Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Undeniable Signs That People’s Views of Mushrooms Are Changing

Animals

Animals 10 Strange Attempts to Smuggle Animals

Travel

Travel 10 Natural Rock Formations That Will Make You Do a Double Take

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Hidden in Your Favorite Movies

Our World

Our World 10 Science Facts That Will Change How You Look at the World

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Undeniable Signs That People’s Views of Mushrooms Are Changing

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 Strange Attempts to Smuggle Animals

Travel

Travel 10 Natural Rock Formations That Will Make You Do a Double Take

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Hidden in Your Favorite Movies

Our World

Our World 10 Science Facts That Will Change How You Look at the World

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

10 Intriguing Visions Of The Future From The Past

The future always changes. From heroic space adventures in the 1960s to paranoid cyberpunk in the 1980s, you can learn a lot about the zeitgeist of an era by looking at how people imagined the future. This is also true of most early science fiction from the 18th and 19th centuries. Like today, writers back then projected their fears, ambitions, and prejudices onto a future society that we, as residents of a far-off epoch, can now appreciate with gimlet-eyed hindsight.

10 Memoirs Of The Twentieth Century

One of the first English-language texts to deal with the future was Memoirs of the Twentieth Century, written by Irish Anglican clergyman Samuel Madden and published in 1733. He claimed to have had the “honour and misfortune” to “have dar’d to enter by the help of an infallible Guide, into the dark Caverns of Futurity, and discover the Secrets of Ages yet to come.”

The book was touted as its subtitle, “Original Letters of State, Under George the Sixth, Related to the most important Events in Great Britain and Europe . . . from the Middle of the Eighteenth to the End of the Twentieth Century. Received and Revealed in the year 1728; and now published . . . in Six Volumes.” The reference to five nonexistent sequels to the first volume was a satirical jab at long-winded memoirs of the time.

The book’s format was a series of letters to the British monarch from ambassadors in foreign capitals in the years 1997 and 1998. There was little in the way of technological development in Madden’s vision, but there were great political changes: The Ottoman Empire was replaced by a Tatar dynasty, while the papacy ruled supreme with rich holdings in Africa, China, and Paraguay. It also featured interesting elements like a Mexican cheese that never rots, extant native states in North America, a messianic movement arising in Persia, and an army of Central African Jews marching on Egypt. However, much of the material was actually concerned with satirizing 18th-century political and religious concerns rather than serious speculation.

Memoirs of the Twentieth Century was published anonymously in 1733 but then immediately suppressed by both the author himself as well as British prime minister Sir Robert Walpole. This may have been because the content wasn’t actually speculations on the future but rather a thinly veiled satire of the Walpole government. Alternatively, it may have been because the identity of the author had become known, and Madden feared the effect of the work on his reputation. Of the 1,000 copies printed, around 900 were returned to Madden, who destroyed them.

9 The Reign Of George VI: 1900 To 1925

In 1763, another futurism-themed book was published in the United Kingdom. It’s often confused with Samuel Madden’s work but was actually an unrelated anonymously written text. The Reign of George VI: 1900 to 1925 was a sort of British wish fulfillment fantasy, describing the rule of a wise and brave monarch during the early 20th century.

The text portrays Britain as under threat from a Russia ruled by Czar Peter IV, who controls a northern empire which includes Scandinavia and a powerful and threatening navy. The czar was allied with France, which was very much the junior partner in the alliance to dominate Europe. George IV defeats Franco-Russian attempts to invade England in 1900 and forces a peace in 1902 after invading France himself while the Turks attack Russia from the south.

The next decade and a half are peaceful and prosperous for victorious England, with George IV investing heavily in the arts and sciences. He builds a new English capital at Stanley, in Rutland. The city is surrounded by artificial mountains and filled with neoclassical architecture and planned streets, complete with a palace filled with artwork from throughout Europe and Asia.

A second great war with the Franco-Russians occurs from 1917 to 1920. The English again score victories in Europe with the help of allied German and Italian states, though the Spanish joined the enemy side. It would end with the British conquest of France, Mexico, and the Philippines.

