Nusula Bua was arrested and sentenced to three years in jail for trying to sell another man to the Kampala Fire Station. Bua had heard that the firefighters were buying people for their blood.

When researcher and author Luise White interviewed members of African tribes, she discovered a widespread belief that the British were in Africa to take blood that was needed for their own people. Black—the color that most of the police and fire officials wore—was associated with African tales of demons and bloodsuckers.

There were also stories about people who went to hospitals and had their blood drunk. This idea may have come from the practice of donating blood or the way in which Arab invaders smeared their weapons with the blood of their dead enemies, believing that it gave them power over others.

1 The Popobawa

In February 1995, chaos broke out on Pemba Island when family after family claimed that they had been attacked by a creature called the popobawa. The creature was named after a monster that had supposedly gone on a sodomy rampage in the district a few decades earlier.

But those visited by the monster this time reported that they had been squeezed and restrained by the creature. They were also gripped by extreme terror until they finally passed out. The panic grew so much that people across the island spent the night camped outside. Hoping to find safety in numbers, they huddled around open fires with their neighbors.

By the following month, the panic had hit the mainland with reports that the old ways of the popobawa were back. That’s when the killing started. At least six men were beaten or killed because they were suspected of being the popobawa.

One eyewitness described a man in the town of Wete who was chased through town and beaten. Then he was taken under a lamppost to allow his assailants to get a good look at him. The assailants soon realized that the man wasn’t the evil creature that had been stalking the town. He was a mentally ill man whom they all knew.

Another man from the mainland was targeted because of a scar on his neck and medicinal herbs in his bag that smelled terrible—like the smell supposedly left behind by the popobawa.

The first death came in April 1995 when a man was beaten to death by a terrified mob. They found out later that he was also a mentally ill man who was on his way to a psychiatric hospital for treatment. By the time the panic ended, at least three people were dead.

But the question remained: What started the panic in the first place?

According to the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, the symptoms described were incredibly similar to those that go along with sleep paralysis and night terrors, making it likely that the popobawa was a tragic case of mass hysteria.