Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

10 Deliberate Historical Errors and Misrepresentations

Deliberate errors and misrepresentations occur in a variety of fields of human endeavor. The motives for such mistakes and misrepresentations vary. Some purposes are reasonable, a few are amusing, several are nefarious, and a couple are downright bizarre. These deliberate errors and misrepresentations share a common element, though: All of them are intriguing.

10 Rand McNally’s Cartographic Errors

Customers rely on road atlases and other maps to find their way, especially when they’re traveling. Accuracy, therefore, is critically important, both to the drivers who depend on their maps and to the mapmakers who create them. Or is it? Not always, it seems.

In a practice dating back to the 1800s, maps often include deliberate mistakes, inserting imaginary streets, called “trap streets” in the trade. These nonexistent streets help mapmakers detect plagiarism when others illegally copy their maps, a problem that has long plagued the business. Mapmakers invest a great deal of time, effort, and money in mapping urban, suburban, and rural areas of the country, often on a national or even international level. Therefore, plagiarized rip-offs of their work are as expensive as they are vexing. Fake streets help cartographers catch plagiarists red-handed, so to speak.

For example, Rand McNally used trap streets until the 1980s. like the fictitious “La Taza Drive” in Upland, California. An entire nonexistent street isn’t always incorporated into a map; there are other ways to trap plagiarists. For example, An existing street can be misrepresented, too, such as by adding curves that aren’t there or making a busy road look like a narrow alley.

The inclusion of fictional towns, or “paper towns,” as they’re also known, is another way of trapping plagiarists. According to Rebecca Maxwell of GIS Lounge, both Rand McNally and Google have fallen for this trick:

In the 1930s mapmaker Otto Lindberg and his assistant Ernest Alpers fashioned a phony town called Agloe in upstate New York. No such town existed, yet a few years later, Rand McNally released their own map of New York with Agloe on it. Similarly, a fake English town called Argleton appeared on Google Maps up until 2009. Google stated that this was the result of human error but the town can be found in print forms of maps from Tele Atlas.

Such traps may have become a thing of the past. In the digital age, with several companies offering free maps online, not only are fewer maps and road atlases selling, but the rulings concerning what does and does not constitute cartographic copyright violations are problematic, to say the least: In Feist v. Rural Telephone Company, the US Supreme Court ruled that map data is not intellectual property and can’t be copyrighted. Perhaps motorists need no longer worry about unexpectedly ending up on Upland’s La Taza Drive or making a wrong turn and finding themselves in Agloe.

9 The New Columbia Encyclopedia‘s Fake Article

We can’t even trust encyclopedias.

The 1975 edition of the New Columbia Encyclopedia contains a deliberate error—an entire article concerning Lillian Virginia Mountweazel, an alleged photographer from Bangs, Ohio. According to the article, Mountweazel, who lived from 1942 to 1973, “produced [ . . . ] celebrated portraits of the South Sierra Miwok in 1964.” The government allegedly thought so well of her work that it awarded her “grants to make a series of photo-essays of unusual subject matter, including New York City buses, the cemeteries of Paris, and rural American mailboxes.” Ironically, the fake photographer died young, at the age of 31, “in an explosion while on assignment for Combustibles magazine.” Before her untimely demise, however, she saw her work displayed “extensively abroad and published as Flags Up! (1972).”

She was quite an accomplished woman, especially since she never existed. She was a “copyright trap,” designed to catch violators who illegally copied the encyclopedia’s content “without due attribution or royalties.”

8 Royal Mail’s PostZon Database

The United Kingdom’s Royal Mail, a privatized company, has 1.8 million postcodes in PostZon, which is a database in “comma-separated variable form.” A copy of the database was leaked by Wikileaks. The copy included the longitude and latitude of each of the company’s postcodes.

The leaked database copy could be a gold mine for advertisers or others who want access to the postcodes. However, this does not seem to be the case. It seems that people fear the database may contain deliberate mistakes that Royal Mail could use to not only “identify unlicensed use,” but also to prove that “the data was copied rather than created from scratch.” The company refused to affirm or deny whether the database does, in fact, include such deliberate errors. The simple possibility that the database could contain them seems enough, however, to have discouraged potential data thieves.