The postwar years would feature the development of a great canal transport system and the rise of manufacturing in both the British Isles and the American colonies (which apparently never declared independence). The book ends in 1925 with a great golden age. Perhaps the most unrealistic element is the happiness of the French population under the benevolent rule of an English monarch.

Some have admitted that despite the excessively pro-British sentiment of the text, there are some interesting parallels between Madden’s work and real history—20th-century Russian power, the rise of manufacturing in North America, and the strength of a British monarch named George VI during a world war.

8 L’An 2440

Louis-Sebastien Mercier’s novel L’An 2440 commences with an 18th-century Frenchman having a heated argument with an Englishman before going off to take a nap and waking up in the year 2440. (The English translation, Memoirs of the Year Two Thousand Five Hundred, changed the year to 2500 “for the sake of a round number.”) After some brief confusion in which the future inhabitants assume that the Frenchman is dressing up in historical clothing for the sake of making some philosophical point, he sets off on a tour of the far future.

Mercier was a great believer in Enlightenment thought, and thus, his future Paris is advanced in terms of social order, though not so much in technology. Compared to the 18th century, fashions are much freer and more comfortable. The 25th-century streets are much more orderly than the chaos of 18th-century transportation, with carriages are reserved for infirm judges and men of good character, rather than the nobility (who thus enjoy “more money and less of the gout“).

The future society has adopted rationality as the basis of their government and way of life, and the world is at peace. The narrator even encounters a statue of a black man with the inscription: “To the avenger of the New World.” In Mercier’s future, the European powers were eventually beaten back by slaves and the original inhabitants of the New World, and colonialism was finally abandoned for the good of all. However, Mercier also assumed that the values of Enlightenment Europe would spread worldwide, with the Chinese abandoning their writing system and adopting the French language as well as the Turks drinking wine and watching Voltaire’s play Mahomet.

The novel concludes with a visit to the palace of Versailles, which is reduced to “nothing but ruins, gaping walls, and mutilated statues; some porticos, half demolished, afforded a confused idea of its ancient magnificance.” There, the Frenchman meets Louis XIV, who has apparently been condemned to remain forever in the remnants of his empire’s former glory. Just before asking the monarch a question, the narrator is bitten by an adder and reawakens in the 18th century, bring the story to an abrupt conclusion.

7 The Mummy!: A Tale Of The Twenty-Second Century

Jane Webb was only a teenager when her mother died and her father’s fortune collapsed, and she was left destitute at 17 when her father also died. To make ends meet, she began to write poems and prose, and in 1827, she published a science fiction novel anonymously. This work, The Mummy!: A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century, featured a number of ingenious gardening machines that attracted the attention of botanist John Loudon, who met Webb and quickly married her. Jane Loudon would continue her writing career, but she strayed from speculative fiction into the realms of horticultural manuals.

The Mummy! is a proto-feminist work based on the revival of an ancient Egyptian mummy in the year 2126, a plot device likely inspired by the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt. The book describes a future England that has gone through a series of political and social upheavals and a long period of unhappy anarchy before stabilizing under the rule of female monarchs with a weakened Catholicism as the state religion.

Though some see it as a proto-feminist work, others argue that the traditional Georgian-era ideas and language of womanhood prevail throughout. There has also been some analysis claiming that the work was a traditionalist rebuttal to the atheistic and materialist thought of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. On the plus side, future women are generally educated, and their fashion seems interesting:

The ladies were all arrayed in loose trousers, over which hung drapery in graceful folds; and most of them carried on their heads, streams of lighted gas forced by capillary tubes, into plumes, fleurs-de-lis, or in short any form the wearer pleased; which jets de feu had an uncommonly chase and elegant effect.

There are also some interesting discussions of technology in between the distraction of a mummy brought back to life a by galvanic battery, who promptly steals a hot air balloon. Mail is delivered by steam cannon, with recipient towns catching their letters in a wire net. Meanwhile, steam powers moving bridges, automaton surgeons and valets, milking machines, lawnmowers, and all the luxuries of 22nd-century England.

