History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

Top 10 Fascinating Insect Impostors

Many insects have look-alikes, or impostors. Most of these look-alikes are other bugs. Some of these pretenders resemble disease-carrying insects or insects that are harmful to property, so it’s good to be able to tell the difference between the real deal and the deceiver. In most cases, careful attention to appearance and behavior are enough to allow even those of us who aren’t entomologists, or bug doctors, to recognize the true insect from its impostor.

10 Bedbug Impostors

While it’s true that more and more beds are infested with bugs, this increase may seem even greater than it actually is thanks to bedbug impostors—insects that look like but are not really bedbugs. The fact that quite a few insects resemble bedbugs enough to be mistaken for them can exaggerate the extent of true infestations. By learning the difference between actual bedbugs and bedbug impostors, we can keep from bugging out should one of the impostors become a temporary bedfellow.

Due to their similar appearances or behaviors, bat bugs, newborn cockroaches (pictured above), wood ticks, carpet beetles, spider beetles, and fleas have all been mistaken for bedbugs. Although bat bugs feed on bat blood, these bloodsuckers will seek other prey—including us—when bats are unavailable.

They look quite a bit like bedbugs, too, so they make good impostors. Unlike bedbugs, though, bat bugs hang out near bat roosts. The fringe hairs below their heads are also longer than those of bedbugs.

Cockroaches look much different than bedbugs when they are older, but recently hatched roaches, not so much, which is why they’re sometimes mistaken for bedbugs.

The differences between ticks and the bedbugs for which they’re sometimes mistaken? Ticks live outdoors, bedbugs indoors. Ticks attach themselves to one spot, feeding there exclusively. Bedbugs are more nomadic, traveling over the body to sample the fare at many locations.

Carpet beetles feed on fabric, not people, and, although shaped like bedbugs, they aren’t flat. Bedbugs are. However, among other tasty tidbits, these insect impostors enjoy “our dead skin,” an appetite that leads them to hang out “in and around our mattresses.” That’s why we sometimes take them for bedbugs.

Spider beetles aren’t flat, either, but their color is close to that of adult bedbugs, and both insects hide in cracks and are active at night.

Like bedbugs, fleas often live in carpets, bite, and suck blood, often while they are in bed with their human hosts or hostesses. In carpets, fleas remain “in an undeveloped state” for six months or longer until they’re activated by “direct pressure, carbon dioxide, and/or heat” and “progress to their adult stage.” Because their behavior is similar to that of bedbugs, they’re sometimes mistaken for them.

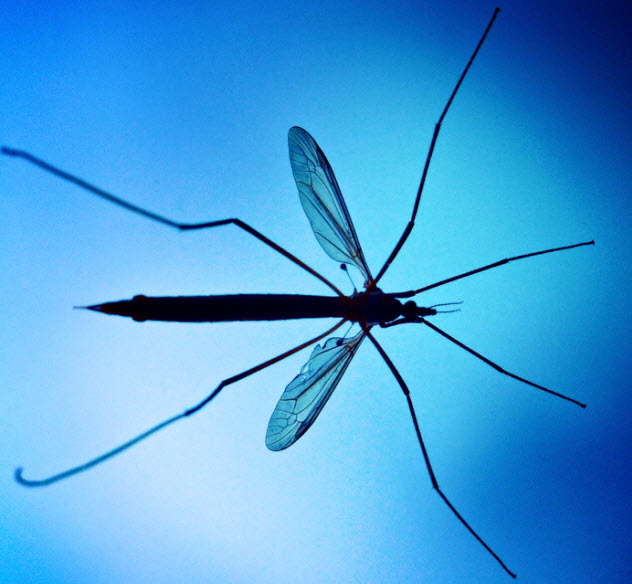

9 Mosquito Impostors

Midges, crane flies (pictured above), and fungus gnats are sometimes confused with mosquitoes.

Mosquito bites are unpleasant. They can also transmit dengue, encephalitis, filariasis, malaria, the West Nile virus, and yellow fever. For these reasons, we’re justifiably concerned about being bitten by them. However, there’s no need for humans to fear most mosquito impostors. (Only female mosquitoes suck blood, by the way. Males eat only honeydew, flower nectar, and plant juices.) The trick, of course, is telling one from the other.