7 Gilbert Stuart’s Portrait Of George Washington

George Washington hangs in the East Room of the White House. No, not Washington himself but rather a portrait of him. Specifically, a copy of a portrait of him, to be exact . . . or one of several copies. The original, commissioned by Senator William Bingham and painted by Gilbert Stuart, occupies a place of honor in the Smithsonian Institute’s National Portrait Gallery. Stuart also painted the copies. The paintings, original and copies alike, show Washington refusing a third term as president.

The White House copy (and the others) contains a spelling error, but it’s not because Stuart couldn’t spell well. The error is deliberate and has a purpose. It occurs in the spelling of the last word in the title of one of the books displayed in the lower left corner of the portrait—Constitution and Laws of the United Sates. Its purpose? To distinguish it from the original painting. The other copies also bear Staurt’s deliberate error for the same reason.

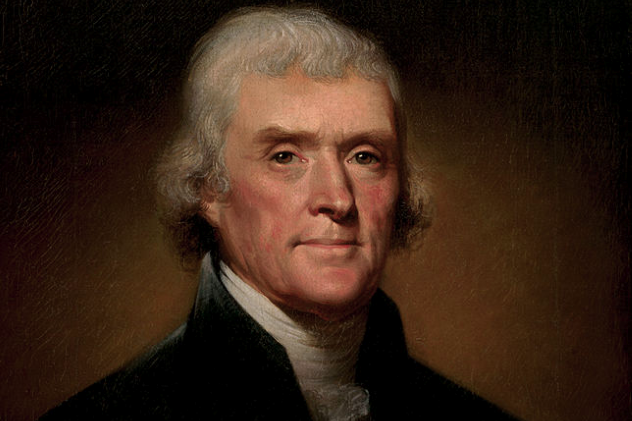

6 The Jefferson Memorial

Besides having been a US president and the author of The Declaration of Independence (to name but two of his more famous accomplishments), Thomas Jefferson, one of his country’s founders, was also a “civic humanist,” distrustful of the ways of commerce, a “proto-socialist,” suspicious of industry and opposed to capitalism, and a man who took sides in a host of other political, economic, and social issues. That’s what the advocates and supporters of such causes would have had others believe, at least. Because of his historical importance and accomplishments, Jefferson has been held up frequently as an example of one who endorsed just about any cause, whether Jefferson himself was ever an advocate of it or not.

For political purposes, even the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, DC, plays a bit fast and loose with the founder’s actual words. Inscriptions on the interior walls of the memorial sometimes include words that he never said. Other times, truncated quotations present his words out of context. Ronald Hamowy, professor emeritus of intellectual history at the University of Alberta, regards these corruptions of Jefferson’s views as “perhaps the most egregious examples of invoking Jefferson for purely transient political purposes.”

Planned and built during the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the memorial’s inscriptions suggest that Jefferson advocated positions consistent with the aims of the New Deal—with which, some scholars contend, Jefferson would in fact have had little sympathy. Not only is Jefferson made to appear to have “sympathized” with the New Deal that President Roosevelt was so eager to promote, but Jefferson’s belief in the value of ensuring that voters are “educated so that liberty might be preserved” were twisted into an endorsement of universal public education.

5 Thomas Jefferson’s Letter To Philip Mazzei

Speaking of Jefferson, as vice president, he made the mistake of writing a letter to a former neighbor, Philip Mazzei, who had moved to Pisa, Italy. The letter, sent, on April 24, 1796, from Monticello in Virginia was personal. Essentially, he was bringing Mazzei up-to-date on business matters and friends. Paragraphs that Jefferson had written—but not in his letter to Mazzei—made the rest of their author’s life a living Hell.

Mazzei betrayed Jefferson’s confidence by copying the letter and giving it to three of his friends, Giovanni Fabbroni, Jacob Van Staphorst, Giovanni Lorenzo Ferri de Saint-Constant, all of whom Mazzei was cultivating for business or personal reasons. When Jefferson’s letter was translated into French and published on January 25, 1797, in Paris’s Gazette Nationale ou Le Moniteur Universel, it contained four additional paragraphs criticizing the Federalists. Written earlier, on another occasion, those paragraphs were never in Jefferson’s original letter, but they were added, without explanation, as if they were.

The later publication of the altered letter in US newspapers created a firestorm. Editor Noah Webster obtained a copy from a French newspaper, of which he made a copy in English and published in the May 2, 1797, issue of his newspaper, Minerva. By this point, the letter had been translated from English into French and then back again into English.