6 The Year 4338

In 1828 Russian composer and author Vladimir Fedorovich Odoevsky wrote the story Dva dni zizni zemnago sara (Two Days in the Life of the Terrestrial Globe), which focused on a social gathering in 4338 that was disrupted by the arrival of Biela’s Comet, which astronomers of the time believed would collide with the Earth in that year. The comet actually burned up later in the 19th century.

From 1837 to 1839, he worked on a longer, though unfinished, prose piece further exploring the concept entitled 4338 i god (The Year 4338), which was not published until 1926. It was originally intended to be a part of a trilogy set chronologically in the period of Peter the Great, Odoevsky’s own time, and the far future, but this was never completed. Odoevsky’s work would ultimately languish in obscurity for almost a century before people started to reappraise his significance.

4338 purports to be a series of letters by Chinese student Hippolytus Tsungiev, who is visiting Russia in the early 44th century and maintaining a correspondence with a friend back in Peking. The letters were apparently reproduced in the 19th century thanks to specialist Mesmeric experiments. The future is dominated by the science and technology of Russia, with China slowly catching up and modernizing. Meanwhile, much of Western civilization has been lost to history, though apparently US tourists still exist.

Various fantastic technologies are described, such as a magnetic telegraph communication system, galvanic flying machines piloted by professors, recreational use of chemical elements, climate control, and military expeditions to the Moon. Sanit Petersburg is such a large city that it encompasses Moscow within its suburbs, while the cash-strapped English are selling parts of the British Isles to Russia.

On the other hand, many records of the distant past have been lost due to the degradation of paper. Horses have been bred into dog-sized pets, and some believe the tales of horse riders to be merely allegory. Those who believe men once rode horses contend that they were slowly replaced by flying machines following the birth of Christ. Scattered records of steam locomotives are assumed to have only been ridden by great heroes of a lost age, and there is much scholarly disagreement over exactly who the long-vanished Germans actually were.

5 Three Hundred Years Hence

Arguably New Jersey’s first science fiction author, Mary Griffith published her work Three Hundred Years Hence anonymously in 1836. It was included with a number of other stories in a volume entitled Camperdown; or, News from our Neighborhood. The work was perhaps the first utopian vision written by a US woman. It was positively reviewed by Edgar Allen Poe, and The New York Mirror noted: “The Ladies will read it with delight, for our fair author loses no opportunity of advocating the position and character of the gentler portions of creation—and the gentlemen will find in her pages much that they can turn to their account.”

Three Hundred Years Hence tells the story of Edgar Hastings, who lives in Philadelphia in 1835. Intending to catch a steamship, he instead falls asleep in a farmhouse, which is suddenly engulfed in a bank of snow. The steamship explodes, and his family assumes him dead. He stays frozen for 300 years until he is finally dug up by his descendants, who are cutting a road through a hill in the year 2135.

Hastings is astonished by the changes: Although few buildings from his time remain, there have been numerous technical and social improvements, which his descendants tell him are the result of educating poor women. Horse and steam transport have been replaced by a mysterious self-propulsion system that can be halted with a simple crank. The emancipation of women ended many of the evils of the past, including wars, trade monopolies, capital punishment, tobacco, and foot-binding in China. On the other hand, copyright is inheritable, and drunkenness is punished by forced labor, head-shaving, and summary divorce.

The issue of slavery seems to have been resolved by the government selling land to indemnify the slaveholders and pay for most of the African-American population to be resettled in Liberia and other parts of Africa. Described as “arranged most satisfactorily to all parties,” the new African nations are apparently prosperous, Christian, and peaceful. However, when asked about the fate of Native Americans, one of Hasting’s descendants mournfully refuses to speak of it except in the form of an ominous poem:

The Indians have departed—gone is their hunting ground,

And the twanging of their bow-string is a forgotten sound.

Where dwelleth yesterday—and where is echo’s cell?

Where hath the rainbow vanished—there doth the Indian dwell!