Fortunately, it’s pretty easy to distinguish between mosquitoes and mosquito impostors. Mosquitoes bite. Most mosquito impostors don’t. However, midges do bite. Unlike mosquitoes, they don’t pierce the skin as a needle would. Instead, they cut it as a pair of scissors does and then lick the resulting pool of blood from the skin. Only females bite as male midges have weak jaws and instead feed on “rotting plants” and flower nectar.

Mosquitoes can also transmit disease to humans. Impostors can’t. But fungus gnats do sometimes transmit diseases to plants, and midges can infect animals with the bluetongue virus.

8 Tick Impostors

Just as ticks are sometimes mistaken for bedbugs, billbugs (pictured above) are often mistaken for ticks. It is important to know the difference because ticks carry Lyme disease. Billbugs don’t.

How to tell the difference? The bugs do look alike, but the key is to judge them by their actions, not their looks. Ticks suck blood, and, over a period of days, they swell, becoming larger. Ticks are loners, but billbugs like to hang out together in swarms. Ticks feed on people and animals. Billbugs eat grass.

7 Cockroach Impostor

It may not do much for their self-esteem (if bugs have self-esteem), but water bugs are often mistaken for cockroaches.

Appearances can be deceiving, especially since one does look like the other. The key is the insects’ behavior rather than their appearance. While cockroaches like water, they aren’t aquatic as water bugs are.

Cockroaches are scavengers. Not so cockroach impostors. Water bugs hunt down and kill their prey, such as mosquitoes. For the giant water bug (pictured above), which grows to 10 centimeters (4 in), “crustaceans, tadpoles, salamanders, fish, and amphibians” are also on the menu. These giants can eat prey “50 times” their own its size.

While it is true that both cockroaches and water bugs will hide, water bugs are more likely to play dead than to run. Also, unlike cockroaches, water bugs will bite. They have a particularly nasty bite, too, injecting “digestive enzymes” and extracting “liquefied tissue.”

Only some cockroaches can fly, but all water bugs can. Finally, the insects differ in their sociability. Cockroaches like to hang out with one another, but water bugs are lone wolves (so to speak).

6 Triatomine Bug Impostor

Unless we’re entomologists or we know one, it’s unlikely that we’re familiar with triatomine bugs. Basically, they’re bloodsuckers. Their habitat? Mostly the southern United States and Latin America. They tend to live around houses and transmit the parasite that causes Chagas’ disease, an incurable illness that damages the heart and intestines. Fortunately, although the disease is incurable, measures can be taken to prevent infection.

The wheel bug (pictured above) is also sometimes mistaken for the triatomine bug. Although the wheel bug preys on other insects, it will bite people, too, and its bite is quite painful. Its saliva contains a venom, which it injects into its victim through a tube in its beak. The venomous saliva digests its prey, and the wheel bug sucks the digested juices into its stomach through a second tube in its beak.

5 Brown Marmorated Stinkbug Impostors

The squash bug (pictured above) and several others of its own kind resemble the brown marmorated stinkbug closely enough to be confused with it. However, many features of the brown marmorated stinkbug differentiate it from other stinkbugs.

It is distinguished from similar stinkbugs by its pair of “wide, light-colored, banded areas on the antennae,” by an abdomen extending “past the wings” so that “light-colored triangles” are visible “past the wing edges,” and by the presence of “only one small tooth along each leading edge of the thorax . . . just behind the eye.” In addition, “when disturbed,” the brown marmorated stinkbug exudes an odor resembling that of coriander.

Although the squash bug is sometimes mistaken for the brown marmorated stinkbug, the squash bug’s body is long whereas the brown marmorated stinkbug’s body is round-looking. The Western conifer seed bug looks somewhat like the squash bug and could, therefore, also be confused with the brown marmorated stinkbug. However, the squash bug differs slightly in color and has “expanded tarsi [leg segments] on its hind legs.”

Various brown stinkbugs, which are also sometimes confused with brown marmorated stinkbugs, differ in their coloration and in other characteristics. Some are smaller and have dark hind segments. In addition, half their antennae are dark, and they don’t enter houses as the brown marmorated stinkbug does.

Stinkbugs of the Brochymena species are close to the same size as the brown marmorated stinkbug, but the antennae of these impostors may be marked with lighter spots rather than the darker bands of the brown marmorated stinkbug’s antennae. However, what most clearly differentiates the two is the presence on the Brochymena species of “pronounced teeth along the leading edge of the thorax behind the head and just ahead of their shoulders.’ ”

Two other stinkbugs commonly mistaken for the brown marmorated stinkbug are the Menecles insertus (which lacks a common name) and the spined soldier bug. The former is smaller, though, and lacks the brown marmorated stinkbug’s distinctive “light-colored” antennae banding.