Jefferson explained to James Madison that he could not wholly deny authorship of the letter, because most of it was his, the added paragraphs notwithstanding. However, he pointed out that the French translation of his letter contained an error. Where he’d written “forms,” the translation had read “form,” a seemingly simple error, but one which, he said, substantially misrepresented the significance of his statements. In addition, Jefferson believed that the letter had gone through yet another translation, into Italian, along the way. It had been translated from English into Italian (the language in which Mazzei wrote), from Italian into French, and, finally, from French back into English, implying, perhaps, that, each time, there would have been a chance for further corruptions of his original views. (Jefferson seems to have been wrong in his conjecture that his letter was ever translated into Italian.)

Federalists interpreted Jefferson’s letter as “a thinly disguised attack on George Washington,” the nation’s beloved first president. They made much use of the letter to advance their own cause, often at Jefferson’s expense. For example, the French translation of Jefferson’s letter contained inaccuracies and errors, which were left to stand without correction or explanation, and its “unauthorized publication” frequently appeared “out of context.”

Once again, a deliberate mistake was made to serve political interests. However, Jefferson was later elected president, and he never severed his friendship with Mazzei, the man who caused him so much trouble.

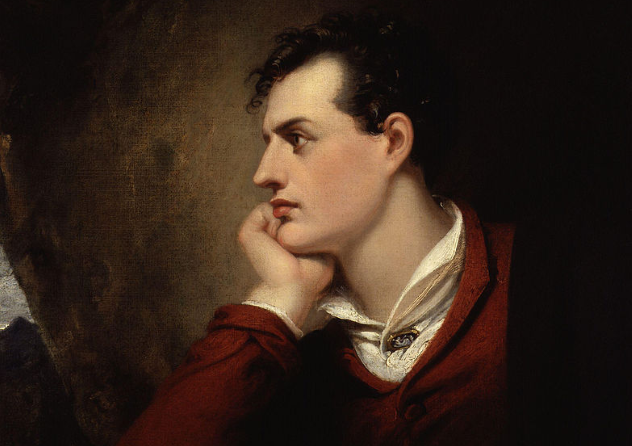

4 The Letters And Journals Of Lord Byron

English nobleman and poet George Gordon Byron, more commonly known as Lord Byron (a baron), wrote enough personal letters and journal entries to fill a dozen volumes. His writings chronicle an eventful life from his early childhood onward. They portray him as not only a man of letters, but also as an international traveler, a correspondent with fellow poets and other celebrities of his day, a ladies’ man, a grieving father, a wit, and a man interested in political revolution. His correspondents included some of the most accomplished writers of his day—Sir Thomas Moore, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Leigh Hunt, Matthew Lewis, and Mary Shelley. It seems curious, then, that this great Romantic poet found himself vexed by the seeming chaos of punctuation.

G. Thomas Tanselle concludes that Lord Byron’s punctuation “follows no rules of his own or others’ making. He used dashes and commas freely, but for no apparent reason, other than possibly for natural pause between phrases, or sometimes for emphasis. He is guilty of the ‘comma splice,’ and one can seldom be sure where he intended to end a sentence, or whether he recognized the sentence as a unit of expression.” The poet himself knew that he had trouble with punctuation: “Byron himself recognized his lack of knowledge of the logic or the rules of punctuation,” Tanselle observes. Nevertheless, he was obviously content to leave the errors in place rather than have someone correct them, so they are deliberate.

His difficulty with punctuation caused the editors of his volumes of personal correspondence and journal entries a problem of their own—how to bring order out of the chaos of Byron’s writing without destroying the essence of his style and the passion of his words. They seemed to agree that something must be done. Otherwise, much of Byron’s writing might seem virtually incomprehensible to the public. “It is not without reason then that most editors, including R. E. Prothero, have imposed sentences and paragraphs on him in line with their interpretation of his intended meaning,” Tanselle concedes.

However, their imposition of “sentences and paragraphs” on his writing, based on their own “interpretation of his intended meaning,” may have created a worse problem: Their interpretative editing, Tanselle believes, may actually detract “from the impression of Byronic spontaneity and the onrush of ideas in his letters, without a compensating gain in clarity.” In addition, editorial meddling “may often arbitrarily impose a meaning or an emphasis not intended by the writer.” In this case, by cleaning up and fixing Byron’s prose, his editors may have done the poet a great disservice. It might have been better to have left some deliberate mistakes uncorrected.