4 The Diothas

In 1883, John Macnie published The Diothas; or, A Far Look Forward under the pseudonym “Ismar Thiusen,” who is also the supposed protagonist of the tale. Thiusen, a 19th-century man, is sent through time to the far future by means of a mesmeric experiment. He arrives in the 96th century and finds himself in a great port city, filled with unfamiliar architecture and advanced technology, standing on the site of former New York. Macnie used the tale to explore an idealized version of the future, though unlike other utopian works of the period, it was formed from more conservative impulses.

Mancie’s ideal society is classless but neither communistic nor particularly democratic. Property is respected. Thanks to extensive mechanization, people have to work only three or four hours a day, but idleness is treated as a vice and a crime. There have been a number of astounding technological improvements, such as the development of ualin, a form of glass with the strength and malleability of metal. There are personal phonographs and stenographs in every household as well as paved roads with electric automobiles that can travel at speeds as great as 32 kilometers per hour (20 mph).

Interestingly, the text seems to have predicted the development of one traffic innovation: “You see the white line running along the centre of the road. The rule of the road requires that line to be kept on the left except when passing a vehicle in front. Then the line may be crossed, provided the way on that side is clear.”

Thiusen meets and falls in love with a woman named Reva Diotha, whom he realizes is a distant descendant of his 19th-century sweetheart Edith. Much of the narrative switches between sentimental romance and astonishment and exposition on the benignly undemocratic utopia. This comes to an end when Thiusen accidentally kills his new fiance after making an error piloting an advanced speedboat, though they manage to quickly wed before a fatal plunge over a waterfall.

3 Anno Domini 2000

In 1889, retired New Zealand premier Sir Julius Vogel wrote what is generally considered to be the country’s first science fiction novel—Anno Domini 2000; or, Woman’s Destiny. Four years before women won the right to vote in New Zealand, Vogel looked a century ahead to a world ruled by a prosperous and female-dominated British empire.

In Vogel’s 20th century, it’s be acknowledged that while men were physically superior to women, the reverse was true of intellectual capability, and therefore, most government posts are in female hands. After a near collapse of the British colonial system over the Irish question, pressure from the Dominions would lead the British empire to become a federated system with the monarch becoming the emperor of Britain, Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, South Africa, Egypt, Belgium, and more.

Aluminum air-cruisers powered by revolving fans have revolutionized travel, while communications are instantaneous through the “noiseless telegraph.” Hydroelectric power, industrialization, and a comprehensive social welfare system have relieved all poverty, and life is made easier through “remarkable contrivances for affording power and saving labor.” New Zealand becomes a major leader in industry, fishing, tourism, horticulture, wine-making, and Antarctic research.

Vogel’s tale focuses on former Imperial Prime Minister Hilda Fitzherbert, who is kidnapped by a villainous Australian republican who intends to seduce her. He fails, and Fitzherbert falls in love with the emperor, but this scuttles a deal to marry him to the daughter of the president of the United States. An Anglo-American war ensues, ending happily with US defeat and the absorption of New York and a number of other states into the Dominion of Canada.

Interestingly, when the book was republished in 2000, New Zealand women held the positions of prime minister, leader of the opposition, attorney-general, chief justice, governor-general designate, and CEO of New Zealand’s biggest company. Today, Kiwi authors of science fiction, fantasy, and horror compete for the Sir Julius Vogel Award thanks to his groundbreaking speculative fiction.

2 Golf In The Year 2000

Written in 1892 by Scottish author J. McCullough under the pseudonym “J.A.C.K.,” Golf in the Year 2000, or, What We Are Coming To tells the story of Alexander J. Gibson, who falls asleep for over a century and wakes up in the year 2000. Luckily, he wakes up in his home, where a surprised servant informs him of his plight and helps him to have his unkempt beard shaved off.

Though McCollough didn’t seem to take the book he was writing very seriously, he managed a number of pertinent predictions: The year 2000 features colored photographs, a form of television in which theater performances are transmitted by mirrors, and electric bullet trains called tubular railways, which are even used for three-hour transatlantic voyages.