There are anatomical differences, too, and another color variation. The Menecles insertus‘ thorax is “more rounded,” and it does not have the “marbled brown” color of the brown marmorated stinkbug. The spined soldier bug is smaller than the brown marmorated stinkbug. It lacks the light bands on its antennae, although it shares the brown marmorated stinkbug’s “marbled brown” color. It also has a dark brown spot on “the membranous part of the front wings” when they “overlap.”

4 Periodical Cicada Impostor

In science, there’s a name for almost everything. Periodical cicadas are no exception. They’re called “periodical” because, unlike most of their kind, nearly all of them in the same area mature during the same year. They also live underground for years at a time, sucking tree juices from roots, whereas annual cicadas “surface each summer.”

Periodical cicadas aren’t locusts (pictured above), although they are frequently confused with them. For one thing, periodical cicadas don’t bite, and they don’t devour acres of crops. In addition, periodical cicadas actually benefit both man’s best friend and wild animals.

Dogs, attracted by the insects’ buzzing, like to chase them, and a number of other animals—“turkeys, raccoons, skunks, and coyotes” included—like to eat them. More significantly, periodical cicadas are cousins of leafhoppers, aphids, and scale insects whereas locusts are a kind of grasshopper.

Equipped with abdominal tymbals (membranes), periodical cicadas produce a buzzing sound like others of their kind. Lacking tymbals, locusts do make these sounds. Locusts swarm. Periodical and other cicadas may swarm, but they often do not.

Cicadas’ eyes are bigger than those of locusts. Cicadas’ “forewings . . . extend beyond the abdomen.” Locusts’ forewings don’t. There is a much larger variety of cicadas than of locusts. Finally, despite turkeys, raccoons, skunks, and coyotes, periodical and other cicadas live much longer than locusts.

3 Common Chinch Bug Impostors

It is not surprising that false chinch bugs are mistaken for the common chinch bug. The two look quite a bit alike, and their habits are similar. However, the insects have different appetites. The false chinch bugs are fond of dining upon sorghum and weed seeds. The common chinch bug prefers a greater variety—a smorgasbord of “corn, rice, small grains, sorghum and bunch grasses and turf grasses.”

2 Bumblebee Impostors

Big, black-and-yellow carpenter bees (pictured above) are often confused with bumblebees. However, the impostors’ shiny black tail section distinguishes them. The males cannot sting. The females can but seldom do unless they’re trapped.

Once again, both appearance and behavior help to differentiate the carpenter bee from the bumblebee. Bumblebees are hairy. Carpenter bees are almost bald. Bumblebees live underground. Carpenter bees dwell under the eaves of houses or in trees.

Bumblebees like to socialize. Carpenter bees are loners. Unlike bumblebees, carpenter bees also drill into wood, creating tunnels through “doors, windowsills, roof eaves, shingles, railings, telephone poles, and sometimes even wooden lawn furniture.” They also stain such items with their excrement.

Over time, generations of the carpenter bees can do considerable damage to property. If carpenter bees are present, they are likely to cause problems, but bumblebees, typically, do not. Fortunately, a licensed exterminator can get rid of carpenter bees using insecticidal sprays and dusts.

1 Sphinx or Hawk Moth Impostor

The sphinx or hawk moth also has an impostor. However, this pretender isn’t another insect. It’s a bird! A hummingbird (pictured above), to be exact.

Like the hummingbird, this gigantic moth hovers over flowers and dips its lengthy proboscis into blossoms to extract nectar. Its rapid wing beats even make a humming sound, so it is sometimes referred to as a “hummingbird moth.”

It is one of only four “nectar feeders” in existence. The others are hummingbirds (for which it is sometimes mistaken), some species of bats, and hoverflies. Fortunately for homeowners, the hummingbird moth is not harmful to plants.

Gary Pullman, author of the urban fantasy novel A Whole World Full of Hurt, which is soon to be published by The Wild Rose Press, lives south of Area 51, which explains a lot, especially his interest in the anomalous and the bizarre. An English instructor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Gary publishes instructional essays about composition on his website, Essays Made Easy.