3 Hitler’s Horoscope

Adolf Hitler was a superstitious man. He depended on his astrologer’s advice and often made even major decisions based on interpretations of his horoscope. British intelligence saw his reliance on the zodiac as a potential weakness that could be exploited.

Louis de Wohl, a Jew who had fled Nazi Germany, sought to convince British authorities to use Hitler’s horoscope against him. Hired by Sir Charles Hambro, the head of Britain’s Special Operations Executive, de Wohl was installed in a hotel suite on London’s Park Lane, where, consulting the stars, he wrote “vague” horoscopes for Hitler and other Nazi leaders, which, according to the letterhead of the paper, originated from the “Psychological Research Bureau.”

During a trip to the United States, he was given the task of countering German astrologers’ readings. Calling himself “The Modern Nostradamus” after the famous (some would say infamous) French seer, de Wohl suggested that times his German colleagues had designated as favorable for Hitler’s plans were, in fact, potentially disastrous. Instead of winning, de Wohl insisted, the stars indicated that Hitler would lose.

When his “services were no longer needed,” de Wohl was “called home,” and upon his return to London, he found that his “hotel apartment [had been] stripped bare and his ‘department’ disbanded.” Although intelligence officers debated on how best to “dispose” of him, they opted “to keep him happy and continue to employ him,” deciding that “de Wohl was potentially damaging the reputation of his employers.” After all, de Wohl’s intentionally false horoscopes had aided them in the war effort, intensifying Hitler’s insecurities and anxieties.

2 Scriptural Errors

In translating the New Testament from Greek parchments, translators sometimes made deliberate mistakes for a variety of reasons, changing spellings, censoring vulgarity, and correcting grammar. For example, the Gospel According to Mark was originally quite vulgar. Scribes adjusted his language as needed.

Other deliberate mistakes were made to “harmonize” Old Testament quotations with “Gospel parallels” and “common expressions.” In other words, scribes would slightly change one speaker’s dialogue to bring it into absolute agreement with another Biblical figure’s speech on the same topic. If one book read “eat and drink,” but a later book, repeating or commenting on the previous verse, only said “eat,” a scribe might change the reference to also read “eat and drink.” Scribes also took it upon themselves, at times, to correct embarrassing discrepancies. In one case, several prophets were referenced by a scripture, but Mark 1:2–3 spoke of only Isaiah. Scribes changed “Isaiah” to “prophets.”

The Byz manuscript, upon which the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible is based, combines two readings into one new reading. Whereas, in Luke 24:53, one earlier manuscript might have used the words “blessing God,” and another might have read “pleasing God,” the KJV scribes used both: “They were continually in the temple blessing and praising God.”

Other such deliberate mistakes originated when scribes made “doctrinally motivated changes” or added “enriching material.”

1 King Tut’s Privates

Not all deliberate mistakes or misrepresentations are printed, digitized, inscribed, or handwritten. King Tutankhamun’s private parts certainly weren’t.

The boy pharaoh was “entombed in an unusual way,” without his heart and with his penis “mummified erect” at a 90-degree angle. Equally bizarre, his remains and the coffins containing them were covered in a thick layer of black liquid, which may have resulted in Tut catching fire.

Why on Earth was King Tut buried in such a peculiar fashion? Not surprisingly, these anomalies have caught the eye of both scholars and the media. The American University in Cairo’s Egyptologist, Salima Ikram, thinks he knows, and he sets forth his hypothesis in a new paper in the journal Études et Travaux.

King Tut’s erection and the black liquid covering him and his coffins are deliberate, not accidental, effects of his embalming, designed to create the impression that he is none other than Osiris, god of the underworld. King Tut’s virile manhood, as evident in his erection, suggests the god’s own fertility, and the black liquid recalls Osiris’s pigmentation. The absence of the pharaoh’s heart alludes to Osiris having been dismembered by his brother Seth. Like Osiris, King Tut’s heart was buried separately from the rest of him.

Gary Pullman lives south of Area 51, which, according to his family and friends, explains “a lot.” His 2016 urban fantasy novel A Whole World Full of Hurt, will be published by The Wild Rose Press. An instructor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, he writes several blogs, one of which is bit Lit: Short Stories Anesthetized, Euthanized, and Sterilized at http://murdertodissect.blogspot.com/