As much of the plot revolves around games of golf, many futuristic innovations appear on the green. Self-propelled mechanized caddies transport clubs, specialized golfing jackets automatically proclaim “Fore!” on swings, and the golf clubs themselves keep score. McCullough even predicted the development and success of televised sports, though again accomplished by mirrors and generally viewed in theaters.

The year 2000 was also remarkably progressive in a roundabout away. Women are treated exactly the same as men, with such similar dress that it is difficult to distinguish between the sexes on the street. Most lawyers, ministers, doctors, and politicians are women, as well as all clerks. This development is not entirely equitable, as one character explains: “All we men have got to do is to play golf, while the women do all the work.”

The world is rather more peaceful, thanks to the development of a kind of exploding gas that renders everyone within a 16-kilometers (10 mi) radius unconsciousness for two days. As the technology made open warfare a rather impractical affair, the leaders of the year 2000 resolve geopolitical differences in a far more civilized fashion—golf tournaments.

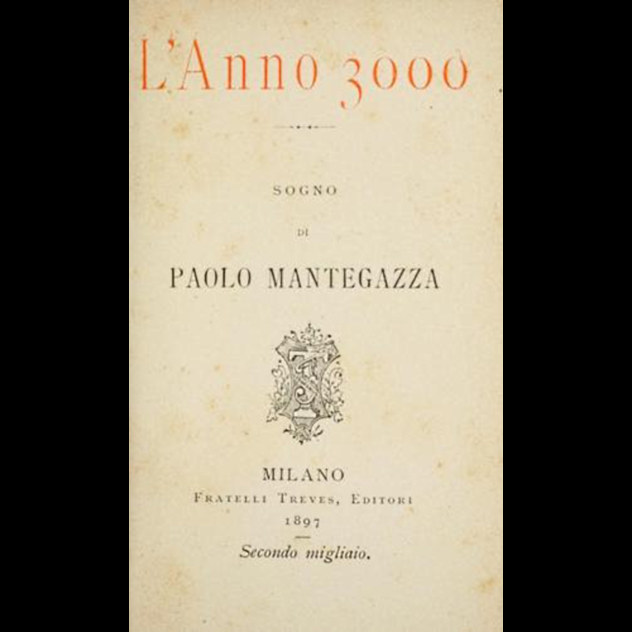

1 L’anno 3000

In 1897, Italian physician and anthropologist Paolo Mantegazza wrote L’anno 3000, translated into English as The Year 3000: A Dream. The book tells the story of Paolo and Maria, a young couple traveling from Rome to Andropolis, capitol of the United Planetary States located somewhere in the Himalayas, in order to obtain a marriage license and permission to “transmit life to future generations.”

Mantegazza’s work seems particularly interesting for its somewhat accurate predictions of future technologies, including CAT scans, aerial flight, credit cards, prefabricated homes, synthetic foods and drugs, and artificial intelligence. Movie theaters exist in the form of the panopticon. The development of 4-D multisensor cinema is presaged in the form of a device called the aesthesiometer, which is installed in theater seats and provides varying levels of visual, auditory, and olfactory sensation.

Meanwhile, the history of the future includes catastrophic war and European federation, presaging the World Wars and the formation of the European Union. The citizens of the far future speak a common cosmic tongue and have a single, bureaucracy-free government. They enjoy long lives, reasonable working hours, universal suffrage, and the right to divorce. Mental illness has been nearly eradicated, and crime has dropped to levels so low that the judiciary and police force has been disbanded.

One memorable scene has the young couple visiting a natural history museum and viewing an exhibit on “possible people,” meaning scientific speculations of extraterrestrial life. Paolo’s objections seem to predict later arguments in the science fiction community over anthropomorphism of aliens:

Oh, my dear Maria, how comical these planetary angels are, how grotesque, above all, how impossible! [ . . . ] We can imagine only anthropomorphic forms, and so, just as the ancient founders of theogonies could fashion their gods only by clothing them in human skin, so these odd creators of supermen were unable to go beyond the human and the animal world.

In the year 2525, if David Tormsen is still alive, you may find him at [email protected].